Brixton Letter 84

BR to Gladys Rinder

August 26, 1918

- TL(TC)

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-84

BRACERS 79641

<Brixton Prison>1

26th August, 1918.

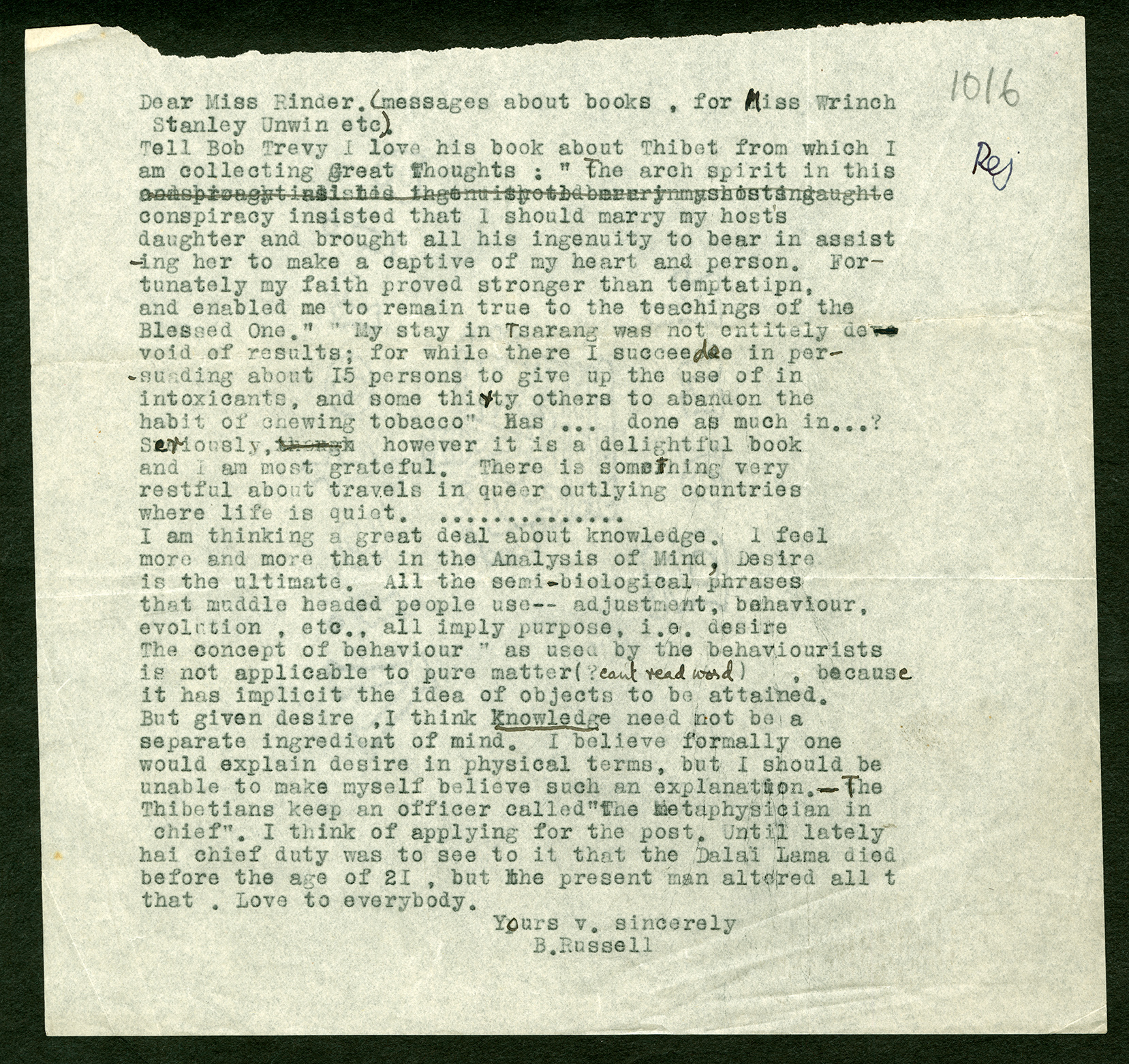

Dear Miss Rinder,

(messages about books, for Miss Wrinch, Stanley Unwin, etc.)

Tell Bob Trevy I love his book about Thibet2 from which I am collecting Great Thoughts: “The arch spirit in this conspiracy insisted that I should marry my host’s daughter and brought all his ingenuity to bear in assisting her to make a captive of my heart and person. Fortunately my faith proved stronger than temptation, and enabled me to remain true to the teachings of the Blessed One.” “My stay in Tsarang was not entirely devoid of results; for while there I succeededa in persuading about 15 persons to give up the use of intoxicants, and some thirty others to abandon the habit of chewing tobacco.” Has … done as much in …?b Seriously, however,c it is a delightful book and I am most grateful. There is something very restful about travels in queer outlying countries where life is quiet. …

I am thinking a great deal about knowledge. I feel more and more that in the Analysis of Mind, Desire3 is the ultimate. All the semi-biological phrases that muddle-headed people use — adjustment, behaviour, evolution, etc., all imply purpose, i.e. desire. The concept of “behaviour” as used by the behaviourists is not applicable to pure matter (? can’t read word)d, because it has implicite the idea of objects to be attained. But given desire, I think Knowledge need not be a separate ingredient of mind. I believe formally one would explain desire in physical terms, but I should be unable to make myself believe such an explanation. — The Thibetans keep an officer called “the metaphysician in chief”. I think of applying for the post. Until lately his chief dutyf was to see to it that the Dalai Lama died before the age of 21, but the present man altered all that.4

Love to everybody.

Yours v. sincerely

B. Russell

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from a typed carbon with corrections in Rinder’s hand, in the Russell Archives at 710.200337. Perhaps it was an “official” letter, but without the original there are no prison initials of approval to confirm it. The earliest extant version is a typed carbon (Letter 84), corrected by Rinder. A circulated, retyped copy is in the Gilbert Murray papers (BRACERS 52373). Its text underwent some regularization. Most readings are taken from the earlier version.

- 2

Bob Trevy ... book about Thibet Ekai Kawaguchi, Three Years in Thibet (Benares and London: Theosophical Publishing Society, 1909). The book had been sent by BR’s old Cambridge friend, the poet and translator Robert Trevelyan (1872–1951). The passages quoted by BR appear on pp. 60 and 63, respectively, but in the original, after “conspiracy” and before “assisting”, the first quotation reads, “was my own instructor Serab, who insisted that I should marry the youngest of my host’s daughters, or rather who brought all his ingenuity to bear upon”.

- 3

Desire BR had previously discussed with Wrinch whether desire or judgment should have explanatory priority (see Letter 51). Wrinch, focussing primarily on logic, favoured judgment, but BR, here as in Letter 5, placed desire at the centre of his theory of mind. In some ways, desire posed the hardest problem for his behaviouristically inspired theory, since it seemed directly to imply an object to the achievement of which an activity was directed, and thus to require an explanation which was teleological rather than purely causal. It is interesting to see BR linking the concepts of adjustment, evolution, and behaviour itself, central concepts in biology and psychology, as all implicitly involving the notion of purpose and thus, in a broad sense, that of desire. However, despite these prescient prison remarks, the theory of desire that BR put forward in Lecture 3 of The Analysis of Mind (1921) did not invoke desire in order to define (purposive) behaviour, but rather attempted to define desire in terms of behaviour-cycles (pp. 65–6). Maybe this was the explanation of desire “in physical terms” that he thought was formally possible, though he would be “unable to make myself believe such an explanation.” If so, one wonders how he brought himself to do so!

His inclusion of “evolution” in the letter among the terms that presuppose purpose deserves separate consideration, for the biological theory of evolution quite explicitly has no such presupposition — as BR well knew. But BR was talking about “the semi-biological phrases that muddle-headed people use”, and “evolution” had certainly been given a teleological gloss by many muddled-headed people from Herbert Spencer to Henri Bergson and George Bernard Shaw. Interestingly, BR went on to include the “concept of ‘behaviour’ as used by the behaviourists”, implying, perhaps, that they, too, are muddle-headed. If so, it was a complaint that he seems to have withdrawn by the time his book was published. - 4

Thibetans … “the metaphysician in chief” … Dalai Lama died before … 21 … all that No such office is mentioned either in the “book about Thibet” by Ekai Kawaguchi, from which BR quotes at the beginning of this letter to Rinder, or in the travelogue of French Jesuit Évariste Huc (Travels in Tartary, Thibet and China [French 1st ed., 1850]) , which, according to Rinder (BRACERS 79625), Robert Trevelyan was also willing to send to Brixton. It is not known whether the latter work ever reached BR there, although he received it as a gift from Ottoline before visiting China in 1920 (see Papers 15: 548–9). BR was clearly amused by the idea of philosophers wielding such temporal power, despite later condemning Tibet’s Buddhist priesthood as “obscurantist, tyrannous, and cruel in the highest degree” (“Has Religion Made Useful Contributions to Civilization?” [1929]; Papers 10: 214). Five years before making this critical judgment, he had again alluded to Tibetan constitutional norms, in commenting upon the gradual separationof politics from western philosophy: “In Tibet ... the second official in the State is called the ‘metaphysician in chief’. Elsewhere philosophy is no longer held in such high esteem” (“Philosophy in the Twentieth Century” [1924]; Papers 9: 451). This more precise description of the position mentioned in Letter 84 suggests that BR may have been thinking of the Panchen Lama (“Great Scholar”), a figure whose standing in Tibetan Buddhism is below only that of the Dalai Lama. But he may have been referring to the office of regent (“Ti Rimpoche”), through which real political authority in Tibet was exercised more or less uninterruptedly between 1815 and 1895, as the 8th to 12th Dalai Lamas all died before reaching the age of 21. BR implicates the Tibetan court in these premature deaths, and foul play may have indeed been responsible in each case. Kawaguchi blamed ruthless and selfish officials fearful of losing rank and privilege “if a wise Dalai Lama is on the throne” (Three Years in Thibet [Benares and London: Theosophical Publishing Society, 1909], p. 318). Lobsang Gyaltsen (b. 1840) was Ti Rimpoche for the 13th Dalai Lama (who died aged 57 in 1933) during the latter’s five-year exile following Britain’s invasion of Tibet in 1904. Gyaltsen also held the title of “Chief Doctor of Divinity and Metaphysics of Tibet” — at least according to Sir Francis Younghusband, the soldier, explorer and mystic who as commander of the British military expedition met this Ti Rimpoche (see Younghusband’s India and Tibet [London: John Murray, 1910], pp. 273–5). BR may have read this work of history and memoir, or at least discussed it with the author, with whom he became quite friendly in pre-war Cambridge and who later (as a senior official at the War Office) secured him an audience with the military officer responsible for upholding the prohibited areas order against him (see Papers 13: 453–4).

Textual Notes

- a

succeeded Mistyped as “succeedee”.

- b

Has … done as much in …? Omissions are in the Murray typescript. The names are omitted in the earliest typed copy.

- c

however, Comma added editorially.

- d

(? can’t read word) In Gladys Rinder’s hand.

- e

implicit The Murray typescript has “implicitly”.

- f

his chief duty The typed carbon reads “hai chief duty”.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Dorothy Wrinch

Dorothy Maud Wrinch (1894–1976), mathematician, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. She studied mathematics and philosophy at Girton College, Cambridge, and came under BR’s influence in her second year when she took his course on mathematical logic. She taught mathematics at University College, London, 1918–21, and then at Oxford, 1922–30. Her first publications were in mathematical logic and philosophy, and during the 1920s she wrote on the philosophy of science. But in the 1930s her interests turned to mathematical biology and crystallography, and in 1935 she moved to the United States on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship and remained there for the rest of her life. Unfortunately, as a biologist she is best known for a long and stubborn controversy with Linus Pauling about the structure of proteins in which he was right and she was wrong. See Marjorie Senechal, I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science (New York: Oxford U. P., 2013). Chapter 7 is devoted to Wrinch’s interactions with BR in Brixton.

Gilbert Murray

Gilbert Murray (1866–1957), distinguished classical scholar and dedicated liberal internationalist. He was Regius Professor of Greek at Oxford, 1908–36, and chair of the League of Nations Union, 1923–36. He and BR enjoyed a long and close friendship that was ruptured temporarily by bitter disagreement over the First World War. After Murray published The Foreign Policy of Sir Edward Grey, 1906–1915, in defence of Britain’s pre-war diplomacy, BR responded with a detailed critique, The Policy of the Entente, 1904–1914: a Reply to Professor Gilbert Murray (37 in Papers 13). Yet Murray still took the lead in campaigning to get BR’s sentence reassigned from the second to the first division and (later) in leading an appeal for professional and financial backing of an academic appointment for BR upon his release (the “fellowship plan”, which looms large in his prison correspondence). BR was still thankful for Murray’s exertions some 40 years later. See his portrait of Murray, “A Fifty-Six Year Friendship”, in Murray, An Unfinished Autobiography with Contributions by His Friends, ed. Jean Smith and Arnold Toynbee (London: Allen & Unwin, 1960).

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

Stanley Unwin

Stanley Unwin (1884–1968; knighted in 1946) became, in the course of a long business career, an influential figure in British publishing and, indeed, the book trade globally — for which he lobbied persistently for the removal of fiscal and bureaucratic impediments to the sale of printed matter (see his The Truth about a Publisher: an Autobiographical Record [London: Allen & Unwin, 1960], pp. 294–304). In 1916 Principles of Social Reconstruction became the first of many BR titles to appear under the imprint of Allen & Unwin, with which his name as an author is most closely associated. Along with G.D.H. Cole, R.H. Tawney and Harold Laski, BR was notable among several writers of the Left on the publishing house’s increasingly impressive list of authors. Unwin himself was a committed pacifist who conscientiously objected to the First World War but chose to serve as a nurse in a Voluntary Aid Detachment. With occasional departures, BR remained with the company for the rest of his life (and posthumously), while Unwin also acted for him as literary agent with book publishers in most overseas markets.

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).