Brixton Letter 62

BR to Constance Malleson

August 8, 1918

- ALS

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-62SLBR 2: #319

BRACERS 19341

<Brixton Prison>1

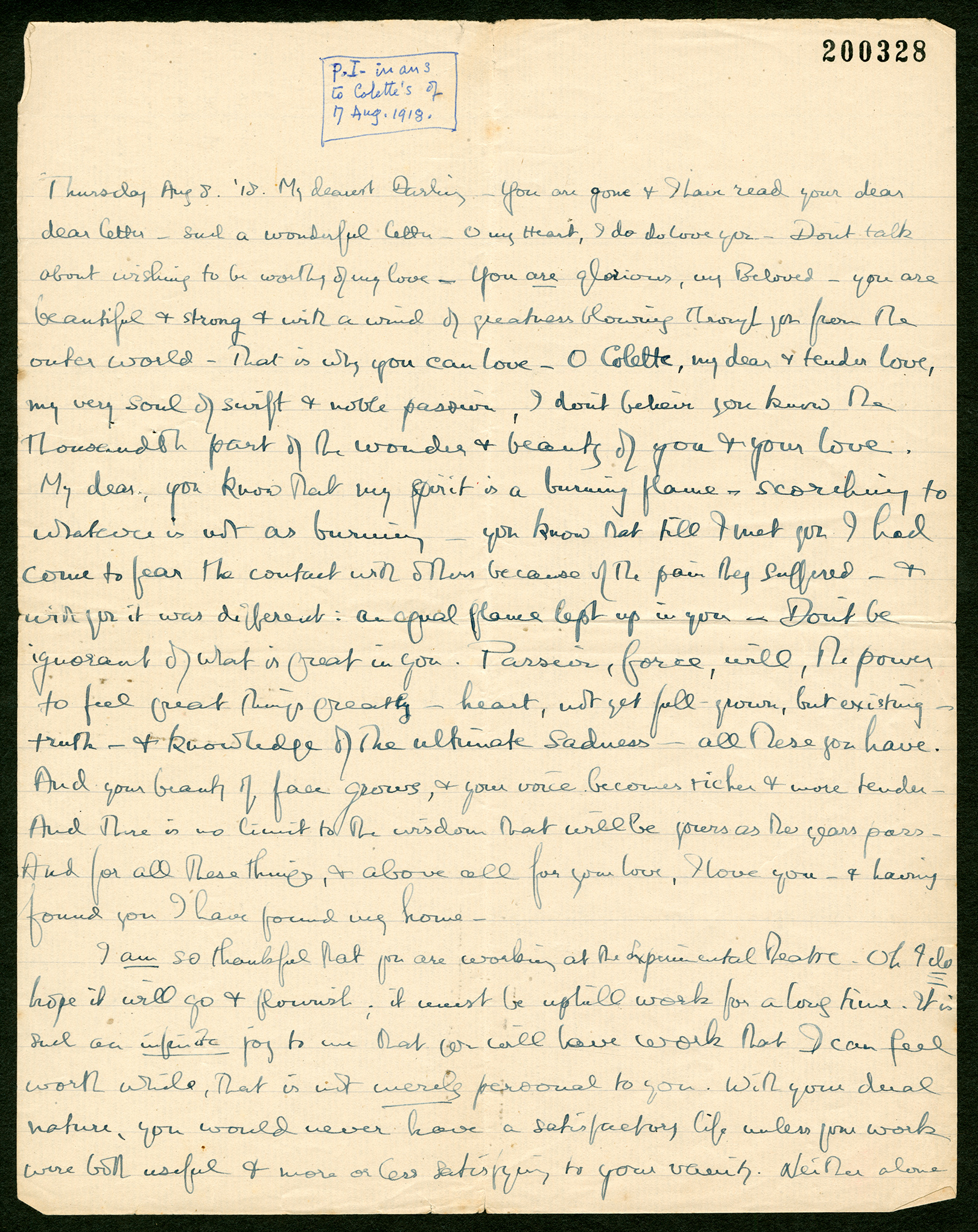

Thursday

Aug. 8. ’18.

My dearest Darling

You are gone and I have read your dear dear letter2 — such a wonderful letter. O my Heart, I do do love you. Don’t talk about wishing to be worthy of my love. You are glorious, my Beloved — you are beautiful and strong and with a wind of greatness blowing through you from the outer world. That is why you can love. O Colette, my dear and tender love, my very soul of swift and noble passion, I don’t believe you know the thousandth part of the wonder and beauty of you and your love. My dear, you know that my spirit is a burning flame — scorching to whatever is not as burning — you know that till I met you I had come to fear the contact with others because of the pain they suffered — and with you it was different: an equal flame leapt up in you. Don’t be ignorant of what is great in you. Passion, force, will, the power to feel great things greatly — heart, not yet full-grown, but existing — truth — and knowledge of the ultimate sadness — all these you have. And your beauty of face grows, and your voice becomes richer and more tender. And there is no limit to the wisdom that will be yours as the years pass. And for all these things, and above all for your love, I love you — and having found you I have found my home.

I am so thankful that you are working at the Experimental Theatre. Oh I doa hope it will go and flourish; it must be uphill work for a long time. It is such an infinite joy to me that you will have work that I can feel worth while,3 that is not merely personal to you. With your dual nature, you would never have a satisfactory life unless your work were both useful and more or less satisfying to your vanity. Neither alone would do. The plan of spending half your work on the ordinary theatre and half addressing envelopes for Miss Rinder was not satisfactory: it was like hopping on one leg for an hour, and then hopping on the other for the next hour, instead of walking on both;b you needed something that combined both impulses, and now you will have it.4

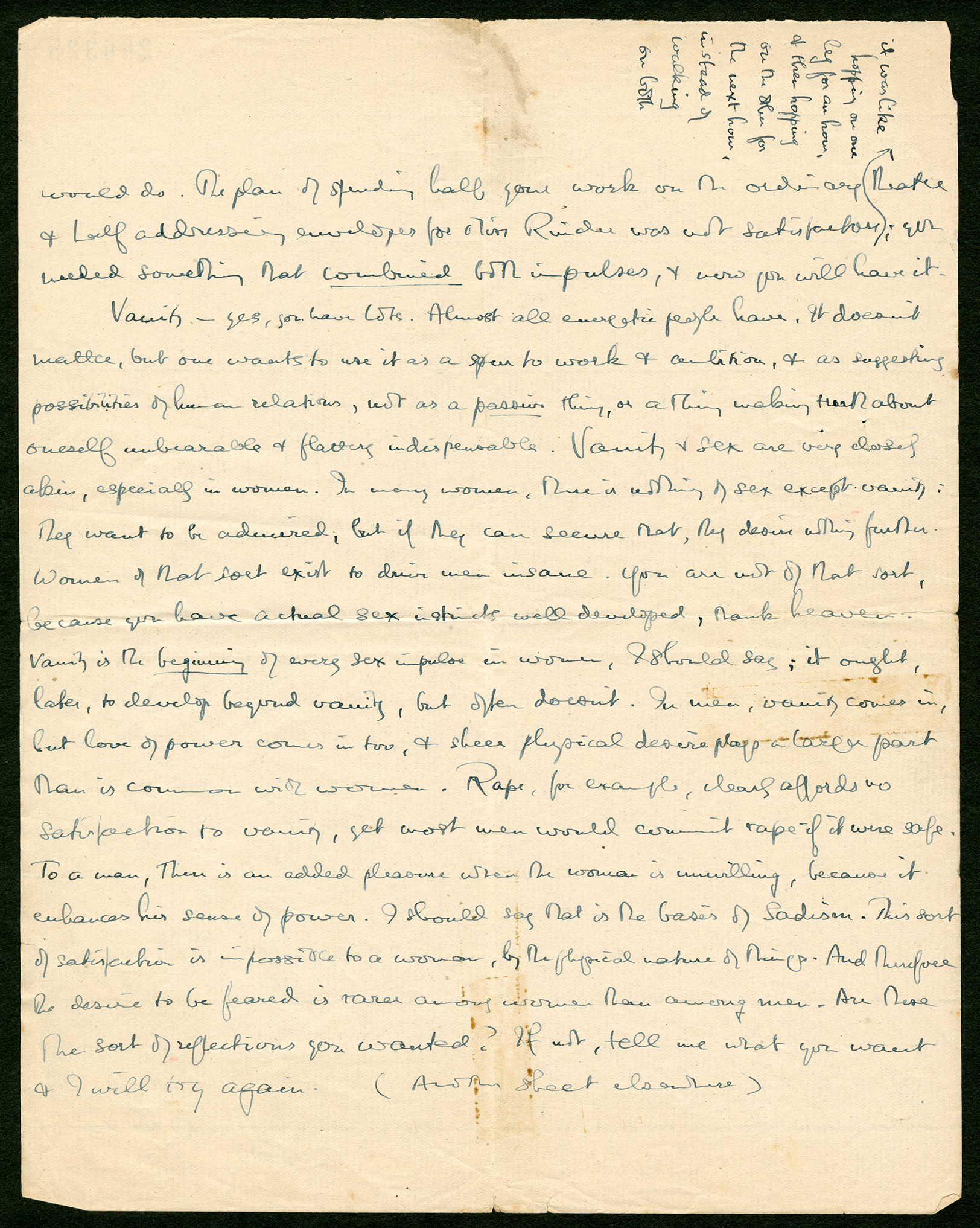

Vanity — yes, you have lots. Almost all energetic people have. It doesn’t matter, but one wants to use it as a spur to work and ambition, and as suggesting possibilities of human relations, not as a passive thing, or a thing making truth about oneself unbearable and flattery indispensable.5 Vanity and sex are very closely akin, especially in women. In many women, there is nothing of sex except vanity: they want to be admired, but if they can secure that, they desire nothing further. Women of that sort exist to drive men insane. You are not of that sort, because you have actual sex instincts well developed, thank heaven. Vanity is the beginning of every sex impulse in women, I should say; it ought, later, to develop beyond vanity, but often doesn’t. In men, vanity comes in, but love of power comes in too, and sheer physical desire plays a larger part than is common with women. Rape, for example, clearly affords no satisfaction to vanity, yet most men would commit rape if it were safe.6 To a man, there is an added pleasure when the woman is unwilling, because it enhances his sense of power. I should say that is the basis of Sadism. This sort of satisfaction is impossible to a woman, by the physical nature of things. And therefore the desire to be feared is rarer among women than among men. Are these the sort of reflections you wanted?7 If not, tell me what you want and I will try again. (Another sheet elsewhere)

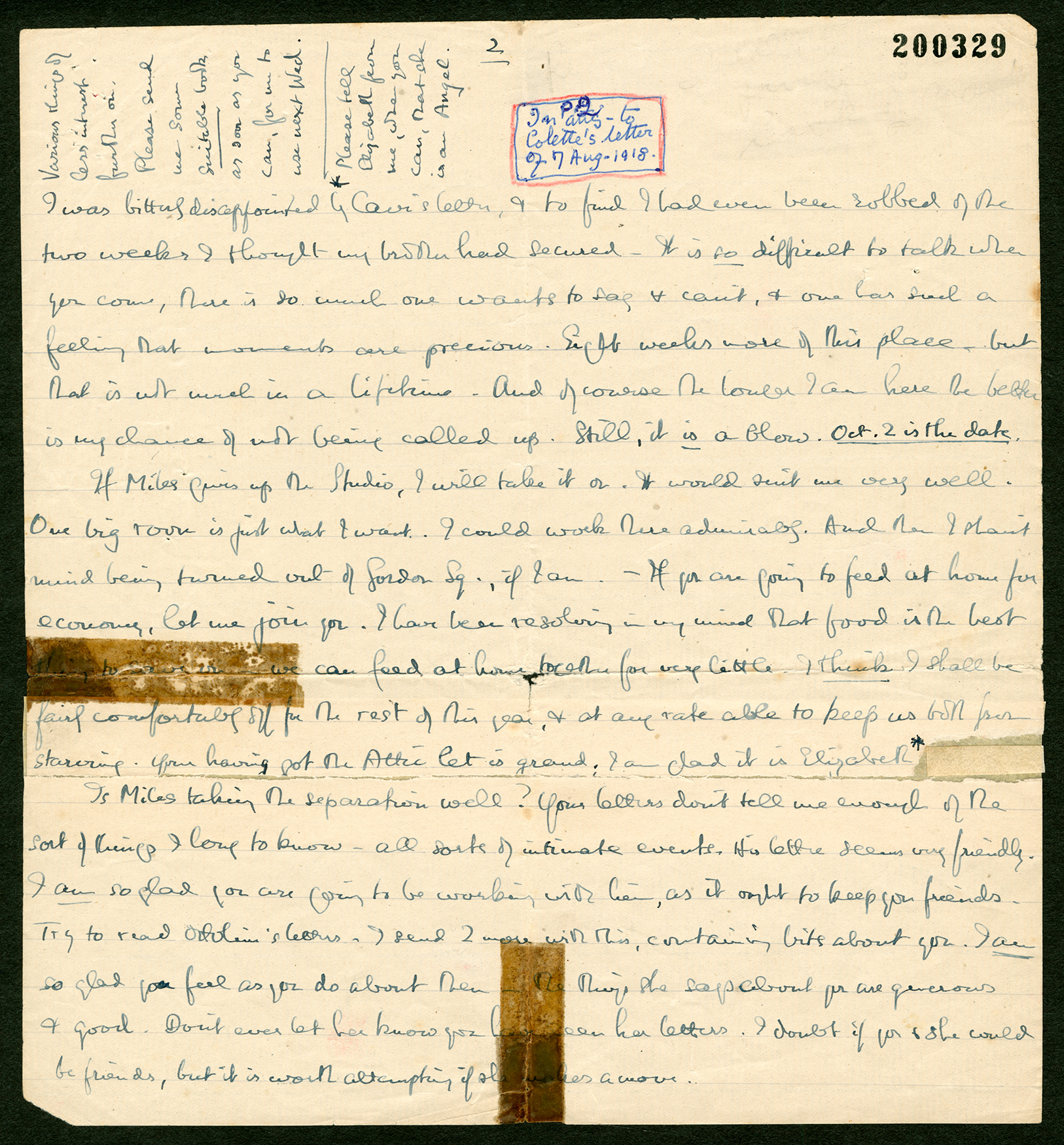

I was bitterly disappointed by Cave’s letter,8 and to find I had even been robbed of the two weeks I thought my brother had secured. It is so difficult to talk when you come, there is so much one wants to say and can’t, and one has such a feeling that moments are precious. Eight weeks more of this place — but that is not much in a lifetime. And of course the longer I am here the better is my chance of not being called up.9 Still, it is a blow. Oct. 2 is the date.10

If Miles gives up the Studio,11 I will take it on. It would suit me very well. One big room is just what I want. I could work there admirably. And then I shan’t mind being turned out of Gordon Sq., if I am. — If you are going to feed at home for economy, let me join you. I have been resolving in my mind that food is the best thing to save on — we can feed at home together for very little. I think I shall be fairly comfortably off for the rest of this year, and at any rate able to keep us both from starving. Your having got the Attic let12 is grand; I am glad it is Elizabeth.* <sheet cut and shortened>

————————

* Please tell Elizabeth from me, when you can, that she is an Angel.

————————

Is Miles taking the separation13 well? Your letters don’t tell me enough of the sort of things I long to know — all sorts of intimate events. His letter seems very friendly. I am so glad you are going to be working with him, as it ought to keep you friends. Try to read Ottoline’s letters.14 I send 2 more with this, containing bits about you. I am so glad you feel as you do about them — the things she says about you are generous and good. Don’t ever let her know you have seen her letters. I doubt if you and she could be friends, but it is worth attempting if she makes a move.

I never knew Lafcadio Hearn15 — he is very interesting in his writing. I wonder what Priscilla’s brother16 turned out to be like. — It’s interesting your doing Wuthering Heights.17 You should read Mrs Gaskell’s Life of the Brontés.18 I do hope you will be able to sell it. — My Heart, your last sheet has touched me so — your wanting to lie in my arms and cry19 — it is what I want to do — it fills my eyes with tears to read what you have written. My Colette, I have found with you the love I sought. I might so well have died without finding it — and now I know the dream I had in my heart was not vain imagining, but a creative dream — and with you it has taken substance, no longer haunting, maddeningly, in the night, but walking beside me in the morning sun. I bless you, Beloved, every moment. Goodbye, my lovely one, my Soul, my lamp in this dark world.

B.

Various things of less interest further on. Please send me some suitable book20, c as soon as you can, for me to use next Wed.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from an initialled pair of sheets in BR’s hand in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. Sheet 2 was cut in two, and the top and bottom pieces taped together to make a shortened sheet that may originally have had four more lines of text. The sheets were folded twice. It is unknown what was excised. The letter was published as #319 in Vol. 2 of BR’s Selected Letters.

- 2

your dear dear letter Possibly her letter of 3 August 1918 (BRACERS 113147), although Colette noted that BR did not respond to her letter of 3 August until 13 August (“Letters to Bertrand Russell from Constance Malleson, 1916–1969”, p. 267; typescript in RA).

- 3

work that I can feel worth while It was BR’s opinion, according to Colette, that most “acting was a worthless sort of occupation. He thought it brought out the worst in one’s character: personal ambition, love of admiration” (After Ten Years [London: Cape, 1931], p. 122).

- 4

The plan of spending ... combined both impulses ... you will have it. When Colette began working at the No-Conscription Fellowship she spent her days there and her evenings at the Haymarket acting. Her NCF work included more than addressing envelopes. She found that “the change of work gave me all the rest I wanted” (After Ten Years [London: Cape, 1931], p. 101). Her theatre role ended on 12 August 1916, and she did not act again until she joined a touring company in May 1918. Although she may have had a plan to act in commercial theatre and continue to work at the NCF, such a plan never came to fruition. The “something that combined both impulses” must have involved combining NCF work with the Experimental Theatre that she, Miles Malleson, and others were founding.

- 5

Vanity … indispensable “Do not attempt to live without vanity, since this is impossible, but choose the right audience from which to seek admiration.” BR offered this rather positive view of vanity as one of “My Ten Commandments”, Everyman, 3, no. 62 (3 April 1930): 291, 296.

- 6

most men would commit rape if it were safe How BR reached this conclusion is unknown. In 1942 he wrote: “Rape, of course, must be forbidden, like other personal violence” (“Marriage and the Family” [1942], RA 220.017400–F2). Years later his view of rape and the law was still much ahead of the times. In a 1954 talk on obscenity and illegal sex acts, he outlined his point on rape thus: “Acts prohibiting violence justified. Rape should be illegal because it is assault, not because it is sexual” (Papers 28: 458).

- 7

Vanity … the sort of reflections you wanted? On 25 September 1917 BR wrote an assessment of Colette’s character which he titled “What She Is and What She Might Become” (BRACERS 120470). His assessment was extremely critical — he found that “her vanity is the worst side of her character”. It is hard to imagine how their relationship survived this scathing character study, but it did. Odder still was her request for enlargement of the subject. In her letter of 3 August (BRACERS 113147), Colette had said, “I’d like the subject <of energy and vanity> enlarged upon sometime when you’ve nowt better to do.”

- 8

disappointed by Cave’s letter Although the Home Secretary made some encouraging verbal signals about BR’s release when he met Frank on 26 July, his letter of 5 August 1918 (BRACERS 57178) turned down Frank’s request of 29 July (BRACERS 57181) for an early August release date. But Sir George Cave did indicate that BR, because of his “good conduct and industry”, would be eligible for release at the end of five months, one month short of his six-month sentence.

- 9

being called up BR had been concerned that since the military service age had been raised to 50, he would be called up. Even though he would register as a conscientious objector, he might be kept in prison once he had served his sentence or sent back almost immediately on his release. His fears now appeared to be lessening.

- 10

Oct. 2 is the date. The expected date of BR’s early release from Brixton. In fact he was let out earlier, on 14 September.

- 11

If Miles gives up the StudioMiles had only just moved to the Studio, beginning his separation from Colette which would end in divorce in 1923. The Studio at 5 Fitzroy Street, just off Howland Street, London W1, was originally rented by BR and Colette in November 1917 as a place where they could be together. The Studio provided minimal and noisy accommodation, possibly a reason for Miles wanting to move on after so short a stay. In September he went to Glastonbury for several weeks to produce a play. BR lived at the Studio for a brief time after his release from Brixton.

- 12

got the Attic let Although BR’s sister-in-law, Elizabeth, had rented the Attic (the flat shared by Miles and Colette), she did not live there. Instead she allowed Dorothy Wrinch to do so.

- 13

the separationMiles and Colette had separated; BR had been pushing for such a development.

- 14

Try to read Ottoline’s letters. BR sent out incoming prison letters so they would not accumulate in his cell. Ottoline’s handwriting, though elegant, is very difficult to read.

- 15

Lafcadio Hearn Hearn (1850–1904), an American journalist who was sent to Japan by Harper’s, stayed there, and became a citizen. He wrote several books explaining Japan to the West. Colette had been reading him and asked (BRACERS 113147) if BR had known him.

- 16

Priscilla’s brotherColette described her uncle as Priscilla’s black sheep brother from Australia who had spent his life wandering the world, always doing the wrong thing. She expected to like him, but we never hear how the visit went. His surname was Moore (BRACERS 113147).

- 17

your doing Wuthering HeightsColette had decided to write a dramatization of the novel. She worked on it for some time, but nothing came of the project.

- 18

Life of the Brontés I.e., The Life of Charlotte Brontë (1857), by English author Elizabeth Gaskell (1810–1865), who was celebrated less as a biographer than as a fictional chronicler of Victorian society in such novels as North and South (1854–55).

- 19

your last sheet has touched me so … lie in my arms and cryColette expressed the sentiments that touched BR in her letter of 3 August 1918 (BRACERS 113147).

- 20

suitable book A book suitable for smuggling letters, i.e., one with uncut pages.

Textual Notes

57 Gordon Square

The London home of BR’s brother, Frank, 57 Gordon Square is in Bloomsbury. BR lived there, when he was in London, from August 1916 to April 1918, with the exception of January and part of February 1917.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Dorothy Wrinch

Dorothy Maud Wrinch (1894–1976), mathematician, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. She studied mathematics and philosophy at Girton College, Cambridge, and came under BR’s influence in her second year when she took his course on mathematical logic. She taught mathematics at University College, London, 1918–21, and then at Oxford, 1922–30. Her first publications were in mathematical logic and philosophy, and during the 1920s she wrote on the philosophy of science. But in the 1930s her interests turned to mathematical biology and crystallography, and in 1935 she moved to the United States on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship and remained there for the rest of her life. Unfortunately, as a biologist she is best known for a long and stubborn controversy with Linus Pauling about the structure of proteins in which he was right and she was wrong. See Marjorie Senechal, I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science (New York: Oxford U. P., 2013). Chapter 7 is devoted to Wrinch’s interactions with BR in Brixton.

Elizabeth Russell

Elizabeth Russell, born Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941), was a novelist who in 1891 married Graf von Arnim-Schlagenthin. She became known as “Elizabeth”, the name she used in publishing Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898), and she remained widely known as Elizabeth von Arnim, although the Library of Congress catalogues her as Mary Annette (Beauchamp), Countess von Arnim. She was a widow when she married BR’s brother, Frank, on 11 February 1916. The marriage was quickly in difficulty; she left it for good in March 1919, but they were never divorced and she remained Countess Russell (becoming Dowager Countess after Frank’s death in 1931).

Experimental Theatre

Colette first mentioned that she and Miles were trying to start an Experimental Theatre in a letter of 24 June 1918 (BRACERS 113135), indicating that Miles would earn a tiny income from it. About a month later, she wrote that Elizabeth Russell had subscribed generously to the Theatre and that £700 had been raised, but hundreds still had to be found (BRACERS 113146). A few days later she wrote that Captain Stephen Gordon, a north-country lawyer working for the government, was to be the honorary treasurer, noting that he had “put most of the drive into the whole thing” (BRACERS 113147). During August Colette was happy with her involvement with the Theatre (Letter 68). John Galsworthy came to tea to discuss the project (c.14 Aug., BRACERS 113149). On 2 September she listed the members of the Theatre committee as “Desmond <MacCarthy>, Massingham, Galsworthy, and Dennis (Bradley)” (BRACERS 113155). The following day she wrote that she was learning three parts (BRACERS 113156). In her memoirs, Colette wrote about the “Experimental Little Theatre” but dated it 1919 (After Ten Years [London: Cape, 1931], pp. 129–30). An “artistic” theatre did get founded in 1920 in Hampstead, and John Galsworthy was connected to that venture, The Everyman Theatre — he was part of a reading committee which chose the works to be performed (The Times, 9 Sept. 1919, p. 8). The Everyman Theatre was under the direction of Norman MacDermott. In his book Everymania (London: Society for Theatre Research, 1975), he noted that he met Miles in the summer of 1918: they rented a store in Bloomsbury, had a cabinetmaker build sets, and put on plays with actors “bored with West-End theatres” (p. 10). It is likely that the Everyman Theatre was an out-growth of the Experimental Theatre.

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Home Secretary / Sir George Cave

Sir George Cave (1856–1928; Viscount Cave, 1918), Conservative politician and lawyer, was promoted to Home Secretary (from the Solicitor-General’s office) on the formation of the Lloyd George Coalition in December 1916. His political and legal career peaked in the 1920s as Lord Chancellor in the Conservative administrations led by Andrew Bonar Law and Stanley Baldwin. At the Home Office Cave proved to be something of a scourge of anti-war dissent, being the chief promoter, for example, of the highly contentious Defence of the Realm Regulation 27C (see Letter 51).

Miles Malleson

Miles Malleson (1888–1969), actor and playwright, was born in Croydon, Surrey, the son of Edmund and Myrrha Malleson. He married his first wife, a fellow actor, Lady Constance Annesley (stage name, Colette O’Niel), in 1915. They had met at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts). Their marriage was an “open” one. In 1914 Miles enlisted in the City of London Fusiliers and was sent to Malta. He became ill and was discharged, unfit for further service. He became active in the No-Conscription Fellowship and wrote anti-war stage plays as well as a pamphlet, Cranks and Commonsense (1916). In the 1930s he began to write for the screen and act in films, in which he became a very well-known character actor, as well as continuing his stage career at the Old Vic in London. He married three times: his second marriage was to Joan Billson, a physician (married 1923, divorced 1940), with whom he had two children; his third wife was Tatiana Lieven, an actress (married 1946). He died in London in March 1969.

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

Priscilla, Lady Annesley

Priscilla, Lady Annesley (1870–1941), second wife of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl of Annesley (1831–1908) and mother of Lady Constance Malleson. Colette described her mother as “among the most beautiful women of her day” with a love of bright colours and walking (After Ten Years [London: Cape, 1931], pp. 12–14).

The Attic

The Attic was the nickname of the flat at 6 Mecklenburgh Square, London WC1, rented by Colette and her husband, Miles Malleson. The house which contained this flat is no longer standing. “The spacious and elegant facades of Mecklenburgh Square began to be demolished in 1950. The houses on the north side were banged into dust in 1958. The New Attic was entirely demolished” (“Letters to Bertrand Russell from Constance Malleson, 1916–1969”, p. 109; typescript in RA).

The Studio

The accommodation BR and Colette rented on the ground floor at 5 Fitzroy Street, just off Howland Street, London W1. “It had a top light, a gas fire and ring. A water tap and lavatory in the outside passage were shared with a cobbler whose workshop adjoined” (Colette’s annotation at BRACERS 113087). It was ready to occupy in November 1917.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.