Brixton Letter 8

BR to Constance Malleson

May 26, 1918

- ALS

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-8

BRACERS 19309

<Brixton Prison>1

<c.26 May 1918>2

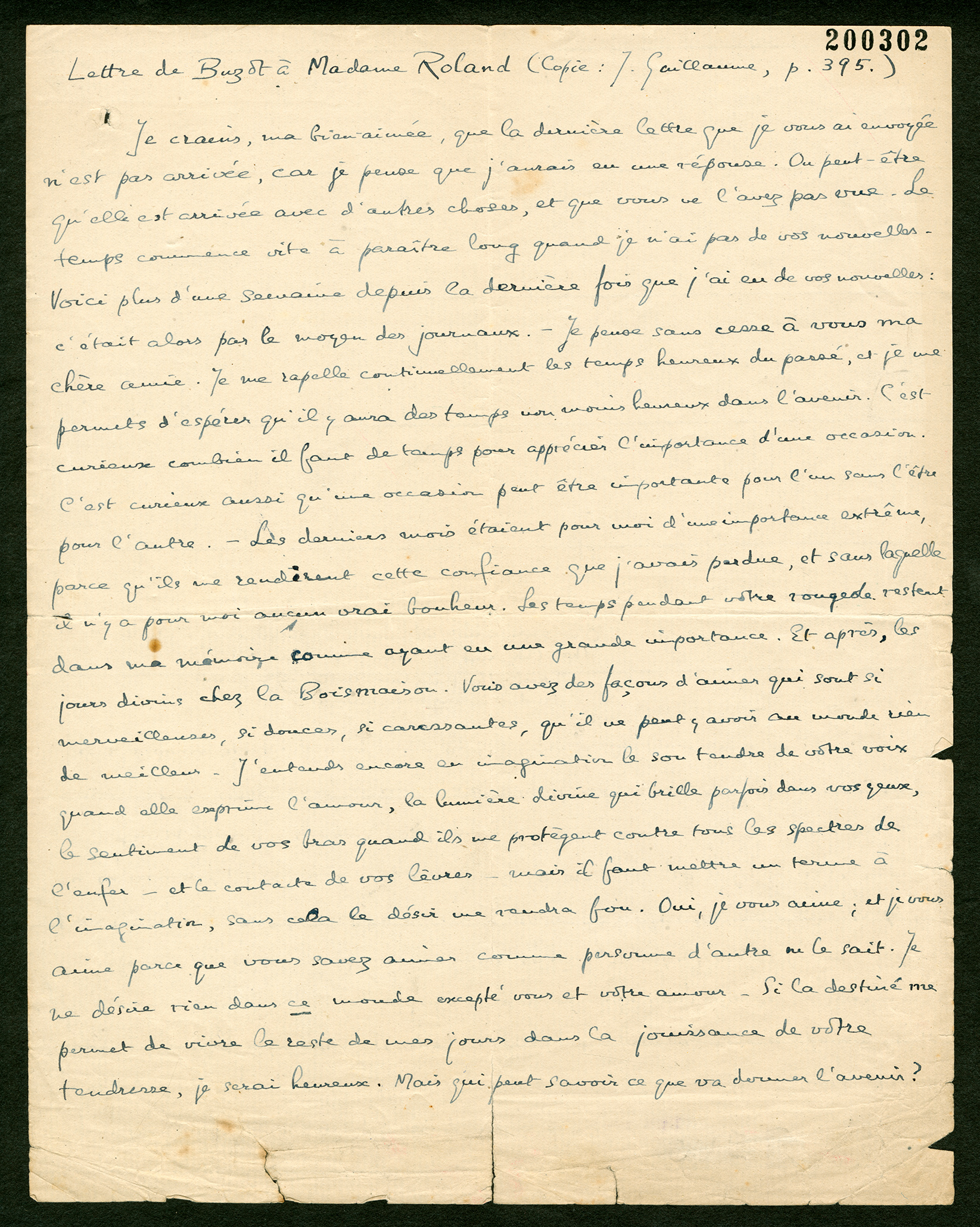

Lettre de Buzot à Madame Roland3 (Copie:4 J. Guillaume,5 p. 395.)

Je crains, ma bien-aimée, que la dernière lettre que je vous ai envoyée6 n’est pas arrivée, car je pense que j’aurais eu une réponse. Ou peut-être qu’elle est arrivée avec d’autres choses, et que vous ne l’avez pas vue. Le temps commence vite à paraître long quand je n’ai pas de vos nouvelles. Voici plus d’une semaine7 depuis la dernière fois que j’ai eu de vos nouvelles: c’était alors par le moyen des journaux. — Je pense sans cesse à vous ma chère amie. Je me rapellea continuellement les temps heureux du passé, et je me permets d’espérer qu’il y aura des temps non moins heureux dans l’avenir. C’est curieux combien il faut de tempsb pour apprécier l’importance d’une occasion. C’est curieux aussi qu’une occasion peut être importante pour l’un sans l’être pour l’autre. — Les derniers mois étaient pour moi d’une importance extrême, parce qu’ils me rendirent cette confiance que j’avais perdue, et sans laquelle il n’y a pour moi aucun vrai bonheur. Les temps pendant votre rougeole8 restent dans ma mémoire comme ayant eu une grande importance. Et après, les jours divins chez la Boismaison. Vous avez des façons d’aimer qui sont si merveilleuses, si douces, si caressantes, qu’il ne peut y avoir au monde rien de meilleur. J’entends encore en imagination le son tendre de votre voix quand elle exprime l’amour, la lumière divine qui brille parfois dans vos yeux, le sentiment de vos bras quand ils me protègent contre tous les spectres de l’enfer — et le contactec de vos lèvres — mais il faut mettre un terme à l’imagination, sans cela le désir me rendra fou. Oui, je vous aime; et je vous aime parce que vous savez aimer comme personne d’autre ne le sait. Je ne désire rien dans ce monde excepté vous et votre amour. Si la destinéd me permet de vivre le reste de mes jours dans la jouissance de votre tendresse, je serai heureux. Mais qui peut savoir ce que va donner l’avenir?

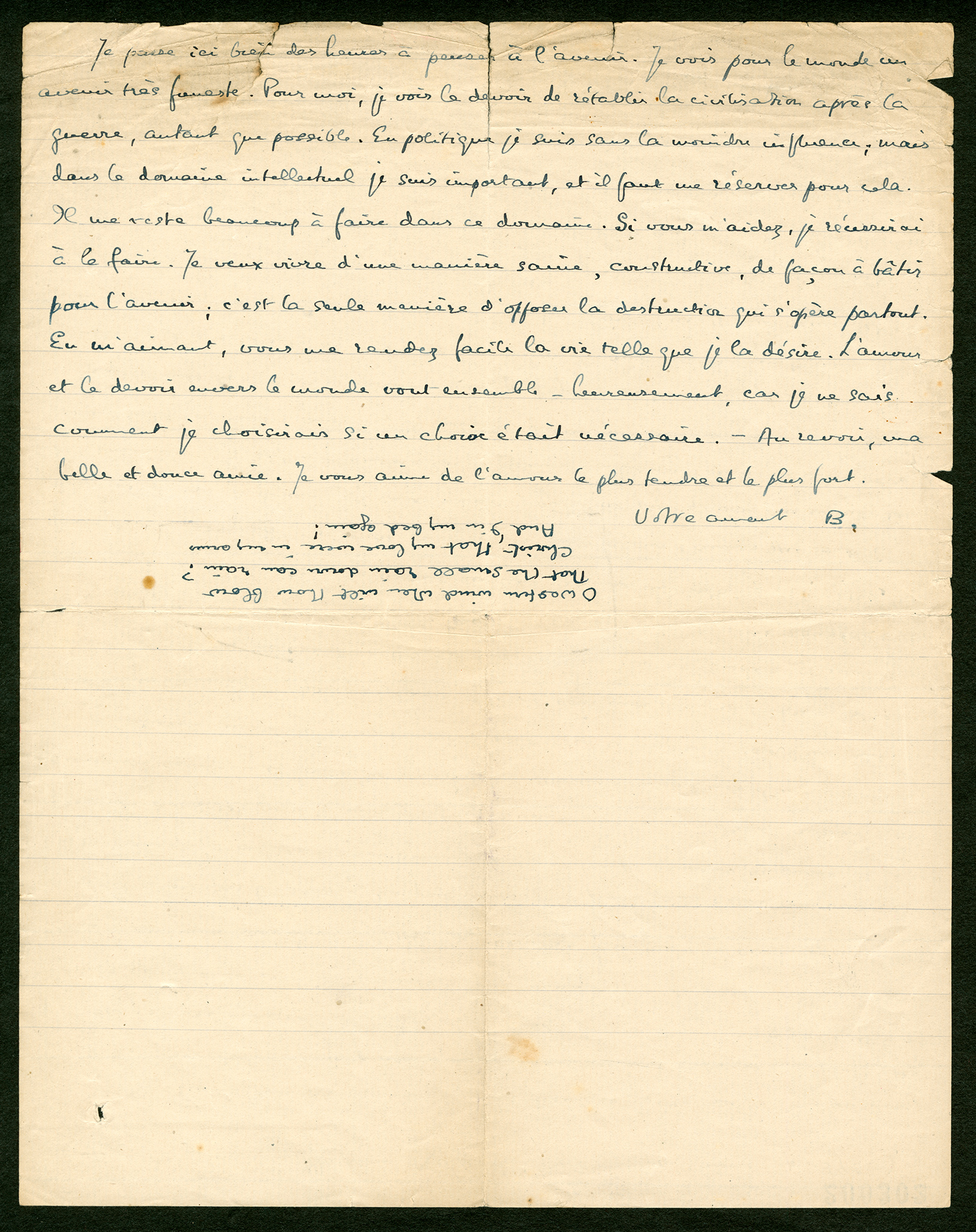

Je passe ici bien des heures à penser à l’avenir. Je vois pour le monde un avenir très funeste. Pour moi, je vois le devoir de rétablir la civilisation après la guerre, autant que possible. En politique je suis sans la moindre influence; mais dans le domaine intellectuel je suis important, et il faut me réserver pour cela. Il me reste beaucoup à faire dans ce domaine. Si vous m’aidez, je réussirai à le faire. Je veux vivre d’une manière saine, constructive, de façon à bâtir pour l’avenir; c’est la seule manière d’opposer la destruction qui s’opère partout. En m’aimant, vous me rendez facile la vie telle que je la désire. L’amour et le devoir envers le monde vont ensemble — heureusement, car je ne sais comment je choisirais si un choix était nécessaire. — Au revoir, ma belle et douce amie. Je vous aime de l’amour le plus tendre et le plus fort.

Votre amant

B.

<Translation:>

Letter from Buzot to Madame Roland (copy: J. Guillaume, p. 395.)

I’m afraid, my beloved, that my last letter that I sent you didn’t arrive, because I think I should have had an answer. Maybe it arrived mixed in with other things, and you didn’t see it. Time seems to pass slowly when I haven’t had your news. It’s been more than a week since I last had your news: it was then through the newspapers. — I think constantly about you my darling friend. I continually remember the happy times of the past, and I allow myself to hope there will be no less happy times in the future. It’s curious how much time it takes to appreciate the importance of an occasion. It’s also curious that an occasion can have importance for one without being important for the other. — These last months were extremely important to me, because they gave me confidence that I had lost, and without which there isn’t for me any real happiness. The time during your measles stays in my memory as having great importance. And after, the divine days at the Woodhouses’. You have ways of loving which are so marvellous, so sweet, so caressing, that there couldn’t be anything in this world that’s better. I listen again with my imagination to the tender sound of your voice when it expresses love, the divine light that sometimes shines in your eyes, the feeling of your arms when they protect me against all the spectres of hell — and the touch of your lips — but it’s necessary to put an end to imagination, otherwise desire will make me mad. Yes, I love you; and I love you because you know how to love like no one else I know. I don’t desire anything in this world except you and your love. If destiny allows me to live the rest of my days in the joy of your tenderness, I shall be happy. But who knows what the future will bring?

I spend many hours here thinking about the future. I see for the world a disastrous future. For myself, I see work to reestablish civilization after the war, as much as possible. In politics I am without the least influence; but in the intellectual domain I am important, and I must retain that. There’s still a lot for me to do in this domain. If you help me, I shall succeed in doing it. I want to live in a healthy, constructive way, so as to build for the future; it’s the only way to oppose the destruction that operates everywhere. In loving me, you make the kind of life I desire easy. Love and duty to the world go together — fortunately, because I don’t know how I would choose if a choice were necessary. — Goodbye, my beautiful and dear friend. I love you with the most tender and strongest love.

Your lover,

B.

O western wind when wilt thou blow

that the small rain down can rain?

Christ, that my love were in my arms

And I in my bed again!9, e

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the initialled original in BR’s handwriting in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. BR filled one and a half sides of the sheet (ruled on one side) and folded it twice.

- 2

[date] BR states in the letter that he has not heard from Colette since her message more than a week earlier in The Times, 18 May 1918. She was soon to visit him (see Letter 10).

- 3

Buzot à Madame Roland François Nicolas Léonard Buzot (1760–1794), a far-left Girondin deputy in the French National Assembly. His love affair with Madame Roland (née Marie-Jeanne Philipon, 1754–1793) started in 1792, a few months before she was arrested and he had to flee for his life. They smuggled letters to each other while she was in jail and he in hiding. He committed suicide to avoid arrest six months after she was executed.

- 4

Copie “Copie” was part of the ruse to make it appear BR was copying from a book.

- 5

J. Guillaume James Guillaume (1844–1916) was a French historian (and a translator and anthologizer of Bakunin: see Letter 61). BR had evidently been reading his Études révolutionnaires (2 vols., 1908–09), which include a number of letters from the French Revolution although none by Buzot.

- 6

la dernière lettre que je vous ai envoyée No previous letter to Colette during the Brixton period is known; BR may have meant his “Buzot letter” copied into Letter 7.

- 7

plus d’une semaineColette’s latest message in The Times Personals was on 18 May (BRACERS 96081).

- 8

votre rougeole She had had the measles in early March 1918.

- 9

O western wind ... again! This anonymous poem is from the early sixteenth century. The text, as it appears in Early English Lyrics, Amorous, Divine, Moral and Trivial, ed. E.K. Chambers and F. Sidgwick (London: A.H. Bullen, 1907), p. 69, is: “Western wind, when will thou blow? / The small rain down can rain. / Christ, if my love were in my arms, / And I in my bed again!”

Textual Notes

- a

rapelle The correct French spelling is “rappelle”.

- b

de temps The correct French is “du temps”.

- c

contacte The correct French spelling is “contact”.

- d

destiné The correct French spelling is “destinée”.

- e

O western wind ... again! The poem was written below the document’s signature but with the sheet turned 180°.

Boismaison

Colette and BR vacationed at a house, The Avenue, owned by Mrs. Agnes Woodhouse and her husband, in the countryside near Ashford Carbonel, Shropshire, in August 1917. They nicknamed the house “Boismaison”. Agnes Woodhouse took in paying guests. Their first visit was idyllic. They returned for other vacations — in 1918 before he entered prison and in April 1919. Their plan to go soon after he got out of prison failed because their relationship faltered for a time. They discussed returning in the summer of 1919 — a booking was even made for 12–19 July — but in the end they didn’t go. See S. Turcon, “Then and Now: Bertie and Colette’s Escapes to the Peak District and Welsh Borderlands”, Russell 34 (2014): 117–30.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.