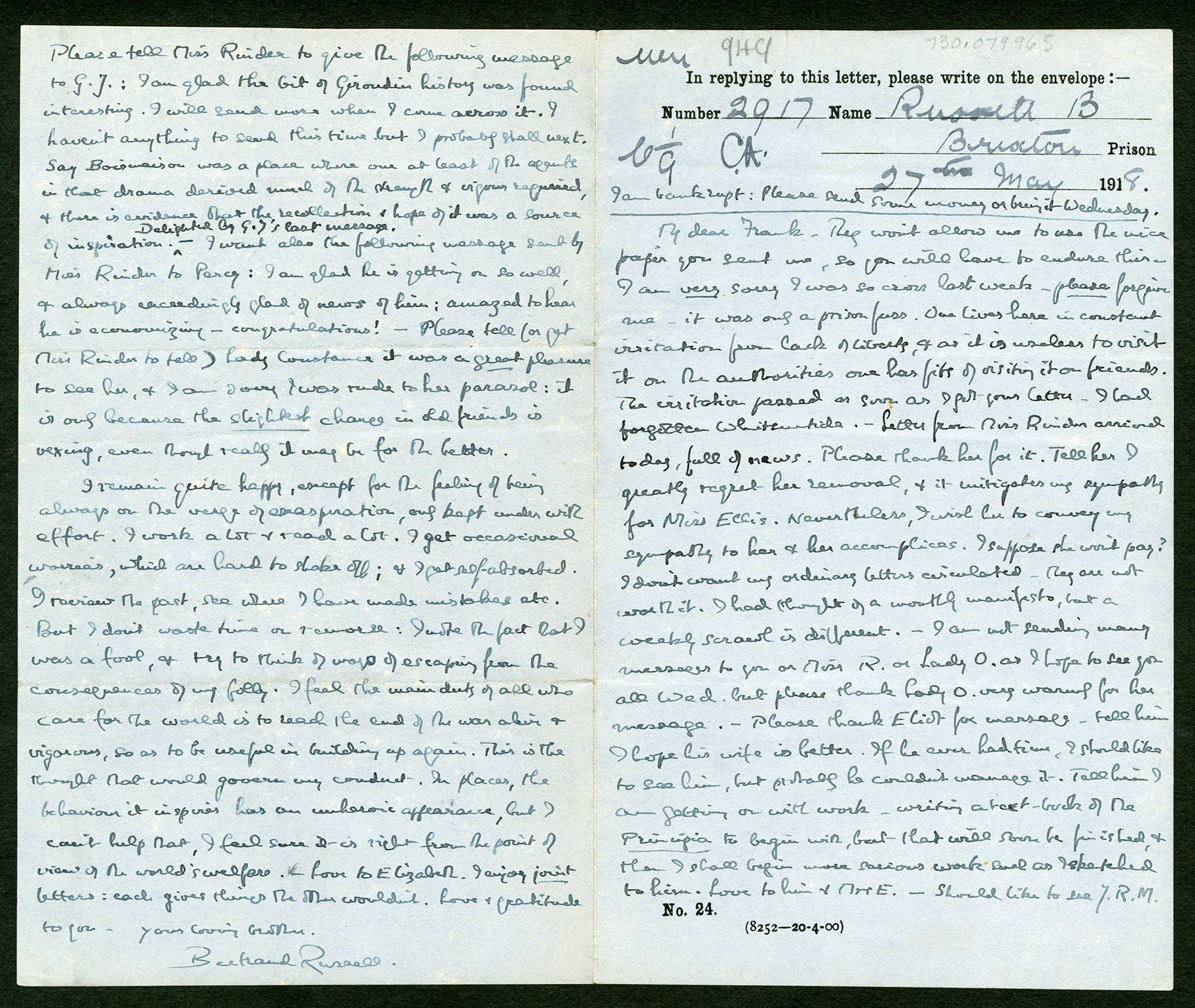

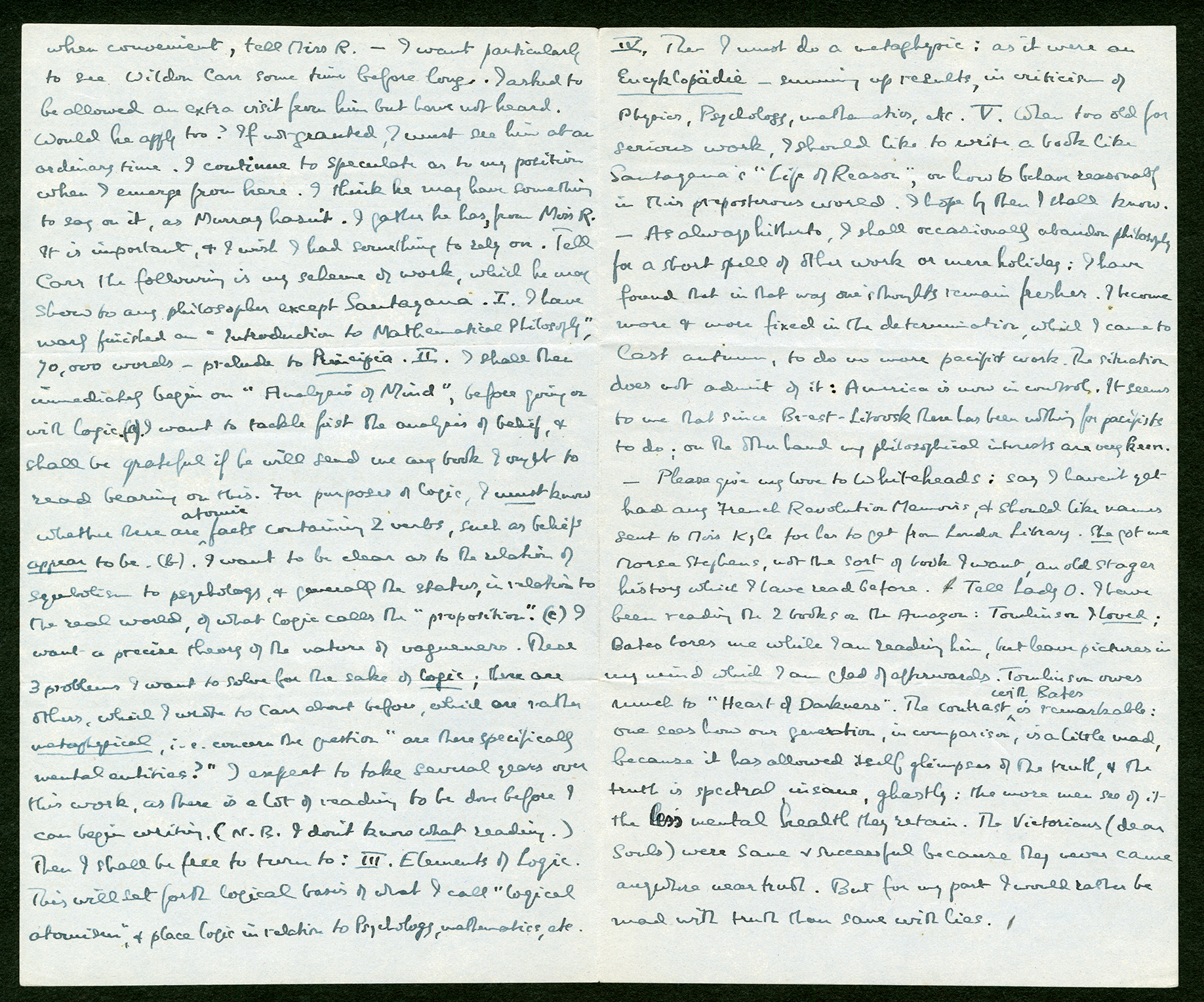

Brixton Letter 9

BR to Frank Russell

May 27, 1918

- ALS

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-9

SLBR 2: #314

BRACERS 46915

Number 2917 Name Russell B1

Brixton Prison

27th May 1918.

My dear Frank

They won’t allow me to use the nice paper2 you sent me, so you will have to endure this. I am very sorry I was so cross last week — please forgive me — it was only a prison fuss. One lives here in constant irritation from lack of liberty, and as it is useless to visit it on the authorities one has fits of visiting it on friends. The irritation passed as soon as I got your letter3 — I had forgotten Whitsuntide.4 — Letter from Miss Rinder5 arrived today, full of news. Please thank her for it. Tell her I greatly regret her removal,6 and it mitigates my sympathy for Miss Ellis. Nevertheless, I wish her to convey my sympathy to her and her accomplices. I suppose she won’t pay?7 I don’t want my ordinary letters circulated — they are not worth it. I had thought of a monthly manifesto,8 but a weekly scrawl is different. — I am not sending many messages to you or Miss R. or Lady O. as I hope to see you all Wed., but please thank Lady O. very warmly for her message.9 — Please thank Eliot for message10 — tell him I hope his wife is better.11 If he ever had time, I should like to see him, but probably he couldn’t manage it. Tell him I am getting on with work — writing a text-book of the Principia12 to begin with, but that will soon be finished, and then I shall begin more serious work such as I sketched to him. Love to him and Mrs E. — Should like to see J.R.M.13 when convenient, tell Miss R. — I want particularly to see Wildon Carr some time before long. I asked to be allowed an extra visit from him but have not heard. Would he apply too? If not granted, I must see him at an ordinary time. I continue to speculate as to my position when I emerge from here. I think he may have something to say on it, as Murray hasn’t.14 I gather he has, from Miss R. It is important, and I wish I had something to rely on. Tell Carr the following is my scheme of work, which he may show to any philosopher except Santayana.15 I. I have nearly finished an Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy, 70,000 words — prelude to Principia. II. I shall then immediately begin on Analysis of Mind,a before going on with logic. (a). I want to tackle first the analysis of belief, and shall be grateful if he will send me any book I ought to read bearing on this. For purposes of logic, I must know whether there are atomicb facts containing 2 verbs, such as beliefs appear to be.16 (b). I want to be clear as to the relation of symbolism to psychology, and generally the status, in relation to the real world, of what logic calls the “proposition”.17 (c) I want a precise theory of the nature of vagueness.18 These 3 problems I want to solve for the sake of logic; there are others, which I wrote to Carr19 about before, which are rather metaphysical, i.e. concern the question “are there specifically mental entities?” I expect to take several years over this work, as there is a lot of reading to be done before I can begin writing. (N.B. I don’t know what reading.) Then I shall be free to turn to: III. Elements of Logic. This will set forth logical basis of what I call “logical atomism”,20 and place logic in relation to Psychology, mathematics, etc. IV. Then I must do a metaphysic: as it were an Encyklopädie — summing up results, in criticism of Physics, Psychology, mathematics, etc. V. When too old for serious work, I should like to write a book like Santayana’s Life of Reason,21 on how to behave reasonably in this preposterous world. I hope by then I shall know. — As always hitherto, I shall occasionally abandon philosophy for a short spell of other work or mere holiday: I have found that in that way one’s thoughts remain fresher. I become more and more fixed in the determination, which I came to last autumn, to do no more pacifist work. The situation does not admit of it: America is now in control.22 It seems to me that since Brest-Litovsk there has been nothing for pacifists to do;23 on the other hand my philosophical interests are very keen. — Please give my love to Whiteheads:24 say I haven’t yet had any French Revolution Memoirs, and should like names sent to Miss Kyle for her to get from London Library. She got me Morse Stephens,25 not the sort of book I want, an old stager history which I have read before. — Tell Lady O. I have been reading the 2 books26 on the Amazon: Tomlinson I loved; Bates bores me while I am reading him, but leaves picturesc in my mind which I am glad of afterwards. Tomlinson owes much to Heart of Darkness.27 The contrast with Batesd is remarkable: one sees how our generation, in comparison, is a little mad, because it has allowed itself glimpses of the truth, and the truth is spectral, insane, ghastly: the more men see of it the less mental health they retain. The Victorians (dear souls) were sane and successful because they never came anywhere near truth. But for my part I would rather be mad with truth than sane with lies.e

Please tell Miss Rinder to give the following message to G.J.: I am glad the bit of Girondin history28 was found interesting. I will send more when I come across it. I haven’t anything to send this time but I probably shall next. Say Boismaison was a place where one at least of the agents in that drama derived much of the strength and vigour required, and there is evidence that the recollection and hope of it was a source of inspiration. Delighted by G.J’s last message.29, f — I want also the following message sent by Miss Rinder to Percy:30 I am glad he is getting on so well, and always exceedingly glad of news of him: amazed to hear he is economizing — congratulations!31 — Please tell (or get Miss Rinder to tell) Lady Constance it was a great pleasure to see her, and I am sorry I was rude to her parasol: it is only because the slightest change in old friends is vexing, even though really it may be for the better.

I remain quite happy, except for the feeling of being always on the verge of exasperation, only kept under with effort. I work a lot and read a lot. I get occasional worries, which are hard to shake off; and I get self-absorbed. I review the past, see where I have made mistakes etc. But I don’t waste time on remorse: I note the fact that I was a fool, and try to think of ways of escaping from the consequences of my folly. I feel the main duty of all who care for the world is to reach the end of the war alive and vigorous, so as to be useful in building up again. This is the thought that would govern my conduct. In places, the behaviour it inspires has an unheroic appearance, but I can’t help that, I feel sure it is right from the point of view of the world’s welfare.g — Love to Elizabeth. I enjoy joint letters:32 each gives things the other wouldn’t. Love and gratitude to you.

Your loving brother.

Bertrand Russell.

I am bankrupt: Please send some money or bring it Wednesday.h

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the signed original in BR’s handwriting in the Russell Archives. On the blue correspondence form of the prison system, it consists of a single sheet folded once vertically; all four sides are filled. Particulars, such as BR’s name and number, were entered in an unknown hand. Prisoners’ correspondence was subject to the approval of the governor or his deputy. This was an “official” letter, since it bears the initials “CH” of the governor, Carleton Haynes.The letter was published as #314 in Vol. 2 of BR’s Selected Letters.

- 2

nice paper you sent me BR did use some nice paper — a laid paper for the manuscript of Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy, which he had started writing some weeks before (by 21 May he had already written 20,000 words [Letter 7]). The initial paper was watermarked “EXCELSIOR | EXTRA SUPERFINE | BRITISH MAKE”. Mid-way in Ch. 7 BR switched to a laid paper that was ruled on one side and not watermarked, and he used it for the remainder of the manuscript, other manuscripts, and some smuggled correspondence. “Official” correspondence was another story. Many of BR’s first few letters to Frank Russell and Gladys Rinder were written on the prison system’s blue correspondence form, complete with a place for his prisoner number.

- 3

your letter BR must have meant Frank’s letter of 19 May 1918 (BRACERS 46914), the letter he complained in Letter 7 of not having received.

- 4

Whitsuntide The eighth Sunday after Easter. The Monday following was a British holiday until 1971, replaced by the Spring Bank Holiday. In 1918 Whitmonday was on 20 May, delaying the arrival of Frank’s letter.

- 5

Letter from Miss Rinder Dated 25 May 1918 (BRACERS 79611).

- 6

I greatly regret her removal On 25 May 1918 Gladys Rinder informed BR that his replacement as the NCF’s Acting Chairman, Dr. Alfred Salter, “wants me to take up new duties June 1st, but it’s uncertain” (BRACERS 79611). Hitherto she had worked for the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint committee established in May 1916 by the NCF, Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation, and which managed the records of individual C.O.s. This committee had its own premisses at 11 Adam St., off the Strand in the City of Westminster, London. After Rinder’s role in the NCF changed, she started working at the organization’s main office at 5 York Buildings, Adelphi.

- 7

mitigates my sympathy for Miss Ellis … accomplices … won’t pay Edith Maud Ellis (1878–1963; http://menwhosaidno.org/context/women/ellis_edith.html), the recently convicted treasurer of the Friends’ Service Committee, may have had some influence on the “removal” of Gladys Rinder from the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau (see note 6 above). This body represented Ellis’s Quaker organization and another religious pacifist group, as well as the NCF. Along with two other executive members of the Friends’ Service Committee, Harrison Barrow and Arthur Watts, Ellis was found guilty on 24 May 1918, under Defence of the Realm Regulation 27C (see note 9 to Letter 51), of printing and circulating a pamphlet, A Challenge to Militarism, before submitting it to the Official Press Bureau. Her two male “accomplices” were sentenced to six months’ imprisonment, while Ellis would spend three months in Holloway Prison after refusing to pay a £100 fine and 50 guineas costs (see Thomas C. Kennedy, The Hound of Conscience: a History of the No-Conscription Fellowship [Fayetteville: U. of Arkansas P., 1981], p. 243). During 1917 BR and Ellis had corresponded frequently about the welfare of C.O.s and the anti-conscription campaign, sometimes disagreeing over matters of policy and principle. Objecting, for example, to the disdain of Ellis and other Quakers for “alternativist” C.O.s working in Home Office camps, BR lamented that “we are ... developing the cruelty of fanaticism, which is the very spirit that supports the war” (11 Sept. 1917; Papers 14: xliii).

- 8

ordinary letters … manifesto Gladys Rinder was in charge of circulating parts of BR’s letters to his friends. Only suitable extracts were to be circulated. Sometimes they were sent weekly; there were also monthly compilations of extracts (e.g., May 1918, BRACERS 116559). Most of them were mimeographs, but sometimes typed carbons were circulated. Twenty people were on the list to receive letters. See S. Turcon, “Like a Shattered Vase: Russell’s 1918 Prison Letters”, Russell 30 (2010): 101–25; at 103.

- 9

her messageOttoline’s message, placed in Gladys Rinder’s letter to BR of 25 May 1918, reported on her driving-tour around the country with Philip Morrell, Siegfried Sassoon’s return to the Front, and a meeting with the former Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, and another leading Liberal, Sir John Simon. In addition, she conveyed a sympathetic greeting from H.W. Massingham and expressed her and Philip’s admiration for how BR was “going on creating and thinking in imprisonment” (BRACERS 79611). See also Part 2, Ch. 14 of Ottoline atGarsington: Memoirs of Lady Ottoline Morrell, 1915–1918, ed. R. Gathorne-Hardy (London: Faber and Faber, 1974).

- 10

thank Eliot for message In a message conveyed by Gladys Rinder’s letter to BR of 25 May 1918 (BRACERS 76911), T.S. Eliot expressed “a great relief to know that you are supplied with materials for labour, and I am waiting with great curiosity to know how your mind is going to work under these conditions.”

- 11

hope his wife is betterEliot had reported that his wife, Vivienne (née Haigh-Wood, 1888–1947), was “in very bad health” — a not uncommon occurrence, for she had long suffered from a variety of acute physical symptoms which affected her mental health and had a devastating impact on her marriage.

- 12

text-book of the Principia Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy (1919), a popular account of the main doctrines put forward in BR and Whitehead’s Principia Mathematica (1910–13). It is not to be confused with the “text-book to the Principia” mentioned in Letter 2, which was the projected “book on logic” (mentioned in Letter 5) to be based on “The Philosophy of Logical Atomism” lectures.

- 13

J.R.M. BR wrote “Macdonald” on a typed transcription (BRACERS 116566) of this letter to Frank. His note referred to the prominent dissenter and future Labour Prime Minister James Ramsay MacDonald.

- 14

position when I emerge … Murray hasn’t BR probably wanted to discuss with Wildon Carr the emerging fellowship plan, which he hoped would protect him from being called up after his imprisonment. Early in April Gilbert Murray had started a “philosophers’ petition” calling for BR’s academic work to be designated as of national importance. But that initiative had so far made little headway, no doubt in part because (until BR’s appeal) Murray had been preoccupied with a different memorial signed by professional philosophers, urging that BR’s sentence be served in the first division (see note 4 to Letter 6).

- 15

Santayana The reasons for Santayana’s exclusion will emerge shortly in the letter.

- 16

appear to be Two verbs are required to state a fact involving belief (e.g. that Othello believes that Desdemona loves Cassio). BR’s question was whether this is merely a matter of linguistic form or whether it reflects a feature of the fact being stated. The question was of considerable importance for his philosophy. See “The Philosophy of Logical Atomism”, Lecture IV (Papers 8: 191–200).

- 17

symbolism … the “proposition” Since 1910 BR had analysed propositions out of his philosophy. They were about to make a comeback, but not as mind-independent complexes of objects, as they were before 1910. This time they were to be complexes of images or words which were capable of representing states of affairs. Hence his interest in symbolism (and, to some extent, in psychology as well).

- 18

vagueness See BR’s paper “Vagueness”, Australasian Journal of Psychology and Philosophy 1 (June 1923): 84–92 (B&R C23.18); 23 inPapers 9. He initially discussed the concept in his prison review of Dewey’s Essays in Experimental Logic (Papers 8: 139–42).

- 19

wrote to Carr BR told Carr, “I want to subject Mind to the same kind of analysis as I applied to Matter in Knowledge of the External World. I do not know whether the result will be agreement with the neutral monists or not, but in any case it will be an attempt to arrive at the logically ultimate constituents of the phenomena one calls mental” (17 April 1918; BRACERS 54566; in Michael Thompson, “Some Letters of Bertrand Russell to Herbert Wildon Carr”, Coranto 10, no. 1 [1975]: 18). The problems that he spoke to Carr about were those of how to deal with belief and emphatic particulars, which he mentioned in Letter 5.

- 20

“logical atomism” BRused the term “logical atomism” to describe his philosophy after his break with Hegelianism in 1898. The phrase thus covers a variety of positions. The most canonical version is that expressed in his lectures “The Philosophy of Logical Atomism” (1918), on which the projected (but, alas, never written) book on the “Elements of Logic” was to be based.

- 21

Santayana’s Life of Reason George Santayana (1863–1952), Spanish-American philosopher. In 1918 Santayana was living in England, having retired from Harvard in 1912 thanks to an inheritance. He was a close friend of BR’s brother, Frank, and also of his brother-in-law, Logan Pearsall Smith. Although he was a religious man, his approach to philosophy was naturalistic, and he was strongly opposed to the idealism that dominated nineteenth-century philosophy in the wake of Hegel. Nonetheless, his five-volume The Life of Reason; or, The Phases of Human Progress (1905–06) was in part inspired by Hegel’s Phenomenology of Mind. But, unlike Hegel, Santayana wished to emphasize that the progress of the human mind through its various stages — common sense, society, religion, art, and science (one for each volume) — was that of an animal (albeit a rational one) living in the natural, material world. Santayana described it as “a summary history of the human imagination … distinguishing those phases of it which showed … an adaptation of fancy and habit to material facts and opportunities” (“A General Confession”, in P.A. Schilpp, ed., The Philosophy of George Santayana [New York: Tudor, 1951: 1st ed., 1940], pp. 13–14).

- 22

America is now in control The article in The Tribunal over which BR was prosecuted made much the same point about burgeoning American power and influence, albeit more sardonically (“The German Peace Offer”, no. 90 [3 Jan. 1918]: 1; Auto. 2: 79–81; 92 in Papers 14). The growing preponderance of the United States in world affairs was reinforced by its late entry into a war which had strained all the other belligerent states to the point of exhaustion. In barely a year the US had been transformed, in BR’s mind, from a possible saviour of European civilization (as an honest broker of peace) to its greatest threat, for he felt that American military intervention made any negotiated settlement of the war far less likely (see his prison manuscript, “The International Outlook” [unpublished at the time; 100 in Papers 14]).

- 23

since Brest-Litovsk … nothing for pacifists to do This separate peace between the Bolsheviks and the Central Powers (signed on 3 March 1918) formally ended Russian participation in the war and allowed Germany to concentrate its military resources on the Western Front. While Allied leaders were alarmed by the strategic implications of the treaty, British peace campaigners were disheartened by the grasping territorial gains made by the Central Powers at the expense of the former Tsarist Empire. Many, including BR, had argued hitherto that Germany would be amenable to a general peace without annexations or indemnities if only the Allies signalled their willingness to compromise. BR’s dismay at Germany’s harsh treatment of Russia only intensified during his imprisonment (see Papers 14: liv and Letter 18).

- 24

Whiteheads Alfred North Whitehead and Evelyn Whitehead.

- 25

Morse StephensThe Principal Speeches of the Statesmen and Orators of the French Revolution, 1789–1795, edited by H. Morse Stephens (2 vols., 1892).

- 26

2 books The books were: The Naturalist on the River Amazons (2 vols., 1863; with an introduction from Charles Darwin) by the Victorian naturalist Henry Walter Bates (1825–1892), who discovered 8,000 new species during eleven years in Brazil; and The Sea and the Jungle (1912), a travel book based on an expedition up the Amazon, by the novelist, essayist and The Nation’s literary editor, Henry Major Tomlinson (1873–1958). On 3 June 1918 Ottoline told Tomlinson that BR had “enjoyed the book enormously” and copied for him exactly what BR had said (BRACERS 122079).

- 27

Heart of Darkness Joseph Conrad’s novella, included in his Youth: a Narrative and Two Other Stories (Edinburgh: Blackwood, 1902) in which the narrator, Marlow, told of his arduous journey through equatorial Africa to meet Kurtz, the company’s most esteemed agent, who, however, reverted to barbarism in the heart of the jungle.

- 28

bit of Girondin history “This was a love letter to Colette incorporated in my official letter and passed by the Governor, because it was in French and professed to be from the Girondin Buzot to Madame Roland.” (BR’s note at BRACERS 116566.) The love letter is in Letter 7.

- 29

Delighted by G.J.’s last messageG.J. was in London “interviewing a friend” according to a message in a letter from Gladys Rinder on 25 May 1918 (BRACERS 79611).

- 30

Percy BR identified “Percy” on a note at BRACERS 116566: “Another pseudonym for Colette.” “Percy” was a nickname used by Colette’s family; she continued to use it in family correspondence decades later.

- 31

congratulations!Colette had said (via Rinder’s official letter, 25 May 1918, BRACERS 79611) that she was living on milk pudding and saving all her salary.

- 32

I enjoy joint lettersFrank and Elizabeth Russell had written their last letter jointly (19 May 1918, BRACERS 46914).

Textual Notes

- a

Analysis of Mind Quotation marks were editorially replaced by italics.

- b

atomic Inserted before “facts”.

- c

leaves pictures Corrected editorially from “leave pictures”.

- d

with Bates Inserted.

- e

Tell Lady O. … sane with lies This well-known passage is marked off with short pencilled lines. It and the “I review the past” passage below were typed together and made to follow, as if part of, the letter to Rinder of 19 August 1918 (BRACERS 76940). BR even corrected the typing (BRACERS 117622): a gap was left after “all who care for the world’s”. He filled the gap first with “salvation”, then with “welfare”. There is no gap in the original letter, which has “welfare”. The first passage was printed at Auto. 2: 36.

- f

Delighted by G.J.’s last message. The sentence was inserted.

- g

I review the past … world’s welfare. This well-known passage is marked off with short pencilled lines.

- h

I am bankrupt … bring it Wednesday. Inserted above the salutation.

A.N. Whitehead

Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947), Cambridge-educated mathematician and philosopher. From 1884 to 1910 he was a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, and lecturer in mathematics there; from 1911 to 1924 he taught in London, first at University College and then at the Imperial College of Science and Technology; in 1924 he took up a professorship in philosophy at Harvard and spent the rest of his life in America. BR took mathematics courses with him as an undergraduate, which led to a lifelong friendship. Whitehead’s first major work was A Treatise on Universal Algebra (1898), which treated selected mathematical theories as “systems of symbolic reasoning”. Like BR’s The Principles of Mathematics (1903), it was intended as the first of two volumes; but in 1900 he and BR discovered Giuseppe Peano’s work in symbolic logic, and each decided to set aside his projected second volume to work together on a more comprehensive treatment of mathematics using Peano’s methods. The result was the three volumes of Principia Mathematica (1910–13), which occupied the pair for over a decade. After Principia was published, Whitehead’s interests, like BR’s, turned to the empirical sciences and, finally, after his move to America, to pure metaphysics. See Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: the Man and His Work, 2 vols. (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins U. P., 1985–90).

Annotations by BR

In the late 1940s, when BR was going through his archives, and in the 1950s when he was revising his Autobiography, he would occasionally annotate letters. He did this to sixteen of the Brixton letters. Links to them are gathered here for convenient access to these new texts. In the annotations to the letters they are always followed by “(BR’s note.)”

Letter 2, note 5 happy.

5, note 6 congratulations to G.J.

9, note 28 bit of Girondin history.

12, note 6 friend.

15, note 2 (the letter in general).

20, note 7 G.J.

31, note 3 Dr’s treatment.

40, notes 9, 10 Ld. G.L.G, Lady B’s.

44, note 14 S.S.

48, note 48 Mother Julian’s Bird.

57, notes 13, 16 Ld. Granville’s to Ly. B., bless that Dr. … seat of intellect.

70, note 15 Mrs Scott.

73, note 12 E.S.P. Haynes.

76, note 4 Cave.

85, note 2 Marsh on Rupert.

102, notes 23, 28 Woolley, K. Lonsdale.

General Annotations

Brett note from Auto. 2: 93

Cousens note from Auto. 2: 71

Kyle note with her letters to BR

Rinder note from Auto. 2: 88n.

Silcox note on BRACERS 80365

Boismaison

Colette and BR vacationed at a house, The Avenue, owned by Mrs. Agnes Woodhouse and her husband, in the countryside near Ashford Carbonel, Shropshire, in August 1917. They nicknamed the house “Boismaison”. Agnes Woodhouse took in paying guests. Their first visit was idyllic. They returned for other vacations — in 1918 before he entered prison and in April 1919. Their plan to go soon after he got out of prison failed because their relationship faltered for a time. They discussed returning in the summer of 1919 — a booking was even made for 12–19 July — but in the end they didn’t go. See S. Turcon, “Then and Now: Bertie and Colette’s Escapes to the Peak District and Welsh Borderlands”, Russell 34 (2014): 117–30.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.

Dr. Alfred Salter

Dr. Alfred Salter (1873–1945), socialist and pacifist physician, replaced BR as Acting Chairman of the NCF in January 1918. For two decades he had been dedicated both professionally and politically to the working-class poor of Bermondsey. In 1898 Salter moved there into a settlement house founded by the Rev. John Scott Lidgett to minister to the health, social and educational needs of this chronically deprived borough in south-east London. In establishing a general practice in Bermondsey, Salter forsook the very real prospect of advancement in the medical sciences (at which he had excelled as a student at Guy’s). Shortly after his marriage to fellow settlement house worker Ada Brown in 1900, the couple joined the Society of Friends and Salter became active in local politics as a Liberal councillor. In 1908 he became a founding member of the Independent Labour Party’s Bermondsey branch and twice ran for Parliament there under its banner before winning the seat for the ILP in 1922. Although he lost it the following year, he was again elected in October 1924 and represented the constituency for the last twenty years of his life, during which he remained a consistently strong pacifist voice inside the ILP. Salter was an indefatigable organizer whose steely political will and fixed sense of purpose made him, in BR’s judgement, inflexible and doctrinaire when it came to the nuances of conscientious objection. See Oxford DNB and A. Fenner Brockway, Bermondsey Story: the Life of Alfred Salter (London: Allen & Unwin, 1949).

Elizabeth Russell

Elizabeth Russell, born Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941), was a novelist who in 1891 married Graf von Arnim-Schlagenthin. She became known as “Elizabeth”, the name she used in publishing Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898), and she remained widely known as Elizabeth von Arnim, although the Library of Congress catalogues her as Mary Annette (Beauchamp), Countess von Arnim. She was a widow when she married BR’s brother, Frank, on 11 February 1916. The marriage was quickly in difficulty; she left it for good in March 1919, but they were never divorced and she remained Countess Russell (becoming Dowager Countess after Frank’s death in 1931).

Eva Kyle

Eva Kyle ran a typing service. She did work for the No-Conscription Fellowship and took BR’s dictation of his book, Roads to Freedom, in the early months of 1918. He annotated a letter from her: “She was an admirable typist but very fat. We all agreed that she was worth her weight in gold, though that was saying a great deal.” Her prison letter to him is clever and amusing. She typed his major prison writings and apologized for the amount of the invoice when he emerged.

Evelyn Whitehead

Evelyn (Willoughby-Wade) Whitehead (1865–1961). Educated in a French convent, she married Alfred North Whitehead in 1891. Her suffering, during an apparent angina attack, inspired BR’s profound sympathy and occasioned a storied episode which he described as a “mystic illumination” (Auto. 1: 146). Through her he supported the Whitehead family finances during the writing of Principia Mathematica. During the early stages of his affair with Ottoline Morrell, she was BR’s confidante. They maintained their mutual affection during the war, despite the loss of her airman son, Eric. BR last visited Evelyn in 1950 in Cambridge, Mass., when he found her in very poor health.

Fellowship Plan

Since the upper-age limit for compulsory military service had been increased to 50 in April 1918, BR was faced with the unnerving prospect of being conscripted after his release from Brixton. Early in his imprisonment he was already wondering about his “position when I emerge from here” (Letter 9). While his conviction was still under appeal, he had broached with Clifford Allen and Gilbert Murray the possibility of avoiding military service, not by asserting his conscientious objection to it, but by obtaining accreditation of his philosophical research as work of national importance (see note to Letter 24). The Pelham Committee, set up by the Board of Trade in March 1916, was responsible for the designation of essential occupations and recommending to the local tribunals, who adjudicated claims for exemption from military service, that C.O.s be considered for such positions. BR reasoned to Murray on 2 April that a dispensation to practise philosophy (as opposed to working outside his profession), would enable to him to “avoid prison without compromise” — i.e., of his political and moral opposition to conscription (BRACERS 52367). Although BR intended to withdraw from political work, he told Murray two days later, he would not promise to abstain from peace campaigning (BRACERS 52369). It should be noted that C.O.s who accepted alternative service in special Home Office camps were expressly prohibited from engaging in pacifist activities (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 231).

BR was far from sanguine about the prospect of success before a local tribunal. But he came to think (by early June) that his chances would be improved if his academic supporters interceded directly with the Minister of National Service, Sir Auckland Geddes. In addition, he calculated that such entreaties would be more effective if those acting on his behalf could secure and even endow a fellowship for him and thereby have “something definite to put before Geddes” (Letter 12; see also Letters 15 and 19). BR definitely wanted to rededicate himself to philosophy and would have welcomed a new source of income from academic employment (see Letter 22). But the “financial aspect was quite secondary”, he reminded Frank on 24 June (Letter 27); he was interested in the fellowship plan primarily as a safeguard against being called up, for teachers over 45 were not subject to the provisions of the recently amended Military Service Act. In the same letter, however, BR told his brother that “I wish it <the plan> dropped” on account of reservations expressed to him in person by Wildon Carr and A.N. Whitehead (see also Letter 31), two philosophers whom he respected but who seemed to doubt whether BR’s financial needs were as great as they appeared (see note to Letter 102).

Yet BR’s retreat was only temporary. On 8 August, he expressed to Ottoline a renewed interest in the initiative, and a few days later, she, her husband and Gladys Rinder met in London to discuss the matter. As Ottoline reported to BR, “we all felt that it was useless to wait for others to start and we decided that P. and I should go and see Gilbert M. and try and get him to work it with the Philosophers” (11 Aug. 1918, BRACERS 114754). BR probably wanted Murray to spearhead this lobbying (see also Letters 65 and 70) because of his political respectability and prior success in persuading professional philosophers to back an appeal to the Home Secretary for BR’s sentence to be served in the first division (see Letter 6). Murray did play a leading role but not until early the following month, when BR was anxious for the fellowship plan to succeed as his release date neared. The scheme finally gathered momentum after a meeting between Ottoline, Rinder and Carr on 6 September 1918, at which the philosopher and educationist T. Percy Nunn, another academic supporter of BR, was also present. Within a few days Murray had drafted a statement with an appeal for funds, which was endorsed by Carr, Whitehead, Nunn, Samuel Alexander, Bernard Bosanquet, G. Dawes Hicks, A.E. Taylor and James Ward. This memorial was then circulated in confidence to philosophers and others, but only after BR’s release from Brixton. (Financial pledges had already been made by a few of BR’s friends and admirers, notably Lucy Silcox and Siegfried Sassoon.) BR’s solicitor, J.J. Withers, became treasurer of this endowment fund, the goal of which was to provide BR with £150 or £200 per annum over three years. On 30 August BR had confessed to Ottoline that he did not want an academic position “very far from London” (Letter 89) and reiterated this desire in a message to Murray communicated by Rinder (Letter 97). On 6 September Rinder (BRACERS 79633) hinted that she already knew where the appointment would be, but there are no other indications that a particular establishment had been decided upon. Ultimately, no affiliation was contemplated for BR, so the memorial stated, because “in the present state of public feeling no ordinary university institution is likely to be willing to employ him as a teacher” (copy in BRACERS 56750). The circular talked instead of a “special Lectureship”, and the £100 BR received from the fund early in 1919 was explicitly issued as payment for lectures (on “The Analysis of Mind”; see syllabus, in Papers 9: App. III.1) that he would deliver that spring. BR’s solicitor also informed him that provision existed to pay him a further £100 for an autumn lecture course (see syllabus, ibid.: App. III.2), and Withers anticipated that these arrangements might “last two or three years” (2 Jan. 1919, BRACERS 81764). BR had already obtained a £50 gift from the fund in November 1918. Somewhat ironically, the critical importance of a teaching component to the fellowship plan — as insurance against conscription — was reduced by the authorities hesitating to hound BR any further after his imprisonment, and all but nullified by the end of the war a few weeks later. (There were no fresh call-ups, but the last of the C.O.s already in prison were not released until August 1919, and conscription remained in effect until April 1920.)

First Division

As part of a major reform of the English penal system, the Prison Act (1898) had created three distinct categories of confinement for offenders sentenced to two years or less (without hard labour) in a “local” prison. (A separate tripartite system of classification applied to prisoners serving longer terms of penal servitude in Britain’s “convict” prisons.) For less serious crimes, the courts were to consider the “nature of the offence” and the “antecedents” of the guilty party before deciding in which division the sentence would be served. But in practice such direction was rarely given, and the overwhelming majority of offenders was therefore assigned third-division status by default and automatically subjected to the harshest (local) prison discipline (see Victor Bailey, “English Prisons, Penal Culture, and the Abatement of Imprisonment, 1895–1922”, Journal of British Studies 36 [1997]: 294). Yet prisoners in the second division, to which BR was originally sentenced, were subject to many of the same rigours and rules as those in the third. Debtors, of whom there were more than 5,000 in local prisons in 1920, constituted a special class of inmate, whose less punitive conditions of confinement were stipulated in law rather than left to the courts’ discretion.

The exceptional nature of the first-division classification that BR obtained from the unsuccessful appeal of his conviction should not be underestimated. The tiny minority of first-division inmates was exempt from performing prison work, eating prison food and wearing prison clothes. They could send and receive a letter and see visitors once a fortnight (more frequently than other inmates could do), furnish their cells, order food from outside, and hire another prisoner as a servant. As BR’s dealings with the Brixton and Home Office authorities illustrate, prison officials determined the nature and scope of these and other privileges (for some of which payment was required). “The first division offenders are the aristocrats of the prison world”, concluded the detailed inquiry of two prison reformers who had been incarcerated as conscientious objectors: “The rules affecting them have a class flavour … and are evidently intended to apply to persons of some means” (Stephen Hobhouse and A. Fenner Brockway, eds., English Prisons To-day [London: Longmans, Green, 1922], p. 221). BR’s brother described his experience in the first division at Holloway prison, where he spent three months for bigamy in 1901, in My Life and Adventures (London: Cassell, 1923), pp. 286–90. Frank Russell paid for his “lodgings”, catered meals were served by “magnificent attendants in the King’s uniform”, and visitors came three times a week. In addition, the governor spent a half-hour in conversation with him daily. At this time there were seven first-class misdemeanants, who exercised (or sat about) by themselves. Frank concluded that he had “a fairly happy time”, and “I more or less ran the prison as St. Paul did after they had got used to him.” BR’s privileges were not quite so splendid as Frank’s, but he too secured a variety of special entitlements (see Letter 5).

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).

French Revolution Reading

In Letter 2 (6 May 1918) BR instructed his brother to ask Evelyn Whitehead to “recommend books (especially memoirs) on French Revolution”, and reported that he was already reading “Aulard” — presumably Alphonse Aulard’s Histoire politique de la révolution française (Paris: A. Colin, 1901). In a message to Ottoline sent via Frank ten days later (Letter 5), BR hinted that he was especially interested in the period after August 1792, which he felt was “very like the present day”. On 27 May (Letter 9), he conveyed to Frank his disappointment that Evelyn had not yet procured for him any memoirs of the revolutionary era, and that Eva Kyle had only furnished him with The Principal Speeches of the Statesmen and Orators of the French Revolution, 1789–1795, ed. H. Morse Stephens, 2 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1892). This was “not the sort of book I want, BR complained”, but “an old stager history which I have read before” (in Feb. 1902: “What Shall I Read?”, Papers 1: 365). Fortunately, some of the desired literature reached him shortly afterwards, including The Private Memoirs of Madame Roland, ed. Edward Gilpin Johnson (London: Grant Richards, 1901: see Letter 12) — or else a different edition of the doomed Girondin’s prison writings — and the Memoirs of the Comtesse de Boigne, ed. Charles Nicoullaud, 3 vols. (London: Heinemann, 1907: see Letter 15). In Letter 48, BR told Ottoline that he was “absorbed in a 3-volume Mémoire” of the Comte de Mirabeau. The edition has not been identified, but quotations attributed to the same aristocratic revolutionary in Letter 44 appear in Lettres d’amour de Mirabeau, précédées d’une étude sur Mirabeau par Mario Proth (Paris: Garnier Frères, 1874). Some weeks after writing Letter 11 to Colette as one purportedly from Mirabeau to Sophie de Monier (sic), BR actually read the lovers’ prison correspondence, possibly in Benjamin Gastineau’s edition: Les Amours de Mirabeau et de Sophie de Monnier, suivis des lettres choisies de Mirabeau à Sophie, de lettres inédites de Sophie, et du testament de Mirabeau par Jules Janin (Paris: Chez tous les libraires, 1865). BR’s reading on the French Revolution also included letters from Études révolutionnaires, ed. James Guillaume, 2 vols. (Paris: Stock, 1908–09), the collection he misleadingly cited as the source for two other illicit communications to Colette (Letters 8 and 10). Also of relevance (Letter 57) were Napoleon Bonaparte’s letters to his first wife, Joséphine de Beauharnais, which BR may have read in this well-known English translation edited by Henry Foljambe Hall: Letters to Josephine, 1796–1812 (London: J.M. Dent, 1901). Finally, BR obtained a hostile, cross-channel perspective on the French Revolution and Napoleon from Lord Granville’s Private Correspondence, 1781–1821, ed. Castalia, Countess Granville, 2 vols. (London: J. Murray, 1917: see Letters 40, 41 and 44). Commenting towards the end of his sentence on the mental freedom that he had been able to preserve in Brixton, BR wrote about living “in the French Revolution” among other times and places (Letter 90). His immersion in this tumultuous era may have been deeper still if he perused other works not mentioned in his Brixton letters — which he may well have done. Yet BR’s examination of the French Revolution was not at all programmatic (as intimated perhaps by his preference for personal accounts (diaries and letters in addition to memoirs) — unlike much of his philosophical prison reading. Although his political writings are scattered with allusions to the French Revolution (in which he was interested long before Brixton), BR never produced a major study of it. Just over a year after his imprisonment, however, he did publish a scathing and even profound review of reactionary author Nesta H. Webster’s history of the French Revolution, which certainly drew on his reservoir of knowledge about the period (“The Seamy Side of Revolution”, The Athenaeum, no. 4,665 [26 Sept. 1919]: 943–4; Papers 15: 19). While imprisoned briefly in Brixton for a second time, in September 1961, Russell returned to the era of the French Revolution and Napoleon, “enjoying … immensely” (Letter 105) this biography of Mme. de Staël: J. Christopher Herold, Mistress to an Age: a Life of Madame de Staël (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1959; Russell’s library).

Gilbert Murray

Gilbert Murray (1866–1957), distinguished classical scholar and dedicated liberal internationalist. He was Regius Professor of Greek at Oxford, 1908–36, and chair of the League of Nations Union, 1923–36. He and BR enjoyed a long and close friendship that was ruptured temporarily by bitter disagreement over the First World War. After Murray published The Foreign Policy of Sir Edward Grey, 1906–1915, in defence of Britain’s pre-war diplomacy, BR responded with a detailed critique, The Policy of the Entente, 1904–1914: a Reply to Professor Gilbert Murray (37 in Papers 13). Yet Murray still took the lead in campaigning to get BR’s sentence reassigned from the second to the first division and (later) in leading an appeal for professional and financial backing of an academic appointment for BR upon his release (the “fellowship plan”, which looms large in his prison correspondence). BR was still thankful for Murray’s exertions some 40 years later. See his portrait of Murray, “A Fifty-Six Year Friendship”, in Murray, An Unfinished Autobiography with Contributions by His Friends, ed. Jean Smith and Arnold Toynbee (London: Allen & Unwin, 1960).

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Governor of Brixton Prison / Carleton Haynes

Captain Carleton Haynes (1858–1945), the Governor of Brixton Prison in 1918, was a retired army officer and a cousin of BR’s acquaintance, the radical lawyer and author E.S.P. Haynes. In March 1919 BR sent Haynes, in jest, a copy (now in the Russell Archives) of his newly published Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy — so that the governor’s collection of works written by inmates while under his charge would “not ... be incomplete” (BRACERS 123167).

H. Wildon Carr

Herbert Wildon Carr (1857–1931), Professor of Philosophy at King’s College, London, from 1918 and Visiting Professor at the University of Southern California from 1925. Carr came to philosophy late in life after a lucrative career as a stockbroker. His philosophy was an idiosyncratic amalgam of Bergsonian vitalism and Leibnizian monadology, which, he thought, was supported by modern biology and the theory of relativity. He wrote books on Bergson and Leibniz at opposite ends of his philosophical career and a book on relativity in the middle. His philosophy would have made him an unlikely ally of BR’s, but it was Carr who organized BR’s two courses of public lectures, on philosophy of mathematics and the philosophy of logical atomism, which brought BR back to philosophy and improved his finances in 1917–18. Carr had great administrative talents, which he employed also on behalf of the Aristotelian Society during his long association with it. He was its president in 1916–18 and continued to edit its Proceedings until 1929.

H.W. Massingham

H.W. Massingham (1860–1924), radical journalist and founding editor in 1907 of The Nation, a publication which superseded The Speaker and soon became Britain’s foremost Liberal weekly. Almost immediately the editor of the new periodical started to host a weekly luncheon (usually at the National Liberal Club), which became a vital forum for the exchange of “New Liberal” ideas and strategies between like-minded politicians, publicists and intellectuals (see Alfred F. Havighurst, Radical Journalist: H.W. Massingham, 1860–1924 [Cambridge: U. P., 1974], pp. 152–3). On 4 August 1914, BR attended a particularly significant Nation lunch, at which Massingham appeared still to be in favour of British neutrality (see Papers 13: 6) — which had actually ended at the stroke of midnight. By the next day, however, Massingham (like many Radical critics of Britain’s pre-war diplomacy) had come to accept the case for military intervention, a position he maintained (not without misgivings) for the next two years. Massingham was still at the helm of the Nation when it merged with the more literary-minded Athenaeum in 1921; he finally relinquished editorial control two years later. In 1918 he served on Miles and Constance Malleson’s Experimental Theatre Committee.

J. Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (1866–1937) was a prominent dissenter and founding member of the Union of Democratic Control. He had resigned as chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party after most of his colleagues voted for the Asquith Government’s war budget in August 1914. After regaining the Labour leadership, MacDonald formed two minority administrations (1924 and 1929–31). He was still in office when he was persuaded, by an acute financial crisis, to accept the premiership of a Conservative-dominated National Government — thereby incurring the wrath of his party (from which he was expelled) for reasons quite different than in the First World War. BR respected MacDonald’s wartime politics but came to regard him as excessively timid and deferential. He later complained how, after becoming Prime Minister, MacDonald “went to Windsor in knee-breeches” (Auto. 2: 129).

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

Philip Morrell

Philip Morrell, Ottoline’s husband (1870–1943), whom she had married in 1902 and with whom, four years later, she had twins — Julian, and her brother, Hugh, who died in infancy. The Morrells were wealthy Oxfordshire brewers, although Philip’s father was a solicitor. He won the Oxfordshire seat of Henley for the Liberal Party in 1906 but held this Conservative stronghold only until the next general election, four years later. For the second general election of 1910 he ran successfully for the Liberals in the Lancashire manufacturing town of Burnley. But Morrell’s unpopular anti-war views later cost him the backing of the local Liberal Association, and his failure to regain the party’s nomination for the post-war election of 1918 (see Letter 89) effectively ended his short political career. Unlike many other Liberal critics of British war policy (including BR), Morrell did not transfer his political allegiance to the Labour Party. Although Ottoline and her husband generally tolerated each other’s extra-marital affairs, a family crisis ensued when in 1917 Philip impregnated both his wife’s maid and his secretary (see Letter 48).

Principia Mathematica

Principia Mathematica, the monumental, three-volume work coauthored with Alfred North Whitehead and published in 1910–13, was the culmination of BR’s work on the foundations of mathematics. Conceived around 1901 as a replacement for the projected second volumes of BR’s Principles of Mathematics (1903) and of Whitehead’s Universal Algebra (1898), PM was intended to show how classical mathematics could be derived from purely logical principles. For a large swath of arithmetic this was done by actually producing the derivations. A fourth volume on geometry, to be written by Whitehead alone, was never finished. In 1925–27 BR, on his own, produced a second edition, adding a long introduction, three appendices and a list of definitions to the first volume and corrections to all three. (See B. Linsky, The Evolution of Principia Mathematica [Cambridge U. P., 2011].) In this edition, under the influence of Wittgenstein, he attempted to extensionalize the underlying intensional logic of the first edition.

Siegfried Sassoon

Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967), soldier awarded the MC and anti-war poet. Ottoline had befriended him in 1916, and the following year, when Sassoon refused to return to his regiment after being wounded, she and BR helped publicize this protest, which probably saved him from a court martial. BR even assisted Sassoon in revising his famous anti-war statement, which was read to the House of Commons by a Liberal M.P. on 30 July 1917. Sassoon’s actions were an embarrassment to the authorities, for he was well known as both a poet and a war hero. Unable to hush the case up, the government acted with unexpected subtlety and declared Sassoon to be suffering from shell-shock and sent him to Craiglockhart War Hospital for Officers, near Edinburgh. After a period of recuperation in Scotland overseen by military psychiatrist Capt. W.H.R. Rivers, Sassoon decided to return to the Front (see Jean Moorcroft Wilson, Siegfried Sassoon: Soldier, Poet, Lover, Friend [New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2014]). He was again wounded in July 1918 and was convalescing in Britain during some of BR’s imprisonment. Although each admired the other’s stand on the war, BR and Sassoon were never close in later years. Yet Sassoon did pledge £50 to the fellowship plan fund (see BRACERS 114758), and decades later he donated a manuscript in support of BR’s International War Crimes Tribunal (see BRACERS 79066).

T.S. Eliot

The poet and critic Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888–1965) was a student of BR’s at Harvard in 1914. BR had sensed his ability, especially “a certain exquisiteness of appreciation” (to Lucy Donnelly, 11 May 1914; SLBR 1: 491), but did not see a genius in embryo. After Eliot travelled to England later the same year, to study philosophy at Oxford under H.H. Joachim, BR became something of a father figure to the younger man. He also befriended Eliot’s (English) wife, Vivienne, whom he had hastily married in 1915 and with whom BR may have had an affair the following year. BR shared his Bloomsbury apartment (at 34 Russell Chambers) with the couple for more than a year after their marriage, and jointly rented a property with them in Marlow, Bucks. (see Letter 78). He further eased Eliot’s monetary concerns by arranging paid reviewing for him and giving him £3,000 in debentures from which BR was reluctant, on pacifist grounds, to collect the income (Auto. 2: 19). Eliot’s financial security was much improved by obtaining a position at Lloyd’s Bank in 1917, but during BR’s imprisonment he faced uncertainty of a different kind as the shadow of conscription loomed over him (see, e.g., Letter 27). Nine years after the war ended Eliot returned the securities (BRACERS 76480).

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).