Brixton Letter 70

BR to Ottoline Morrell

August 14, 1918

- AL

- Texas

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-70

BRACERS 18686

<Brixton Prison>1

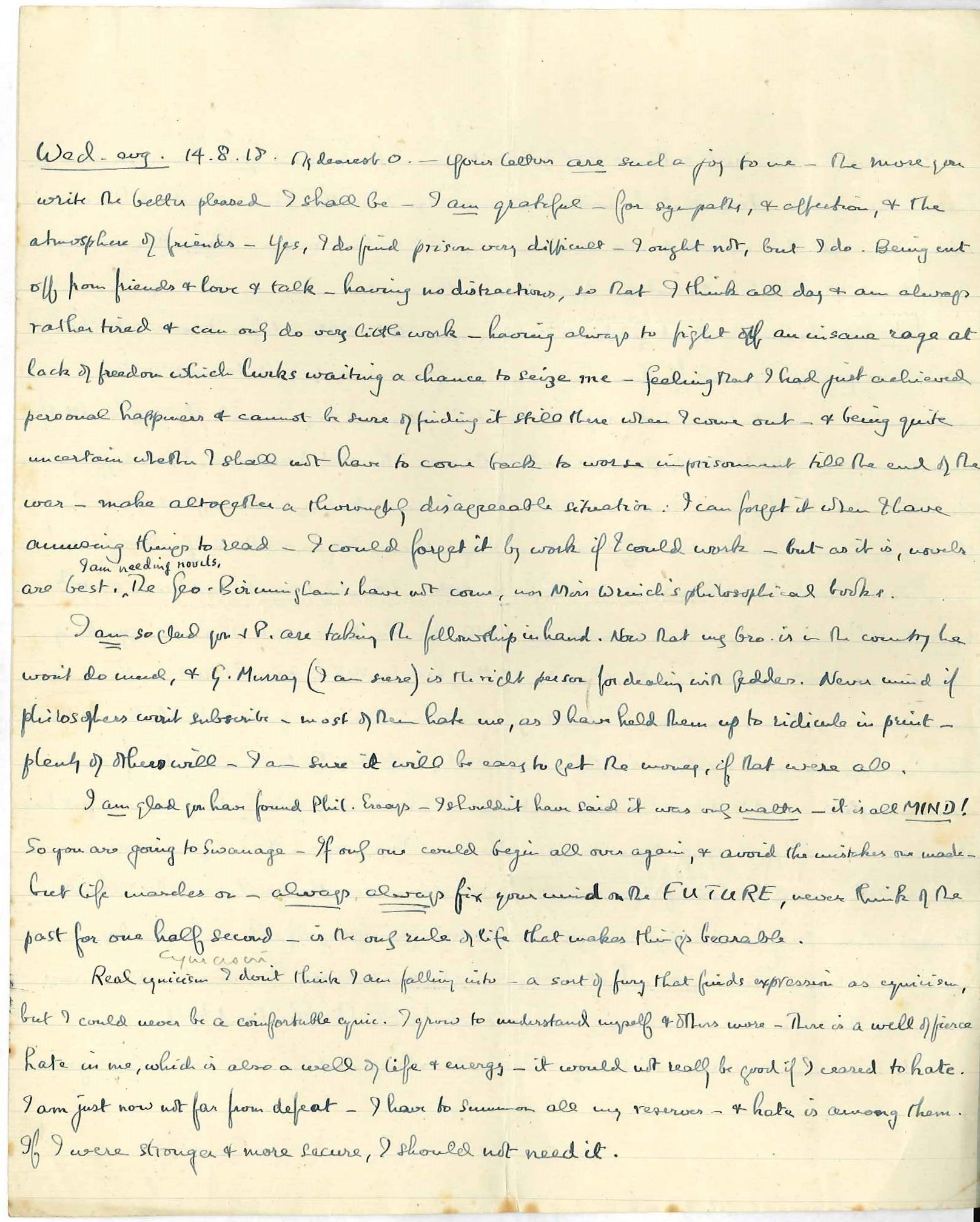

Wed. evg. 14.8.18.

My dearest O.

Your letters are such a joy to me — the more you write the better pleased I shall be. I am grateful — for sympathy, and affection, and the atmosphere of friends. Yes, I do find prison very difficult — I ought not, but I do. Being cut off from friends and love and talk — having no distractions, so that I think all day and am always rather tired and can only do very little work — having always to fight off an insane rage at lack of freedom which lurks waiting a chance to seize me — feeling that I had just achieved personal happiness and cannot be sure of finding it still there when I come out2 — and being quite uncertain whether I shall not have to come back to worse imprisonment till the end of the war3 — make altogether a thoroughly disagreeable situation: I can forget it when I have amusing things to read — I could forget it by work if I could work — but as it is, novels are best. I am needing novels.a The Geo. Birmingham’s have not come,4 nor Miss Wrinch’s philosophical books.5

I am so glad you and P. are taking the fellowship in hand. Now that my brother is in the country he won’t do much, and G. Murray (I am sure) is the right person for dealing with Geddes. Never mind if philosophers won’t subscribe — most of them hate me, as I have held them up to ridicule in print — plenty of others will. I am sure it will be easy to get the money, if that were all.

I am glad you have found Phil. Essays. I shouldn’t have said it was only matter — it is all MIND!6 So you are going to Swanage. If only one could begin all over again,7 and avoid the mistakes one made — but life marches on — always always fix your mind on the FUTURE, never think of the past for one half second — is the only rule of life that makes things bearable.

Real cynicism I don’t think I am falling into — a sort of fury that finds expression as cynicism, but I could never be a comfortable cynic. I grow to understand myself and others more. There is a well of fierce hate in me, which is also a well of life and energy — it would not really be good if I ceased to hate. I am just now not far from defeat — I have to summon all my reserves — and hate is among them. If I were stronger and more secure, I should not need it.

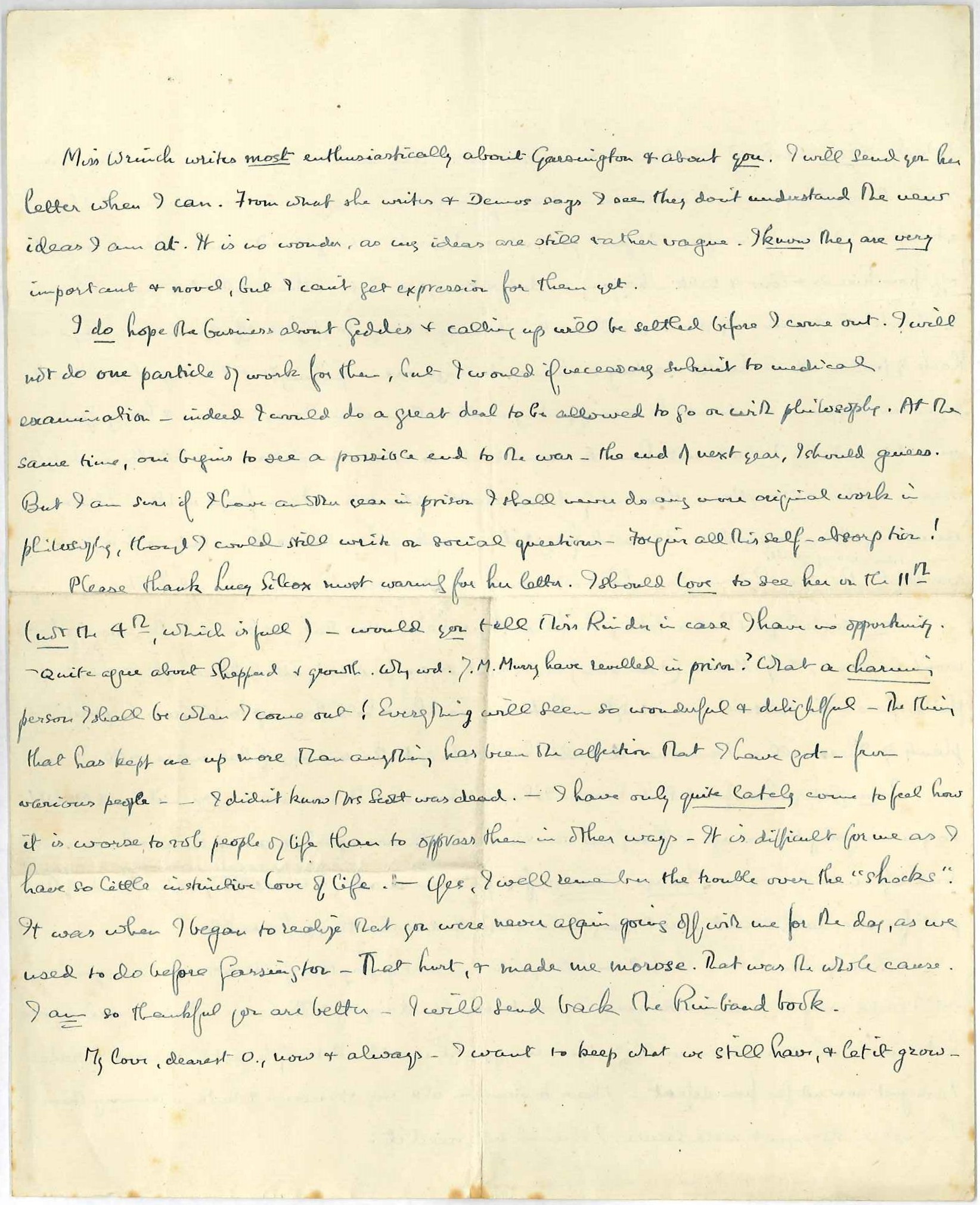

Miss Wrinch writes8 most enthusiastically about Garsington and about you. I will send you her letter when I can. From what she writes and Demos says9 I see they don’t understand the new ideas I am at. It is no wonder, as my ideas are still rather vague. I know they are very important and novel, but I can’t get expression for them yet.

I do hope the business about Geddes and calling up will be settled before I come out. I will not do one particle of work for them, but I would if necessary submit to medical examination10 — indeed I would do a great deal to be allowed to go on with philosophy. At the same time, one begins to see a possible end to the war11 — the end of next year, I should guess. But I am sure if I have another year in prison I shall never do any more original work in philosophy, though I could still write on social questions. Forgive all this self-absorption!

Please thank Lucy Silcox most warmly for her letter.12 I should love to see her on the 11th (not the 4th, which is full) — would you tell Miss Rinder in case I have no opportunity. — Quite agree about Sheppard and growth.13 Why would J.M. Murry have revelled in prison?14 What a charming person I shall be when I come out! Everything will seem so wonderful and delightful. The thing that has kept me up more than anything has been the affection that I have got — from various people. — I didn’t know Mrs Scott15 was dead. — I have only quite lately come to feel how it is worse to rob people of life than to oppress them in other ways. It is difficult for me as I have so little instinctive love of life. — Yes, I well remember the trouble over the “shocks”.16 It was when I began to realize that you were never again going off with me for the day, as we used to do before Garsington. That hurt, and made me morose. That was the whole cause. I am so thankful you are better. I will send back the Rimbaud book.17

My love, dearest O., now and always. I want to keep what we still have, and let it grow.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from a digital scan of the unsigned, thrice-folded, single-sheet original in BR’s hand in the Morrell papers at the University of Texas at Austin. The scan was accompanied by a scan of a sheet “2”, dated “Thurs.” It was determined that this sheet belongs to Letter 102.

- 2

cannot be sure of finding it still there when I come out A hint of jealousy about Colette, resulting from her “wretched scrap” of a letter received that day (see Letter 71).

- 3

worse imprisonment till the end of the war BR was hinting at the possibility of prolonged detention in military or civil custody, should he be called up for military service after his release from Brixton, have his claim for an absolute exemption rejected, and then refuse to undertake “alternative” war work. In April 1918 the upper-age limit for British conscripts had been raised from 40 to 50 (see Letter 6).

- 4

Geo. Birmingham’s have not come Yet Ottoline’s letter to BR of 11 August (BRACERS 114754) indicated that some books by this author had been sent. George A. Birmingham was the pen name of prolific Irish novelist and Anglican cleric, James Owen Hannay (1865–1950).

- 5

nor Miss Wrinch’s philosophical books Possibly the “bound volumes of Psych. Review and Am. J. of Psych., 1912ff”, referred to in Letter 51. If these scholarly journals were, indeed, the “philosophical books” requested from Wrinch, he obviously did receive them, eventually — perhaps courtesy of G.H. Hardy, whom BR had suggested to his brother as an alternate courier. BR’s list of philosophical prison reading (Papers 8: App. III) includes 23 articles from volumes 18–23 (1911–16) of The Psychological Review, and another seven from volumes 21 and 23 (1910 and 1912) of The American Journal of Psychology.

- 6

found Phil. Essays ... all MIND BR’s Philosophical Essays (London: Longmans, Green, 1910), which Ottoline had reported lost (see Letter 61). Ottoline located her copy, which she prized highly, in the “Cottage” at Garsington Manor. Chastising herself for her distress at losing the book, she also wrote: “I remember you and know what you would say — and say to myself ‘It is only matter’”. BR’s jocular correction nevertheless hinted at his latest philosophical preoccupation, as reflected in much of his prison reading.

- 7

going to Swanage … begin all over again BR was recalling an idyllic, and keenly anticipated, three days spent with Ottoline at this Dorset seaside resort in April 1911, just as their affair was beginning (see BRACERS 17099 and 17100).

- 8

Miss Wrinch writes Three letters (BRACERS 81966, 81967 and 81968) from Wrinch in August 1918 are extant, but none is the letter BR sent Ottoline. Nor is that letter among Ottoline’s papers in the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin.

- 9

Demos says While BR was in jail, Demos had started a rather one-sided affair with Wrinch (“it is no fun if the relation is not symmetrical”, she complained to BR). Demos had visited BR in prison earlier the day of the present letter, 14 August.

- 10

but I would … submit to medical examination Some “absolutist” C.O.s even refused to be medically examined to determine fitness or otherwise for military service, and in May 1916 the No-Conscription Fellowship issued a circular advising non-compliance. On 14 July BR told Ottoline that while he did not disapprove of the procedure on grounds of conscience, he was mindful of offending NCF colleagues by this breach of their “etiquette” (Letter 40).

- 11

see a possible end to the war In light of significant strategic gains made by the Allies during his imprisonment (see Letters 30, 44 and 60), BR’s forecasting of the war’s likely duration became slightly more optimistic — although not before his forlorn prediction to Gladys Rinder of its continuation “till Germany is as utterly defeated as France was in 1814, and that that will take about another ten years” (Letter 20). Yet BR clearly underestimated the rapidity with which German military resistance was crumbling on the Western Front. The final Allied victory was achieved extremely quickly after Germany’s previously impregnable Hindenburg Line of defences was breached at the end of September. “Was anything ever so dramatic as the collapse of the ‘enemy’”, he asked Ottoline on 9 November 1918 (BRACERS 18703).

- 12

her letterSilcox’s letter was dated 10 August 1918 (BRACERS 80379). In it she wrote about staying with Ottoline and about Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians, mentioning BR’s “review” (presumably a reference to Letter 7). She also discussed the lack of education in village girls and suggested visiting BR on 4 or 11 September (she did so on the 11th).

- 13

Quite agree about Sheppard and growth John T. Sheppard (1881–1968) was a close friend of J.M. Keynes and, like the economist, a Cambridge Apostle and Fellow of King’s College, which he later served as provost (1933–54). A classical scholar, Sheppard was at this time working as a translator for the War Office. Ottoline had critiqued him thus: “He never seems to grow. He is so awfully nice and good and kind inside with a fountain of thought about old subjects, but he never seems keen or interested in new ones.”

- 14

J.M. Murry … revelled in prison Without explaining, Ottoline had suggested to BR that the critic and editor J. Middleton Murry would likely have “revelled in it <imprisonment> and in exile from everyone” (11 Aug. 1918, BRACERS 114754). Ottoline’s comment seems odd and a shade gratuitous, since Murry was working for the War Office at this time and therefore hardly likely to find himself in BR’s situation. For BR’s outrage at Murry’s scornful treatment of Sassoon’s poetry, see Letters 39and48 especially.

- 15

Mrs Scott “Of Ham. Ottoline’s aunt by a first marriage.” (BR’s note at BRACERS 119468.) Caroline Louisa Warren Scott, née Burnaby (1832–1918), who died 6 July, was successively the widow of Charles Bentinck, Ottoline’s brother, and of Henry Warren Scott; she was a great-grandmother to Elizabeth II.

- 16

I well remember the trouble over the “shocks” Shocks are sheaves of grain arranged to keep the heads off the field. On 11 August 1918 (BRACERS 114754), Ottoline wrote: “The Harvest is being got in and I have been helping to ‘shock’. Do you remember how you hated it and how hurt I was about it — when you stood and watched me!” She immensely enjoyed shocking but not BR: “I tried to get Bertie to come and help; he came one day but it was clear that he was hopelessly bored to death — his face drawn out to its full length — and longed to get away” (Ottoline at Garsington: Memoirs of Lady Ottoline Morrell, 1915–1918, ed. R. Gathorne-Hardy [London: Faber and Faber, 1974], p. 47).

- 17

I will send back the Rimbaud book Probably Paterne Berrichon, Jean-Arthur Rimbaud, le poète (1854–1873) (Paris: Mercure de France, 1912). Next day BR instructed Colette to “Please send Paterne Berrichon on Rimbaud to Ottoline — it is hers and she wants it” (Letter 71).

Textual Notes

- a

I am needing novels. Inserted.

Annotations by BR

In the late 1940s, when BR was going through his archives, and in the 1950s when he was revising his Autobiography, he would occasionally annotate letters. He did this to sixteen of the Brixton letters. Links to them are gathered here for convenient access to these new texts. In the annotations to the letters they are always followed by “(BR’s note.)”

Letter 2, note 5 happy.

5, note 6 congratulations to G.J.

9, note 28 bit of Girondin history.

12, note 6 friend.

15, note 2 (the letter in general).

20, note 7 G.J.

31, note 3 Dr’s treatment.

40, notes 9, 10 Ld. G.L.G, Lady B’s.

44, note 14 S.S.

48, note 48 Mother Julian’s Bird.

57, notes 13, 16 Ld. Granville’s to Ly. B., bless that Dr. … seat of intellect.

70, note 15 Mrs Scott.

73, note 12 E.S.P. Haynes.

76, note 4 Cave.

85, note 2 Marsh on Rupert.

102, notes 23, 28 Woolley, K. Lonsdale.

General Annotations

Brett note from Auto. 2: 93

Cousens note from Auto. 2: 71

Kyle note with her letters to BR

Rinder note from Auto. 2: 88n.

Silcox note on BRACERS 80365

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.

Dorothy Wrinch

Dorothy Maud Wrinch (1894–1976), mathematician, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. She studied mathematics and philosophy at Girton College, Cambridge, and came under BR’s influence in her second year when she took his course on mathematical logic. She taught mathematics at University College, London, 1918–21, and then at Oxford, 1922–30. Her first publications were in mathematical logic and philosophy, and during the 1920s she wrote on the philosophy of science. But in the 1930s her interests turned to mathematical biology and crystallography, and in 1935 she moved to the United States on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship and remained there for the rest of her life. Unfortunately, as a biologist she is best known for a long and stubborn controversy with Linus Pauling about the structure of proteins in which he was right and she was wrong. See Marjorie Senechal, I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science (New York: Oxford U. P., 2013). Chapter 7 is devoted to Wrinch’s interactions with BR in Brixton.

Fellowship Plan

Since the upper-age limit for compulsory military service had been increased to 50 in April 1918, BR was faced with the unnerving prospect of being conscripted after his release from Brixton. Early in his imprisonment he was already wondering about his “position when I emerge from here” (Letter 9). While his conviction was still under appeal, he had broached with Clifford Allen and Gilbert Murray the possibility of avoiding military service, not by asserting his conscientious objection to it, but by obtaining accreditation of his philosophical research as work of national importance (see note to Letter 24). The Pelham Committee, set up by the Board of Trade in March 1916, was responsible for the designation of essential occupations and recommending to the local tribunals, who adjudicated claims for exemption from military service, that C.O.s be considered for such positions. BR reasoned to Murray on 2 April that a dispensation to practise philosophy (as opposed to working outside his profession), would enable to him to “avoid prison without compromise” — i.e., of his political and moral opposition to conscription (BRACERS 52367). Although BR intended to withdraw from political work, he told Murray two days later, he would not promise to abstain from peace campaigning (BRACERS 52369). It should be noted that C.O.s who accepted alternative service in special Home Office camps were expressly prohibited from engaging in pacifist activities (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 231).

BR was far from sanguine about the prospect of success before a local tribunal. But he came to think (by early June) that his chances would be improved if his academic supporters interceded directly with the Minister of National Service, Sir Auckland Geddes. In addition, he calculated that such entreaties would be more effective if those acting on his behalf could secure and even endow a fellowship for him and thereby have “something definite to put before Geddes” (Letter 12; see also Letters 15 and 19). BR definitely wanted to rededicate himself to philosophy and would have welcomed a new source of income from academic employment (see Letter 22). But the “financial aspect was quite secondary”, he reminded Frank on 24 June (Letter 27); he was interested in the fellowship plan primarily as a safeguard against being called up, for teachers over 45 were not subject to the provisions of the recently amended Military Service Act. In the same letter, however, BR told his brother that “I wish it <the plan> dropped” on account of reservations expressed to him in person by Wildon Carr and A.N. Whitehead (see also Letter 31), two philosophers whom he respected but who seemed to doubt whether BR’s financial needs were as great as they appeared (see note to Letter 102).

Yet BR’s retreat was only temporary. On 8 August, he expressed to Ottoline a renewed interest in the initiative, and a few days later, she, her husband and Gladys Rinder met in London to discuss the matter. As Ottoline reported to BR, “we all felt that it was useless to wait for others to start and we decided that P. and I should go and see Gilbert M. and try and get him to work it with the Philosophers” (11 Aug. 1918, BRACERS 114754). BR probably wanted Murray to spearhead this lobbying (see also Letters 65 and 70) because of his political respectability and prior success in persuading professional philosophers to back an appeal to the Home Secretary for BR’s sentence to be served in the first division (see Letter 6). Murray did play a leading role but not until early the following month, when BR was anxious for the fellowship plan to succeed as his release date neared. The scheme finally gathered momentum after a meeting between Ottoline, Rinder and Carr on 6 September 1918, at which the philosopher and educationist T. Percy Nunn, another academic supporter of BR, was also present. Within a few days Murray had drafted a statement with an appeal for funds, which was endorsed by Carr, Whitehead, Nunn, Samuel Alexander, Bernard Bosanquet, G. Dawes Hicks, A.E. Taylor and James Ward. This memorial was then circulated in confidence to philosophers and others, but only after BR’s release from Brixton. (Financial pledges had already been made by a few of BR’s friends and admirers, notably Lucy Silcox and Siegfried Sassoon.) BR’s solicitor, J.J. Withers, became treasurer of this endowment fund, the goal of which was to provide BR with £150 or £200 per annum over three years. On 30 August BR had confessed to Ottoline that he did not want an academic position “very far from London” (Letter 89) and reiterated this desire in a message to Murray communicated by Rinder (Letter 97). On 6 September Rinder (BRACERS 79633) hinted that she already knew where the appointment would be, but there are no other indications that a particular establishment had been decided upon. Ultimately, no affiliation was contemplated for BR, so the memorial stated, because “in the present state of public feeling no ordinary university institution is likely to be willing to employ him as a teacher” (copy in BRACERS 56750). The circular talked instead of a “special Lectureship”, and the £100 BR received from the fund early in 1919 was explicitly issued as payment for lectures (on “The Analysis of Mind”; see syllabus, in Papers 9: App. III.1) that he would deliver that spring. BR’s solicitor also informed him that provision existed to pay him a further £100 for an autumn lecture course (see syllabus, ibid.: App. III.2), and Withers anticipated that these arrangements might “last two or three years” (2 Jan. 1919, BRACERS 81764). BR had already obtained a £50 gift from the fund in November 1918. Somewhat ironically, the critical importance of a teaching component to the fellowship plan — as insurance against conscription — was reduced by the authorities hesitating to hound BR any further after his imprisonment, and all but nullified by the end of the war a few weeks later. (There were no fresh call-ups, but the last of the C.O.s already in prison were not released until August 1919, and conscription remained in effect until April 1920.)

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).

Gilbert Murray

Gilbert Murray (1866–1957), distinguished classical scholar and dedicated liberal internationalist. He was Regius Professor of Greek at Oxford, 1908–36, and chair of the League of Nations Union, 1923–36. He and BR enjoyed a long and close friendship that was ruptured temporarily by bitter disagreement over the First World War. After Murray published The Foreign Policy of Sir Edward Grey, 1906–1915, in defence of Britain’s pre-war diplomacy, BR responded with a detailed critique, The Policy of the Entente, 1904–1914: a Reply to Professor Gilbert Murray (37 in Papers 13). Yet Murray still took the lead in campaigning to get BR’s sentence reassigned from the second to the first division and (later) in leading an appeal for professional and financial backing of an academic appointment for BR upon his release (the “fellowship plan”, which looms large in his prison correspondence). BR was still thankful for Murray’s exertions some 40 years later. See his portrait of Murray, “A Fifty-Six Year Friendship”, in Murray, An Unfinished Autobiography with Contributions by His Friends, ed. Jean Smith and Arnold Toynbee (London: Allen & Unwin, 1960).

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

J. Middleton Murry

J. Middleton Murry (1889–1957), critic and editor, was educated in classics at Brasenose College, Oxford, before establishing in 1911 the short-lived avant-garde journal, Rhythm. In May 1918 he married the author Katherine Mansfield, to whose literary legacy he became devoted after her death from tuberculosis only five years later. The couple were frequent visitors to Garsington Manor, and Murry appears at one time to have had a romantic yearning for Ottoline (see note to Letter 48). Although Murry’s scornful treatment of Sassoon’s poetry annoyed BR (see Letter 39), he became, nevertheless, a frequent contributor to The Athenaeum during Murry’s two-year stint as its editor (1919–21). After the ailing literary weekly merged with The Nation in 1921, Murry continued his vigorous promotion of modernism in the arts from the helm of his own monthly journal, The Adelphi, which he edited for 25 years. During the First World War he worked as a translator for the War Office but became an uncompromising pacifist in the 1930s. One of the last assignments of his journalistic career was as editor of the pacifist weekly, Peace News (1940–46). Source: Oxford DNB.

Lucy Silcox

Lucy Mary Silcox (1862–1947), headmistress of St. Felix school in Southwold, Suffolk (1909–26), feminist, and long-time friend of BR’s, whom he had known since at least 1906. On a letter from her, he wrote that she was “one of my dearest friends until her death ” (BR’s note, BRACERS 80365). After learning of BR’s conviction and sentencing by the Bow St. magistrate, a distraught Silcox reported to him that she had been “shut out in such blackness and desolation” (2 Feb. 1918, BRACERS 80377). During BR’s imprisonment it was Silcox who brought to his attention the Spectator review of Mysticism and Logic. Years later (in 1928), when BR and Dora Russell had launched Beacon Hill School, Silcox came with Ottoline Morrell to visit it.

Lytton Strachey

Lytton Strachey (1880–1932), biographer, reviewer and a quintessential literary figure of the Bloomsbury Group. He is best known for his debunking portraits of Cardinal Manning, Florence Nightingale, Dr. Arnold and General Gordon, published together as Eminent Victorians (London: Chatto & Windus, 1918; Russell’s library), which BR read in Brixton with great amusement as well as some critical reservations (see Letter 7). Although Strachey was homosexual, he and the artist Dora Carrington were devoted to each other and from 1917 lived together in Tidmarsh, Berkshire. BR had become acquainted with the somewhat eccentric Strachey, a fellow Cambridge Apostle, while his slightly younger contemporary was reading history at Trinity College. He admired Strachey’s literary gifts, but doubted his intellectual honesty. Almost three decades later BR fleshed out the unflattering thumbnail of Strachey drawn for Ottoline in Letter 7, in a “Portrait from Memory” for BBC radio. Strachey was “indifferent to historical truth”, BR alleged in that broadcast, “and would always touch up the picture to make the lights and shades more glaring and the folly or wickedness of famous people more obvious” (The Listener 48 [17 July 1952]: 98). Main biography: Michael Holroyd, Lytton Strachey: a Critical Biography, 2 vols. (London: Heinemann, 1967–68).

Raphael Demos

Raphael Demos (1892–1968), one of BR’s logic students in the autumn of 1916. Then on a Sheldon travelling fellowship, Demos eventually returned to Harvard where he taught philosophy for the rest of his career. Russell had taught him at Harvard in 1914 and described him in his Autobiography (1: 212). In 1916–17 BR recommended two of his articles to G.F. Stout, the editor of Mind (“A Discussion of a Certain Type of Negative Proposition”, Mind 26 [Jan. 1917]: 188–96; and “A Discussion of Modal Propositions and Propositions of Practice”, 27 [Jan. 1918]: 77–85); see BRACERS 54831 and 2962 (and for Demos’s letters to BR in 1917 about the submissions, BRACERS 76495 and 76496, and BR’s reply to the first, BRACERS 838).

Siegfried Sassoon

Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967), soldier awarded the MC and anti-war poet. Ottoline had befriended him in 1916, and the following year, when Sassoon refused to return to his regiment after being wounded, she and BR helped publicize this protest, which probably saved him from a court martial. BR even assisted Sassoon in revising his famous anti-war statement, which was read to the House of Commons by a Liberal M.P. on 30 July 1917. Sassoon’s actions were an embarrassment to the authorities, for he was well known as both a poet and a war hero. Unable to hush the case up, the government acted with unexpected subtlety and declared Sassoon to be suffering from shell-shock and sent him to Craiglockhart War Hospital for Officers, near Edinburgh. After a period of recuperation in Scotland overseen by military psychiatrist Capt. W.H.R. Rivers, Sassoon decided to return to the Front (see Jean Moorcroft Wilson, Siegfried Sassoon: Soldier, Poet, Lover, Friend [New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2014]). He was again wounded in July 1918 and was convalescing in Britain during some of BR’s imprisonment. Although each admired the other’s stand on the war, BR and Sassoon were never close in later years. Yet Sassoon did pledge £50 to the fellowship plan fund (see BRACERS 114758), and decades later he donated a manuscript in support of BR’s International War Crimes Tribunal (see BRACERS 79066).

Sir Auckland Geddes

Sir Auckland Geddes (1879–1954; 1st Baron Geddes, 1942) was returned unopposed as Conservative M.P. for Basingstoke in a by-election held in October 1917. Before this entry into civilian public life, he held the rank of Brigadier-General as director of recruiting at the War Office. He was an ardent champion of conscription even in peacetime and had a long-standing interest in the military, which he expressed before the war as a volunteer medical officer in the British Army Reserve. He had studied medicine and was Professor of Anatomy at McGill University, Montreal, when the outbreak of war prompted an immediate return to Britain in order to enlist. After a riding accident rendered Geddes unfit for front-line duties, he became a staff officer in France with a remit covering the supply and deployment of troops. He performed similar duties at the War Office until his appointment in August 1917 as a Minister of National Service with broad powers over both military recruitment and civilian labour. Geddes held two more Cabinet positions in Lloyd George’s post-war Coalition Government before his appointment in 1920 as British Ambassador to the United States. After returning from Washington on health grounds three years later, Geddes embarked upon a successful business career, becoming chairman in 1925 of the Rio Tinto mining company. See Oxford DNB.

The Nation

A political and literary weekly, 1907–21, edited for its entirety by H.W. Massingham before it merged with The Athenaeum and then The New Statesman. BR regularly contributed book reviews, starting in 1907. During his time at Brixton, he published there a book review (14 in Papers 8; mentioned in Letters 4 and 102) and a letter to the editor (Letter 39). In August 1914 The Nation hastily abandoned its longstanding support for British neutrality, rejecting an impassioned defence of this position written by BR on the day that Britain declared war (1 in Papers 13). For the next two years the publication gave its editorial backing (albeit with mounting reservations) to the quest for a decisive Allied victory. At the same time, it consistently upheld civil liberties against the encroachments of the wartime state, and by early 1917 had started calling for a negotiated peace as well. The Nation had recovered its dissenting credentials, but for allegedly “defeatist” coverage of the war was hit with an export embargo imposed in March 1917 by Defence of the Realm Regulation 24B.

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.