Brixton Letter 50

BR to Constance Malleson

July 27, 1918

- AL

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-50

SLBR 2: #316

BRACERS 19321

<Brixton Prison>1

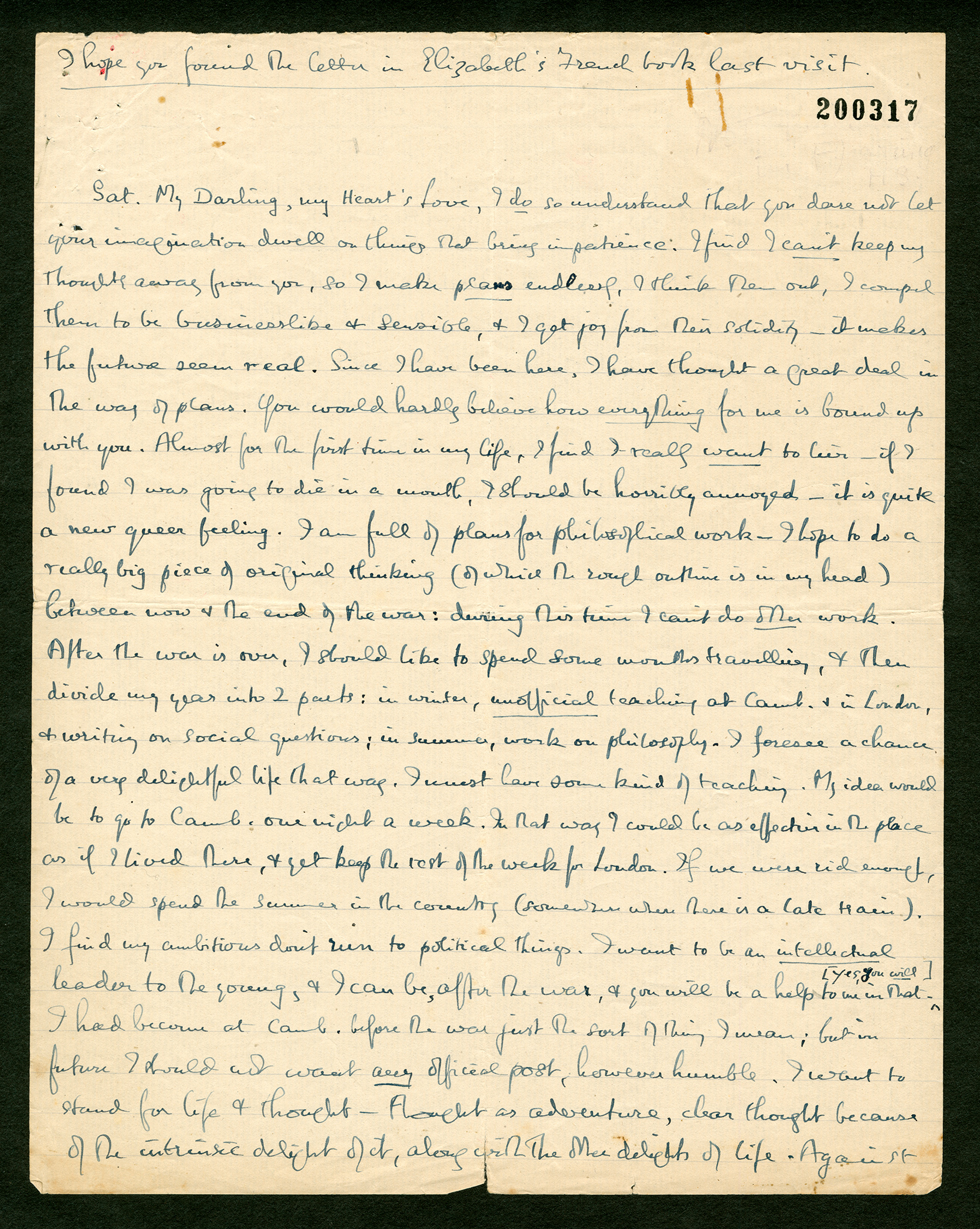

Sat.2

My Darling, my Heart’s Love,

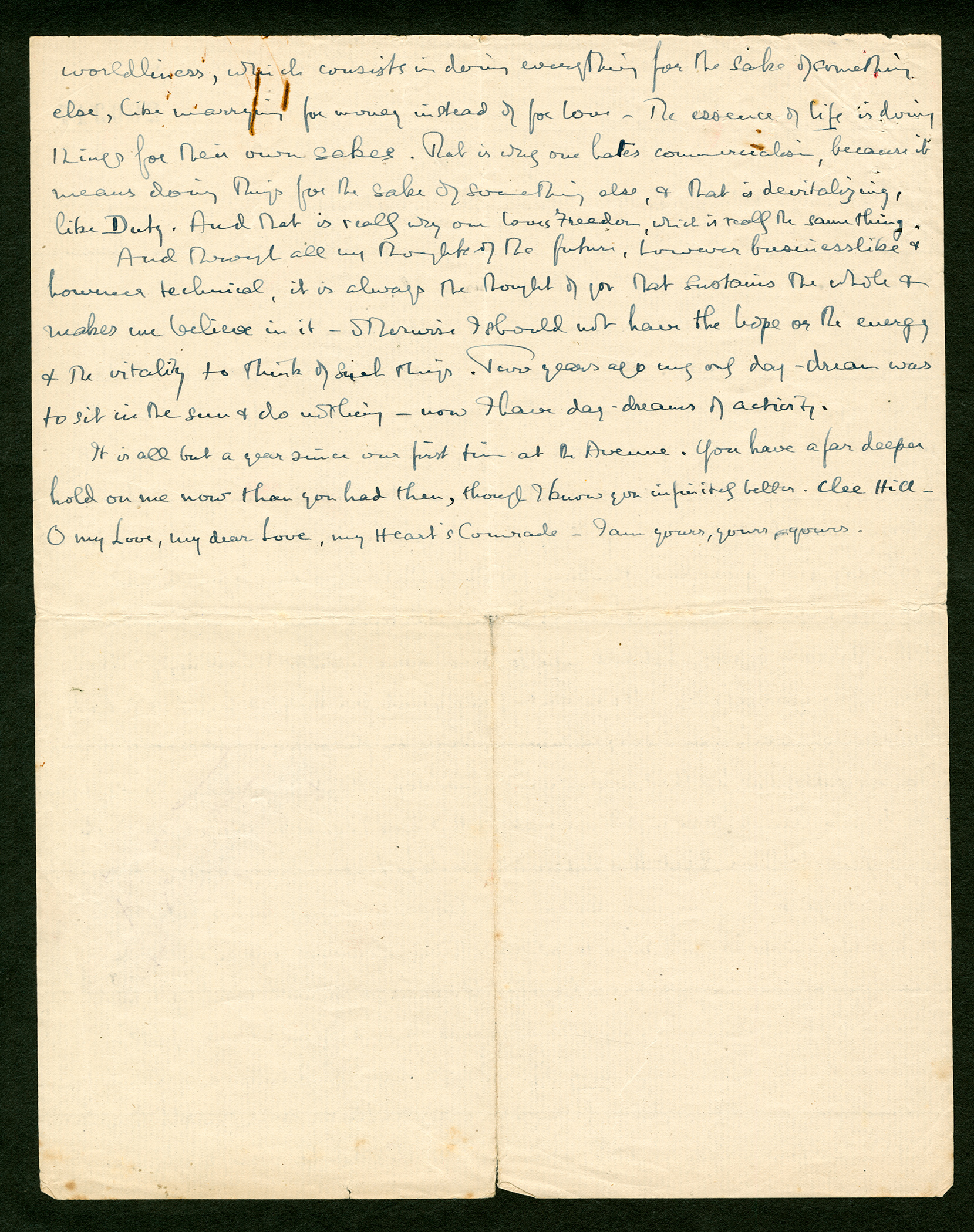

I do so understand that you dare not let your imagination dwell on things that bring impatience. I find I can’t keep my thoughts away from you, so I make plans endlessly, I think them out, I compel them to be businesslike and sensible, and I get joy from their solidity — it makes the future seem real. Since I have been here, I have thought a great deal in the way of plans. You would hardly believe how everything for me is bound up with you. Almost for the first time in my life, I find I really want to live — if I found I was going to die in a month, I should be horribly annoyed — it is quite a new queer feeling. I am full of plans for philosophical work.3 I hope to do a really big piece of original thinking (of which the rough outline is in my head) between now and the end of the war: during this time I can’t do other work. After the war is over, I should like to spend some months travelling, and then divide my year into 2 parts: in winter, unofficial teaching at Camb. and in London,4 and writing on social questions; in summer, work on philosophy. I foresee a chance of a very delightful life that way. I must have some kind of teaching. My idea would be to go to Camb. one night a week. In that way I could be as effective in the place as if I lived there, and yet keep the rest of the week for London. If we were rich enough, I would spend the summer in the country (somewhere where there is a late train). I find my ambitions don’t run to political things. I want to be an intellectual leader to the young, and I can be, after the war, and you will be a help to me in that. [Yes, you will]a I had become at Camb. before the war just the sort of thing I mean; but in future I should not want any official post, however humble. I want to stand for life and thought — thought as adventure, clear thought because of the intrinsic delight of it, along with the other delights of life. Against worldliness, which consists in doing everything for the sake of something else, like marrying for money instead of for love. The essence of life is doing things for their own sakes.5 That is why one hates commercialism, because it means doing things for the sake of something else, and that is devitalizing, like Duty. And that is really why one loves Freedom, which is really the same thing.

And through all my thoughts of the future, however businesslike and however technical, it is always the thought of you that sustains the whole and makes me believe in it — otherwise I should not have the hope or the energy and the vitality to think of such things. Two years ago my only day-dream was to sit in the sun and do nothing — now I have day-dreams of activity.

It is all but a year since our first time at the Avenue.6 You have a far deeper hold on me now than you had then, though I know you infinitely better. Clee Hill — O my love, my dear love, my Heart’s Comrade. I am yours, yours, yours.

I hope you found the letter in Elizabeth’s French book last visit.b

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the unsigned, handwritten original in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. It was folded twice, exposing the two quarters that BR left blank on the verso of the sheet. The letter was published as #316 in Vol. 2 of BR’s Selected Letters.

- 2

[date]Colette suggested the dates of 20 or 27 July 1918 for the letter in a note (document 200316). Since the first time they visited the Avenue was 31 July 1917, the more likely date is 27 July, and BR did write that it had been “all but a year”.

- 3

full of plans for philosophical work By early June BR had finished his work on Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy and a long review of Dewey’s Essays in Experimental Logic and had spent the first part of July reading in psychology. The most detailed account of his plans (written 14 Aug. 1918; see Letter 69, note 4) is printed as Appendix II of Papers 8 (where, however, it is dated as having been written before he went into prison). The Analysis of Mind (1921), which actually resulted, was a smaller work.

- 4

unofficial teaching at Camb. and in London Since being deprived of his lectureship in logic and the principles of mathematics by Trinity College Council in July 1916, BR’s only realistic prospect of philosophical lecturing at Cambridge was on such ad hoc terms. He did not satisfy this ambition, but had already delivered two notable series of “unofficial” lectures in London(on philosophy of mathematics, from which his Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy emerged in prison, and “The Philosophy of Logical Atomism”). From May to June 1919 he presented a third series (“The Analysis of Mind”) at the same venue, Dr. Williams’ Library in Bloomsbury. Later in the year and in 1920 the series was doubled in length and given twice, at Dr. Williams’ Library and Morley College.

- 5

doing things for their own sakes That is, because we have an impulse to do them, and not because doing them is the means to something else. BR put the satisfaction of impulse very high in his philosophy of happiness in both Principles of Social Reconstruction (1916), Ch. 1, and The Conquest of Happiness (1930), especially Chapter 11 on zest.

- 6

our first time at the Avenue Their first night at the Avenue was probably 31 July 1917; they stayed until mid-August.

Textual Notes

Boismaison

Colette and BR vacationed at a house, The Avenue, owned by Mrs. Agnes Woodhouse and her husband, in the countryside near Ashford Carbonel, Shropshire, in August 1917. They nicknamed the house “Boismaison”. Agnes Woodhouse took in paying guests. Their first visit was idyllic. They returned for other vacations — in 1918 before he entered prison and in April 1919. Their plan to go soon after he got out of prison failed because their relationship faltered for a time. They discussed returning in the summer of 1919 — a booking was even made for 12–19 July — but in the end they didn’t go. See S. Turcon, “Then and Now: Bertie and Colette’s Escapes to the Peak District and Welsh Borderlands”, Russell 34 (2014): 117–30.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Clee Hill

Near Ashford Carbonel, Shropshire, where BR and Colette spent an idyllic summer holiday in August 1917, staying in house named “The Avenue”. BR mentioned the day at Clee Hill in several letters, the last on 8 September 1918 (Letter 100). What exactly happened on that day is not clear in any of his letters. However, in a prison message to BR, Colette remembered that a red fox came and listened to them there (Rinder to BR, 15 June 1918, BRACERS 79614). They also vacationed at The Avenue in March 1918, before BR entered prison.

Elizabeth Russell

Elizabeth Russell, born Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941), was a novelist who in 1891 married Graf von Arnim-Schlagenthin. She became known as “Elizabeth”, the name she used in publishing Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898), and she remained widely known as Elizabeth von Arnim, although the Library of Congress catalogues her as Mary Annette (Beauchamp), Countess von Arnim. She was a widow when she married BR’s brother, Frank, on 11 February 1916. The marriage was quickly in difficulty; she left it for good in March 1919, but they were never divorced and she remained Countess Russell (becoming Dowager Countess after Frank’s death in 1931).

Heart’s Comrade

Colette first called BR her “heart’s comrade” in her letter of 17 November 1916 (BRACERS 112964). On 9 December (BRACERS 112977), she explained: “I want you as comrade as well as lover.” On 9 April 1917 (BRACERS 19145), he reciprocated the sentiment for the first time. In a letter of 1 January 1918 (BRACERS 19260), BR was so upset with her that he could no longer call her “heart’s comrade”. After their relationship was patched up, he wrote on 16 February 1918 (BRACERS 19290): “I do really feel you now again my Heart’s Comrade.” The last time that BR expressed the sentiment in a letter to her was 26 August 1921 (BRACERS 19742).

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.