Brixton Letter 51

BR to Frank Russell

July 29, 1918

- ALS

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-51

BRACERS 46930

<Brixton Prison>1

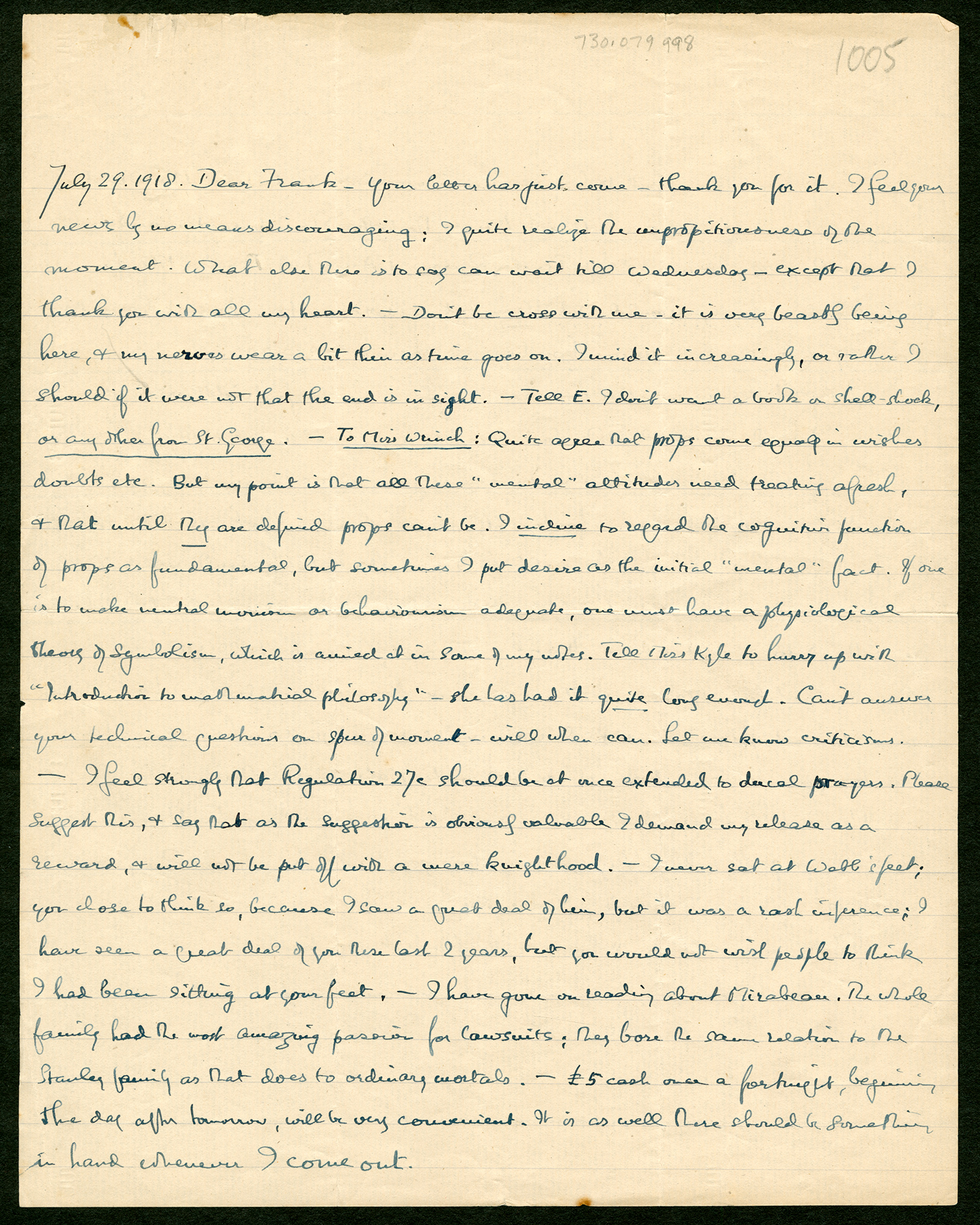

July 29. 1918.

Dear Frank

Your letter has just come2 — thank you for it. I feel your news by no means discouraging;3 I quite realize the unpropitiousness of the moment. What else there is to say can wait till Wednesday — except that I thank you with all my heart. — Don’t be cross with me — it is very beastly being here, and my nerves wear a bit thin as time goes on. I mind it increasingly, or rather I should if it were not that the end is in sight. — Tell E. I don’t want a book on shell-shock, or any other from St. George.4 — To Miss Wrinch: Quite agree that props come equally in wishes doubts etc. But my point is that all these “mental” attitudes need treating afresh, and that until they are defined props can’t be. I incline to regard the cognitive function of props as fundamental, but sometimes I put desire as the initial “mental” fact. If one is to make neutral monism or behaviourism adequate, one must have a physiological theory of symbolism,5 which is aimed at in some of my notes.6 Tell Miss Kyle to hurry up with Introduction to mathematical philosophy — she has had it quite long enough. Can’t answer your technical questions7 on spur of moment — will when can. Let me know criticisms.8 — I feel strongly that Regulation 27c should be at once extended to ducal prayers.9 Please suggest this, and say that as the suggestion is obviously valuable I demand my release as a reward, and will not be put off with a mere knighthood. — I never sat at Webb’s feet;10 you chose to think so, because I saw a great deal of him, but it was a rash inference; I have seen a great deal of you these last 2 years, but you would not wish people to think I had been sitting at your feet. — I have gone on reading about Mirabeau. The whole family had the most amazing passion for lawsuits; they bore the same relation to the Stanley family as that does to ordinary mortals.11 — £5 cash once a fortnight, beginning the day after tomorrow, will be very convenient. It is as well there should be something in hand whenever I come out.

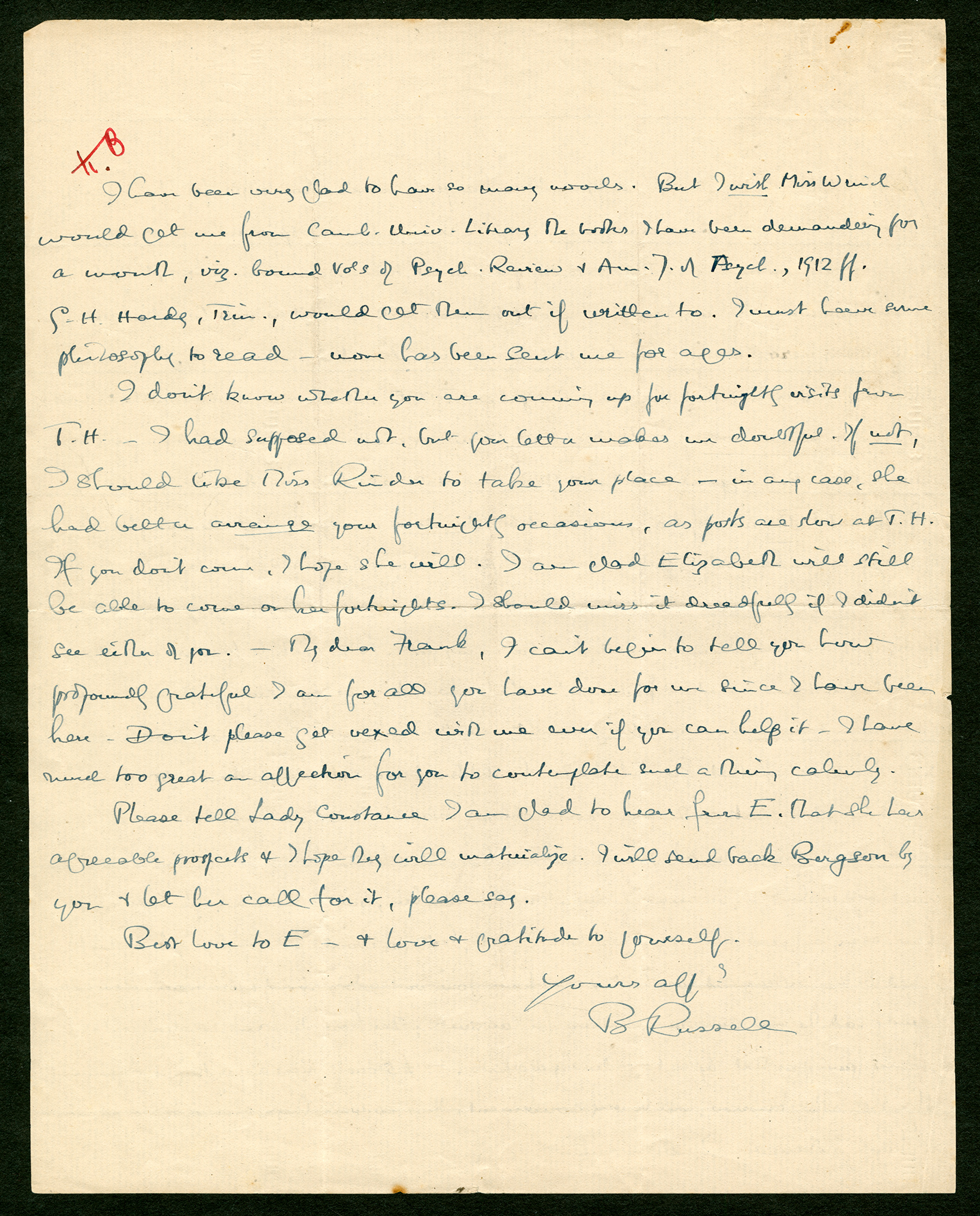

I have been very glad to have so many novels. But I wish Miss Wrinch would get me from Camb. Univ. Library the books I have been demanding for a month, viz. bound Vols of Psych. Review and Am. J. of Psych., 1912 ff.12 G.H. Hardy, Trin.,13 would get them out if written to. I must have some philosophy to read — none has been sent me for ages.

I don’t know whether you are coming up for fortnightly visits from T.H. — I had supposed not, but your letter makes me doubtful. If not, I should like Miss Rinder to take your place — in any case, she had better arrange your fortnightly occasions, as posts are slow at T.H. If you don’t come, I hope she will. I am glad Elizabeth will still be able to come on her fortnights.14 I should miss it dreadfully if I didn’t see either of you. — My dear Frank, I can’t begin to tell you how profoundly grateful I am for all you have done for me since I have been here. Don’t please get vexed with me ever if you can help it — I have much too great an affection for you to contemplate such a thing calmly.

Please tell Lady Constance I am glad to hear from E. that she has agreeable prospects15 and I hope they will materialize. I will send back Bergson by you16 and let her call for it, please say.

Best love to E — and love and gratitude to yourself.

Yours affly.

B Russell

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the signed, handwritten original in Frank Russell’s files in the Russell Archives. On thin, laid paper, it was folded three times and was approved by the Brixton governor’s deputy, whose initials “HB” are on the verso.

- 2

Your letter has just come Dated 23–26 July 1918 (BRACERS 46929).

- 3

your news by no means discouraging After meeting the Home Secretary on 26 July, Frank added this note to his letter: “Saw <Sir George> Cave this afternoon — am authorised to say you shall have 6 weeks remission for work: the rest he will ‘think about’” (BRACERS 46929). BR did get the six weeks’ remission, in addition to good behaviour, “for work” — which must be most unusual for a philosopher.

- 4

I don’t want a book on shell-shock, or any other from St. George The book was Grafton Eliot Smith and T.H. Pear, Shell Shock and Its Lessons (Manchester U. P., 1917). In part of the incoming letter from Frank, Elizabeth Russell informed her brother-in-law on 25 July that St. George Fox-Pitt (1856–1932) had sent her both this work and some Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research, thinking that BR, his cousin, “might like to see them” (see BRACERS 46929). Although disdaining the recommendations of somebody he regarded as a crank, BR was later intrigued by the Freudian approach to shell-shock of British psychologist and anthropologist W.H.R. Rivers (see “Instinct and the Unconscious”, 77 in Papers 15).

- 5

props come equally in wishes doubts etc. … desire as the initial “mental” fact … physiological theory of symbolism Here “equally” means “as well as in belief, knowledge, and understanding etc.” These states are all now known to philosophers as “propositional attitudes” (terminology that BR introduced around this time [Papers 8: 200, 268–9]). Interestingly, BR indicated that he “sometimes” treated desire as “the initial, ‘mental’ fact”, even though his inclination was to take the cognitive propositional attitudes (paradigmatically, belief, knowledge, and understanding) as such. However, in The Analysis of Mind (1921), in which all this work culminated, he treated desire behaviouristically and not as a propositional attitude at all. Wrinch’s approach (which would have been BR’s before 1910) was that one should start with propositions and then, as it were, build on the psychological component. BR’s current approach was that one must do the psychological work first, because propositions themselves are psychological entities, composed of words or (more fundamentally) images which represent the objects which make up the putative state of affairs that the proposition expresses. Indeed, as he went on to say, if neutral monism or behaviourism is to work, we need a “physiological theory of symbolism”, which would relate propositions to facts without any neutral intermediary. The closest BR ever got to one is in Appendix C of the second edition of Principia Mathematica.

- 6

aimed at in some of my notes E.g., “Three Subjects” (the subjects being facts, judgments and propositions) and “Propositions” discuss BR’s theory of symbolism (18g and 18h in Papers 8).

- 7

your technical questions The technical questions were posed by Wrinch in her message contained in Frank Russell’s letter of 23–26 July 1918 (BRACERS 46929): “Very many points are coming up with regard to your work on Facts, Judgments, and Propositions, which I want to put out for you if you feel inclined. One might want, I think, something beyond facts and propositions — if propositions are to be defined as symbols for judgments, as propositions as sometimes used occur in wishes, hopes, commands, fears, decisions, doubts, denials, supposings, suggestings, knowings … and from many other acts; and the occurrence of propositions in judgments does not appear any more fundamental than occurrences in other acts. The difficulty I want to put to you is this: if a proposition is always merely the symbol of a judgment — and if such a thing always has a subject term and some relation peculiar to judging, then what becomes of the similarity between one term (if propositions are genuine constituents) of a judgment and one term of a hope, a doubt, a supposing …, or between constructed terms, (if propositions are not genuine constituents)? If it, on the other hand, does not have a relation peculiar to judging in it, how can it be derived from judgings, rather than from any other kind of act? Can one not have another kind of thing neutral between judgings … and hopes, desires, etc. For then judgments will be correct (say) when propositions are true, hopes … fulfilled … and so on. Then if ϕp is an act of judging or hoping, etc. a certain fact such as ‘p is true’ will entail χ(ϕp) where χ will vary with ϕ. Thus if ϕ is judging, χ will be correct, or if ϕ is hoping, χ might be is realised. This might also make it plausible to explain the fact that <gap> judge it will rain, and hope it may rain, and doubt whether it will rain, are of slightly different form, by the difference in the ϕ. But all this is only to suggest that it might be satisfactory to make the proposition common to judgings, fearings, etc. instead of derivative from judgment alone. And, would not all stuff about differences of correspondence between judgments and facts apply equally to those between hopes, fears, … and facts … and does this not point to the desirability of introducing something common to all these acts? Whether the propositions as you used to use the term is an entity or a logical construction, is not it that which you are discussing and not something having a relation to judgments which it does not have to other acts? I put these suggestions very tentatively. I am finding the MSS most interesting and stimulating. I would like to write more to you about them.”

- 8

criticisms BR sent his answers to Wrinch’s technical questions on 31 July in a short manuscript called “Propositions” (18h in Papers 8). Wrinch sent criticisms as part of a long philosophical letter dated August 1918 (BRACERS 81966). It was probably in response to that that BR told Ottoline Morrell on 14 August (Letter 70) that Wrinch did not understand “the new ideas that I am at. It is no wonder, as my ideas are still rather vague.… I can’t get expression for them yet.”

- 9

Regulation 27c should be ... extended to ducal prayers BR was humorously urging the suppression of further prayers for rain by the Duke of Rutland (see Letter 41). Not to be confused with Defence of the Realm Regulation 27 (under which BR had twice been prosecuted and convicted), 27C imposed an even more contentious constraint over freedom of expression. Pertaining exclusively to the printing and distribution of leaflets, Regulation 27C, as initially implemented by Order in Council on 16 November 1917, stipulated that all such material be sent to and passed by the Official Press Bureau. Publishers of the anti-war literature against which this preventive censorship was squarely directed joined a chorus of civil libertarian protest, which resulted barely a month later in the prior-approval provision being dropped. But since the printers of leaflets were still required to submit copy in advance of publication, the authorities were better able than previously to monitor the output of pacifist literature and already equipped with other emergency powers under “DORA” to suppress allegedly objectionable material. Gladys Rinder’s mention early in July 1918 (BRACERS 79617) of unwanted “visitors” at 5 York Buildings, London, the publishing office of The Tribunal, hints at the vulnerability of the No-Conscription Fellowship to such measures.

- 10

I never sat at Webb’s feet In a 1955 radio broadcast, however, BR did admit to having briefly fallen “under the influence” of Webb (1859–1947) and his wife Beatrice, Fabian theorists, historians and social investigators (see Papers 28: 131). In 1902 BR joined the Coefficients, a small discussion group founded by the Webbs and dedicated to the new vogue for “national efficiency”. But BR found the atmosphere thick with imperialist and protectionist sentiment and left within a year. For the influence of the Webbs’ on BR’s “wrong” support of the Boer War, see Royden Harrison, “Bertrand Russell and the Webbs: an Interview”, Russell 5 (1985): 44–9.

- 11

Mirabeau. The whole family … passion for lawsuits … Stanley family … ordinary mortals As a young man, the future French revolutionary leader Honoré-Gabriel Riqueti, Comte de Mirabeau (1749–1791) — whose memoirs BR was reading — became embroiled in an acrimonious legal dispute with his father. The Marquis de Mirabeau even obtained a lettre de cachet against his scandal-prone son, under which the Comte was forcibly confined for over three years in Vincennes castle. After he was released in 1780, Mirabeau’s wife petitioned for a judicial separation from her estranged (and adulterous) husband. Almost two decades previously Mirabeau senior had judicially separated from his wife, but for years the couple continued to wrangle in the courts over her allowance. BR was implying that his mother’s large aristocratic family, the Stanleys of Alderley, had a similar, if not nearly so pronounced, litigious “passion”. No compelling evidence for this comparison has been found, aside from a protracted (and ultimately unsuccessful) patent-infringement suit launched in the 1890s by electrical inventor St. George Lane Fox-Pitt (1856–1932) — the son of BR’s “Stanley” Aunt Alice (see Stathis Arapostathis and Graeme Gooday, Patently Contestable: Electrical Technologies and Inventor Identities on Trial in Britain [Cambridge, Mass.: MIT P., 2013], Chap. 5). It cannot be said that the Russell family itself was shy of going to the law, Frank very much included (as BR experienced over his rental of Telegraph House in 1927). Over his lifetime BR himself had an unusually large experience of the law, some of it initiated by himself.

- 12

I have been demanding … Psych. Review and Am. J. of Psych., 1912 ff. However belatedly, BR’s request to Dorothy Wrinch was eventually fulfilled — although possibly, as hinted here, by G.H. Hardy instead. In prison he read 23 articles from volumes 18–23 (1911–16) of The Psychological Review, and another seven from volumes 21 and 23 (1910 and 1912) of The American Journal of Psychology. (See the list of his philosophical prison reading in Papers 8: App. III.) He had already, by 21 May 1918, received, courtesy of H. Wildon Carr, a single volume of the former periodical (see Letter 7).

- 13

G.H. Hardy, Trin. Godfrey Harold Hardy (1877–1947) was a pure mathematician who specialized in number theory and analysis and collaborated productively with another of BR’s Trinity College friends, J.E. Littlewood. In the course of a distinguished career, Hardy held professorships at both Oxford and Cambridge. In January 1917 he led 21 other Trinity fellows in protesting BR’s dismissal by the College Council, and after the war led a successful campaign for his reinstatement, later authoring Bertrand Russell and Trinity (printed for the author by Cambridge U. P., 1942; reprinted with a foreword by C.D. Broad, 1970).

- 14

your fortnightly occasions … her fortnights BR means the prison visits from his friends. Evidently Frank visited every two weeks during this period.

- 15

Lady Constance … agreeable prospects In her part of Frank Russell’s letter of 23–26 July, Elizabeth noted that Colette had the prospect of a three-year engagement in London. No further details are known, and the unlikely long engagement for a struggling actress (or any actress, for that matter) did not come off. This could be an oblique reference to the Experimental Theatre. In her letter to BR of 28 July (BRACERS 113146), Colette mentioned that “E. subscribed generously” to it.

- 16

I will send back Bergson by you The book by French philosopher Henri Bergson (1859–1941) cannot be identified; it was being used to smuggle correspondence to and from Colette (see Letter 52).

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

C.D. Broad

Charlie Dunbar Broad (1887–1971), British philosopher, studied at Trinity College, Cambridge (1906–10), where he came in contact with BR, whose work had the greatest influence on him, though he was taught primarily by W.E. Johnson and J.M.E. McTaggart. (He wrote the definitive refutation of McTaggart’s philosophy after the latter’s death.) In 1911 BR examined Broad’s fellowship dissertation, which was published as Perception, Physics, and Reality (1914) and which BR reviewed in Mind in 1918 (15 in Papers 8). BR reviewed more books by Broad in the 1920s, and Broad returned the favour over the decades. Outstanding among his reviews was that of the first volume of BR’s Autobiography in The Philosophical Review 77 (1968): 455–73. From 1911 to 1920 Broad taught at St. Andrews University; in 1920 he moved to Bristol as Professor of Philosophy before returning to Trinity in 1923, where, as Knightbridge Professor of Moral Philosophy, he remained for the rest of his life. He wrote extensively on a wide range of philosophical topics, including ethics, philosophy of mind, philosophy of science, and psychical research. His philosophical writings are marked by the impartiality and clarity with which he stated, revised, and assessed the arguments and theories with which he was dealing, rather than by originality in his own position. BR and Moore were the two philosophers with whose views his were most closely aligned. Broad was evidently devoted to BR. One of the current editors was introduced to Broad upon visiting Trinity College Library in 1966. He was keen to hear about BR from someone who had recently talked with him. Following BR’s death Broad introduced a reprint of G.H. Hardy’s Bertrand Russell and Trinity: a College Controversy of the Last War (Cambridge U. P., 1944; 1970).

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.

Dorothy Wrinch

Dorothy Maud Wrinch (1894–1976), mathematician, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. She studied mathematics and philosophy at Girton College, Cambridge, and came under BR’s influence in her second year when she took his course on mathematical logic. She taught mathematics at University College, London, 1918–21, and then at Oxford, 1922–30. Her first publications were in mathematical logic and philosophy, and during the 1920s she wrote on the philosophy of science. But in the 1930s her interests turned to mathematical biology and crystallography, and in 1935 she moved to the United States on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship and remained there for the rest of her life. Unfortunately, as a biologist she is best known for a long and stubborn controversy with Linus Pauling about the structure of proteins in which he was right and she was wrong. See Marjorie Senechal, I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science (New York: Oxford U. P., 2013). Chapter 7 is devoted to Wrinch’s interactions with BR in Brixton.

Elizabeth Russell

Elizabeth Russell, born Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941), was a novelist who in 1891 married Graf von Arnim-Schlagenthin. She became known as “Elizabeth”, the name she used in publishing Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898), and she remained widely known as Elizabeth von Arnim, although the Library of Congress catalogues her as Mary Annette (Beauchamp), Countess von Arnim. She was a widow when she married BR’s brother, Frank, on 11 February 1916. The marriage was quickly in difficulty; she left it for good in March 1919, but they were never divorced and she remained Countess Russell (becoming Dowager Countess after Frank’s death in 1931).

Eva Kyle

Eva Kyle ran a typing service. She did work for the No-Conscription Fellowship and took BR’s dictation of his book, Roads to Freedom, in the early months of 1918. He annotated a letter from her: “She was an admirable typist but very fat. We all agreed that she was worth her weight in gold, though that was saying a great deal.” Her prison letter to him is clever and amusing. She typed his major prison writings and apologized for the amount of the invoice when he emerged.

Experimental Theatre

Colette first mentioned that she and Miles were trying to start an Experimental Theatre in a letter of 24 June 1918 (BRACERS 113135), indicating that Miles would earn a tiny income from it. About a month later, she wrote that Elizabeth Russell had subscribed generously to the Theatre and that £700 had been raised, but hundreds still had to be found (BRACERS 113146). A few days later she wrote that Captain Stephen Gordon, a north-country lawyer working for the government, was to be the honorary treasurer, noting that he had “put most of the drive into the whole thing” (BRACERS 113147). During August Colette was happy with her involvement with the Theatre (Letter 68). John Galsworthy came to tea to discuss the project (c.14 Aug., BRACERS 113149). On 2 September she listed the members of the Theatre committee as “Desmond <MacCarthy>, Massingham, Galsworthy, and Dennis (Bradley)” (BRACERS 113155). The following day she wrote that she was learning three parts (BRACERS 113156). In her memoirs, Colette wrote about the “Experimental Little Theatre” but dated it 1919 (After Ten Years [London: Cape, 1931], pp. 129–30). An “artistic” theatre did get founded in 1920 in Hampstead, and John Galsworthy was connected to that venture, The Everyman Theatre — he was part of a reading committee which chose the works to be performed (The Times, 9 Sept. 1919, p. 8). The Everyman Theatre was under the direction of Norman MacDermott. In his book Everymania (London: Society for Theatre Research, 1975), he noted that he met Miles in the summer of 1918: they rented a store in Bloomsbury, had a cabinetmaker build sets, and put on plays with actors “bored with West-End theatres” (p. 10). It is likely that the Everyman Theatre was an out-growth of the Experimental Theatre.

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Governor of Brixton Prison / Carleton Haynes

Captain Carleton Haynes (1858–1945), the Governor of Brixton Prison in 1918, was a retired army officer and a cousin of BR’s acquaintance, the radical lawyer and author E.S.P. Haynes. In March 1919 BR sent Haynes, in jest, a copy (now in the Russell Archives) of his newly published Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy — so that the governor’s collection of works written by inmates while under his charge would “not ... be incomplete” (BRACERS 123167).

H. Wildon Carr

Herbert Wildon Carr (1857–1931), Professor of Philosophy at King’s College, London, from 1918 and Visiting Professor at the University of Southern California from 1925. Carr came to philosophy late in life after a lucrative career as a stockbroker. His philosophy was an idiosyncratic amalgam of Bergsonian vitalism and Leibnizian monadology, which, he thought, was supported by modern biology and the theory of relativity. He wrote books on Bergson and Leibniz at opposite ends of his philosophical career and a book on relativity in the middle. His philosophy would have made him an unlikely ally of BR’s, but it was Carr who organized BR’s two courses of public lectures, on philosophy of mathematics and the philosophy of logical atomism, which brought BR back to philosophy and improved his finances in 1917–18. Carr had great administrative talents, which he employed also on behalf of the Aristotelian Society during his long association with it. He was its president in 1916–18 and continued to edit its Proceedings until 1929.

Home Secretary / Sir George Cave

Sir George Cave (1856–1928; Viscount Cave, 1918), Conservative politician and lawyer, was promoted to Home Secretary (from the Solicitor-General’s office) on the formation of the Lloyd George Coalition in December 1916. His political and legal career peaked in the 1920s as Lord Chancellor in the Conservative administrations led by Andrew Bonar Law and Stanley Baldwin. At the Home Office Cave proved to be something of a scourge of anti-war dissent, being the chief promoter, for example, of the highly contentious Defence of the Realm Regulation 27C (see Letter 51).

J.E. Littlewood

John Edensor Littlewood (1885–1977), mathematician. In 1908 he became a fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, and remained one for the rest of his life. In 1910 he succeeded Whitehead as college lecturer in mathematics and began his extraordinarily fruitful, 35-year collaboration with G.H. Hardy. During the First World War he worked on ballistics for the British Army. He and BR were to share Newlands farm, near Lulworth, during the summer of 1919. Littlewood had two children, Philip and Ann Streatfeild, with the wife of Dr. Raymond Streatfeild.

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

Principia Mathematica

Principia Mathematica, the monumental, three-volume work coauthored with Alfred North Whitehead and published in 1910–13, was the culmination of BR’s work on the foundations of mathematics. Conceived around 1901 as a replacement for the projected second volumes of BR’s Principles of Mathematics (1903) and of Whitehead’s Universal Algebra (1898), PM was intended to show how classical mathematics could be derived from purely logical principles. For a large swath of arithmetic this was done by actually producing the derivations. A fourth volume on geometry, to be written by Whitehead alone, was never finished. In 1925–27 BR, on his own, produced a second edition, adding a long introduction, three appendices and a list of definitions to the first volume and corrections to all three. (See B. Linsky, The Evolution of Principia Mathematica [Cambridge U. P., 2011].) In this edition, under the influence of Wittgenstein, he attempted to extensionalize the underlying intensional logic of the first edition.

Telegraph House

Telegraph House, the country home of BR’s brother, Frank. It is located on the South Downs near Petersfield, Hants., and North Marden, W. Sussex. See S. Turcon, “Telegraph House”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 154 (Fall 2016): 45–69.

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).