Brixton Letter 79

BR to Constance Malleson

August 22, 1918

- AL

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-79

BRACERS 19349

<Brixton Prison>1

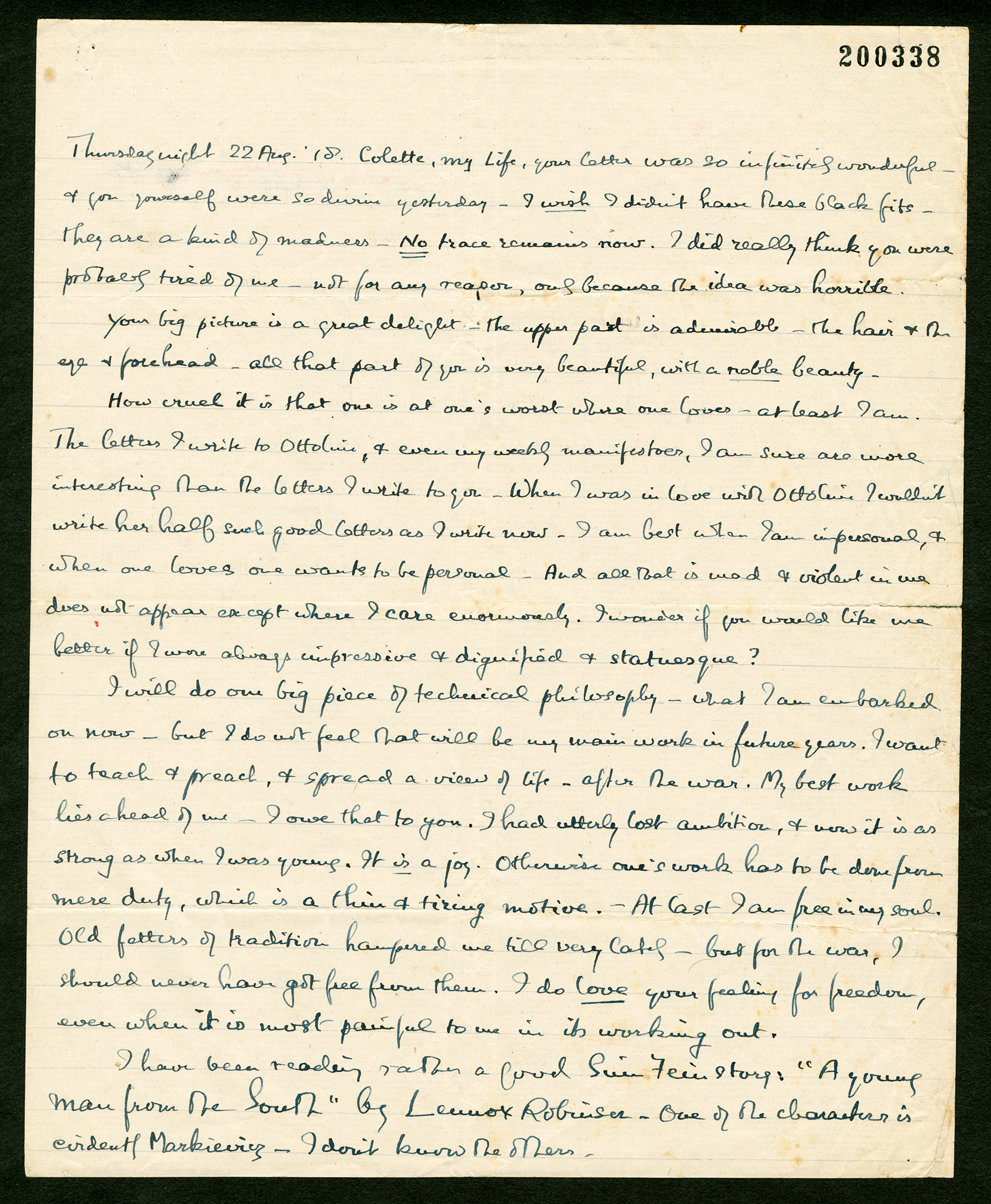

Thursday night 22 Aug. ’18.

Colette, my Life, your letter2 was so infinitely wonderful — and you yourself were so divine yesterday.3 I wish I didn’t have these black fits — they are a kind of madness. No trace remains now. I did really think you were probably tired of me — not for any reason, only because the idea was horrible.

Your big picture is a great delight — the upper part is admirable — the hair and the eye and forehead — all that part of you is very beautiful, with a noble beauty.

How cruel it is that one is at one’s worst where one loves — at least I am. The letters I write to Ottoline, and even my weekly manifestoes,4 I am sure are more interesting than the letters I write to you. When I was in love with Ottoline I couldn’t write her half such good letters as I write now. I am best when I am impersonal,5 and when one loves one wants to be personal. And all that is mad and violent in me does not appear except where I care enormously. I wonder if you would like me better if I were always impressive and dignified and statuesque?

I will do one big piece of technical philosophy6 — what I am embarked on now — but I do not feel that will be my main work in future years. I want to teach and preach, and spread a view of life — after the war. My best work lies ahead of me — I owe that to you. I had utterly lost ambition, and now it is as strong as when I was young. It is a joy. Otherwise one’s work has to be done from mere duty, which is a thin and tiring motive. — At last I am free in my soul. Old fetters of tradition hampered me till very lately — but for the war, I should never have got free from them. I do love your feeling for freedom, even when it is most painful to me in its working out.

I have been reading rather a good Sinn Fein story: A young man from the South by Lennox Robinson.7 One of the characters is evidently Markievicz8 — I don’t know the others.

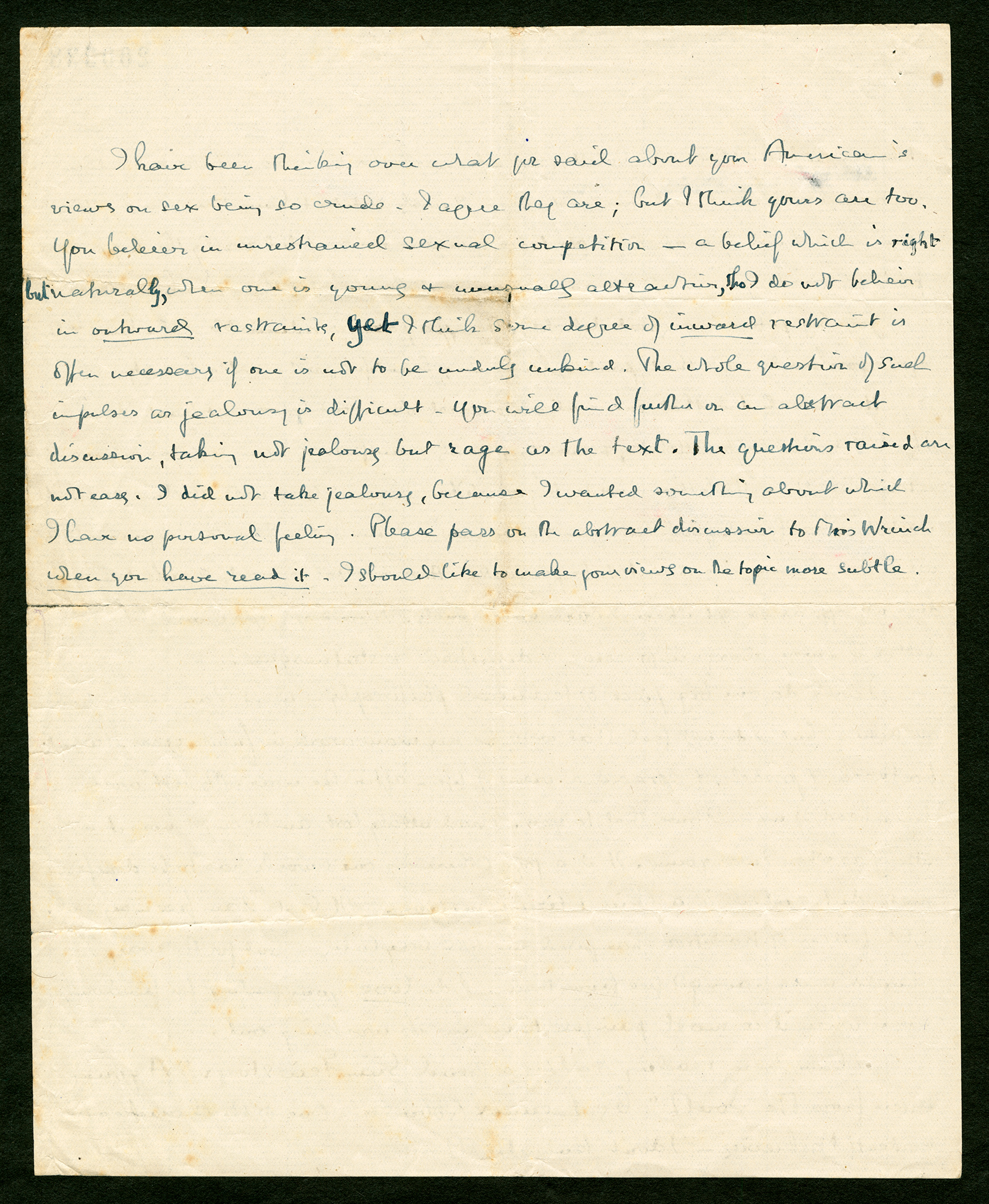

I have been thinking over what you said about your American’s views on sex being so crude.9 I agree they are; but I think yours are too. You believe in unrestrained sexual competition — a belief which is right but naturally, when one is young and unusually attractive, tho’ I do not believe in outward restraints, yet I think some degree of inward restraint is often necessary if one is not to be unduly unkind.a The whole question of such impulses as jealousy is difficult. You will find further on an abstract discussion,10 taking not jealousy but rage as the text. The questions raised are not easy. I did not take jealousy, because I wanted something about which I have no personal feeling. Please pass on the abstract discussion to Miss Wrinch when you have read it. I should like to make your views on the topic more subtle.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the unsigned, thrice-folded single sheet in BR’s hand in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives.

- 2

your letter Possibly her letter of 19 August 1918 (BRACERS 113151), in which she urges him to resist the blackness swallowing him up.

- 3

- 4

my weekly manifestoes Parts of some Brixton letters, rarely identifiable, were extracted and circulated by Rinder to his friends as what he here called “manifestoes”, or (in Letter 81) “public letters”.

- 5

I am best when I am impersonal Impersonality was a quality that BR valued not only in his ethics but also in his philosophical writing. On 22 February 1946 (BRACERS 56417), with his marriage to Peter falling apart, he wrote to his friend Gamel Brenan: “She tries to imprison me in a round of petty personal emotions and is furious when I think about impersonal things. I won’t submit to it any more.”

- 6

one big piece of technical philosophy The big book did not come to fruition because BR did not return to Cambridge after his release (he was invited back in 1919) but became involved in other projects as well as travelling to Russia and China. However, his philosophy of neutral monism, which he was developing at this time, did appear in “On Propositions” (1919) and The Analysis of Mind (1921).

- 7

a good Sinn Fein story ... Robinson Esmé Stuart Lennox Robinson (1886–1958), Irish playwright and theatrical producer, director of Dublin’s famous Abbey Theatre. A Young Man from the South, a novel, was published in 1917.

- 8

evidently Markievicz Constance Gore-Booth (1868–1927), an Irish republican who married a Polish count, Casimir Dunin Markievicz. In December 1918, she was the first woman elected to the British House of Commons but, along with all other Sinn Fein M.P.s, did not take her seat.

- 9

your American’s views on sex being so crudeColette had written in her letter of 20–21 August 1918: “He [Colonel J. Mitchell] is decent, just as I said, but it’s a somewhat crude (?) old-fashioned (?) decency.” She goes on to explain that Mitchell told her he wouldn’t be having an affair with the young woman he was involved with if her husband were still alive, because she would be her husband’s property (BRACERS 113152). Mitchell was in the US army. Colette thought Mitchell may have been chief of staff for Major-General John Biddle, who commanded American troops in the UK in 1918 (After Ten Years [London: Cape, 1931], p. 127).

- 10

find further on an abstract discussion It was “On ‘Bad Passions’”, The Cambridge Magazine 8 (1 Feb. 1919): 359 (B&R C19.04); 19 in Papers 8. The manuscript, titled “Morality and Oppressive Impulses”, begins: “One of the most difficult problems before the moralist and the constructive sociologist is the treatment of impulses recognized as undesirable, such as anger, cruelty, envy, etc. These may be classed together as impulses which essentially (not only accidentally) involve the thwarting of the desires and impulses of others. Such oppressive impulses are often so deep and instinctive that a life in which they are simply thwarted will be felt to be as unsatisfying as (say) a life of celibacy. Moreover, they are liable, if thwarted, to break out with a violence all the greater owing to repression.” He concluded: “The impulsive life can be utterly transformed by physiological means.… [B]y stimulating or retarding the action of various glands, it would seem the character may be utterly changed. Such books as Cannon’s Bodily Changes in Pain, Hunger, Fear and Rage suggest immense possibilities in this direction” (Papers 8: 273, 275).

Textual Notes

- a

a belief which is right … inward restraint … unkind. This awkward sentence replaced “a belief which is natural when one is young and unusually attractive. I do not believe in outward restraints but I think some degree of inward restraint is often necessary if one is not to be unduly unkind.”

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Dorothy Wrinch

Dorothy Maud Wrinch (1894–1976), mathematician, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. She studied mathematics and philosophy at Girton College, Cambridge, and came under BR’s influence in her second year when she took his course on mathematical logic. She taught mathematics at University College, London, 1918–21, and then at Oxford, 1922–30. Her first publications were in mathematical logic and philosophy, and during the 1920s she wrote on the philosophy of science. But in the 1930s her interests turned to mathematical biology and crystallography, and in 1935 she moved to the United States on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship and remained there for the rest of her life. Unfortunately, as a biologist she is best known for a long and stubborn controversy with Linus Pauling about the structure of proteins in which he was right and she was wrong. See Marjorie Senechal, I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science (New York: Oxford U. P., 2013). Chapter 7 is devoted to Wrinch’s interactions with BR in Brixton.

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.