Brixton Letter 100

BR to Constance Malleson

September 8, 1918

- ALS

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-100

BRACERS 19360

<Brixton Prison>1

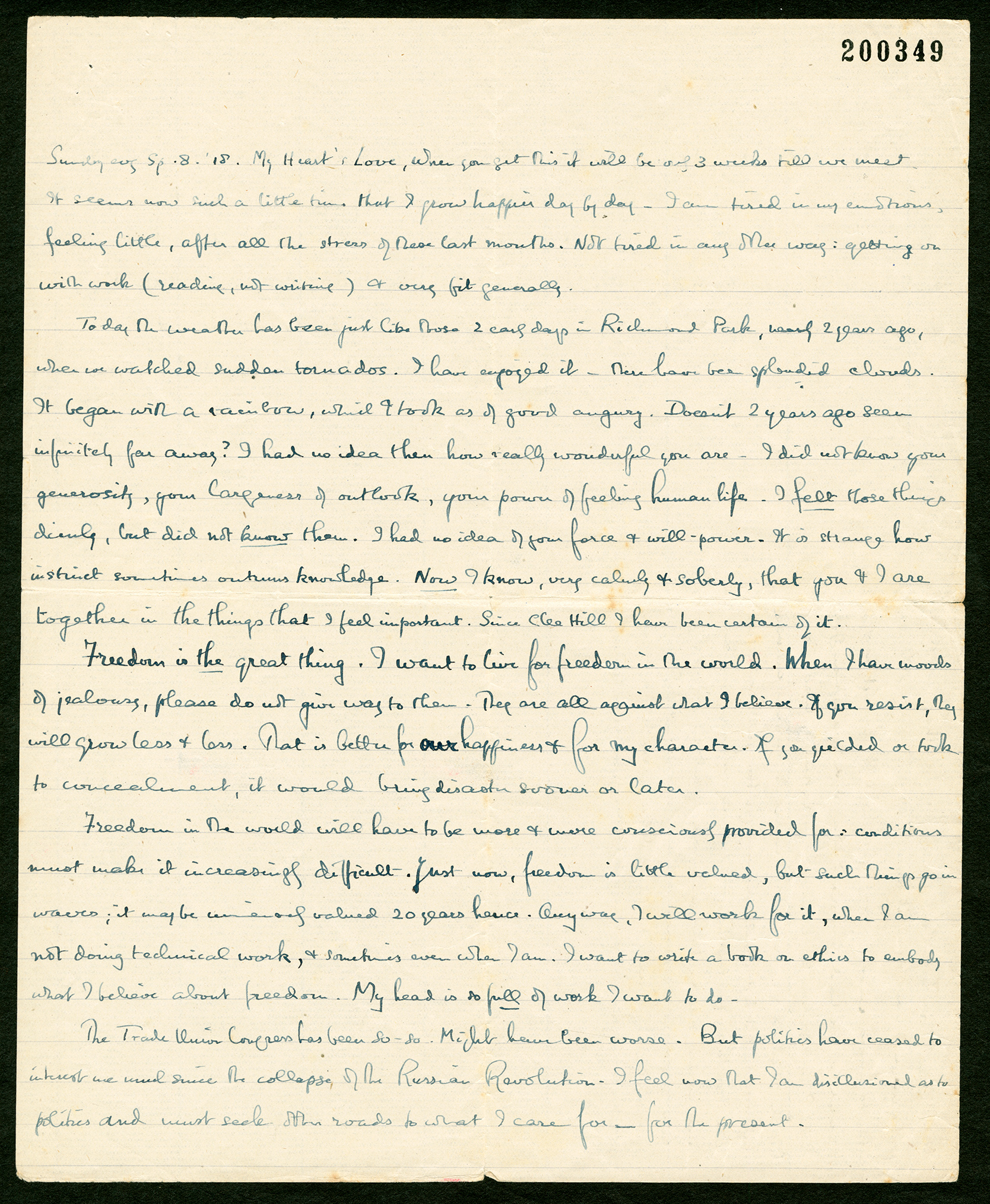

Sunday evg Sp. 8. ’18.

My Heart’s Love, when you get this it will be only 3 weeks till we meet.2 It seems now such a little time that I grow happier day by day. I am tired in my emotions, feeling little, after all the stress of these last months. Not tired in any other way: getting on with work (reading, not writing) and very fit generally.

Today the weather has been just like those 2 early days in Richmond Park, nearly 2 years ago, when we watched sudden tornados.3 I have enjoyed it — there have been splendid clouds. It began with a rainbow, which I took as of good augury. Doesn’t 2 years ago seem infinitely far away? I had no idea then how really wonderful you are. I did not know your generosity, your largeness of outlook, your power of feeling human life. I felt those things dimly, but did not know them. I had no idea of your force and will-power. It is strange how instinct sometimes outruns knowledge. Now I know, very calmly and soberly, that you and I are together in the things that I feel important. Since Clee Hill I have been certain of it.

Freedom is the great thing. I want to live for freedom in the world. When I have moods of jealousy, please do not give way to them. They are all against what I believe. If you resist, they will grow less and less. That is better for our happiness and for my character. If you yielded or took to concealment, it would bring disaster sooner or later.

Freedom in the world will have to be more and more consciously provided for: conditions must make it increasingly difficult. Just now, freedom is little valued, but such things go in waves; it may be immensely valued 20 years hence. Anyway, I will work for it, when I am not doing technical work, and sometimes even when I am. I want to write a book on ethics to embody what I believe about freedom.4 My head is so full of work I want to do.

The Trade Union Congress has been so-so.5 Might have been worse. But politics have ceased to interest me much since the collapse of the Russian Revolution.6 I feel now that I am disillusioned as to politics and must seek other roads to what I care for — for the present.

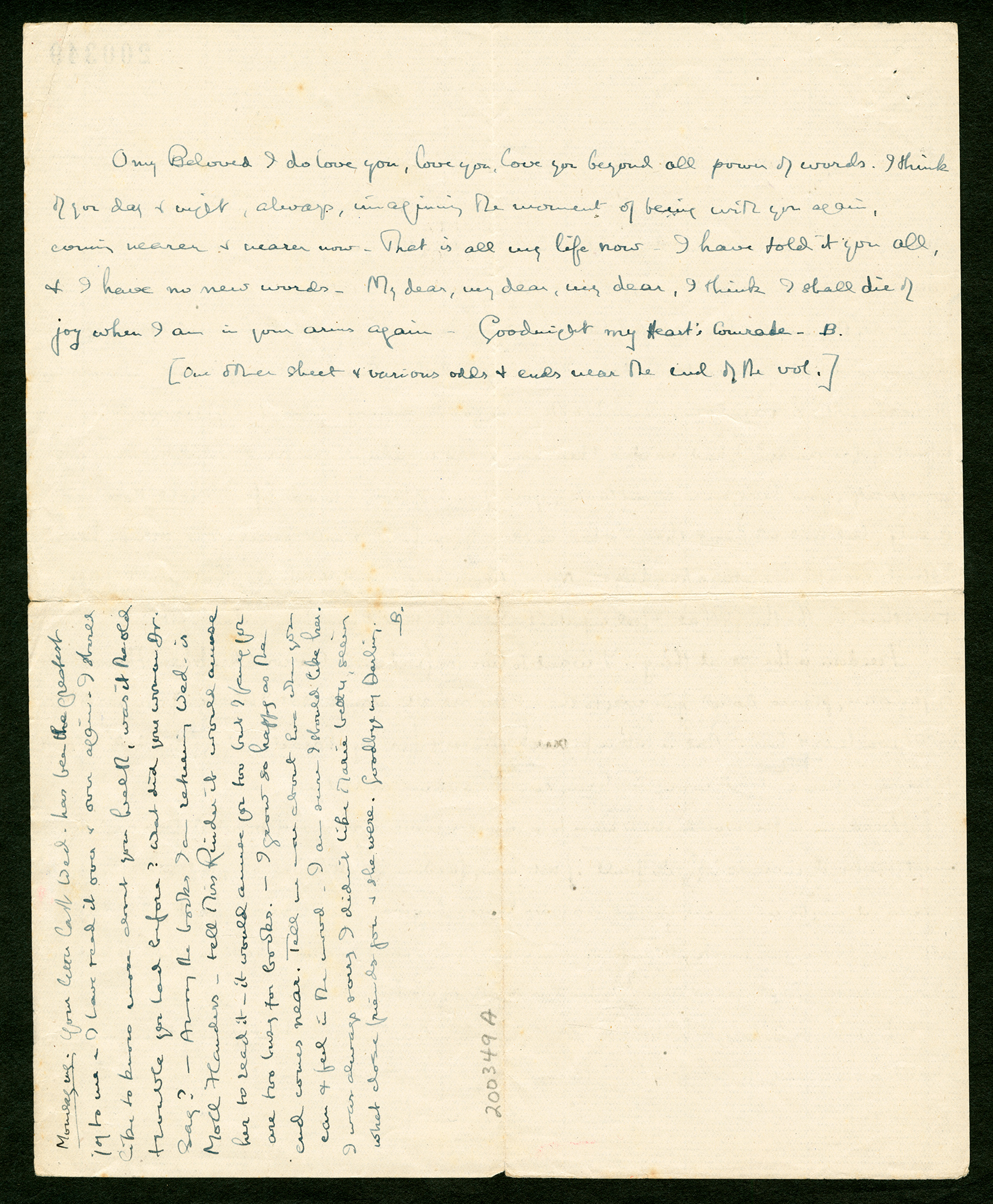

O my Beloved I do love you, love you, love you beyond all power of words. I think of you day and night, always imagining the moment of being with you again, coming nearer and nearer now. That is all my life now. I have told it you all, and I have no new words. My dear, my dear, my dear, I think I shall die of joy when I am in your arms again. Goodnight my Heart’s Comrade

B.

[One other sheet7 and various odds and ends near the end of the volume.]

Monday mg. Your letter last Wed. has been the greatest joy to me. I have read it over and over again. I should like to know more about your health, was it the old trouble8 you had before? What did your woman Dr. say? — Among the books I am returning Wed. is Moll Flanders9 — tell Miss Rinder it would amuse her to read it — it would amuse you too but I fancy you are too busy for books. — I grow so happy as the end comes near. Tell me more about Eve10 when you can and feel in the mood. I am sure I should like her. I was always sorry I didn’t like Marie better, seeing what close friends you and she were. Goodbye my Darling.

B.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the initialled, twice-folded, single-page original in BR’s handwriting in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. The “Monday mg.” passage was written on one of the exposed quarters when the sheet was folded, with the other remaining blank.

- 2

only 3 weeks till we meet In fact, it was less than a week, as BR was granted an earlier than expected remission of his sentence by Sir George Cave, the Home Secretary.

- 3

those 2 early days in Richmond Park ... sudden tornados They spent a memorable day in Richmond Park early in their relationship on 24 October 1916, Colette’s birthday. By “tornados” he surely meant strong winds. BR often recollected this time. In an earlier letter, Letter 81, he remembered “the 2 rain-storms in Richmond Park”, the second outing doubtless being one she agreed to on 31 May 1918 (BRACERS 113133). Colette recollected being in “Richmond Park with storm and rain tearing the giant oaks” in her letter of 31 May 1917 (BRACERS 113133).

- 4

want to write a book on ethics … freedom He did not write a book devoted to theoretical ethics until 1954 (Human Society in Ethics and Politics), but freedom in social relations was a common theme in his post-war books.

- 5

Trade Union Congress has been so-so BR was possibly thinking of the discussion of British war policy and peace terms at this annual conference of organized labour held in Derby from 2 to 7 September 1918. The agreed resolution contained some internationalist language that offered something to the dissenting minority inside the trade union movement, while insisting, to the satisfaction of the patriotic labour majority, that peace negotiations not be started before France and Belgium had been evacuated by the enemy. While BR regarded the upshot of these proceedings as “so-so”, British labour intelligence officials were gratified by the extent of support for the war effort on display at the Trade Union Congress — as revealed, for example, by congratulatory telegrams to Britain’s military commanders and the cheering of encouraging news from the Front (see Trevor Wilson, The Myriad Faces of War: Britain and the Great War, 1914–1918 [Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1986], p. 658).

- 6

collapse of the Russian Revolution BR saw a revolution unravelling in the face of internal chaos and misery, counter-revolutionary resistance, and Allied military intervention. He believed that these convulsions could have been avoided if the Allies had responded to Russian peace feelers after the March 1917 revolution — but before the Bolshevik seizure of power eight months later — by pushing for a negotiated end to the war. He regarded the November revolution as a by-product of this diplomatic failure, but in August 1918 he did not welcome the “collapse” he anticipated. Famously critical of Bolshevik tyranny in later years, BR did not arrive at that hostile appraisal until he travelled to Russia with the British Labour Delegation in 1920. Prior to that visit, he was much more sympathetic to the revolutionary regime and what may be called its political theory (see “Socialism and Liberal Ideals” [1920; see its other titles in B&R C20.14; 32 in Papers 15]). His perspective was similar to that of Britain’s radical Whigs on the French Revolution, who blamed Jacobin extremism on the intemperate reaction of other European powers to events in France after 1789. In February 1918, BR went further, casually excusing the Bolsheviks for dissolving the Constituent Assembly — although this letter of 2 February to Clifford Allen can be read less as an affirmation of patently undemocratic action by Russian revolutionaries than as an expression of disgust with British parliamentary politics and “Cabinet Caesarism” (see Papers 14: xlix, li).

- 7

[One other sheet If extant, it and the “odds and ends” were not found in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives.

- 8

Your letter last Wed. … the old trouble There are edited letters from her written on 2–3 September 1918, that is, on the Monday and Tuesday (BRACERS 113155 and 113156). The first letter does mention her health: “My doctor, by the way, thinks my inside needs attention (same old trouble).” See also Letter 95 and note 4.

- 9

Moll Flanders Daniel Defoe’s The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders (1722). Russell’s remark seems to suggest that this was the first time he had read Defoe’s rollicking picaresque novel, written as the autobiography of the enormously likeable Moll Flanders, thief, pickpocket, and woman of easy virtue. It was not a novel the Victorians liked, but appreciations by members of the Bloomsbury group, especially Virginia Woolf and E.M. Forster, restored it to popularity. In a letter of 1925, BR singled out Defoe’s prose style for praise (J.K. Piercy, ed., Modern Writers at Work [New York: Macmillan, 1930], pp. 11–12).

- 10

Eve Evelyn Walsh Hall appeared both on the stage and in films. Colette described her as a new acquaintance, “not attractive, and perhaps a bit rigid”, although a great admirer of BR (20–21 Aug. 1918; BRACERS 113152). See also note 8 to Letter 78.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Clee Hill

Near Ashford Carbonel, Shropshire, where BR and Colette spent an idyllic summer holiday in August 1917, staying in house named “The Avenue”. BR mentioned the day at Clee Hill in several letters, the last on 8 September 1918 (Letter 100). What exactly happened on that day is not clear in any of his letters. However, in a prison message to BR, Colette remembered that a red fox came and listened to them there (Rinder to BR, 15 June 1918, BRACERS 79614). They also vacationed at The Avenue in March 1918, before BR entered prison.

Clifford Allen

(Reginald) Clifford Allen (1889–1939; Baron Allen of Hurtwood, 1932) was a socialist politician and publicist who joined the Cambridge University Fabian Society while studying at Peterhouse College (1908–11). After graduating he became active in the Independent Labour Party in London and helped establish a short-lived labour newspaper, the Daily Citizen. During the war Allen was an inspiring and effective leader of the C.O. movement as chairman of the No-Conscription Fellowship, which he co-founded with Fenner Brockway in November 1914. Court-martialled and imprisoned three times after his claim for absolute exemption from war service was rejected, Allen became desperately ill during his last spell of incarceration. He was finally released from the second division of Winchester Prison on health grounds in December 1917, but not before contracting the tuberculosis with which he was finally diagnosed in September 1918. He was dogged by ill health for the rest of his life. BR had enormous affection and admiration for Allen (e.g., 68 in Papers 13, 46 in Papers 14), a trusted wartime political associate. From February 1919 until March 1920 he even shared Allen’s Battersea apartment. A close friendship was soured, however, by Allen’s rejection of BR’s unforgiving critique of the Bolshevik regime, which both men witnessed at first hand with the British Labour Delegation to Russia in May 1920 (see Papers 15: 507). Yet Allen was far from revolutionary himself and did not even identify with the left wing of the ILP (which he chaired in the early 1920s). He was elevated to the peerage as a supporter of Ramsay MacDonald’s National Government, an administration despised by virtually the entire labour movement. Although Allen’s old intimacy with BR was never restored after the Russia trip, any lingering estrangement did not inhibit him from enrolling his daughter, Joan Colette (“Polly”) at the Russells’ Beacon Hill School.

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Heart’s Comrade

Colette first called BR her “heart’s comrade” in her letter of 17 November 1916 (BRACERS 112964). On 9 December (BRACERS 112977), she explained: “I want you as comrade as well as lover.” On 9 April 1917 (BRACERS 19145), he reciprocated the sentiment for the first time. In a letter of 1 January 1918 (BRACERS 19260), BR was so upset with her that he could no longer call her “heart’s comrade”. After their relationship was patched up, he wrote on 16 February 1918 (BRACERS 19290): “I do really feel you now again my Heart’s Comrade.” The last time that BR expressed the sentiment in a letter to her was 26 August 1921 (BRACERS 19742).

Home Secretary / Sir George Cave

Sir George Cave (1856–1928; Viscount Cave, 1918), Conservative politician and lawyer, was promoted to Home Secretary (from the Solicitor-General’s office) on the formation of the Lloyd George Coalition in December 1916. His political and legal career peaked in the 1920s as Lord Chancellor in the Conservative administrations led by Andrew Bonar Law and Stanley Baldwin. At the Home Office Cave proved to be something of a scourge of anti-war dissent, being the chief promoter, for example, of the highly contentious Defence of the Realm Regulation 27C (see Letter 51).

Marie Blanche

Marie Blanche (1891–1973) studied at the Academy of Dramatic Arts where she met Colette. She sang as well as acted and had a successful career on the London stage in the 1920s. A photograph of her appeared in The Times, 20 March 1923, p. 16.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.