Brixton Letter 86

BR to Constance Malleson

August 28, 1918

- AL

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-86

BRACERS 19352

<Brixton Prison>1

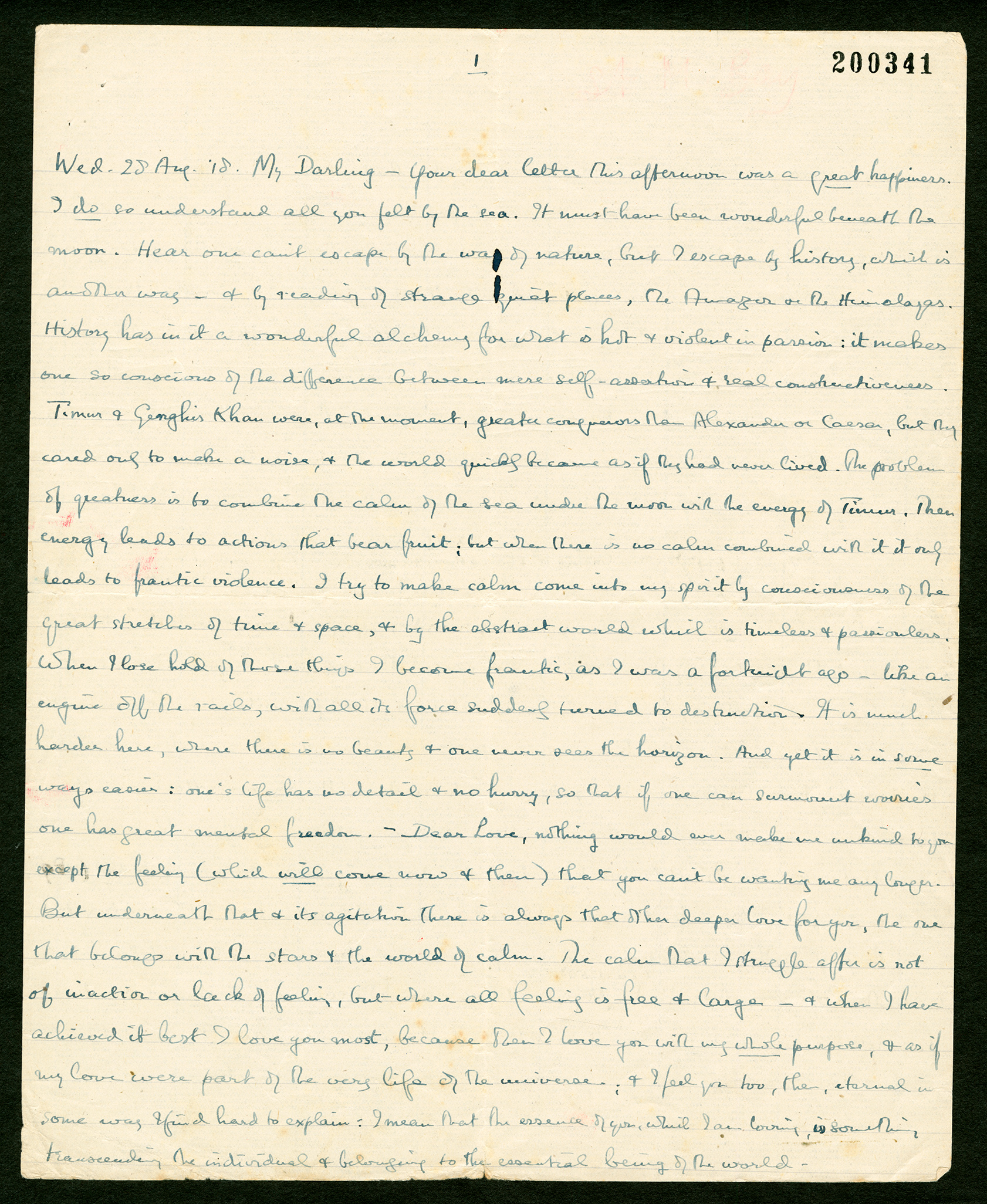

Wed. 28 Aug. ’18.

My Darling

Your dear letter2 this afternoon was a great happiness. I do so understand all you felt by the sea.3 It must have been wonderful beneath the moon. Herea one can’t escape by the way of nature, but I escape by history, which is another way — and by reading of strange quiet places, the Amazon4 or the Himalayas.5 History has in it a wonderful alchemy for what is hot and violent in passion: it makes one so conscious of the difference between mere self-assertion and real constructiveness. Timur and Genghis Khan6 were, at the moment, greater conquerors than Alexander or Caesar,7 but they cared only to make a noise, and the world quickly became as if they had never lived. The problem of greatness is to combine the calm of the sea under the moon with the energy of Timur. Then energy leads to actions that bear fruit; but when there is no calm combined with it it only leads to frantic violence. I try to make calm come into my spirit by consciousness of the great stretches of time and space, and by the abstract world which is timeless and passionless. When I lose hold of those things I become frantic, as I was a fortnight ago — like an engine off the rails, with all its force suddenly turned to destruction. It is much harder here, where there is no beauty and one never sees the horizon. And yet it is in some ways easier: one’s life has no detail and no hurry, so that if one can surmount worries one has great mental freedom. — Dear Love, nothing would ever make me unkind to you except the feeling (which will come now and then) that you can’t be wanting me any longer. But underneath that and its agitation there is always that other deeper love for you, the one that belongs with the stars and the world of calm. The calm that I struggle after is not of inaction or lack of feeling, but where all feeling is free and large — and when I have achieved it best I love you most, because then I love you with my whole purpose, and as if my love were part of the very life of the universe; and I feel you too, then, eternal in some way I find hard to explain: I mean that the essence of you, which I am loving, is something transcending the individual and belonging to the essential being of the world.

I am so glad you told Priscilla8 and she understood. And I am glad to know more about Eve.9 Tell me more about her when you can and feel the impulse.

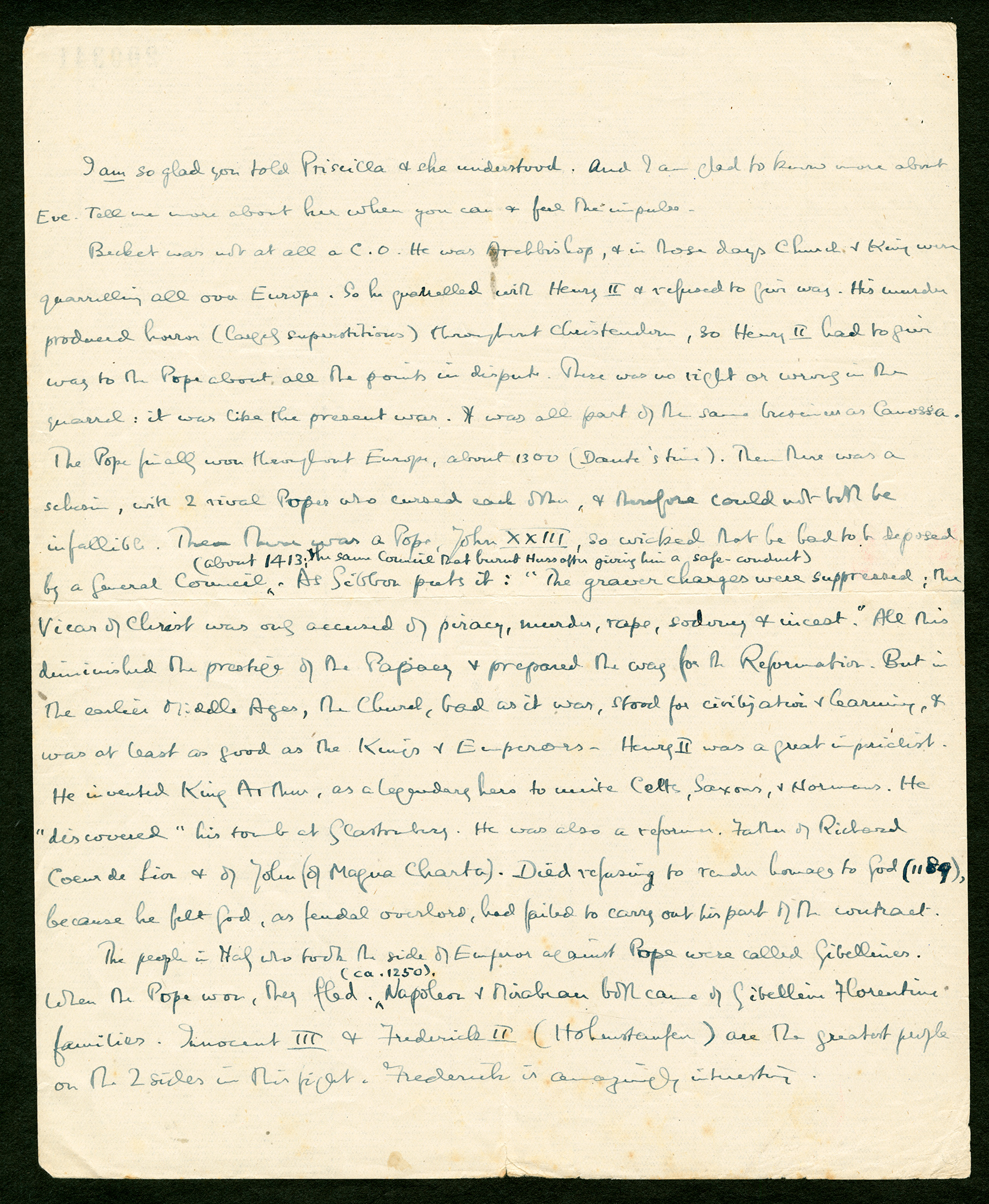

Becket was not at all a C.O. He was Archbishop, and in those days Church and King were quarrelling all over Europe. So he quarrelled with Henry II and refused to give way. His murder10 produced horror (largely superstitious) throughout Christendom, so Henry II had to give way to the Pope11 about all the points in dispute. There was no right or wrong in the quarrel: it was like the present war. It was all part of the same business as Canossa.12 The Pope finally won throughout Europe, about 1300 (Dante’s time).13 Then there was a schism, with 2 rival Popes14 who cursed each other, and therefore could not both be infallible. Then there was a Pope, John XXIII,15 so wicked that he had to be deposed by a General Council (about 1413; the same Council that burnt Huss after giving him a safe-conduct).16, b As Gibbon puts it:17 “The graver charges were suppressed; the Vicar of Christ was only accused of piracy, murder, rape, sodomy and incest.” All this diminished the prestige of the Papacy and prepared the way for the Reformation. But in the earlier Middle Ages, the Church, bad as it was, stood for civilization and learning, and was at least as good as the Kings and Emperors. Henry II was a great imperialist. He invented King Arthur, as a legendary hero to unite Celts, Saxons, and Normans.18 He “discovered” his tomb at Glastonbury.19 He was also a reformer. Father of Richard Coeur de Lion and of John (of Magna Charta).20 Died refusing to render homage to God (1189), because he felt God, as feudal overlord, had failed to carry out his part of the contract.

The people in Italy who took the side of Emperor against Pope were called Gibellines.21, c When the Pope won, they fled. (ca. 1250).d Napoleon and Mirabeau both came of Gibelline Florentine families.22 Innocent III23 and Frederick II24 (Hohenstaufen) are the greatest people on the 2 sides in this fight. Frederick is amazingly interesting.

<on a separate sheet>

“On Paying Calls in August”25

By Cheng Hsiao (A.D. 250).

When I was young, throughout the hot season

There were no carriages driving about the roads.

People shut their doors and lay down in the cool:

Or, if they went out, it was not to pay calls.

Now-a-days — ill-bred, ignorant fellows,

When they feel the heat, make for a friend’s house.

The unfortunate host, when he hears some one coming

Scowls and frowns, but can think of no escape.

“There’s nothing for it but to rise and go to the door”,

And in his comfortable seat he groans and sighs.

The conversation does not end quickly:

Prattling and babbling, what a lot he says!

Only when one is almost dead with fatigue

He asks at last if one isn’t finding him tiring.

(One’s arm is almost in half with continual fanning:

The sweat is pouring down one’s neck in streams.)

Do not say that this is a small matter:

I consider the practice a blot on our social life.

I therefore caution all wise men

That August visitors should not be admitted.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the unsigned, twice-folded, single-sheet original in BR’s handwriting in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. Immediately following the document is a single, twice-folded sheet in BR’s hand with a short paper, “The Single Tax” (101 inPapers 14), on one side and the Chinese poem “On Paying Calls in August” on the verso (document 200342). BR surely sent it to her at or about this time. Papers 14 incorrectly states the “accompanying” letter is dated 28 August “1917”.

- 2

dear letterColette’s letter of 25–27 August 1918 (BRACERS 113153).

- 3

you felt by the seaColette had spent a few days’ holiday with her mother at St. Margaret’s Bay near Dover. She wrote in her letter of 25–27 August: “the windows are wide open to the sound of the sea” (BRACERS 113153).

- 4

AmazonOttoline lent BR H.M. Tomlinson, The Sea and the Jungle (1912) (Ottoline to Tomlinson, 3 June 1918, BRACERS 122079); he also read H.W. Bates, The Naturalist on the River Amazons (1863) (see Letter 9).

- 5

Himalayas BR wrote Gladys Rinder two days earlier: “Tell Bob Trevy I love his book about Thibet” (Letter 84, which also quotes from the book). Robert C. Trevelyan (1872–1951), an old Cambridge friend, had sent him this work by the Japanese Buddhist monk Ekai Kawaguchi: Three Years in Thibet (Benares and London: Theosophical Publishing Society, 1909).

- 6

Timur and Genghis Khan Timur (1336–1405), of Turco-Mongol descent, founded the Timurid Empire (1370–1405) in Central Asia. He married into Genghis Khan’s family. Khan (c.1162–1227) was a Mongolian warrior ruler who unified the tribes of Mongolia. The Mongol Empire lasted rather longer (1206–1368).

- 7

Alexander or Caesar In his short, spectacular reign as Macedonian king after 336 BC, Alexander (356–324 BC) destroyed the powerful Persian Empire and extended Macedonian control over Asia Minor, Syria, Egypt, Persia and even into the Punjab. Of Alexander, BR wrote several decades later: “The effect of Alexander on the imagination of Asia was great and lasting” (HWP, p. 221). Gaius Julius Caesar (100–44 BC), the ruler of Rome, had conquered Gaul (modern day France). He was assassinated, but the changes he set in motion turned the Roman republic into an empire, which lasted until the fifth century in the West and (as Byzantium) as late as the fifteenth in the East.

- 8

glad you told PriscillaColette had written: “Last night, on a sudden impulse, I told Priscilla all about you. So now she knows everything, and understands. I’m so very glad I told her” (BRACERS 113153). Colette was vacationing with her mother, Priscilla.

- 9

more about Eve Colette had already written twice about Evelyn Walsh Hall (on 20 Aug. 1918, BRACERS 113152, and 25 Aug., BRACERS 113153), an actress and recent acquaintance of Colette. Hall was a great admirer of BR. See the note to Letter 78.

- 10

Becket … His murder Thomas à Becket (c.1118–1170), Archbishop of Canterbury, 1162–70, Christian martyr and saint, was murdered in his cathedral on the instructions of Henry II. Colette had visited Canterbury during her holiday, prompting her to ask BR “what sort of person Becket really was and what his attitude would have been if he were alive today” (BRACERS 113153).

- 11

Henry II … give way to the Pope Two years after Becket’s murder, Pope Alexander III (Orlando Bandinelli, c.1105–1181, elected pope 1159) absolved Henry II (1133–1189, ruled from 1154) of any guilt in the Archbishop’s death. In return, England’s first Plantagenet monarch agreed through this Compromise of Avranches (1172) to limit the jurisdiction of civil courts over the clergy and to restore other ecclesiastical powers and privileges. These had been restricted by the Constitutions of Clarendon, enacted by Henry II in 1164.

- 12

Canossa BR later described the situation. In 1077 Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV (1050–1106) “decided to seek absolution from the Pope. In the depth of winter, with his wife and infant son and a few attendants, he crossed the Mont Cenis pass, and presented himself as a suppliant before the castle of Canossa, where the Pope [Gregory VII] was. For three days the Pope kept him waiting, bare-foot and in penitential garb. At last he was admitted. Having expressed penitence and sworn, in future, to follow the Pope’s directions in dealing with his German opponents, he was pardoned and received back into communion” (HWP, pp. 415–16).

- 13

(Dante’s time) Dante, 1265–1321, great Italian poet and one often cited by BR.

- 14

schism, with 2 rival Popes The period from 1378 to 1417 in the Roman Catholic church when there were two, and later three, rival popes, each with his own college of cardinals and administrative offices.

- 15

John XXIII Baldassare Cossa (c.1370–1419) was pope during the Western Schism (1410–1415) and is now officially regarded by the Catholic Church as an antipope.

- 16

Council that burnt Huss … safe-conduct The Council of Constance, 1414–18, settled the problem of too many popes by requiring that all resign. Martin V replaced them. “John Huss” is the anglicized name of Jan Hus (c.1369–1415), a Czech Christian reformer and defender of John Wycliffe (c.1320–1384), his spiritual mentor, against the charge of heresy. It was King Sigismund who had granted Huss the safe-conduct, but he was involved in the Council. BR later called the Council’s proceedings against the pope “creditable”, but maintained his view that, in disregarding the safe-conduct, the treatment of Huss was not (HWP, p. 483).

- 17

Gibbon puts itThe History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1776–88; Russell’s library), 6: 605. There’s a tick beside the passage. BR quoted it correctly from memory, except for “graver” where Gibbon wrote “most scandalous”.

- 18

Celts, Saxons, and Normans The Celts were the people living in Britain at the time of the Roman conquest. The Saxons appeared around the 5th century AD from Northern Europe. The Normans were from Normandy and conquered Britain in 1066.

- 19

invented King Arthur … tomb at Glastonbury Henry II patently failed if he cultivated the Arthurian legend in order to stabilize his kingdom, for his rule was hampered not only by Church–State conflict, but also Welsh uprisings and rebellious family members. According to a medieval account as questionable as accounts of the ancient British king himself, Henry was informed about the location of Arthur’s grave by an old bard. Glastonbury Abbey henceforth became an important pilgrimage destination, with both the monks and the Plantagenet dynasty maintaining a vested interest in the emerging cult of Arthur. Despite doubts about the authenticity of the supposed burial site (and the inscribed cross which adorned it), archaeological evidence from Glastonbury confirms that there was settlement there during the Arthurian period (c.600 AD).

- 20

Richard Coeur de Lion and of John (of Magna Charta) Richard (1157–1199) ascended the throne on the death of his father in 1189. Richard died with no heirs. His brother John (1166–1216) succeeded him.

- 21

The people in Italy who took the side of Emperor against Pope were called Gibellines. The Ghibellines’ bitter enemies in their protracted struggle to extend the dominion of the Holy Roman Empire were the Guelfs, who eventually secured the papacy’s temporal authority in Florence and elsewhere in the Italian peninsula. These rival medieval factions also corresponded to competing German princely houses — the Ghibellines representing the Hohenstaufens, and the Guelfs, the Dukes of Saxony and Bavaria.

- 22

Napoleon and Mirabeau both came of Gibelline Florentine families. Napoleon’s Ghibelline ancestors were exiled from Florence in the twelfth century and settled in Sarzana, to the northwest, before moving to Corsica in the late-fifteenth century. The Florentine origins of the Comte de Mirabeau are mentioned by the French revolutionary statesman in his memoirs, which BR had been reading in Brixton (see Letter 48). Although the pro-Ghibelline Riquettis (or Arrighettis) supposedly established themselves in Provence after being banished from Florence in the mid-thirteenth century, the family’s medieval genealogy may be spurious (see Justin H. McCarthy, The French Revolution [New York: Harper & Brothers, 1890], pp. 425–33).

- 23

Innocent III Pope Innocent III (1198–1216). BR calls him one of the great men of the thirteenth century and the first “great Pope in whom there was no element of sanctity” (HWP, p. 443). He ordered the great crusade against the Albigenses, he deposed Raymond, Count of Toulouse, and he called for the Germans to depose the Emperor Otto, which they did.

- 24

Frederick II Frederick II (Hohenstaufen) (1194–1250), Holy Roman Emperor (1220–1250), was judged by BR to be “one of the most remarkable rulers known to history” (HWP, p. 443). In 1931, to his future third wife, he wrote that the Emperor Frederick II “has always fascinated me” (BRACERS 20278). (Perhaps it was because of his versatility in many areas, and he was both civilized and brutish.) BR’s interest in Frederick endured for decades. In 1955, upon receiving the Silver Pears trophy, he pointed out that the Pears Encyclopaedia had no entry on Frederick II. That was soon remedied.

- 25

“On Paying Calls in August” Copied from Arthur Waley, A Hundred and Seventy Chinese Poems (London: Constable, 1918; Russell’s library; BR’s presentation copy to Colette, Russell’s library addition [see Letter 78, note 26]), p. 57. The title there is “Satire on Paying Calls in August”. BR spelled “Nowadays” and “someone” in his own way.

Textual Notes

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

Priscilla, Lady Annesley

Priscilla, Lady Annesley (1870–1941), second wife of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl of Annesley (1831–1908) and mother of Lady Constance Malleson. Colette described her mother as “among the most beautiful women of her day” with a love of bright colours and walking (After Ten Years [London: Cape, 1931], pp. 12–14).

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.