Brixton Letter 85

BR to Ottoline Morrell

August 27, 1918

- ALS

- Texas

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-85Auto. 2: 90-1

BRACERS 18689

<Brixton Prison>1

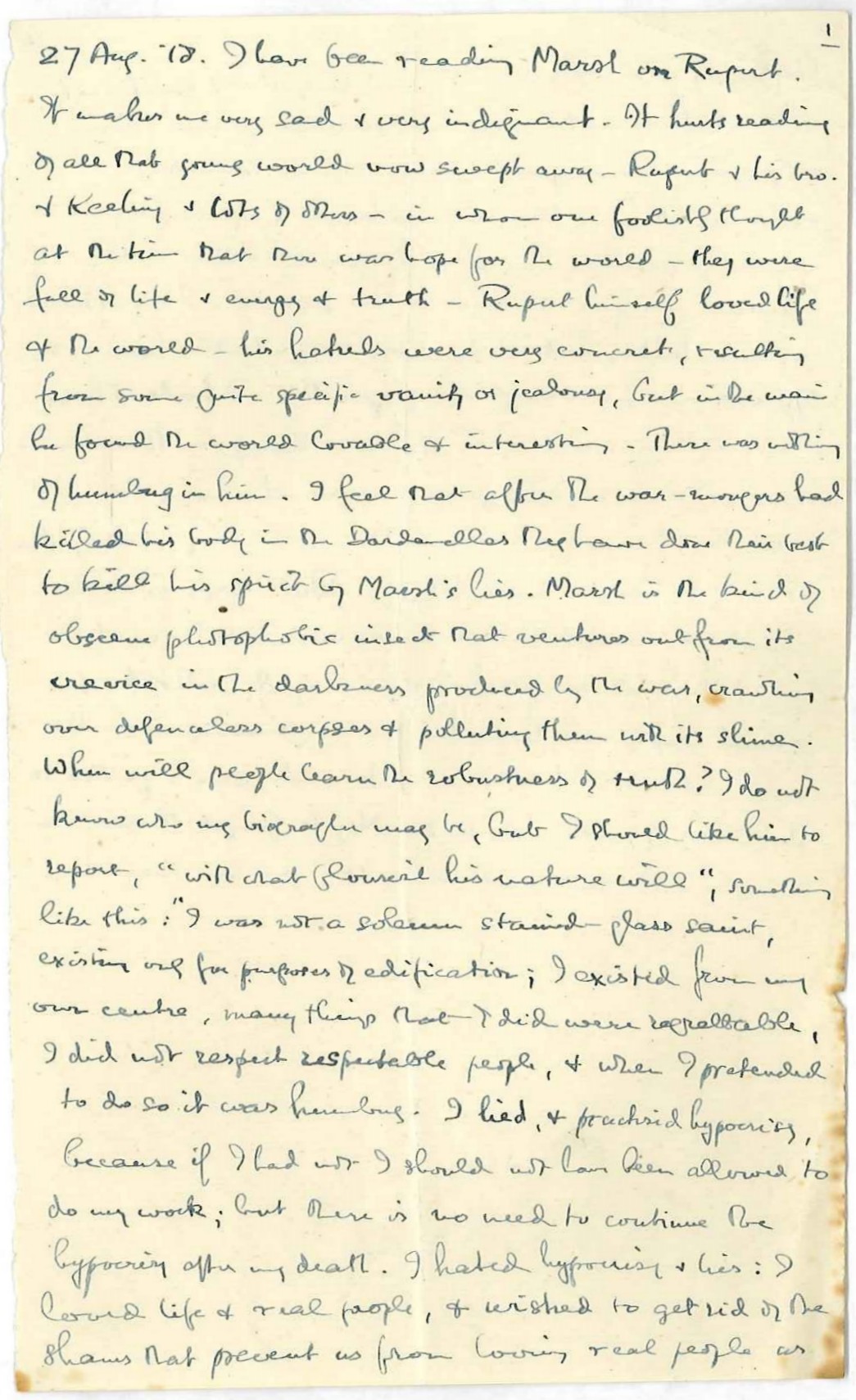

27 Aug. ’18.

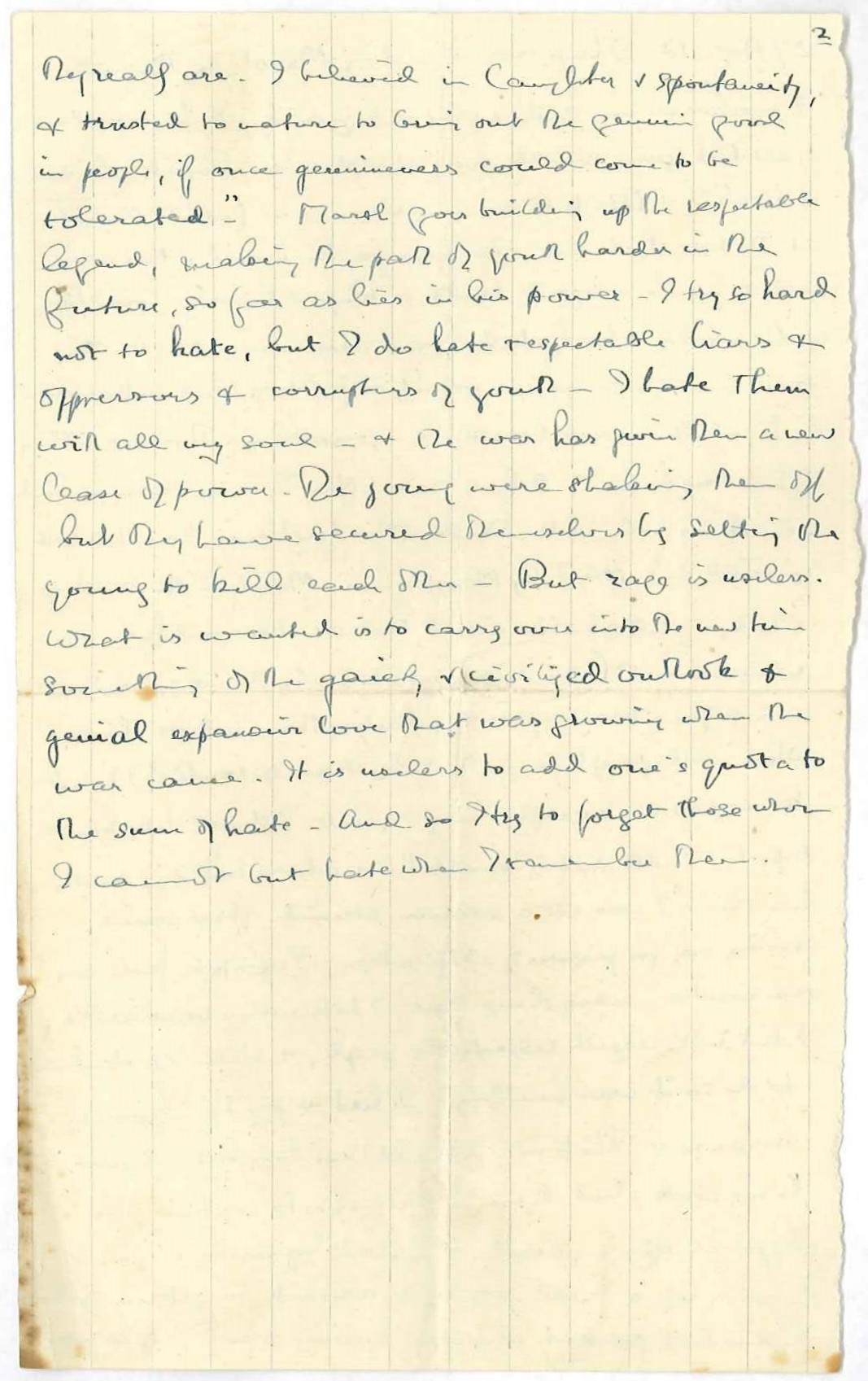

I have been reading Marsh on Rupert.2 It makes me very sad and very indignant. It hurts reading of all that young world now swept away — Rupert and his brother3 and Keeling4 and lots of others — in whom one foolishly thought at the time that there was hope for the world — they were full of life and energy and truth. Rupert himself loved life and the world — his hatreds were very concrete, resulting from some quite specific vanity or jealousy, but in the main he found the world lovable and interesting. There was nothing of humbug in him. I feel that after the war-mongers had killed his body in the Dardanelles they have done their best to kill his spirit by Marsh’s lies.5 Marsh is the kind of obscene photophobic insect that ventures out from its crevice in the darkness produced by the war, crawling over defenceless corpses and polluting them with its slime. When will people learn the robustness of truth? I do not know who my biographer may be, but I should like him to report, “with what flourish his nature will”,6 something like this: “I was not a solemn stained-glass saint, existing only for purposes of edification; I existed from my own centre, many things that I did were regrettable, I did not respect respectable people, and when I pretended to do so it was humbug. I lied, and practised hypocrisy, because if I had not I should not have been allowed to do my work; but there is no need to continue the hypocrisy after my death. I hated hypocrisy and lies: I loved life and real people, and wished to get rid of the shams that prevent us from loving real people as they really are. I believed in laughter and spontaneity, and trusted to nature to bring out the genuine good in people, if once genuineness could come to be tolerated.” Marsh goes building up the respectable legend, making the path of youth harder in the future, so far as lies in his power. I try so hard not to hate, but I do hate respectable liars and oppressors and corrupters of youth — I hate them with all my soul — and the war has given them a new lease of power. The young were shaking them off but they have secured themselves by setting the young to kill each other. But rage is useless. What is wanted is to carry over into the new time something of the gaiety and civilized outlook and genial expansive love that was growing when the war came. It is useless to add one’s quota to the sum of hate. And so I try to forget those whom I cannot but hate when I remember them.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from digital scans of the unsigned, twice-folded, handwritten, half-sheet original in the Morrell papers at the University of Texas at Austin. The letter was published in BR’s Autobiography, 2: 90–1.

- 2

Marsh on Rupert “Afterwards Sir Edward. He had been a close friend of mine when we were undergraduates, but became a civil servant, an admirer of Winston Churchill and then a high Tory.” (BR’s note at Auto. 2: 90n.) Edward Marsh (1872–1953) had edited The Collected Poems of Rupert Brooke; with a Memoir (London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1918). Although the vitriol of BR’s commentary on the book suggests otherwise, his note on the letter indicates that he once prized the friendship of its editor, a fellow Apostle, senior civil servant, literary anthologist, and influential patron of the arts. A lasting breach between the two men opened up over the war, much of which was spent by Marsh acting as Winston Churchill’s private secretary.

- 3

Rupert and his brother In June 1915, less than two months after Rupert Brooke died of sepsis en route to the Gallipoli theatre, his younger brother, (William) Alfred (1891–1915), a lieutenant in the Post Office Rifles (i.e., the 8th Battalion, London Regiment) was killed in action on the Western Front near Loos.

- 4

Keeling As an undergraduate at Trinity College, Frederic Hillersdon (“Ben”) Keeling (1886–1916) founded and became president of the Cambridge University Fabian Society and was a mentor of sorts to other socialist students, including Rupert Brooke. Moving into political journalism, Keeling began writing for The New Statesman when the Fabian weekly started up in 1913. He enlisted in the army the following year but refused a commission and was still serving in the ranks when he was killed on the Somme in August 1916. Not only BR but also G.B. Shaw, H.G. Wells and the Webbs admired Keeling’s talents and mourned his loss (see Samuel Hynes, A War Imagined: the First World War and English Culture [London: Bodley Head, 1990], p. 108).

- 5

Marsh’s lies Marsh’s name and the following sentence in the letter were omitted when it was published in the Autobiography (2: 90).

- 6

“with what flourish his nature will”Hamlet V.ii.140–1.

Annotations by BR

In the late 1940s, when BR was going through his archives, and in the 1950s when he was revising his Autobiography, he would occasionally annotate letters. He did this to sixteen of the Brixton letters. Links to them are gathered here for convenient access to these new texts. In the annotations to the letters they are always followed by “(BR’s note.)”

Letter 2, note 5 happy.

5, note 6 congratulations to G.J.

9, note 28 bit of Girondin history.

12, note 6 friend.

15, note 2 (the letter in general).

20, note 7 G.J.

31, note 3 Dr’s treatment.

40, notes 9, 10 Ld. G.L.G, Lady B’s.

44, note 14 S.S.

48, note 48 Mother Julian’s Bird.

57, notes 13, 16 Ld. Granville’s to Ly. B., bless that Dr. … seat of intellect.

70, note 15 Mrs Scott.

73, note 12 E.S.P. Haynes.

76, note 4 Cave.

85, note 2 Marsh on Rupert.

102, notes 23, 28 Woolley, K. Lonsdale.

General Annotations

Brett note from Auto. 2: 93

Cousens note from Auto. 2: 71

Kyle note with her letters to BR

Rinder note from Auto. 2: 88n.

Silcox note on BRACERS 80365

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Rupert Brooke

Rupert Chawner Brooke (1887–1915), poet and soldier, became a tragic symbol of a generation doomed by war after he died from sepsis en route to the Gallipoli theatre. Although BR had previously expressed a dislike, even loathing, of Brooke in letters to Ottoline, he too placed him in this tragic posthumous light. Rupert “haunts one always”, he wrote Ottoline shortly after the poet’s death in April 1915, and (five months later) “one is made so terribly aware of the waste when one is here [Trinity College]…. Rupert Brooke’s death brought it home to me” (BRACERS 18431, 18435: see also Letter 85). Brooke had become acquainted with BR and members of the Bloomsbury Group in pre-war Cambridge. BR was an examiner of Brooke’s King’s College fellowship dissertation (later published as John Webster and the Elizabethan Drama [1916]), with which he was pleasantly and surprisingly impressed. “It is astonishingly well-written, vigorous, fertile, full of life”, he reported to Ottoline in February 1912 (BRACERS 17447). After the outbreak of war Brooke obtained a commission in a naval reserve unit attached to a military combat battalion; his war poetry captures the patriotic idealism that compelled so many young men to enlist.

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.