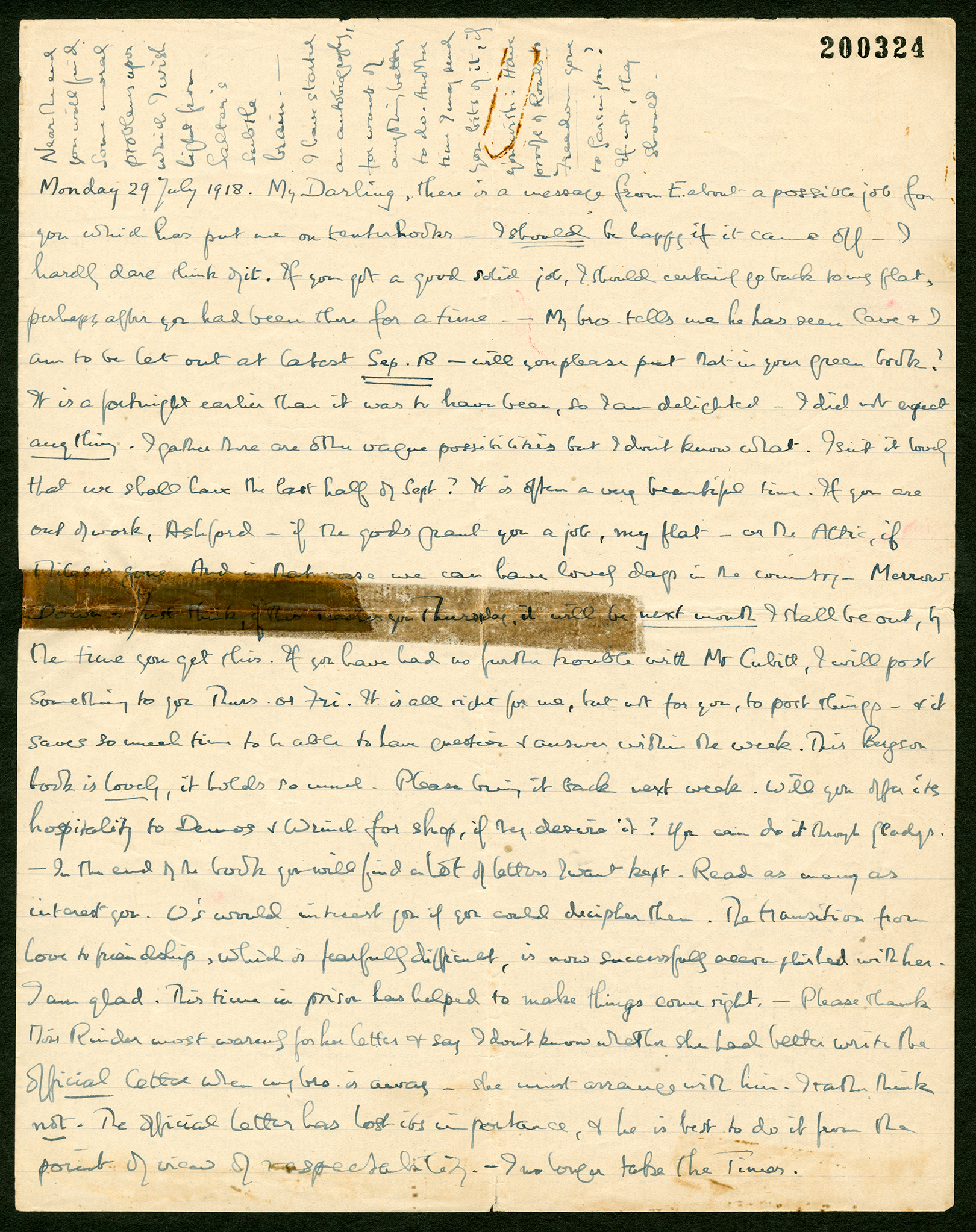

Brixton Letter 52

BR to Constance Malleson

July 29, 1918

- AL

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-52

BRACERS 19337

<Brixton Prison>1

Monday 29 July 1918.

My Darling, there is a message2 from E. about a possible job for you which has put me on tenterhooks. I should be happy if it came off. I hardly dare think of it. If you got a good solid job, I should certainly go back to my flat, perhaps after you had been there for a time. — My brother tells me he has seen Cave and I am to be let out at latest Sep. 183 — will you please put that in your green book? It is a fortnight earlier than it was to have been, so I am delighted. I did not expect anything. I gather there are other vague possibilities but I don’t know what. Isn’t it lovely that we shall have the last half of Sept? It is often a very beautiful time. If you are out of work, Ashford — if the gods grant you a job, my flat — or the Attic, if Miles is gone. And in that case we can have lovely days in the country — Merrow Down.4 Just think, if this reaches you Thursday, it will be next month I shall be out, by the time you get this. If you have had no further trouble with Mr Cubitt, I will post something to you5 Thurs. or Fri. It is all right for me, but not for you, to post things6 — and it saves so much time to be able to have question and answer within the week. This Bergson book is lovely, it holds so much.7 Please bring it back next week. Will you offer its hospitality to Demos and Wrinch for shop,8 if they desire it? You can do it through Gladys. — In the end of the book you will find a lot of letters I want kept.9 Read as many as interest you. O’s10 would interest you if you could decipher them. The transition from love to friendship, which is fearfully difficult, is now successfully accomplished with her. I am glad. This time in prison has helped to make things come right. — Please thank Miss Rinder most warmly for her letter11 and say I don’t know whether she had better write the official letter when my brother is away — she must arrange with him. I rather think not. The official letter12 has lost its importance, and he is best to do it from the point of view of respectability. — I no longer take the Times.13

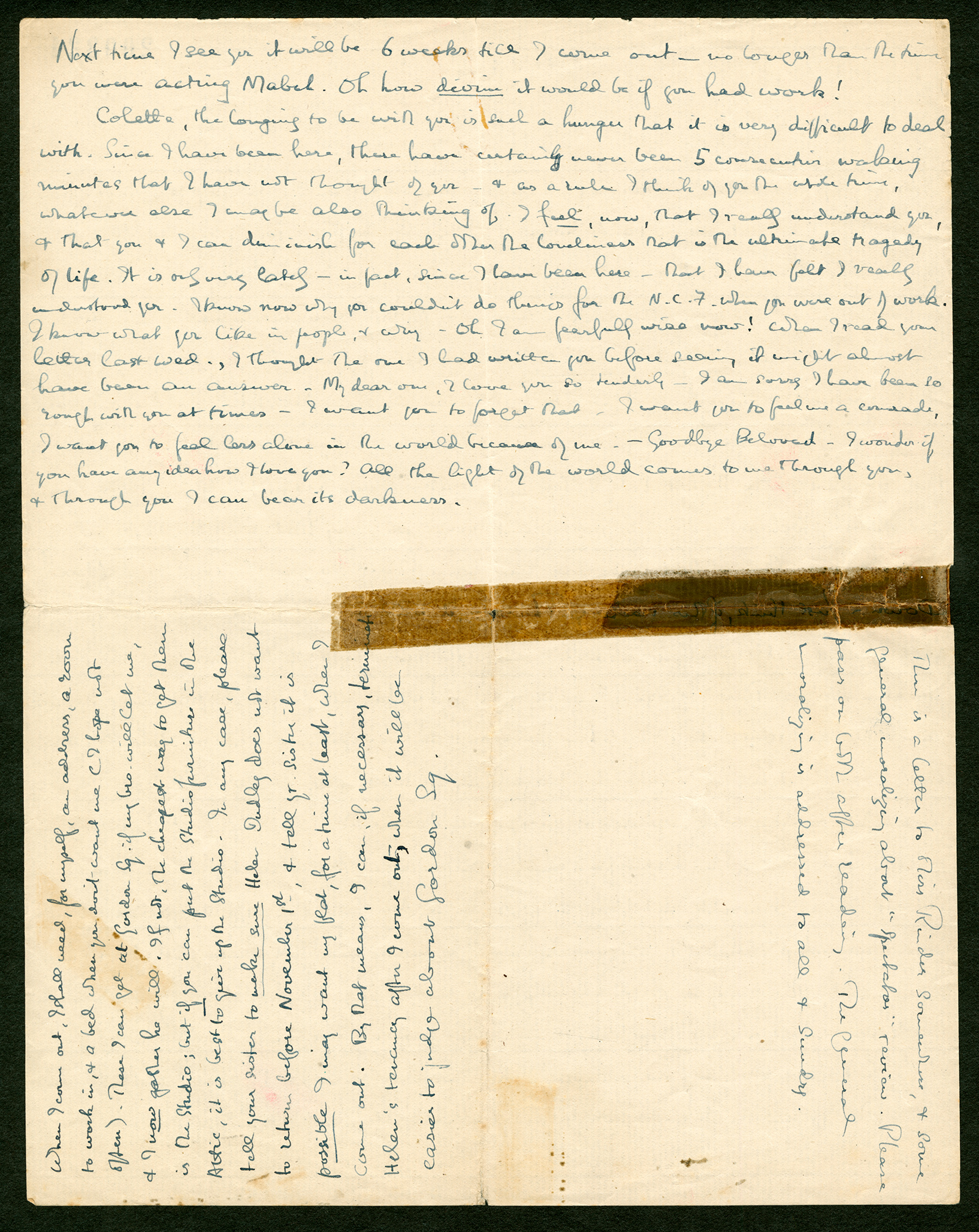

Next time I see you it will be 6 weeks till I come out14 — no longer than the time you were acting Mabel.15 O how divine it would be if you had work!

Colette, the longing to be with you is such a hunger that it is very difficult to deal with. Since I have been here, there have certainly never been 5 consecutive waking minutes that I have not thought of you — and as a rule I think of you the whole time, whatever else I may be also thinking of. I feel, now, that I really understand you, and that you and I can diminish for each other the loneliness that is the ultimate tragedy of life. It is only very lately — in fact, since I have been here — that I have felt I really understood you. I know now why you couldn’t do things for the N.C.F. when you were out of work.16 I know what you like in people, and why. Oh I am fearfully wise now! When I read your letter last Wed., I thought the one I had written you before17 seeing it might almost have been an answer. My dear one, I love you so tenderly. I am sorry I have been so rough with you at times — I want you to forget that. I want you to feel me a comrade,18 I want you to feel less alone in the world because of me. — Goodbye Beloved. I wonder if you have any idea how I love you? All the light of the world comes to me through you, and through you I can bear its darkness.

Near the end you will find some moral problems upon which I wish light from Salter’s subtle brain.19,a — I have started an autobiography,20 for want of anything better to do. Another time I may send you bits of it, if you wish. Have proofs of Roads to Freedom gone to Garsington?21 If not, they should.

When I come out,b I shall need, for myself, an address, a room to work in, and a bed when you don’t want me (I hope not often). These I can get at Gordon Sq. if my brother will let me, and I now gather he will. If not, the cheapest way to get them is the Studio; but if you can put the Studio furniture in the Attic, it is best to give up the Studio. In any case, please tell your sister to make sure Helen Dudley22 does not want to return before November 1st, and tell your sister23 it is possible I may want my flat, for a time at least, when I come out. By that means, I can, if necessary, terminate Helen’s tenancy after I come out, when it will be easier to judge about Gordon Sq.

There is a letter to Miss Rinderc somewhere, and some general moralizing about Spectator review.24 Please pass on both after reading. The general moralizing is addressed to all and sundry.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the unsigned, handwritten original in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. It was folded twice, at first allowing for the exposed quarters of the sheet to be blank. Then BR wrote on them. The sheet was mended with, unfortunately, cellotape.

- 2

a message The message from Elizabeth Russell about Colette is contained in Frank’s letter to BR, 23–25 July 1918 (BRACERS 46929). Elizabeth noted that Colette had the prospect of a three-year engagement in London and was “delighted and excited” about it. No further details are known, and the unlikely long engagement for a struggling actress (or any actress, for that matter) did not come off. This could be an oblique reference to the Experimental Theatre. In her letter to BR of 28 July (BRACERS 113146), Colette mentioned that “E. subscribed generously” to it.

- 3

My brother… seen Cave …Sep. 18 If BR had served his full sentence of six months, he would have been let out at the beginning of November; but from at least 22 June (see note 7 at Letter 24) he expected to be released a month early, on or about 2 October. For a short time, BR expected release on 18 September, i.e. six weeks earlier than the original sentence of 2 November. Frank, in his letter of 23–26 July 1918 (BRACERS 46929) wrote: “Saw Cave this afternoon — am authorised to say you shall have 6 weeks remission for work: the rest he will ‘think about’” (BRACERS 46929). However, this was a verbal promise, perhaps even a misunderstanding. When Frank pushed for an even earlier release of early August in his letter to the Home Secretary on 29 July BRACERS 57181), Sir George Cave replied on 5 August (BRACERS 57178) granting a release date at the end of September. BR told Ottoline and Colette on 8 August it was a “blow” (Letters 61 and 62, respectively). Cave, understanding the disappointment expressed by Frank, wrote in his next letter: “I intend to re-consider the matter towards the end of August; but I am unwilling that your brother should be told this, as I must keep a free hand” (11 Aug. 1918, BRACERS 57182). In fact, BR was released at an earlier date, on 14 September. His philosophical industry in prison as well as good conduct earned him “full marks”.

- 4

Merrow Down This was a favourite walk. Colette and BR took their first walk to Merrow Down, Surrey, in early December 1916; what was so important about this first walk is not known. However, BR recollected the day in letters he wrote c.14 April 1917 (BRACERS 19148) and on 3 December 1920 from Peking (BRACERS 19714) in which he noted that “it is almost exactly 4 years” since their first walk there. Colette mentioned meeting Roger Fry on the fringe of Merrow Down when she and BR were setting out for a walk (In the North [London: Gollancz, 1946], p. 149). She also recalls the walk from Dorking to Merrow Down as her favourite among the many country walks that they took (After Ten Years [London: Cape, 1931], p. 124).

- 5

no further trouble with Mr Cubitt, I will post something to you Once BR found out that a Scotland Yard detective had been to Colette’s home investigating the Personals she had placed in The Times, he wrote that he would stop posting her letters. By that he meant putting a letter in a wrapper inside a book indicating that the letter should be mailed to her. The alternative was that the letter would be hand delivered by someone. “Ireland Cubitt” was BR’s code name for the man, first used on 20 July 1918 (see note 5 to Letter 42).

- 6

all right for me, but not for you, to post things Some of the letters that BR concealed in books were put into the postal system by Frank, Gladys Rinder or others, as Colette commented in her correspondence that letters arrived from him via the post. In her letter of 18 July 1918 (BRACERS 113143), she wrote that a letter from him had just arrived but she had to put it in her handbag and go off to a luncheon. Only afterwards could she tear it open and read it. However, it would be impossible for her to mail anything to him, as he could only officially get one letter per week. Presumably BR was just stating the obvious in his remark.

- 7

Bergson book is lovely, it holds so much Smuggled correspondence is what this “camouflage book” could hold in abundance. See Letter 51. These are possibly the only circumstances under which BR would describe a Bergson book as “lovely”. The particular book cannot be identified with any of the Bergson titles in Russell’s library, for none of them had any uncut pages upon arrival at McMaster.

- 8

its hospitality to Demos and Wrinch for shop During the last six weeks of his imprisonment BR received at least six smuggled letters from his former logic student Dorothy Wrinch, although this correspondence was far from exclusively technical. No prison letters from Raphael Demos are extant, but he evidently talked “shop” when he visited BR in Brixton on 14 August. In Letter 70 BR lamented (but excused) the inability of his former students to grasp the philosophy he was developing in prison: “From what she <Wrinch> writes and Demos says, I see they don’t understand the new ideas I am at. It is no wonder, as my ideas are still rather vague.”

- 9

letters I want kept BR was referring to letters that had been sent to him in prison — he decided that it was too risky to keep them in his cell, so he smuggled them back out.

- 10

O’s Ottoline Morrell’s handwriting is notoriously hard to read.

- 11

for her letterRinder’s letter cannot be identified.

- 12

official letter BR was allowed to send and receive one official letter per week.

- 13

I no longer take the Times. BR no longer had a need to take the Times as Colette was no longer placing messages to him in the Personals. Her last such message was on 27 June 1918 (BRACERS 96085). He seems to have read the Daily News instead.

- 14

6 weeks till I come out This projects a release time of mid-September 1918. BR was confident that his brother, Frank, would be able to secure this earlier than expected release. See note 3 above on “Sep. 18”.

- 15

acting Mabel Colette had been in Manchester and then York and Scarborough for most of May and early June 1918, touring in a play called Phyl (author unknown) and playing the role of Mabel.

- 16

why you couldn’t do things for the N.C.F. when you were out of work Colette did not act in London from mid-August 1916 until May 1918. However, in 1917 she acted in two film roles, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton. These roles took her out of town for long stretches of time. “I saw less and less of B.R. and the N.C.F., and more and more of the people I was working with” (After Ten Years [London: Cape, 1931], p. 122). She was doing less for the N.C.F., not because she was out of work, but because she had work.

- 17

one I had written you before Possibly it was Letter 46.

- 18

to feel me a comrade BR often called Colette his “heart’s comrade”.

- 19

Near the end … some moral problems … Salter’s subtle brain The letter it refers to begins: “I have been thinking out some casuistical conundrums which I desire to submit to the collective wisdom of the National Committee ...” (Letter 54). BR’s successor as Acting Chairman of the NCF, Dr. Alfred Salter was an “absolutist” in matters of conscientious objection.

- 20

started an autobiography BR’s final Autobiography was not published until 1967–69 (3 vols.). The earliest extant draft is “My First Fifty Years”, dictated in 1931. Nothing further is known of this prison attempt at a memoir, and the pages he wrote must have been destroyed. An autobiography BR started during his affair with Ottoline met a similar fate.

- 21

proofs of Roads to Freedom… Garsington BR had completed the writing of this book before he went to prison. He wanted proofs sent to the country home of Lady Ottoline and Philip Morrell so Ottoline could read what she hadn’t heard him read aloud (Letter 61).

- 22

Helen Dudley An American from Chicago with whom BR became involved during his 1914 trip to the United States. She followed him back to London, was rebuffed by him, and ended up renting his Bury Street flat in late 1916 or early 1917. In May 1918 she sublet the flat to Clare Annesley.

- 23

your sister Clare Annesley (1893–1980), artist.

- 24

some general moralizing about Spectator review I.e., Letter 53.

Textual Notes

- a

Near the end … some moral problems … Salter’s subtle brain (This paragraph was written in the top margin.)

- b

When I come out The paragraph was added sideways on a blank quarter (when folded) of the verso of the sheet.

- c

There is a letter to Miss Rinder The paragraph was added sideways (and upside-down to the previous addition) on the other blank quarter of the verso of the sheet. The letter seems not to be extant, if it was indeed distinct from the “general moralizing”.

57 Gordon Square

The London home of BR’s brother, Frank, 57 Gordon Square is in Bloomsbury. BR lived there, when he was in London, from August 1916 to April 1918, with the exception of January and part of February 1917.

Boismaison

Colette and BR vacationed at a house, The Avenue, owned by Mrs. Agnes Woodhouse and her husband, in the countryside near Ashford Carbonel, Shropshire, in August 1917. They nicknamed the house “Boismaison”. Agnes Woodhouse took in paying guests. Their first visit was idyllic. They returned for other vacations — in 1918 before he entered prison and in April 1919. Their plan to go soon after he got out of prison failed because their relationship faltered for a time. They discussed returning in the summer of 1919 — a booking was even made for 12–19 July — but in the end they didn’t go. See S. Turcon, “Then and Now: Bertie and Colette’s Escapes to the Peak District and Welsh Borderlands”, Russell 34 (2014): 117–30.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Dorothy Wrinch

Dorothy Maud Wrinch (1894–1976), mathematician, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. She studied mathematics and philosophy at Girton College, Cambridge, and came under BR’s influence in her second year when she took his course on mathematical logic. She taught mathematics at University College, London, 1918–21, and then at Oxford, 1922–30. Her first publications were in mathematical logic and philosophy, and during the 1920s she wrote on the philosophy of science. But in the 1930s her interests turned to mathematical biology and crystallography, and in 1935 she moved to the United States on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship and remained there for the rest of her life. Unfortunately, as a biologist she is best known for a long and stubborn controversy with Linus Pauling about the structure of proteins in which he was right and she was wrong. See Marjorie Senechal, I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science (New York: Oxford U. P., 2013). Chapter 7 is devoted to Wrinch’s interactions with BR in Brixton.

Dr. Alfred Salter

Dr. Alfred Salter (1873–1945), socialist and pacifist physician, replaced BR as Acting Chairman of the NCF in January 1918. For two decades he had been dedicated both professionally and politically to the working-class poor of Bermondsey. In 1898 Salter moved there into a settlement house founded by the Rev. John Scott Lidgett to minister to the health, social and educational needs of this chronically deprived borough in south-east London. In establishing a general practice in Bermondsey, Salter forsook the very real prospect of advancement in the medical sciences (at which he had excelled as a student at Guy’s). Shortly after his marriage to fellow settlement house worker Ada Brown in 1900, the couple joined the Society of Friends and Salter became active in local politics as a Liberal councillor. In 1908 he became a founding member of the Independent Labour Party’s Bermondsey branch and twice ran for Parliament there under its banner before winning the seat for the ILP in 1922. Although he lost it the following year, he was again elected in October 1924 and represented the constituency for the last twenty years of his life, during which he remained a consistently strong pacifist voice inside the ILP. Salter was an indefatigable organizer whose steely political will and fixed sense of purpose made him, in BR’s judgement, inflexible and doctrinaire when it came to the nuances of conscientious objection. See Oxford DNB and A. Fenner Brockway, Bermondsey Story: the Life of Alfred Salter (London: Allen & Unwin, 1949).

Elizabeth Russell

Elizabeth Russell, born Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941), was a novelist who in 1891 married Graf von Arnim-Schlagenthin. She became known as “Elizabeth”, the name she used in publishing Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898), and she remained widely known as Elizabeth von Arnim, although the Library of Congress catalogues her as Mary Annette (Beauchamp), Countess von Arnim. She was a widow when she married BR’s brother, Frank, on 11 February 1916. The marriage was quickly in difficulty; she left it for good in March 1919, but they were never divorced and she remained Countess Russell (becoming Dowager Countess after Frank’s death in 1931).

Experimental Theatre

Colette first mentioned that she and Miles were trying to start an Experimental Theatre in a letter of 24 June 1918 (BRACERS 113135), indicating that Miles would earn a tiny income from it. About a month later, she wrote that Elizabeth Russell had subscribed generously to the Theatre and that £700 had been raised, but hundreds still had to be found (BRACERS 113146). A few days later she wrote that Captain Stephen Gordon, a north-country lawyer working for the government, was to be the honorary treasurer, noting that he had “put most of the drive into the whole thing” (BRACERS 113147). During August Colette was happy with her involvement with the Theatre (Letter 68). John Galsworthy came to tea to discuss the project (c.14 Aug., BRACERS 113149). On 2 September she listed the members of the Theatre committee as “Desmond <MacCarthy>, Massingham, Galsworthy, and Dennis (Bradley)” (BRACERS 113155). The following day she wrote that she was learning three parts (BRACERS 113156). In her memoirs, Colette wrote about the “Experimental Little Theatre” but dated it 1919 (After Ten Years [London: Cape, 1931], pp. 129–30). An “artistic” theatre did get founded in 1920 in Hampstead, and John Galsworthy was connected to that venture, The Everyman Theatre — he was part of a reading committee which chose the works to be performed (The Times, 9 Sept. 1919, p. 8). The Everyman Theatre was under the direction of Norman MacDermott. In his book Everymania (London: Society for Theatre Research, 1975), he noted that he met Miles in the summer of 1918: they rented a store in Bloomsbury, had a cabinetmaker build sets, and put on plays with actors “bored with West-End theatres” (p. 10). It is likely that the Everyman Theatre was an out-growth of the Experimental Theatre.

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Heart’s Comrade

Colette first called BR her “heart’s comrade” in her letter of 17 November 1916 (BRACERS 112964). On 9 December (BRACERS 112977), she explained: “I want you as comrade as well as lover.” On 9 April 1917 (BRACERS 19145), he reciprocated the sentiment for the first time. In a letter of 1 January 1918 (BRACERS 19260), BR was so upset with her that he could no longer call her “heart’s comrade”. After their relationship was patched up, he wrote on 16 February 1918 (BRACERS 19290): “I do really feel you now again my Heart’s Comrade.” The last time that BR expressed the sentiment in a letter to her was 26 August 1921 (BRACERS 19742).

Home Secretary / Sir George Cave

Sir George Cave (1856–1928; Viscount Cave, 1918), Conservative politician and lawyer, was promoted to Home Secretary (from the Solicitor-General’s office) on the formation of the Lloyd George Coalition in December 1916. His political and legal career peaked in the 1920s as Lord Chancellor in the Conservative administrations led by Andrew Bonar Law and Stanley Baldwin. At the Home Office Cave proved to be something of a scourge of anti-war dissent, being the chief promoter, for example, of the highly contentious Defence of the Realm Regulation 27C (see Letter 51).

Miles Malleson

Miles Malleson (1888–1969), actor and playwright, was born in Croydon, Surrey, the son of Edmund and Myrrha Malleson. He married his first wife, a fellow actor, Lady Constance Annesley (stage name, Colette O’Niel), in 1915. They had met at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts). Their marriage was an “open” one. In 1914 Miles enlisted in the City of London Fusiliers and was sent to Malta. He became ill and was discharged, unfit for further service. He became active in the No-Conscription Fellowship and wrote anti-war stage plays as well as a pamphlet, Cranks and Commonsense (1916). In the 1930s he began to write for the screen and act in films, in which he became a very well-known character actor, as well as continuing his stage career at the Old Vic in London. He married three times: his second marriage was to Joan Billson, a physician (married 1923, divorced 1940), with whom he had two children; his third wife was Tatiana Lieven, an actress (married 1946). He died in London in March 1969.

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

Philip Morrell

Philip Morrell, Ottoline’s husband (1870–1943), whom she had married in 1902 and with whom, four years later, she had twins — Julian, and her brother, Hugh, who died in infancy. The Morrells were wealthy Oxfordshire brewers, although Philip’s father was a solicitor. He won the Oxfordshire seat of Henley for the Liberal Party in 1906 but held this Conservative stronghold only until the next general election, four years later. For the second general election of 1910 he ran successfully for the Liberals in the Lancashire manufacturing town of Burnley. But Morrell’s unpopular anti-war views later cost him the backing of the local Liberal Association, and his failure to regain the party’s nomination for the post-war election of 1918 (see Letter 89) effectively ended his short political career. Unlike many other Liberal critics of British war policy (including BR), Morrell did not transfer his political allegiance to the Labour Party. Although Ottoline and her husband generally tolerated each other’s extra-marital affairs, a family crisis ensued when in 1917 Philip impregnated both his wife’s maid and his secretary (see Letter 48).

Raphael Demos

Raphael Demos (1892–1968), one of BR’s logic students in the autumn of 1916. Then on a Sheldon travelling fellowship, Demos eventually returned to Harvard where he taught philosophy for the rest of his career. Russell had taught him at Harvard in 1914 and described him in his Autobiography (1: 212). In 1916–17 BR recommended two of his articles to G.F. Stout, the editor of Mind (“A Discussion of a Certain Type of Negative Proposition”, Mind 26 [Jan. 1917]: 188–96; and “A Discussion of Modal Propositions and Propositions of Practice”, 27 [Jan. 1918]: 77–85); see BRACERS 54831 and 2962 (and for Demos’s letters to BR in 1917 about the submissions, BRACERS 76495 and 76496, and BR’s reply to the first, BRACERS 838).

Russell Chambers

34 Russell Chambers, Bury Street (since renamed Bury Place), London WC1, BR’s flat since 1911. Helen Dudley rented the flat in late 1916 or early 1917. In May 1918 she sublet it to Clare Annesley. Colette moved in on 9 September 1918 and stayed until June 1919. BR did not give up the lease until December 1923. See S. Turcon, “Russell Chambers, Other London Flats, and Country Homes, 1911–1923”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 150 (Fall 2014): 30–4. “Russell Chambers, Other London Flats, and Country Homes, 1911–1923”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 150 (Fall 2014): 30–4.

The Attic

The Attic was the nickname of the flat at 6 Mecklenburgh Square, London WC1, rented by Colette and her husband, Miles Malleson. The house which contained this flat is no longer standing. “The spacious and elegant facades of Mecklenburgh Square began to be demolished in 1950. The houses on the north side were banged into dust in 1958. The New Attic was entirely demolished” (“Letters to Bertrand Russell from Constance Malleson, 1916–1969”, p. 109; typescript in RA).

The Studio

The accommodation BR and Colette rented on the ground floor at 5 Fitzroy Street, just off Howland Street, London W1. “It had a top light, a gas fire and ring. A water tap and lavatory in the outside passage were shared with a cobbler whose workshop adjoined” (Colette’s annotation at BRACERS 113087). It was ready to occupy in November 1917.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.