Brixton Letter 90

BR to Ottoline Morrell

August 31, 1918

- AL

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila TurconCite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, russell-letters.mcmaster.ca

Auto. 2: 93; 102, Papers 14

/brixton-letter-90

BRACERS 131572

<Brixton Prison>1

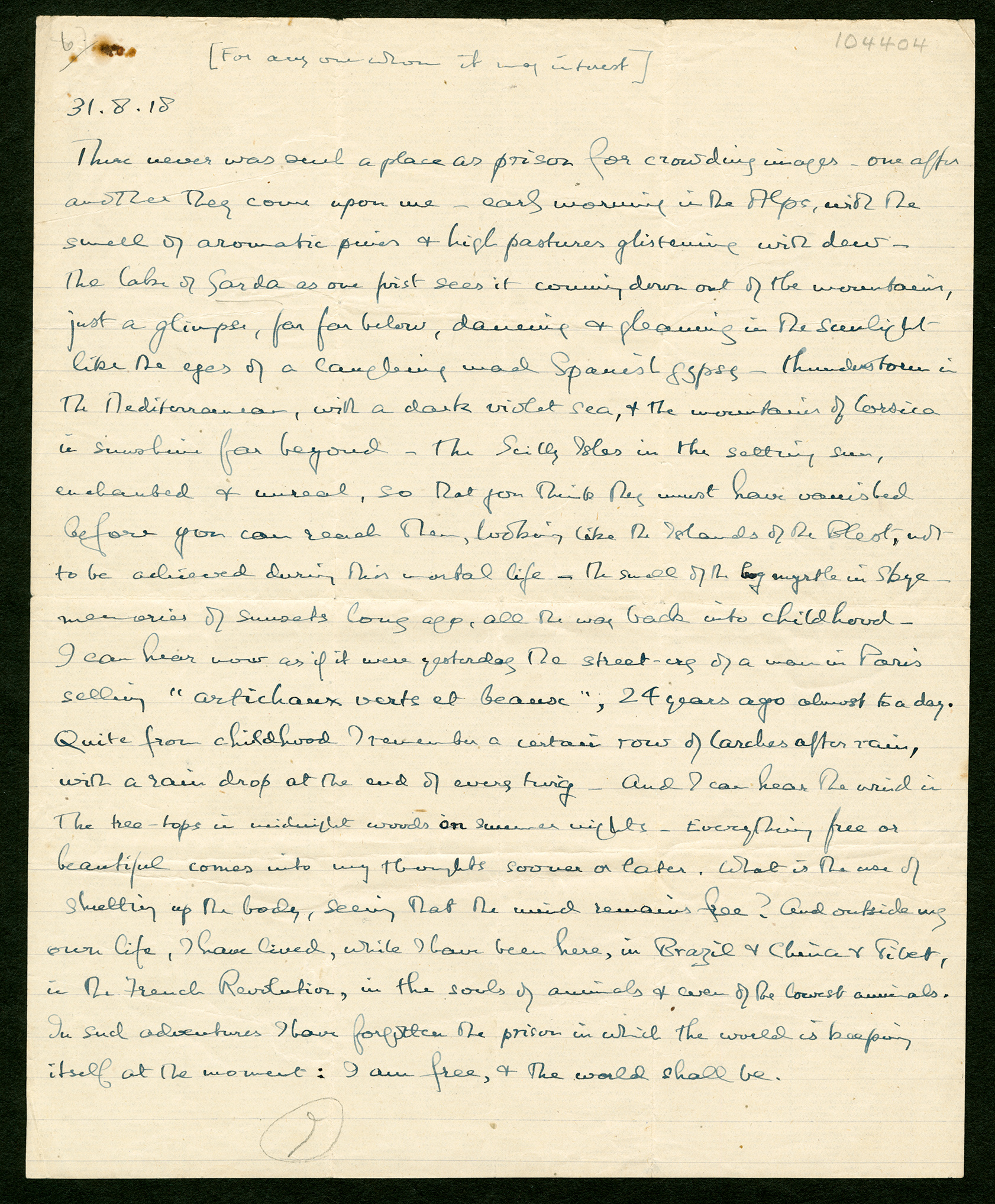

31.8.18

[For any one whom it may interest]

There never was such a place as prison for crowding images — one after another they come upon me — early morning in the Alps, with the smell of aromatic pines and high pastures glistening with dew — the lake of Garda2 as one first sees it coming down out of the mountains, just a glimpse, far far below, dancing and gleaming in the sunlight like the eyes of a laughing mad Spanish gypsy — thunderstorm in the Mediterranean, with a dark violet sea, and the mountains of Corsica in sunshine far beyond — the Scilly Isles in the setting sun, enchanted and unreal, so that you think they must have vanished before you can reach them, looking like the Islands of the Blest, not to be achieved during this mortal life3 — the smell of the bog myrtle in Skye — memories of sunsets long ago, all the way back into childhood. I can hear now as if it were yesterday the street-cry of a man in Paris selling “artichaux verts et beaux”, 24 years ago4 almost to a day. Quite from childhood I remember a certain row of larches after rain, with a rain drop at the end of every twig. And I can hear the wind in the tree-tops in midnight woods on summer nights. Everything free or beautiful comes into my thoughts sooner or later. What is the use of shutting up the body, seeing that the mind remains free? And outside my own life, I have lived, while I have been here, in Brazil and China and Tibet,5 in the French Revolution, in the souls of animals and even of the lowest animals.6 In such adventures I have forgotten the prison in which the world is keeping itself at the moment: I am free, and the world shall be.7

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the unsigned, single-sheet original in BR’s hand in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. The sheet was folded four times. The letter was published in BR’s Autobiography, 2: 93–4, and as 102 in Papers 14.

- 2

lake of Garda BR had long rhapsodized over Lake Garda, in northern Italy, known for its crystal-clear water. He told Ottoline in 1911: “How lovely the journey is from Verona to Milan — the lake of Garda, and the campaniles in the plain” (14 Oct. 1911, BRACERS 17304); and next day, “No, I don’t like lakes, except Garda, which I love” (BRACERS 17306). It was there he met Liese von Hattingberg in August 1913, with whom he had an affair in Rome later that year (Auto. 1: 206).

- 3

Islands of the Blest … this mortal life The three legendary Islands of the Blest (or Fortunate Isles), located at the heart of Elysium, were an earthly paradise reserved for the bravest and most virtuous heroes of Greek mythology.

- 4

man in Paris selling “artichaux verts et beaux”, 24 years ago BR recalled the three months he spent in Paris in the fall of 1894 as an honorary attaché at the British Embassy.

- 5

I have been … Brazil and China and Tibet See Letters 7, 9, 80, 84 and 86.

- 6

animals BR’s prison reading included studies of animal behaviour. While there he read Margaret Floy Washburn, The Animal Mind: a Text-Book of Comparative Psychology (1908); see Papers 8: App. III, “Philosophical Books Read in Prison”.

- 7

I am free, and the world shall be Alan Wood termed this letter “one of the finest testaments to the freedom of the human spirit” (Bertrand Russell: thePassionate Sceptic [London: Allen & Unwin, 1957], p. 116).

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

French Revolution Reading

In Letter 2 (6 May 1918) BR instructed his brother to ask Evelyn Whitehead to “recommend books (especially memoirs) on French Revolution”, and reported that he was already reading “Aulard” — presumably Alphonse Aulard’s Histoire politique de la révolution française (Paris: A. Colin, 1901). In a message to Ottoline sent via Frank ten days later (Letter 5), BR hinted that he was especially interested in the period after August 1792, which he felt was “very like the present day”. On 27 May (Letter 9), he conveyed to Frank his disappointment that Evelyn had not yet procured for him any memoirs of the revolutionary era, and that Eva Kyle had only furnished him with The Principal Speeches of the Statesmen and Orators of the French Revolution, 1789–1795, ed. H. Morse Stephens, 2 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1892). This was “not the sort of book I want, BR complained”, but “an old stager history which I have read before” (in Feb. 1902: “What Shall I Read?”, Papers 1: 365). Fortunately, some of the desired literature reached him shortly afterwards, including The Private Memoirs of Madame Roland, ed. Edward Gilpin Johnson (London: Grant Richards, 1901: see Letter 12) — or else a different edition of the doomed Girondin’s prison writings — and the Memoirs of the Comtesse de Boigne, ed. Charles Nicoullaud, 3 vols. (London: Heinemann, 1907: see Letter 15). In Letter 48, BR told Ottoline that he was “absorbed in a 3-volume Mémoire” of the Comte de Mirabeau. The edition has not been identified, but quotations attributed to the same aristocratic revolutionary in Letter 44 appear in Lettres d’amour de Mirabeau, précédées d’une étude sur Mirabeau par Mario Proth (Paris: Garnier Frères, 1874). Some weeks after writing Letter 11 to Colette as one purportedly from Mirabeau to Sophie de Monier (sic), BR actually read the lovers’ prison correspondence, possibly in Benjamin Gastineau’s edition: Les Amours de Mirabeau et de Sophie de Monnier, suivis des lettres choisies de Mirabeau à Sophie, de lettres inédites de Sophie, et du testament de Mirabeau par Jules Janin (Paris: Chez tous les libraires, 1865). BR’s reading on the French Revolution also included letters from Études révolutionnaires, ed. James Guillaume, 2 vols. (Paris: Stock, 1908–09), the collection he misleadingly cited as the source for two other illicit communications to Colette (Letters 8 and 10). Also of relevance (Letter 57) were Napoleon Bonaparte’s letters to his first wife, Joséphine de Beauharnais, which BR may have read in this well-known English translation edited by Henry Foljambe Hall: Letters to Josephine, 1796–1812 (London: J.M. Dent, 1901). Finally, BR obtained a hostile, cross-channel perspective on the French Revolution and Napoleon from Lord Granville’s Private Correspondence, 1781–1821, ed. Castalia, Countess Granville, 2 vols. (London: J. Murray, 1917: see Letters 40, 41 and 44). Commenting towards the end of his sentence on the mental freedom that he had been able to preserve in Brixton, BR wrote about living “in the French Revolution” among other times and places (Letter 90). His immersion in this tumultuous era may have been deeper still if he perused other works not mentioned in his Brixton letters — which he may well have done. Yet BR’s examination of the French Revolution was not at all programmatic (as intimated perhaps by his preference for personal accounts (diaries and letters in addition to memoirs) — unlike much of his philosophical prison reading. Although his political writings are scattered with allusions to the French Revolution (in which he was interested long before Brixton), BR never produced a major study of it. Just over a year after his imprisonment, however, he did publish a scathing and even profound review of reactionary author Nesta H. Webster’s history of the French Revolution, which certainly drew on his reservoir of knowledge about the period (“The Seamy Side of Revolution”, The Athenaeum, no. 4,665 [26 Sept. 1919]: 943–4; Papers 15: 19). While imprisoned briefly in Brixton for a second time, in September 1961, Russell returned to the era of the French Revolution and Napoleon, “enjoying … immensely” (Letter 105) this biography of Mme. de Staël: J. Christopher Herold, Mistress to an Age: a Life of Madame de Staël (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1959; Russell’s library).

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.