Brixton Letter 78

BR to Constance Malleson

August 21, 1918

- AL

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-78

BRACERS 19348

<Brixton Prison>1

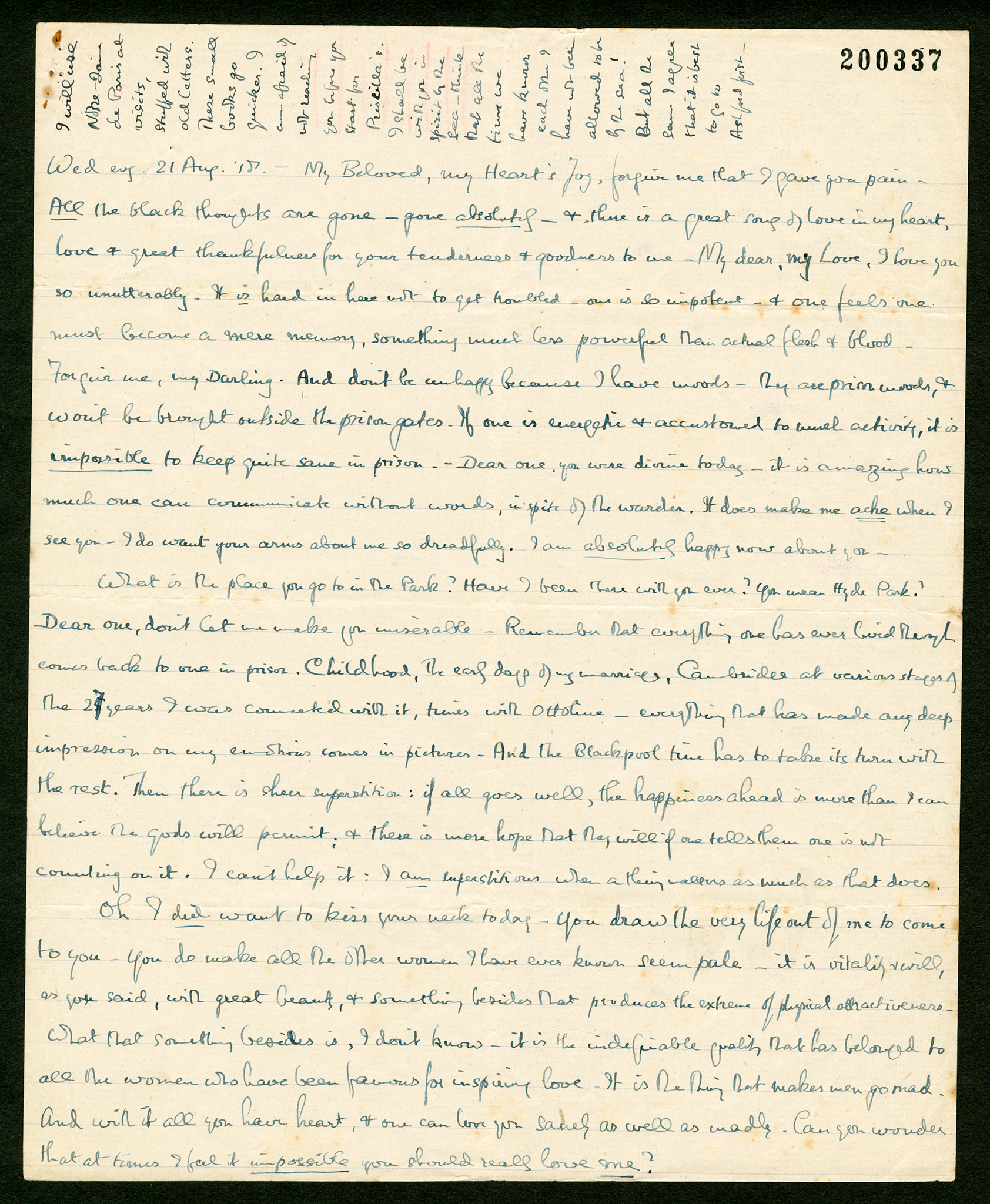

Wed evg 21 Aug. ’18. —

My Beloved, my Heart’s Joy, forgive me that I gave you pain. All the black thoughts are gone — gone absolutely — and there is a great song of love in my heart, love and great thankfulness for your tenderness and goodness to me. My dear, my Love, I love you so unutterably. It is hard in here not to get troubled — one is so impotent — and one feels one must become a mere memory, something much less powerful than actual flesh and blood. Forgive me, my Darling. And don’t be unhappy because I have moods — they are prison moods, and won’t be brought outside the prison gates. If one is energetic and accustomed to much activity, it is impossible to keep quite sane in prison. — Dear one, you were divine today — it is amazing how much one can communicate without words, in spite of the warder. It does make me ache when I see you — I do want your arms about me so dreadfully. I am absolutely happy now about you.

What is the place you go to in the Park?2 Have I been there with you ever? You mean Hyde Park? Dear one, don’t let me make you miserable. Remember that everything one has ever lived through comes back to one in prison. Childhood, the early days of my marriage, Cambridge at various stages of the 27 years3 I was connected with it, times with Ottoline — everything that has made any deep impression on my emotions comes in pictures. And the Blackpool time4 has to take its turn with the rest. Then there is sheer superstition: if all goes well, the happiness ahead is more than I can believe the gods will permit; and there is more hope that they will if one tells them one is not counting on it. I can’t help it: I am superstitious when a thing matters as much as that does.

Oh I did want to kiss your neck today. You draw the very life out of me to come to you. You do make all the other women I have ever known seem pale — it is vitality and will, as you said, with great beauty, and something besides that produces the extreme of physical attractiveness. What that something besides is, I don’t know — it is the indefinable quality5 that has belonged to all the women who have been famous for inspiring love.6 It is the thing that makes men go mad. And with it all you have heart, and one can love you sanely as well as madly. Can you wonder that at times I feel it impossible you should really love me?

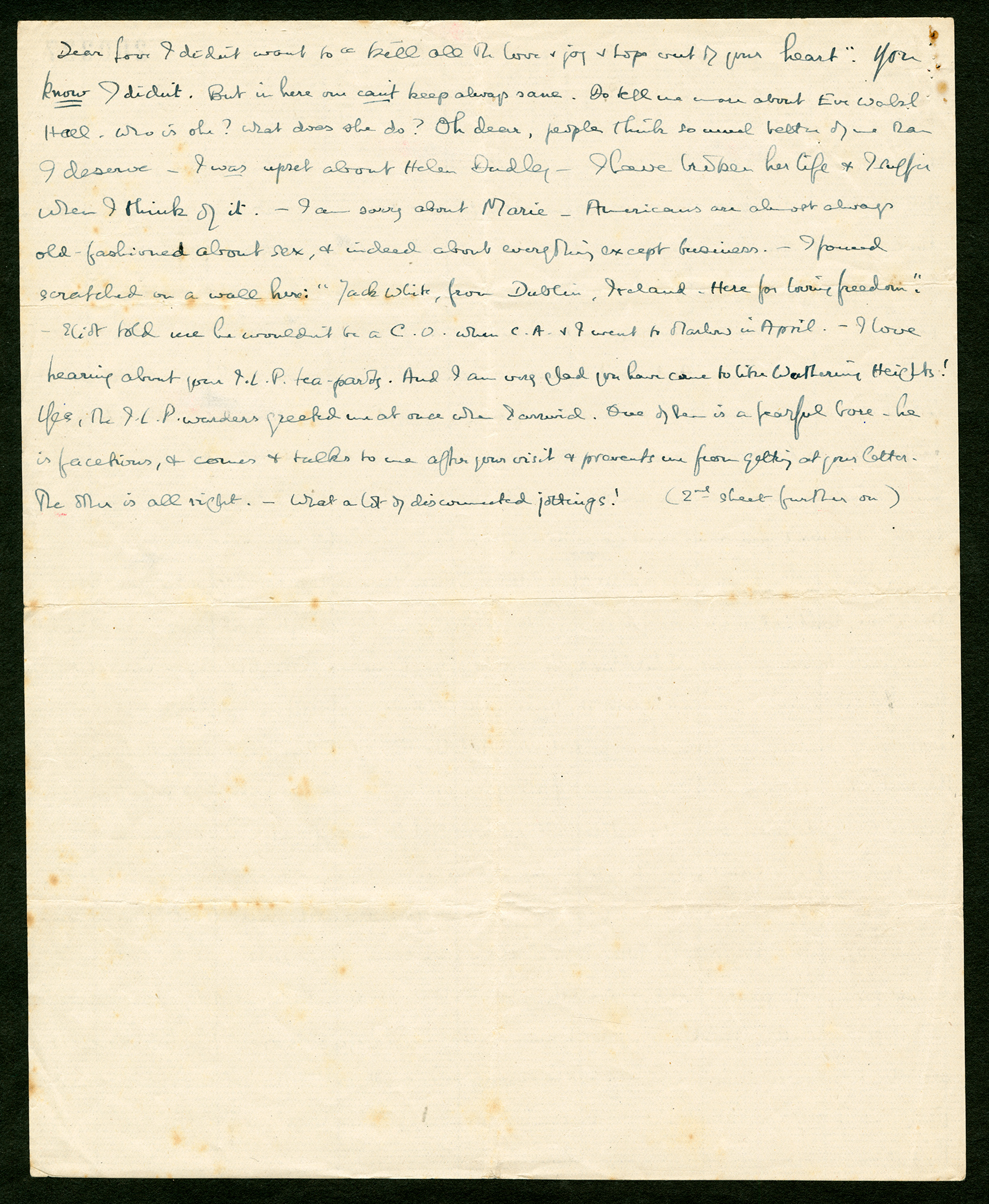

Dear Love I didn’t want to “kill all the love and joy and hope out of your heart”.7 You know I didn’t. But in here one can’t keep always sane. Do tell me more about Eve Walsh Hall.8 Who is she? What does she do? Oh dear, people think so much better of me than I deserve. I was upset about Helen Dudley9 — I have broken her life and I suffer when I think of it. — I am sorry about Marie.10 Americans are almost always old-fashioned about sex, and indeed about everything except business. — I found scratched on a wall here: “Jack White,11 from Dublin, Ireland. Here for loving freedom.” — Eliot told me he wouldn’t be a C.O.12 when C.A. and I went to Marlow13 in April. — I love hearing about your I.L.P. tea-party.14 And I am very glad you have come to like Wuthering Heights!15 Yes, the I.L.P. warders greeted me16 at once when I arrived. One of them is a fearful bore — he is facetious, and comes and talks to me after your visit and prevents me from getting at your letter. The other is all right. — What a lot of disconnected jottings! (2nd sheet further on)

I will use Notre-Dame de Paris at visits, stuffed with old letters.17 These small books go quicker.18 I am afraid of not reaching you before you start for Priscilla’s.19 I shall be with you in spirit by the sea — think that all the time we have known each other I have not been allowed to be by the sea!20 But all the same I agree that it is best to go to Ashford first.a

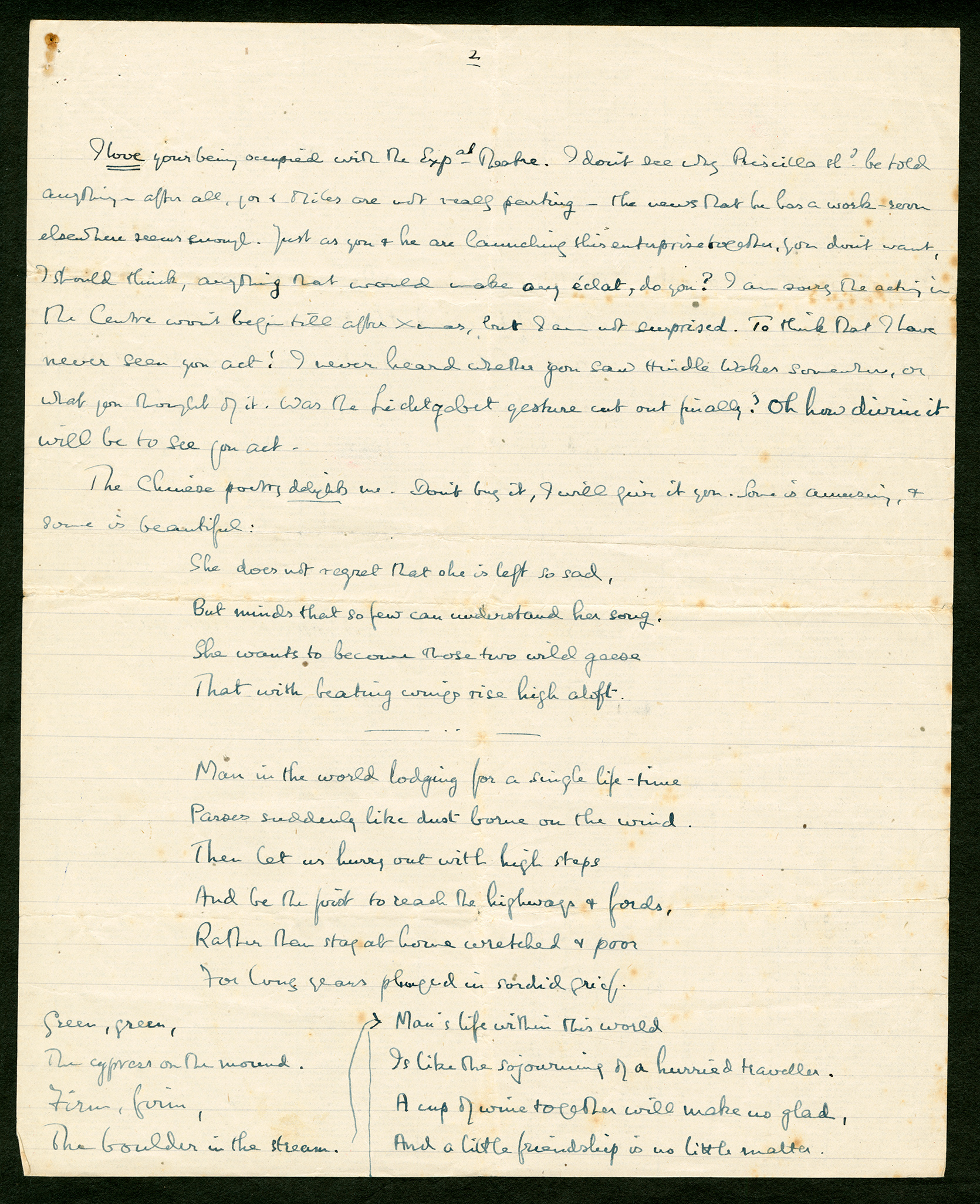

I love your being occupied with the Expal. Theatre. I don’t see why Priscilla should be told anything21 — after all, you and Miles are not really parting22 — the news that he has a work-room elsewhere seems enough. Just as you and he are launching this enterprise together, you don’t want, I should think, anything that would make any éclat, do you? I am sorry the acting in the Centre23 won’t begin till after Xmas, but I am not surprised. To think that I have never seen you act! I never heard whether you saw Hindle Wakes24 somewhere, or what you thought of it. Was the Lichtgebet gesture25 cut out finally? Oh how divine it will be to see you act.

The Chinese poetry delights me. Don’t buy it, I will give it you.26 Some is amusing, and some is beautiful:

She does not regret that she is left so sad,

But minds that so few can understand her song.

She wants to become those two wild geese

That with beating wings rise high aloft.27

_________ .. _________

Man in the world lodging for a single life-time

Passes suddenly like dust borne on the wind.

Then let us hurry out with high steps

And be the first to reach the highways and fords,

Rather than stay at home wretched and poor

For long years plunged in sordid grief.28

Green, green,

The cypress on the mound.

Firm, firm,

The boulder in the stream.

Man’s life within this world

Is like the sojourning of a hurried traveller.

A cup of wine together will make us glad,

And a little friendship is no little matter.29

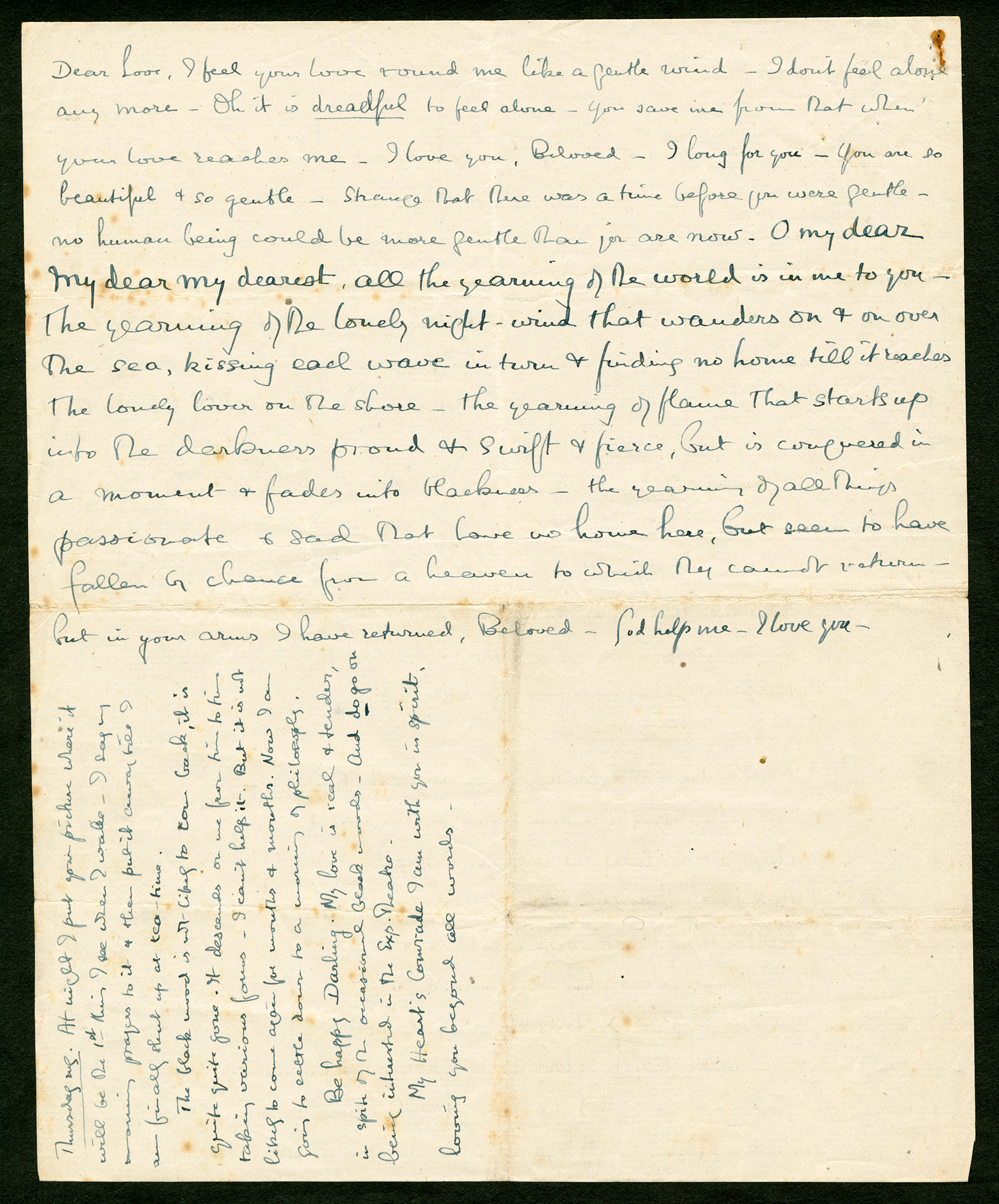

Dear Love, I feel your love round me like a gentle wind. I don’t feel alone any more. Oh it is dreadful to feel alone — You save me from that when your love reaches me. I love you, Beloved — I long for you. You are so beautiful and so gentle. Strange that there was a time before you were gentle — no human being could be more gentle than you are now. O my dear my dear my dearest, all the yearning of the world is in me to you — the yearning of the lonely night-wind that wanders on and on over the sea, kissing each wave in turn and finding no home till it reaches the lonely lover on the shore — the yearning of flame that starts up into the darkness proud and swift and fierce, but is conquered in a moment and fades into blackness — the yearning of all things passionate and sad that have no home here, but seem to have fallen by chance from a heaven to which they cannot return — but in your arms I have returned, Beloved. God help me — I love you.

Thursday mg. At night I put your picture where it will be the 1st thing I see when I wake. I say my morning prayers to it and then put it away till I am finally shut up at tea-time.

The black mood is not likely to come back, it is quite quite gone. It descends on me from time to time taking various forms. I can’t help it. But it is not likely to come again for months and months. Now I am going to settle down to a morning of philosophy.

Be happy Darling. My love is real and tender, in spite of the occasional black moods. And do go on being interested in the Exp. Theatre.

My Heart’s Comrade I am with you in spirit, loving you beyond all words.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the unsigned, foliated, thrice-folded sheets in BR’s hand in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. The sheets were smuggled out in separate locations in the camouflage book used for the occasion. BR added the “Thursday mg” portion of the letter by turning sheet 2 sideways and writing across a blank quarter of the sheet. Folded three times, the sheet concealed this quarter from view.

- 2

place you go to in the ParkColette’s letter of 19 August begins: “In the Park. Always when I’m deeply miserable I come and sit here, in this same place, praying dumbly to these same trees, this red brick, these stones. Why invent a God? Stones do just as well” (BRACERS 113151).

- 3

27 years I.e., from 1889, when BR won a Minor Scholarship to Trinity, to 1916, when he was deprived of his lectureship. He corrected the number from 25.

- 4

Blackpool time The film Hindle Wakes was shot in and near Blackpool in September 1917. BR became very jealous of Colette’s affair with her director, Maurice Elvey, and this jealousy caused a serious rift with her.

- 5

indefinable quality BR, much later, again described his ideal woman for man: “The women for whom men feel a life-long passion, and who rouse the sleeping poet that exists in most of us, have in them something rare and exceptional, something irreplaceable and unique, something that the lover feels to be important, as life and death, the sea and the stars, are important” (“What Makes a Woman a Fascinator?”, Vogue, 104, no. 8 [1 Nov. 1944]: 130).

- 6

all the women who have been famous for inspiring love It is unknown whom BR had in mind at the time of writing the present letter. However, in 1954 he gave a speech on obscenity and other sex-related matters in which he quoted a paragraph on particular lovers well known to history or literature (Papers 28: 459; BR’s source was A.C. Kinsey et al., Sexual Behavior in the Human Female [Philadelphia and London: W.B. Saunders, 1953], p. 13). In addition, Dante’s albeit “purely spiritual affection” for Beatrice might be mentioned (SLBR 1: #47, to Alys Pearsall Smith, 12 Sept. 1894). Not all of Kinsey’s examples may be suitable, but some, at least, of these women (and girls) seem to be whom BR had in mind.

- 7

“kill all the love and joy and hope out of your heart” BR was quoting from Colette’s letter of 19 August (BRACERS 113151), in which she asked him “why have you let blackness swallow you up now — ”.

- 8

tell me more about Eve Walsh HallColette had recently met Hall, an actress. Colette described her as a new acquaintance, not attractive and perhaps a bit rigid although a great admirer of BR. Colette had agreed to spend an evening with her at her St. John’s Wood flat (20–21 Aug. 1918; BRACERS 113152). In response to BR’s question, Colette added that Hall had been married but was living alone (25 Aug.; BRACERS 113153). Evelyn Walsh Hall appeared both on the stage (including Broadway) and in films.

- 9

Helen Dudley An American from Chicago with whom BR became involved during his 1914 trip to the United States. She followed him back to London, was rebuffed by him, and ended up renting his Bury Street flat in late 1916 or early 1917. In May 1918 she sublet it to Clare Annesley, Colette’s sister.

- 10

sorry about MarieColette had written that Marie Blanche had vanished. “I knew her three whole years before I knew you, we were such friends, and now she’s vanished. Sad” (20–21 Aug. 1918; BRACERS 113152). She was not, as the context might suggest, an American.

- 11

scratched on a wall here: “Jack White James Robert (“Jack”) White (1879–1946). Colette had written: “Jack White looked in the other day, taking himself as seriously as ever: a drama (historical) in 5 very long acts” (20–21 Aug. 1918; BRACERS 113152). White had been imprisoned at Brixton in 1916 for attempting to organize a strike of miners in South Wales in protest of the execution of James Connolly (1868–1916), one of fifteen Irish republicans shot by firing squad in May 1916 for leading the Easter Rising.

- 12

Eliot told me he wouldn’t be a C.O.Eliot did so on BR’s visit to their Marlow house with Clifford Allen (see Letter 24, note 2). On 30 July 1918 Britain and the United States ratified a convention authorizing the conscription of each other’s resident alien nationals. But Eliot could still pre-empt a British call-up by enlisting in the American forces, in which the service of married men had been temporarily deferred. In a letter of 17 August 1918 (BRACERS 46932), Rinder wrote that Eliot intended “to register in the American Army, ask for exemption as a married man, and in the meantime if possible get a post in the Intelligence Department or some other branch of the Army more suited to his capacities than general service.” At BR’s prompting (Letter 81), Colette also approached the American army officer mentioned in Letter 79 (to whom she had been introduced by her mother), with a view to his interceding on Eliot’s behalf. On 11 September (BRACERS 113158), she reported that Eliot had met this Colonel J. Mitchell that morning in Russell Chambers, but it is not clear what, if anything, resulted from this meeting. Early in August Eliot was passed medically fit by the US navy, in which he served very briefly after being called up in the final weeks of the war.

- 13

Marlow The Eliots rented a cottage at 31 West Street in the village of Marlow, Bucks., on 5 December 1917. BR had a financial obligation with regard to the rental, and he contributed furniture as well. See Letter 103, note 12.

- 14

your I.L.P. tea-partyColette had hosted fifteen Independent Labour Party branch secretaries to tea and was expecting another fifteen the next day. She had to break off her letter to BR because she “was trying to calculate how many sandwiches 15 secretaries will consume before and after the meeting.” She resumed the letter, writing that “the evening went off really well” (BRACERS 113152).

- 15

glad you have come to like Wuthering Heights!Colette was writing a dramatization of Wuthering Heights. The sentence that remains in her edited letter of 20–21 August is hardly a ringing endorsement: “I plod on with ‘W.H.’ and shall have lots to say about it (another time)” (BRACERS 113152).

- 16

I.L.P. warders greeted meColette had noted that two members of the Brixton branch of the Independent Labour Party were warders at the prison (20–21 Aug. 1918; BRACERS 113152).

- 17

Notre-Dame de Paris at visits, stuffed with old letters Presumably the novel by Victor Hugo, first published in 1831 and more widely known to English readers as The Hunchback of Notre-Dame.

- 18

small books go quicker Doubtless BR meant that the Post Office delivered them quicker.

- 19

before you start for Priscilla’sPriscilla had invited her for a weekend by the sea.

- 20

I have not been allowed to be by the sea! Since 1 September 1916 BR had been banned from all prohibited areas, including the sea coasts, by the government.

- 21

I don’t see why Priscilla should be told anything I.e., about BR and Colette’s relationship.

- 22

you and Miles are not really parting In fact, BR had been pushing for Colette to leave Miles. Miles moved briefly into the Studio and by September had gone to Glastonbury for several weeks to produce a play. Colette by then was living in BR’s Bury Street flat.

- 23

the acting in the Centre Nothing about “Centre” is extant in “Letters to Bertrand Russell from Constance Malleson, 1916–1969” (typescript in RA). In fact, at the beginning of the following month, Colette wrote that she was learning three roles (3 Sept. 1918, BRACERS 113156).

- 24

never heard whether you saw Hindle Wakes It is not surprising that Colette had not mentioned whether she had seen the film, since her affair with the film’s director, Maurice Elvey, had strained her relationship with BR to the breaking point.

- 25

Lichtgebet gesture BR may be alluding to a painting called “Lichtgebet”, by Hugo Höppner (a.k.a. Fidus), of a nude figure standing on a high cliff with arms upraised in praise to the light. How it related to the film (which has not survived) is unknown.

- 26

Chinese poetry … I will give it you A few days later (25 Aug. 1918), Colette wrote that she expected BR had seen “Waley’s exquisite Chinese poems in The Nation.” (Only one, “Crossing an Old Battlefield at Night”, was translated by Waley [Nation 23 (17 Aug. 1918): 526].) She especially liked “Green, green” (BRACERS 113153). The three poems in the present letter were quoted from Arthur Waley’s A Hundred and Seventy Chinese Poems, published in July 1918. BR copied out parts of numbers 3, 4, and 5, all contained within “Seventeen Old Poems” (pp. 39–48). There are copies of this book in both Russell’s library (2nd ed.) and from Colette (1st ed., a Russell library “addition”). Her copy was inscribed in BR’s hand: “Colette / September 14, 1918 / Bury Street.” Much later, in 1958, Colette added: “On the morning that Russell came out of Brixton Prison, he brought me this book ... I therefore think it must be the copy sent to him in prison by Waley.”

- 27

She does not … rise high aloft. Arthur Waley, A Hundred and Seventy Chinese Poems (London: Constable, 1918), p. 42.

- 28

Man in the world … in sordid grief. Waley, p. 41. BR omitted the quote marks around the five lines.

- 29

Green, green … no little matter. Waley, p. 40. BR omitted “lived” after “life” in the fifth line.

Textual Notes

- a

I will use Notre-Dame de Paris … go to Ashford first. The paragraph was written sideways in the top margin of the recto of sheet 1.

Boismaison

Colette and BR vacationed at a house, The Avenue, owned by Mrs. Agnes Woodhouse and her husband, in the countryside near Ashford Carbonel, Shropshire, in August 1917. They nicknamed the house “Boismaison”. Agnes Woodhouse took in paying guests. Their first visit was idyllic. They returned for other vacations — in 1918 before he entered prison and in April 1919. Their plan to go soon after he got out of prison failed because their relationship faltered for a time. They discussed returning in the summer of 1919 — a booking was even made for 12–19 July — but in the end they didn’t go. See S. Turcon, “Then and Now: Bertie and Colette’s Escapes to the Peak District and Welsh Borderlands”, Russell 34 (2014): 117–30.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Clifford Allen

(Reginald) Clifford Allen (1889–1939; Baron Allen of Hurtwood, 1932) was a socialist politician and publicist who joined the Cambridge University Fabian Society while studying at Peterhouse College (1908–11). After graduating he became active in the Independent Labour Party in London and helped establish a short-lived labour newspaper, the Daily Citizen. During the war Allen was an inspiring and effective leader of the C.O. movement as chairman of the No-Conscription Fellowship, which he co-founded with Fenner Brockway in November 1914. Court-martialled and imprisoned three times after his claim for absolute exemption from war service was rejected, Allen became desperately ill during his last spell of incarceration. He was finally released from the second division of Winchester Prison on health grounds in December 1917, but not before contracting the tuberculosis with which he was finally diagnosed in September 1918. He was dogged by ill health for the rest of his life. BR had enormous affection and admiration for Allen (e.g., 68 in Papers 13, 46 in Papers 14), a trusted wartime political associate. From February 1919 until March 1920 he even shared Allen’s Battersea apartment. A close friendship was soured, however, by Allen’s rejection of BR’s unforgiving critique of the Bolshevik regime, which both men witnessed at first hand with the British Labour Delegation to Russia in May 1920 (see Papers 15: 507). Yet Allen was far from revolutionary himself and did not even identify with the left wing of the ILP (which he chaired in the early 1920s). He was elevated to the peerage as a supporter of Ramsay MacDonald’s National Government, an administration despised by virtually the entire labour movement. Although Allen’s old intimacy with BR was never restored after the Russia trip, any lingering estrangement did not inhibit him from enrolling his daughter, Joan Colette (“Polly”) at the Russells’ Beacon Hill School.

Experimental Theatre

Colette first mentioned that she and Miles were trying to start an Experimental Theatre in a letter of 24 June 1918 (BRACERS 113135), indicating that Miles would earn a tiny income from it. About a month later, she wrote that Elizabeth Russell had subscribed generously to the Theatre and that £700 had been raised, but hundreds still had to be found (BRACERS 113146). A few days later she wrote that Captain Stephen Gordon, a north-country lawyer working for the government, was to be the honorary treasurer, noting that he had “put most of the drive into the whole thing” (BRACERS 113147). During August Colette was happy with her involvement with the Theatre (Letter 68). John Galsworthy came to tea to discuss the project (c.14 Aug., BRACERS 113149). On 2 September she listed the members of the Theatre committee as “Desmond <MacCarthy>, Massingham, Galsworthy, and Dennis (Bradley)” (BRACERS 113155). The following day she wrote that she was learning three parts (BRACERS 113156). In her memoirs, Colette wrote about the “Experimental Little Theatre” but dated it 1919 (After Ten Years [London: Cape, 1931], pp. 129–30). An “artistic” theatre did get founded in 1920 in Hampstead, and John Galsworthy was connected to that venture, The Everyman Theatre — he was part of a reading committee which chose the works to be performed (The Times, 9 Sept. 1919, p. 8). The Everyman Theatre was under the direction of Norman MacDermott. In his book Everymania (London: Society for Theatre Research, 1975), he noted that he met Miles in the summer of 1918: they rented a store in Bloomsbury, had a cabinetmaker build sets, and put on plays with actors “bored with West-End theatres” (p. 10). It is likely that the Everyman Theatre was an out-growth of the Experimental Theatre.

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Heart’s Comrade

Colette first called BR her “heart’s comrade” in her letter of 17 November 1916 (BRACERS 112964). On 9 December (BRACERS 112977), she explained: “I want you as comrade as well as lover.” On 9 April 1917 (BRACERS 19145), he reciprocated the sentiment for the first time. In a letter of 1 January 1918 (BRACERS 19260), BR was so upset with her that he could no longer call her “heart’s comrade”. After their relationship was patched up, he wrote on 16 February 1918 (BRACERS 19290): “I do really feel you now again my Heart’s Comrade.” The last time that BR expressed the sentiment in a letter to her was 26 August 1921 (BRACERS 19742).

Marie Blanche

Marie Blanche (1891–1973) studied at the Academy of Dramatic Arts where she met Colette. She sang as well as acted and had a successful career on the London stage in the 1920s. A photograph of her appeared in The Times, 20 March 1923, p. 16.

Maurice Elvey

Maurice Elvey (1887–1967) was a prolific film director (of silent pictures especially) and enjoyed a very successful career in that industry lasting many decades. Born William Seward Folkard into a working-class family, Elvey changed his name around 1910, when he was acting. He directed his first film, The Fallen Idol, in 1913. By 1917, when he directed Colette in Hindle Wakes, he had married for a second time — to a sculptor, Florence Hill Clarke — his first marriage having ended in divorce. Elvey and Colette had an affair during the filming of Hindle Wakes, beginning in September 1917, which caused BR great anguish. In addition to his feeling of jealousy during his imprisonment, BR was worried over the rumour that Elvey was carrying a dangerous sexually transmitted disease. (See BR, “My First Fifty Years”, RA1 210.007050–fos. 127b, 128, and Monk, 2: 507). Colette later maintained that Elvey cleared himself (“Letters to Bertrand Russell from Constance Malleson, 1916–1969”, p. 154, typescript, RA). BR removed the allegation from the Autobiography as published (see 2: 37), but he remained fearful. After Elvey’s long-lost wartime film about the life of Lloyd George was rediscovered and restored in the 1990s, it premiered to considerable acclaim (see Letter 87, note 12).

Miles Malleson

Miles Malleson (1888–1969), actor and playwright, was born in Croydon, Surrey, the son of Edmund and Myrrha Malleson. He married his first wife, a fellow actor, Lady Constance Annesley (stage name, Colette O’Niel), in 1915. They had met at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts). Their marriage was an “open” one. In 1914 Miles enlisted in the City of London Fusiliers and was sent to Malta. He became ill and was discharged, unfit for further service. He became active in the No-Conscription Fellowship and wrote anti-war stage plays as well as a pamphlet, Cranks and Commonsense (1916). In the 1930s he began to write for the screen and act in films, in which he became a very well-known character actor, as well as continuing his stage career at the Old Vic in London. He married three times: his second marriage was to Joan Billson, a physician (married 1923, divorced 1940), with whom he had two children; his third wife was Tatiana Lieven, an actress (married 1946). He died in London in March 1969.

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

Priscilla, Lady Annesley

Priscilla, Lady Annesley (1870–1941), second wife of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl of Annesley (1831–1908) and mother of Lady Constance Malleson. Colette described her mother as “among the most beautiful women of her day” with a love of bright colours and walking (After Ten Years [London: Cape, 1931], pp. 12–14).

Prohibited areas

On 17 July 1918 (BRACERS 75814) General George Cockerill, Director of Special Intelligence at the War Office, notified Frank Russell that constraints on BR’s freedom of movement, imposed almost two years before, had been lifted as of 11 July. Since 1 September 1916, BR had been banned under Defence of the Realm Regulation 14 from visiting any of Britain’s “prohibited areas” without the express permission of a “competent military authority”. The extra-judicial action was taken partly in lieu of prosecuting BR for a second time under the Defence of the Realm Act, on this occasion over an anti-war speech delivered in Cardiff on 6 July 1916 (63 in Papers 13). (Britain’s Director of Public Prosecutions was confident that a conviction could be secured but concerned lest BR should again exploit the trial proceedings for propaganda effect and thereby create “a remedy … worse than the disease” [HO 45/11012/314760/6, National Archives, UK].) Since the exclusion zone covered many centres of war production, BR would be prevented (according to the head of MI5) from spreading “his vicious tenets amongst dockers, miners and transport workers” (quoted in Papers 13: lxiv). But the order also applied to military and naval installations and almost the entire coastline. As a lover of the sea and the seaside, BR chafed under the latter restriction: “I can’t tell you how I long for the SEA”, he told Colette (Letter 75).

Russell Chambers

34 Russell Chambers, Bury Street (since renamed Bury Place), London WC1, BR’s flat since 1911. Helen Dudley rented the flat in late 1916 or early 1917. In May 1918 she sublet it to Clare Annesley. Colette moved in on 9 September 1918 and stayed until June 1919. BR did not give up the lease until December 1923. See S. Turcon, “Russell Chambers, Other London Flats, and Country Homes, 1911–1923”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 150 (Fall 2014): 30–4. “Russell Chambers, Other London Flats, and Country Homes, 1911–1923”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 150 (Fall 2014): 30–4.

T.S. Eliot

The poet and critic Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888–1965) was a student of BR’s at Harvard in 1914. BR had sensed his ability, especially “a certain exquisiteness of appreciation” (to Lucy Donnelly, 11 May 1914; SLBR 1: 491), but did not see a genius in embryo. After Eliot travelled to England later the same year, to study philosophy at Oxford under H.H. Joachim, BR became something of a father figure to the younger man. He also befriended Eliot’s (English) wife, Vivienne, whom he had hastily married in 1915 and with whom BR may have had an affair the following year. BR shared his Bloomsbury apartment (at 34 Russell Chambers) with the couple for more than a year after their marriage, and jointly rented a property with them in Marlow, Bucks. (see Letter 78). He further eased Eliot’s monetary concerns by arranging paid reviewing for him and giving him £3,000 in debentures from which BR was reluctant, on pacifist grounds, to collect the income (Auto. 2: 19). Eliot’s financial security was much improved by obtaining a position at Lloyd’s Bank in 1917, but during BR’s imprisonment he faced uncertainty of a different kind as the shadow of conscription loomed over him (see, e.g., Letter 27). Nine years after the war ended Eliot returned the securities (BRACERS 76480).

The Nation

A political and literary weekly, 1907–21, edited for its entirety by H.W. Massingham before it merged with The Athenaeum and then The New Statesman. BR regularly contributed book reviews, starting in 1907. During his time at Brixton, he published there a book review (14 in Papers 8; mentioned in Letters 4 and 102) and a letter to the editor (Letter 39). In August 1914 The Nation hastily abandoned its longstanding support for British neutrality, rejecting an impassioned defence of this position written by BR on the day that Britain declared war (1 in Papers 13). For the next two years the publication gave its editorial backing (albeit with mounting reservations) to the quest for a decisive Allied victory. At the same time, it consistently upheld civil liberties against the encroachments of the wartime state, and by early 1917 had started calling for a negotiated peace as well. The Nation had recovered its dissenting credentials, but for allegedly “defeatist” coverage of the war was hit with an export embargo imposed in March 1917 by Defence of the Realm Regulation 24B.

The Studio

The accommodation BR and Colette rented on the ground floor at 5 Fitzroy Street, just off Howland Street, London W1. “It had a top light, a gas fire and ring. A water tap and lavatory in the outside passage were shared with a cobbler whose workshop adjoined” (Colette’s annotation at BRACERS 113087). It was ready to occupy in November 1917.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.