Brixton Letter 1

BR to Governor of Brixton Prison / Carleton Haynes

May 2, 1918

- ALS

- National Archives, UK

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila TurconCite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, russell-letters.mcmaster.ca

/brixton-letter-1Papers 14: App. XIII.1

BRACERS 57173

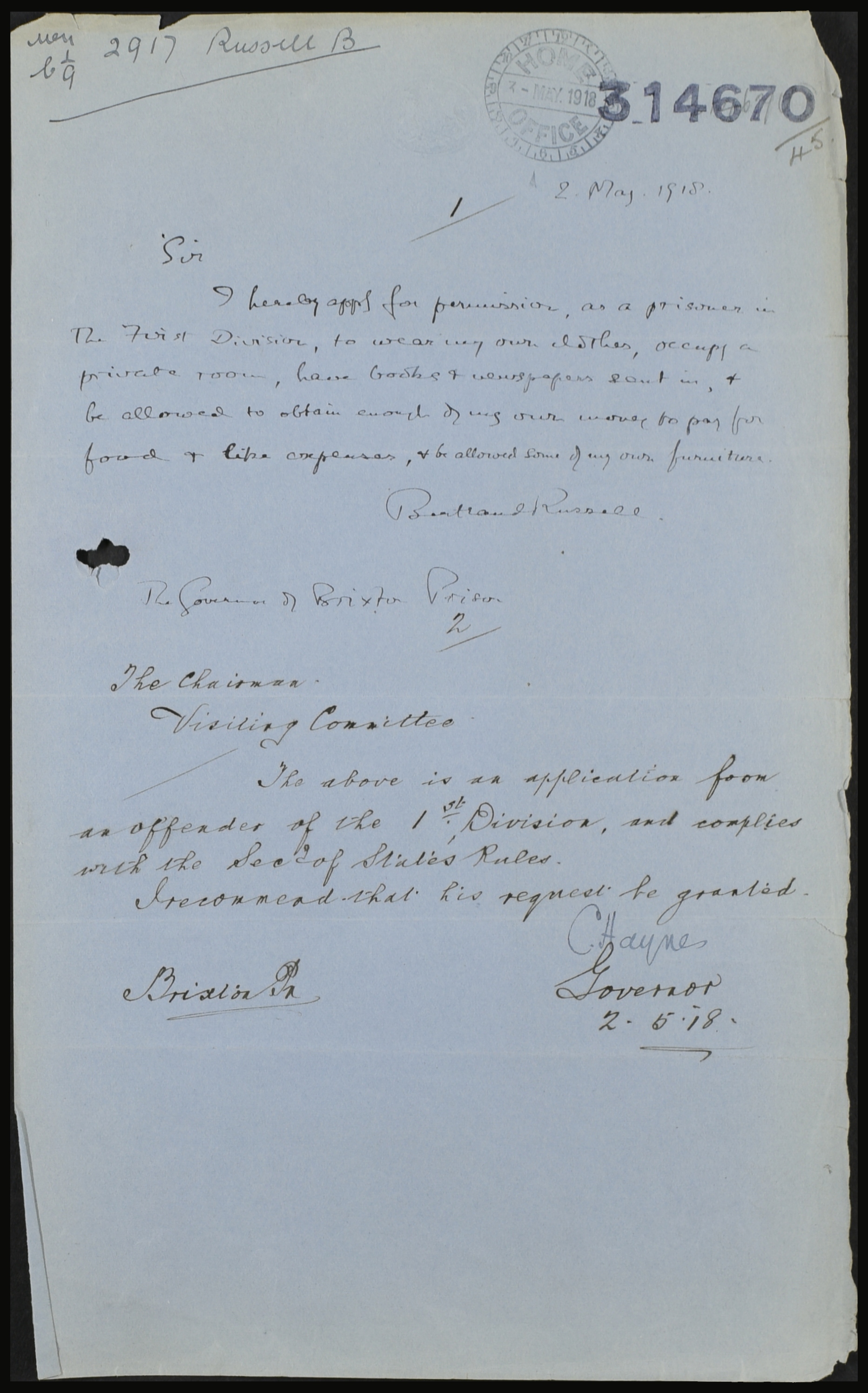

<Brixton Prison>1

2. May. 1918.2

The Governor of Brixton Prison

Sir

I hereby apply for permission, as a prisoner in the First Division, to wear my own clothes, occupy a private room,3 have books and newspapers sent in, and be allowed to obtain enough of my own money to pay for food4 and like expenses, and be allowed some of my own furniture.a

Bertrand Russell.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from a digital scan of BR’s signed, handwritten original in the National Archives, UK. Prisoners’ correspondence was subject to the governor’s approval, or that of his deputy. This letter has the signature of C. Haynes (the governor) to an evidently dictated, handwritten letter of the same date, below BR’s letter on the same blue sheet, recommending that his request be granted since it “complies with the Secretary of State’s Rules.” The letter was published as App. XIII.1 in Papers 14.

- 2

[date] This was the second day of BR’s imprisonment. On 1 May 1918 he lost the appeal of his 9 February conviction under the Defence of the Realm Act for making statements in The Tribunal “intended or likely … to prejudice His Majesty’s relations with foreign powers” (see also “Mr. Bertrand Russell’s Appeal; Mitigation of Sentence”, The Times, 2 May 1918, p. 2). All that BR publicly recalled of his first day in Brixton was that the warder at the gate asked his religion and then how to spell “agnostic” (Auto. 2: 34).

- 3

private room How soon BR stopped sharing a cell (the request for privacy strongly suggests he shared one the first day or days) can’t be determined. As for the cost of this privilege, Alan Wood, who was frequently in touch with BR during the writing of Bertrand Russell, the Passionate Sceptic (London: Allen & Unwin, 1957), stated that “Russell had a cell larger than usual, for which he had to pay a rent of 2s 6d a week” (p. 113).

- 4

food When BR recalled his first-division privileges many years later, food stood out: “You had no prison labour to do, you were allowed your own clothes, you were allowed your own food. And mind you, at a time when everybody else was rationed, I alone was not. Why? Because they hadn’t thought of extending rationing to this very tiny group of first-division prisoners” (Speaking Personally, John Chandos, interviewer [London: Pye-Plus Nonesuch Records, 1961], side 1, 31: 43).

Textual Notes

- a

and be allowed … furniture The clause was squeezed in as an afterthought (see the letter image).

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

First Division

As part of a major reform of the English penal system, the Prison Act (1898) had created three distinct categories of confinement for offenders sentenced to two years or less (without hard labour) in a “local” prison. (A separate tripartite system of classification applied to prisoners serving longer terms of penal servitude in Britain’s “convict” prisons.) For less serious crimes, the courts were to consider the “nature of the offence” and the “antecedents” of the guilty party before deciding in which division the sentence would be served. But in practice such direction was rarely given, and the overwhelming majority of offenders was therefore assigned third-division status by default and automatically subjected to the harshest (local) prison discipline (see Victor Bailey, “English Prisons, Penal Culture, and the Abatement of Imprisonment, 1895–1922”, Journal of British Studies 36 [1997]: 294). Yet prisoners in the second division, to which BR was originally sentenced, were subject to many of the same rigours and rules as those in the third. Debtors, of whom there were more than 5,000 in local prisons in 1920, constituted a special class of inmate, whose less punitive conditions of confinement were stipulated in law rather than left to the courts’ discretion.

The exceptional nature of the first-division classification that BR obtained from the unsuccessful appeal of his conviction should not be underestimated. The tiny minority of first-division inmates was exempt from performing prison work, eating prison food and wearing prison clothes. They could send and receive a letter and see visitors once a fortnight (more frequently than other inmates could do), furnish their cells, order food from outside, and hire another prisoner as a servant. As BR’s dealings with the Brixton and Home Office authorities illustrate, prison officials determined the nature and scope of these and other privileges (for some of which payment was required). “The first division offenders are the aristocrats of the prison world”, concluded the detailed inquiry of two prison reformers who had been incarcerated as conscientious objectors: “The rules affecting them have a class flavour … and are evidently intended to apply to persons of some means” (Stephen Hobhouse and A. Fenner Brockway, eds., English Prisons To-day [London: Longmans, Green, 1922], p. 221). BR’s brother described his experience in the first division at Holloway prison, where he spent three months for bigamy in 1901, in My Life and Adventures (London: Cassell, 1923), pp. 286–90. Frank Russell paid for his “lodgings”, catered meals were served by “magnificent attendants in the King’s uniform”, and visitors came three times a week. In addition, the governor spent a half-hour in conversation with him daily. At this time there were seven first-class misdemeanants, who exercised (or sat about) by themselves. Frank concluded that he had “a fairly happy time”, and “I more or less ran the prison as St. Paul did after they had got used to him.” BR’s privileges were not quite so splendid as Frank’s, but he too secured a variety of special entitlements (see Letter 5).

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).

Governor of Brixton Prison / Carleton Haynes

Captain Carleton Haynes (1858–1945), the Governor of Brixton Prison in 1918, was a retired army officer and a cousin of BR’s acquaintance, the radical lawyer and author E.S.P. Haynes. In March 1919 BR sent Haynes, in jest, a copy (now in the Russell Archives) of his newly published Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy — so that the governor’s collection of works written by inmates while under his charge would “not ... be incomplete” (BRACERS 123167).