Brixton Letter 57

BR to Ottoline Morrell

August 1, 1918

- ALS

- Texas

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-57

SLBR 2: #318

BRACERS 18683

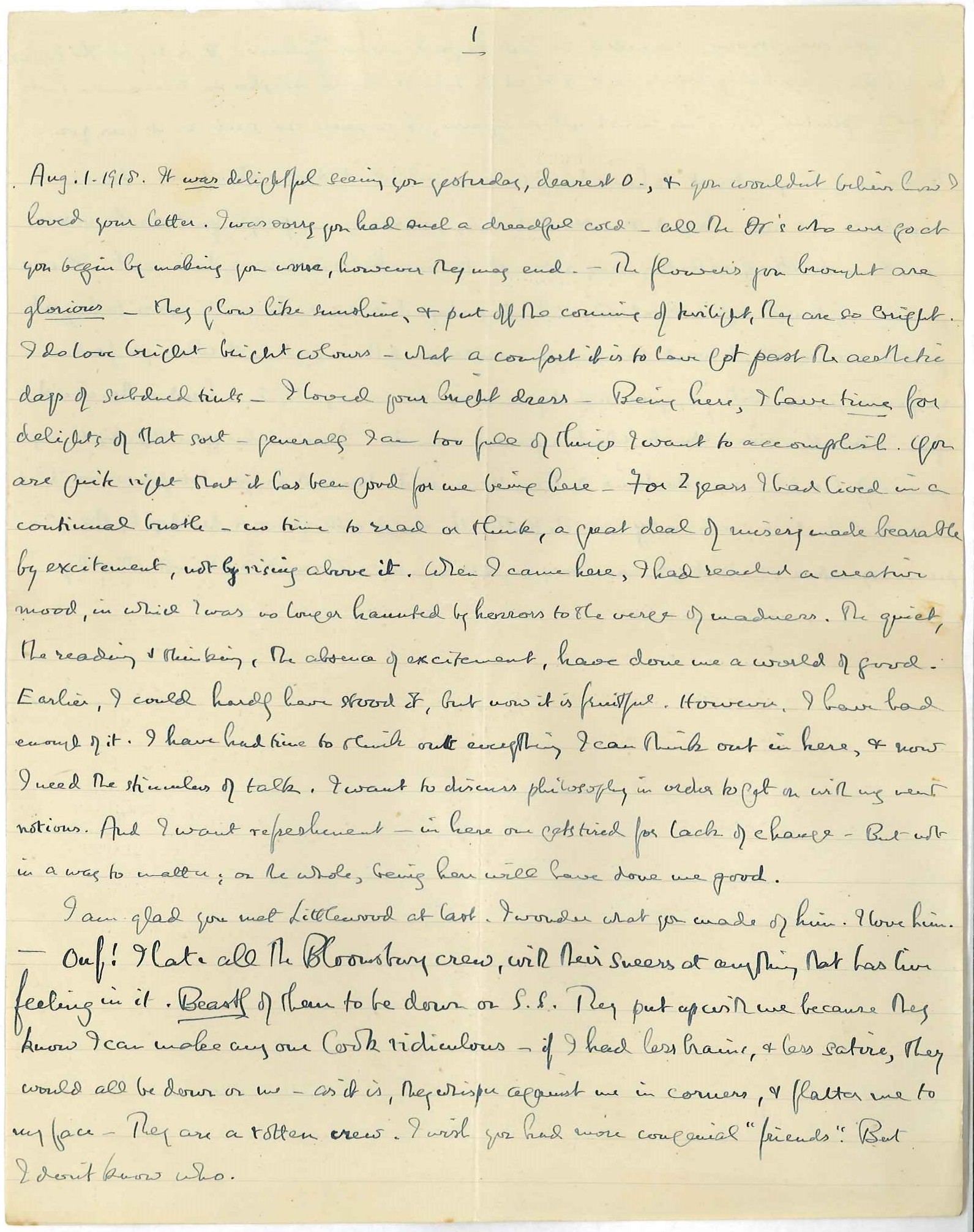

<Brixton Prison>1

Aug. 1. 1918.

It was delightful seeing you yesterday, dearest O., and you wouldn’t believe how I loved your letter.2 I was sorry you had such a dreadful cold — all the Dr’s who ever go at you begin by making you worse, however they may end. — The flowers you brought are glorious — they glow like sunshine, and put off the coming of twilight, they are so bright. I do love bright bright colours — what a comfort it is to have got past the aesthetic days of subdued tints — I loved your bright dress. Being here, I have time for delights of that sort — generally I am too full of things I want to accomplish. You are quite right that it has been good for me being here. For 2 years I had lived in a continual bustle — no time to read or think, a great deal of misery made bearable by excitement, not by rising above it. When I came here, I had reached a creative mood, in which I was no longer haunted by horrors to the verge of madness. The quiet, the reading and thinking, the absence of excitement, have done me a world of good. Earlier, I could hardly have stood it, but now it is fruitful. However, I have had enough of it. I have had time to think out everything I can think out in here, and now I need the stimulus of talk. I want to discuss philosophy in order to get on with my new notions. And I want refreshment — in here one gets tired for lack of change. But not in a way to matter; on the whole, being here will have done me good.

I am glad you met Littlewood at last. I wonder what you made of him. I love him. — Ouf! I hate all the Bloomsbury crew, with their sneers at anything that has live feeling in it. Beastly of them to be down on S.S.3 They put up with me because they know I can make any one look ridiculous — if I had less brains, and less satire, they would all be down on me — as it is, they whisper against me in corners, and flatter me to my face. They are a rotten crew. I wish you had more congenial “friends”. But I don’t know who.

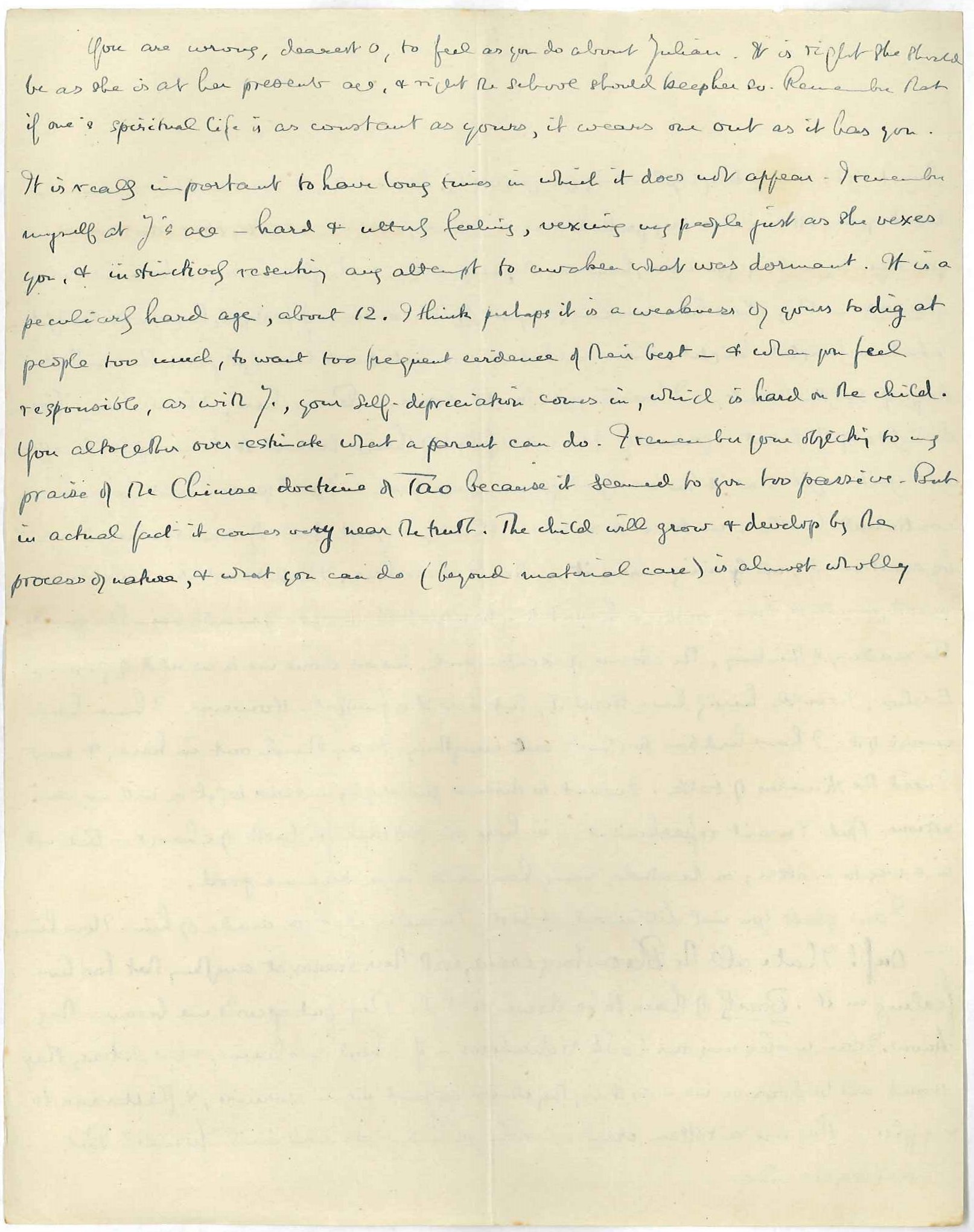

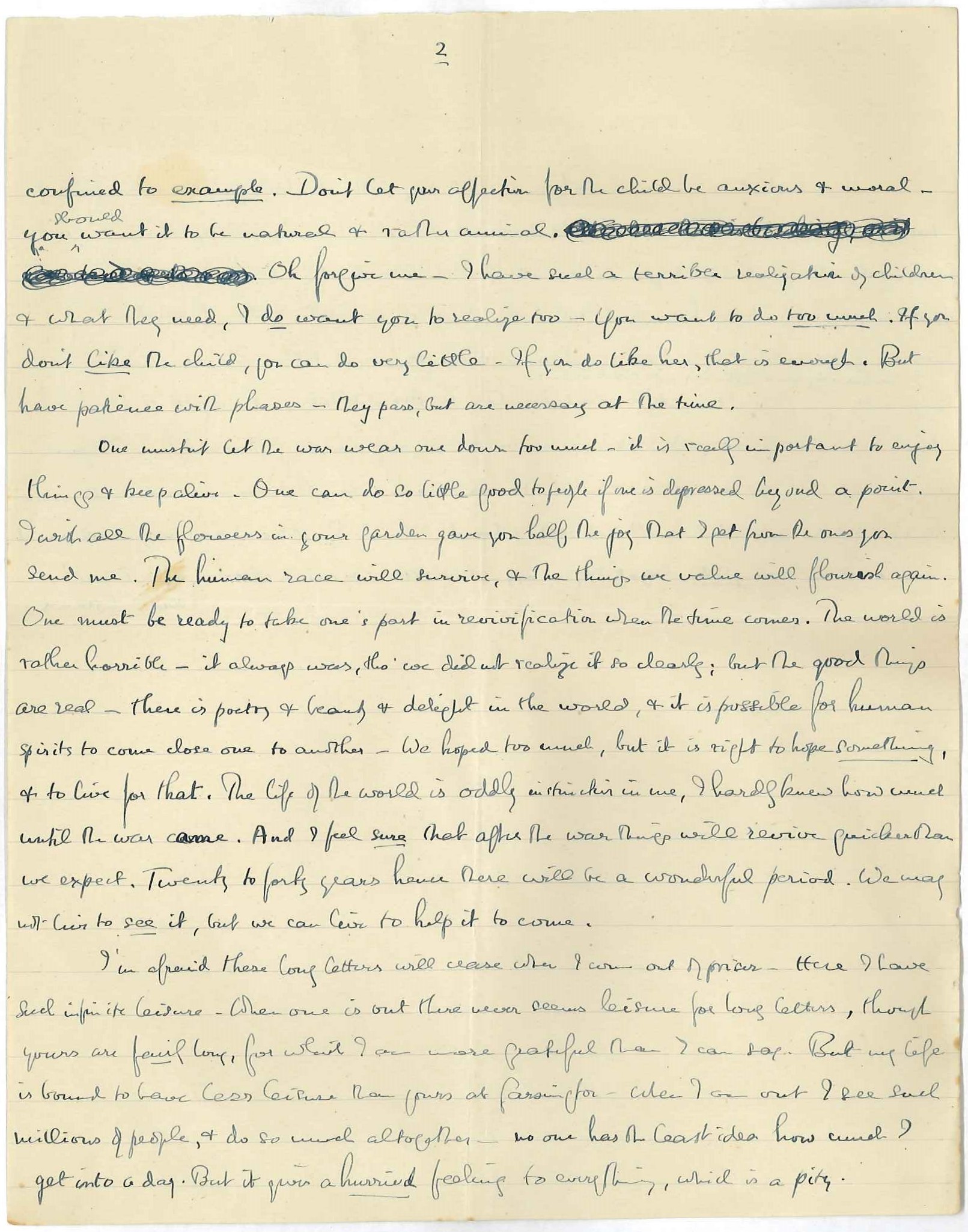

You are wrong, dearest O, to feel as you do about Julian.4 It is right she should be as she is at her present age, and right the school should keep her so. Remember that if one’s spiritual life is as constant as yours, it wears one out as it has you. It is really important to have long times in which it does not appear. I remember myself at J’s age — hard and utterly <un>feeling,5 vexing my people just as she vexes you, and instinctively resenting any attempt to awaken what was dormant. It is a peculiarly hard age, about 12. I think perhaps it is a weakness of yours to dig at people too much, to want too frequent evidence of their best — and when you feel responsible, as with J., your self-depreciation comes in, which is hard on the child. You altogether over-estimate what a parent can do. I remember your objecting to my praise of the Chinese doctrine of Tao6 because it seemed to you too passive. But in actual fact it comes very near the truth. The child will grow and develop by the process of nature, and what you can do (beyond material care) is almost wholly confined to example. Don’t let your affection for the child be anxious and moral — you should want it to be natural and rather animal.a Oh forgive me — I have such a terrible realization of children and what they need, I do want you to realize too. You want to do too much. If you don’t like the child, you can do very little. If you do like her, that is enough. But have patience with phases — they pass, but are necessary at the time.

One mustn’t let the war wear one down too much — it is really important to enjoy things and keep alive. One can do so little good to people if one is depressed beyond a point. I wish all the flowers in your garden gave you half the joy that I get from the ones you send me. The human race will survive, and the things we value will flourish again. One must be ready to take one’s part in revivification when the time comes. The world is rather horrible — it always was, tho’ we did not realize it so clearly; but the good things are real — there is poetry and beauty and delight in the world, and it is possible for human spirits to come close one to another. We hoped too much, but it is right to hope something, and to live for that. The life of the world is oddly instinctive in me, I hardly knew how much until the war came. And I feel sure that after the war things will revive quicker than we expect. Twenty to forty years hence there will be a wonderful period. We may not live to see it, but we can live to help it to come.

I’m afraid these long letters will cease when I come out of prison. Here I have such infinite leisure. When one is out there never seems leisure for long letters, though yours are fairly long, for which I am more grateful than I can say. But my life is bound to have less leisure than yours at Garsington. When I am out I see such millions of people, and do so much altogether — no one has the least idea how much I get into a day. But it gives a hurried feeling to everything, which is a pity.

I am so glad you have made friends with Elizabeth — she loves you. I am very fond of her, but embarrassed by the necessity of not rousing my brother’s jealousy, which is quite oriental. I wonder what you will make of Miss Wrinch.7 She seems to have blossomed out since I have been here, but I should think it would be rather theoretical. I wonder if you will find her so academic that you can’t take any interest in her. I hope not. I like her very much — she has very good brains.b — I am delighted about Ka Cox and Arnold Foster8 — she is just right for him. And he will afford full scope for her maternal impulses. — I wonder how P’s speech9 went off — I hope it was a success. I hear America says the war is to end in January 1920. I dare say that is about right, though I think Sp. 1920 more likely. I believe it will end in complete defeat of Germany — like 1814.10We are in 1810 now, after Tilsit.11 (sheet 3 follows)

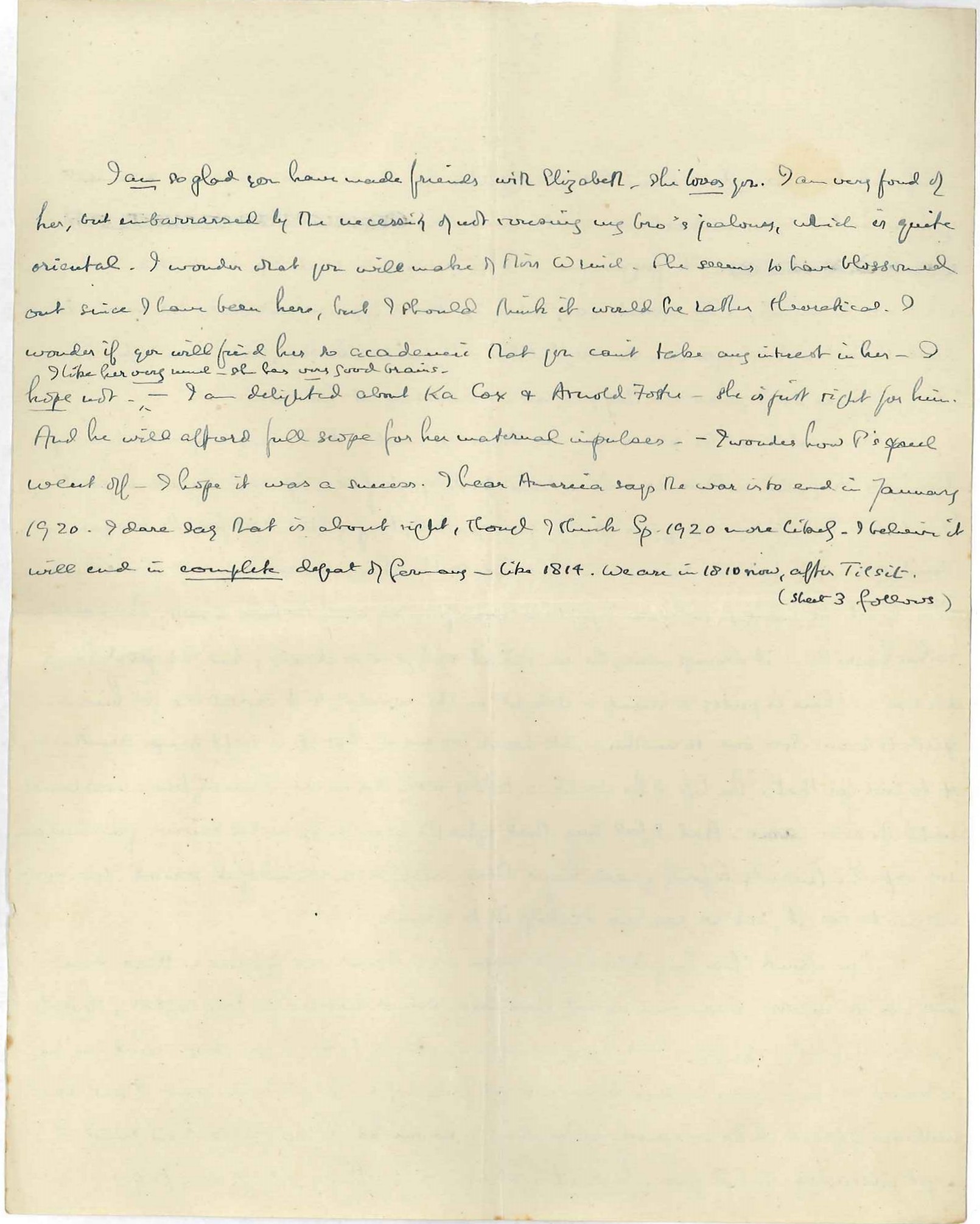

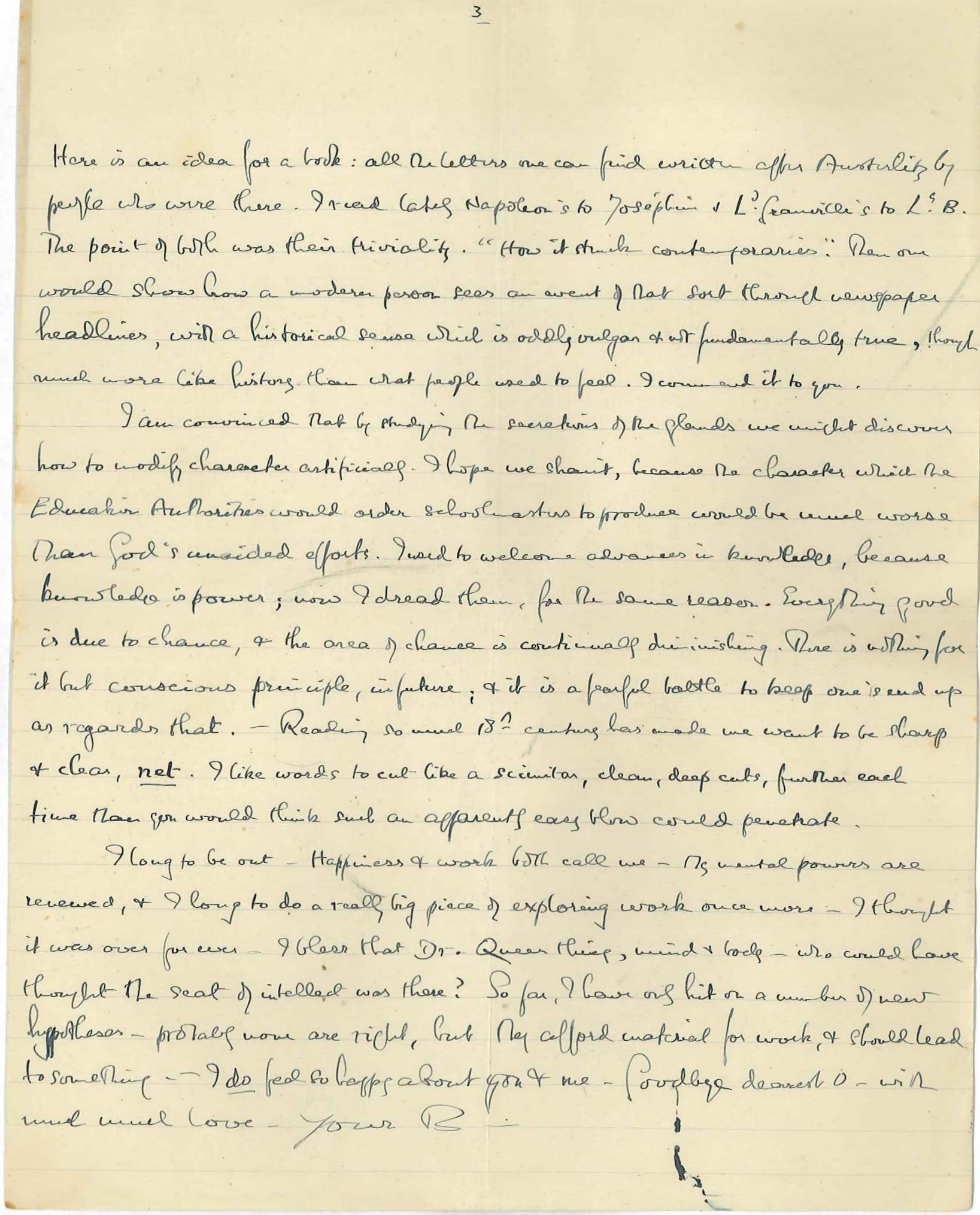

Here is an idea for a book: all the letters one can find written after Austerlitz12 by people who were there. I read lately Napoleon’s to Joséphine13 and Ld. Granville’s to Ly. B.14 The point of both was their triviality. “How it struck contemporaries.” Then one would show how a modern person sees an event of that sort through newspaper headlines, with a historical sense which is oddly vulgar and not fundamentally true, though much more like history than what people used to feel. I commend it to you.

I am convinced that by studying the secretions of the glands we might discover how to modify character15 artificially. I hope we shan’t, because the character which the Education Authorities would order schoolmasters to produce would be much worse than God’s unaided efforts. I used to welcome advances in knowledge, because knowledge is power; now I dread them, for the same reason. Everything good is due to chance, and the area of chance is continually diminishing. There is nothing for it but conscious principle, in future; and it is a fearful battle to keep one’s end up as regards that. — Reading so much 18th century has made me want to be sharp and clear, net.16 I like words to cut like a scimitar, clean, deep cuts, further each time than you would think such an apparently easy blow could penetrate.

I long to be out. Happiness and work both call me. My mental powers are renewed, and I long to do a really big piece of exploring work once more. I thought it was over for ever. I bless that Dr. Queer thing, mind and body — who could have thought the seat of intellect17 was there? So far, I have only hit on a number of new hypotheses — probably none are right, but they afford material for work, and should lead to something. — I do feel so happy about you and me. Goodbye dearest O — with much much love.

Your

B.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from a digital scan of the initialled original in BR’s hand in the Morrell papers at the University of Texas at Austin. Sheet 3 was associated with Letter 61, but it clearly belongs here, in the discussion of the Napoleonic wars. The letter was published as #318 in Vol. 2 of BR’s Selected Letters.

- 2

your letter Ottoline’s letter of 30 July 1918 (BRACERS 114752).

- 3

I hate all the Bloomsbury crew … down on S.S J. Middleton Murry (representing Bloomsbury in BR’s eyes) had recently published a negative review of Siegfried Sassoon’s Counter-Attack and Other Poems, to which both BR (Letter 39) and Philip Morrell wrote letters to the editor of The Nationin reply. On 30 July 1918 Ottoline reported to BR that the Bloomsberries were “very angry” with her husband for criticizing Murry’s assessment of Sassoon’s poetry. Several painters and writers associated with the group, for which Ottoline’s Garsington Manor had become a prized retreat, are mentioned in BR’s prison letters. Most individuals were either friendly or neutral, and Ottoline assured BR a few days later that “All here talk of you every few hours and all Love, adore and worship you! Quite true this is” (4 Aug. 1918, BRACERS 114753). Lytton Strachey was the only Bloomsbury figure so identified in Ottoline’s account of the group’s defence of Murry (30 July 1918, BRACERS 114752). According to Bloomsbury scholar S.P. Rosenbaum, BR’s distaste for the “Bloomsbury crew” may have extended to the Woolfs and “probably” to Virginia’s brother-in-law, Clive Bell, as well as J.M. Keynes. The art critic Bell nevertheless captured the essence of his group’s somewhat ambiguous relationship to BR, who “though no one has ever called him ‘Bloomsbury’ appeared to be a friend and was certainly an influence” (quoted in Rosenbaum, “Bertrand Russell in Bloomsbury”, Russell 4 [1984]: 26).

- 4

feel as you do about Julian Ottoline’s letter to BR of 30 July 1918 (which she probably delivered discreetly during her prison visit the next day), complained that her daughter, Julian Ottoline Morrell (later Goodman, then Vinogradoff, 1906–1989), had returned home “in rather a difficult mood, very contradictory and gruff and disobeying.… Julian has a dreadfully depressing effect on me. I feel it is all my own incapacity that makes her so tiresome” (BRACERS 114752). Julian, the previous year, had been sent to Lucy Silcox’s school, St. Felix, Southwold.

- 5

hard and <un>feeling BR wrote “hard and feeling”. He must have meant “unfeeling”, and SLBR printed “[un]feeling” (at 2: 166).

- 6

Chinese doctrine of Tao One concept associated with the Chinese philosopher Laozi (fl. 6th century BC) was that there was an ineffable way (tao) that the world both ought to be and, in some sense, was, and that one must recognize this and live in harmony with it. Almost every school of Chinese philosophy had some doctrine of tao, and it would be rash to impute a precise doctrine to BR. The general idea he alludes to here is that one can find one’s tao, not by striving to do so, but by following one’s spontaneous inclinations. It is not known when Ottoline took umbrage at BR’s praise of Taoism, but in September 1914 she had sent him a translation by Lionel Giles of the creed’s semi-mythical founder (The Sayings of Lao-Tze [London: John Murray, 1905]). One such saying by Laozi appeared on the title-page of BR’s forthcoming book, Roads to Freedom (1918): “Production without possession, action without self-assertion, development without domination.”

- 7

I wonder … Miss Wrinch BR’s former logic student Dorothy Wrinch made a highly favourable impression on Ottoline after arriving at Garsington Manor for a visit on 30 July 1918. Indeed, she assured BR that “Miss W. is loved by us all” (4 Aug. 1918, BRACERS 114753).

- 8

Ka Cox and Arnold Foster Katherine (“Ka”) Laird Cox (1887–1938). Before the war, as a student at Cambridge, she had been one of the group of “Neo-Pagans” around Rupert Brooke, with whom she fell in love. In September 1918 she married William Arnold-Forster (1885–1951), a painter in the Royal Naval Reserve.

- 9

P’s speechPhilip Morrell had prepared a speech for the Commons’ adjournment debate of Allied war aims on 8 August. But he never delivered it because the discussion, on the last day of the parliamentary session, was foreshortened by James Lowther, the Conservative Speaker of the House. Lowther was considered by Ottoline as “unfair to Pacifists” (to BR, 11 Aug. 1918, BRACERS 114754). On 30 July 1918 she told BR that Philip was “making a speech for tomorrow on Vote of Credit” (BRACERS 114752), but did not speak on that occasion either.

- 10

complete defeat of Germany — like 1814 BR is referring not to Germany’s “complete defeat” 104 years previously but, rather, to that of Napoleonic France. Indeed, a revitalized Prussia was a key member of the anti-French coalition that forced Napoleon’s abdication and exile in April 1814. Although a depleted French army continued to achieve battlefield success in the War of the Sixth Coalition (1813–14), France’s overall military position had become unsustainable. Starting with German Social Democracy (London: Longmans, Green, 1896, p. 43), Russell often referred to this late phase of the Napoleonic Wars as Prussia’s “war of liberation” — in connection with the rise of a German nationalism stimulated by earlier military defeats inflicted by France.

- 11

Tilsit The collaboration between France and Russia which began with the Treaty of Tilsit in 1807 ended in 1810 when Russia withdrew from Napoleon’s blockade of Britain.

- 12

Austerlitz The Battle of Austerlitz (1805), one of Napoleon’s great victories, in which he decisively defeated Austria and Russia.

- 13

Napoleon’s to Joséphine His letters of 3, 5, and 7 December 1805. For a contemporary English edition, see Letters to Josephine, 1796–1812, ed. Henry Foljambe Hall (London: J.M. Dent, 1901).

- 14

Ld. Granville’s to Ly. B. “Bessborough.” (BR’s note at BRACERS 119460 for Letter 40: see notes 9 and 10 there.) See Lord Granville, Private Correspondence, 1781–1821 (London: J. Murray, 1917), 2: 151–2 (letter of 6 Dec. 1805).

- 15

secretions of the glands … modify character BR’s prison reading included Walter B. Cannon’s pioneering inquiry into the physiology of emotions: Bodily Changes in Pain, Hunger, Fear and Rage: an Account of Recent Researches into the Function of Emotional Excitement (New York and London: D. Appleton, 1916). In “On ‘Bad Passions’” (written in prison; 19 in Papers 8), BR cited Cannon’s work, saying it suggested “immense possibilities” in changing character. In a 1920 review (5 in Papers 9), he praised the “epoch-making researches” of this American neurologist and Harvard professor of physiology. He included a longer commentary on them in The Analysis of Mind (London: Allen & Unwin, 1921), pp. 280–3, and drew attention to the possibilities of character modification in works up to at least 1931 (The Scientific Outlook (London: Allen & Unwin), p. 188.

- 16

net French for “clear-cut”, “distinct”.

- 17

bless thatDr. … seat of intellect “Who cured me of piles.” (BR’s note at BRACERS 119466.) The doctor was Elizabeth Russell’s brother Sydney Beauchamp (see note 7 to Letter 15).

Textual Notes

Annotations by BR

In the late 1940s, when BR was going through his archives, and in the 1950s when he was revising his Autobiography, he would occasionally annotate letters. He did this to sixteen of the Brixton letters. Links to them are gathered here for convenient access to these new texts. In the annotations to the letters they are always followed by “(BR’s note.)”

Letter 2, note 5 happy.

5, note 6 congratulations to G.J.

9, note 28 bit of Girondin history.

12, note 6 friend.

15, note 2 (the letter in general).

20, note 7 G.J.

31, note 3 Dr’s treatment.

40, notes 9, 10 Ld. G.L.G, Lady B’s.

44, note 14 S.S.

48, note 48 Mother Julian’s Bird.

57, notes 13, 16 Ld. Granville’s to Ly. B., bless that Dr. … seat of intellect.

70, note 15 Mrs Scott.

73, note 12 E.S.P. Haynes.

76, note 4 Cave.

85, note 2 Marsh on Rupert.

102, notes 23, 28 Woolley, K. Lonsdale.

General Annotations

Brett note from Auto. 2: 93

Cousens note from Auto. 2: 71

Kyle note with her letters to BR

Rinder note from Auto. 2: 88n.

Silcox note on BRACERS 80365

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Dorothy Wrinch

Dorothy Maud Wrinch (1894–1976), mathematician, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. She studied mathematics and philosophy at Girton College, Cambridge, and came under BR’s influence in her second year when she took his course on mathematical logic. She taught mathematics at University College, London, 1918–21, and then at Oxford, 1922–30. Her first publications were in mathematical logic and philosophy, and during the 1920s she wrote on the philosophy of science. But in the 1930s her interests turned to mathematical biology and crystallography, and in 1935 she moved to the United States on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship and remained there for the rest of her life. Unfortunately, as a biologist she is best known for a long and stubborn controversy with Linus Pauling about the structure of proteins in which he was right and she was wrong. See Marjorie Senechal, I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science (New York: Oxford U. P., 2013). Chapter 7 is devoted to Wrinch’s interactions with BR in Brixton.

Elizabeth Russell

Elizabeth Russell, born Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941), was a novelist who in 1891 married Graf von Arnim-Schlagenthin. She became known as “Elizabeth”, the name she used in publishing Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898), and she remained widely known as Elizabeth von Arnim, although the Library of Congress catalogues her as Mary Annette (Beauchamp), Countess von Arnim. She was a widow when she married BR’s brother, Frank, on 11 February 1916. The marriage was quickly in difficulty; she left it for good in March 1919, but they were never divorced and she remained Countess Russell (becoming Dowager Countess after Frank’s death in 1931).

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).

J. Middleton Murry

J. Middleton Murry (1889–1957), critic and editor, was educated in classics at Brasenose College, Oxford, before establishing in 1911 the short-lived avant-garde journal, Rhythm. In May 1918 he married the author Katherine Mansfield, to whose literary legacy he became devoted after her death from tuberculosis only five years later. The couple were frequent visitors to Garsington Manor, and Murry appears at one time to have had a romantic yearning for Ottoline (see note to Letter 48). Although Murry’s scornful treatment of Sassoon’s poetry annoyed BR (see Letter 39), he became, nevertheless, a frequent contributor to The Athenaeum during Murry’s two-year stint as its editor (1919–21). After the ailing literary weekly merged with The Nation in 1921, Murry continued his vigorous promotion of modernism in the arts from the helm of his own monthly journal, The Adelphi, which he edited for 25 years. During the First World War he worked as a translator for the War Office but became an uncompromising pacifist in the 1930s. One of the last assignments of his journalistic career was as editor of the pacifist weekly, Peace News (1940–46). Source: Oxford DNB.

J.E. Littlewood

John Edensor Littlewood (1885–1977), mathematician. In 1908 he became a fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, and remained one for the rest of his life. In 1910 he succeeded Whitehead as college lecturer in mathematics and began his extraordinarily fruitful, 35-year collaboration with G.H. Hardy. During the First World War he worked on ballistics for the British Army. He and BR were to share Newlands farm, near Lulworth, during the summer of 1919. Littlewood had two children, Philip and Ann Streatfeild, with the wife of Dr. Raymond Streatfeild.

Lucy Silcox

Lucy Mary Silcox (1862–1947), headmistress of St. Felix school in Southwold, Suffolk (1909–26), feminist, and long-time friend of BR’s, whom he had known since at least 1906. On a letter from her, he wrote that she was “one of my dearest friends until her death ” (BR’s note, BRACERS 80365). After learning of BR’s conviction and sentencing by the Bow St. magistrate, a distraught Silcox reported to him that she had been “shut out in such blackness and desolation” (2 Feb. 1918, BRACERS 80377). During BR’s imprisonment it was Silcox who brought to his attention the Spectator review of Mysticism and Logic. Years later (in 1928), when BR and Dora Russell had launched Beacon Hill School, Silcox came with Ottoline Morrell to visit it.

Lytton Strachey

Lytton Strachey (1880–1932), biographer, reviewer and a quintessential literary figure of the Bloomsbury Group. He is best known for his debunking portraits of Cardinal Manning, Florence Nightingale, Dr. Arnold and General Gordon, published together as Eminent Victorians (London: Chatto & Windus, 1918; Russell’s library), which BR read in Brixton with great amusement as well as some critical reservations (see Letter 7). Although Strachey was homosexual, he and the artist Dora Carrington were devoted to each other and from 1917 lived together in Tidmarsh, Berkshire. BR had become acquainted with the somewhat eccentric Strachey, a fellow Cambridge Apostle, while his slightly younger contemporary was reading history at Trinity College. He admired Strachey’s literary gifts, but doubted his intellectual honesty. Almost three decades later BR fleshed out the unflattering thumbnail of Strachey drawn for Ottoline in Letter 7, in a “Portrait from Memory” for BBC radio. Strachey was “indifferent to historical truth”, BR alleged in that broadcast, “and would always touch up the picture to make the lights and shades more glaring and the folly or wickedness of famous people more obvious” (The Listener 48 [17 July 1952]: 98). Main biography: Michael Holroyd, Lytton Strachey: a Critical Biography, 2 vols. (London: Heinemann, 1967–68).

Philip Morrell

Philip Morrell, Ottoline’s husband (1870–1943), whom she had married in 1902 and with whom, four years later, she had twins — Julian, and her brother, Hugh, who died in infancy. The Morrells were wealthy Oxfordshire brewers, although Philip’s father was a solicitor. He won the Oxfordshire seat of Henley for the Liberal Party in 1906 but held this Conservative stronghold only until the next general election, four years later. For the second general election of 1910 he ran successfully for the Liberals in the Lancashire manufacturing town of Burnley. But Morrell’s unpopular anti-war views later cost him the backing of the local Liberal Association, and his failure to regain the party’s nomination for the post-war election of 1918 (see Letter 89) effectively ended his short political career. Unlike many other Liberal critics of British war policy (including BR), Morrell did not transfer his political allegiance to the Labour Party. Although Ottoline and her husband generally tolerated each other’s extra-marital affairs, a family crisis ensued when in 1917 Philip impregnated both his wife’s maid and his secretary (see Letter 48).

Rupert Brooke

Rupert Chawner Brooke (1887–1915), poet and soldier, became a tragic symbol of a generation doomed by war after he died from sepsis en route to the Gallipoli theatre. Although BR had previously expressed a dislike, even loathing, of Brooke in letters to Ottoline, he too placed him in this tragic posthumous light. Rupert “haunts one always”, he wrote Ottoline shortly after the poet’s death in April 1915, and (five months later) “one is made so terribly aware of the waste when one is here [Trinity College]…. Rupert Brooke’s death brought it home to me” (BRACERS 18431, 18435: see also Letter 85). Brooke had become acquainted with BR and members of the Bloomsbury Group in pre-war Cambridge. BR was an examiner of Brooke’s King’s College fellowship dissertation (later published as John Webster and the Elizabethan Drama [1916]), with which he was pleasantly and surprisingly impressed. “It is astonishingly well-written, vigorous, fertile, full of life”, he reported to Ottoline in February 1912 (BRACERS 17447). After the outbreak of war Brooke obtained a commission in a naval reserve unit attached to a military combat battalion; his war poetry captures the patriotic idealism that compelled so many young men to enlist.

Siegfried Sassoon

Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967), soldier awarded the MC and anti-war poet. Ottoline had befriended him in 1916, and the following year, when Sassoon refused to return to his regiment after being wounded, she and BR helped publicize this protest, which probably saved him from a court martial. BR even assisted Sassoon in revising his famous anti-war statement, which was read to the House of Commons by a Liberal M.P. on 30 July 1917. Sassoon’s actions were an embarrassment to the authorities, for he was well known as both a poet and a war hero. Unable to hush the case up, the government acted with unexpected subtlety and declared Sassoon to be suffering from shell-shock and sent him to Craiglockhart War Hospital for Officers, near Edinburgh. After a period of recuperation in Scotland overseen by military psychiatrist Capt. W.H.R. Rivers, Sassoon decided to return to the Front (see Jean Moorcroft Wilson, Siegfried Sassoon: Soldier, Poet, Lover, Friend [New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2014]). He was again wounded in July 1918 and was convalescing in Britain during some of BR’s imprisonment. Although each admired the other’s stand on the war, BR and Sassoon were never close in later years. Yet Sassoon did pledge £50 to the fellowship plan fund (see BRACERS 114758), and decades later he donated a manuscript in support of BR’s International War Crimes Tribunal (see BRACERS 79066).

The Nation

A political and literary weekly, 1907–21, edited for its entirety by H.W. Massingham before it merged with The Athenaeum and then The New Statesman. BR regularly contributed book reviews, starting in 1907. During his time at Brixton, he published there a book review (14 in Papers 8; mentioned in Letters 4 and 102) and a letter to the editor (Letter 39). In August 1914 The Nation hastily abandoned its longstanding support for British neutrality, rejecting an impassioned defence of this position written by BR on the day that Britain declared war (1 in Papers 13). For the next two years the publication gave its editorial backing (albeit with mounting reservations) to the quest for a decisive Allied victory. At the same time, it consistently upheld civil liberties against the encroachments of the wartime state, and by early 1917 had started calling for a negotiated peace as well. The Nation had recovered its dissenting credentials, but for allegedly “defeatist” coverage of the war was hit with an export embargo imposed in March 1917 by Defence of the Realm Regulation 24B.

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.