Brixton Letter 48

BR to Ottoline Morrell

July 25, 1918

- ALS

- Texas

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-48SLBR 2: #317

BRACERS 18682

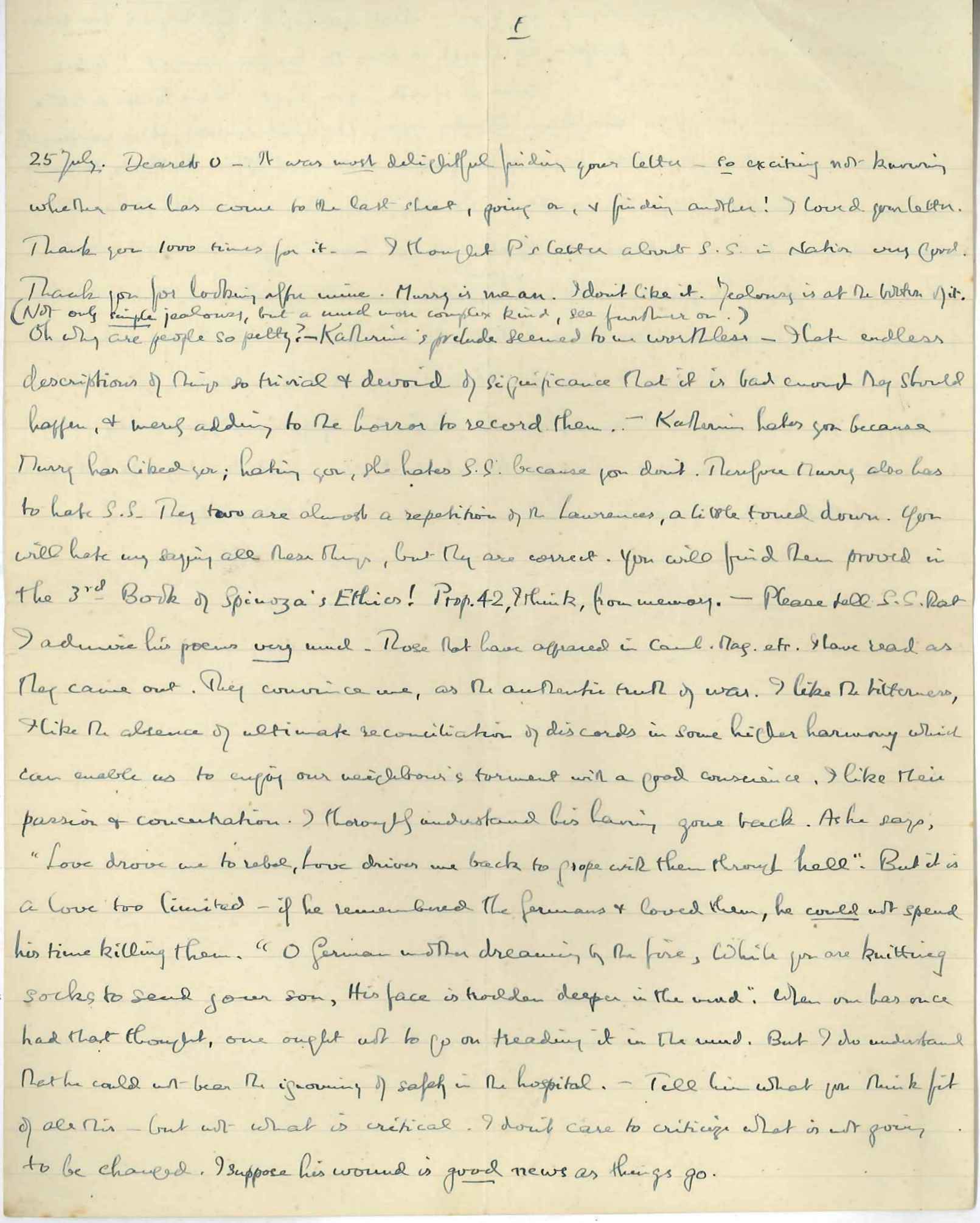

<Brixton Prison>1

25 July.

Dearest O

It was most delightful finding your letter2 — so exciting not knowing whether one has come to the last sheet, going on, and finding another! I loved your letter. Thank you 1000 times for it. — I thought P’s letter about S.S. in Nation very good. Thank you for looking after mine.3 Murry is mean. I don’t like it. Jealousy is at the bottom of it. (Not only simple jealousy, but a much more complex kind, see further on.)a Oh why are people so petty? — Katherine’s Preludeb seemed to me worthless4 — I hate endless descriptions of things so trivial and devoid of significance that it is bad enough they should happen, and merely adding to the horror to record them. — Katherine hates you because Murry has liked you; hating you, she hates S.S. because you don’t. Therefore Murry also has to hate S.S.5 They two are almost a repetition of the Lawrences, a little toned down.6 You will hate my saying all these things, but they are correct. You will find them proved in the 3rd Book of Spinoza’s Ethics! Prop. 42,7 I think, from memory. — Please tell S.S. that I admire his poems very much. Those that have appeared in Camb. Mag.8 etc. I have read as they came out. They convince me, as the authentic truth of war. I like the bitterness, I like the absence of ultimate reconciliation of discords in some higher harmony9 which can enable us to enjoy our neighbour’s torment with a good conscience. I like their passion and concentration. I thoroughly understand his having gone back.10 As he says, “Love drove me to rebel, Love drives me back to grope with them through hell”.11 But it is a love too limited — if he remembered the Germans and loved them, he could not spend his time killing them. “O German mother dreaming by the fire, While you are knitting socks to send your son, His face is trodden deeper in the mud”.12 When one has once had that thought, one ought not to go on treading it in the mud. But I do understand that he could not bear the ignominy of safety in the hospital. — Tell him what you think fit of all this — but not what is critical. I don’t care to criticize what is not going to be changed. I suppose his wound is good news as things go.13

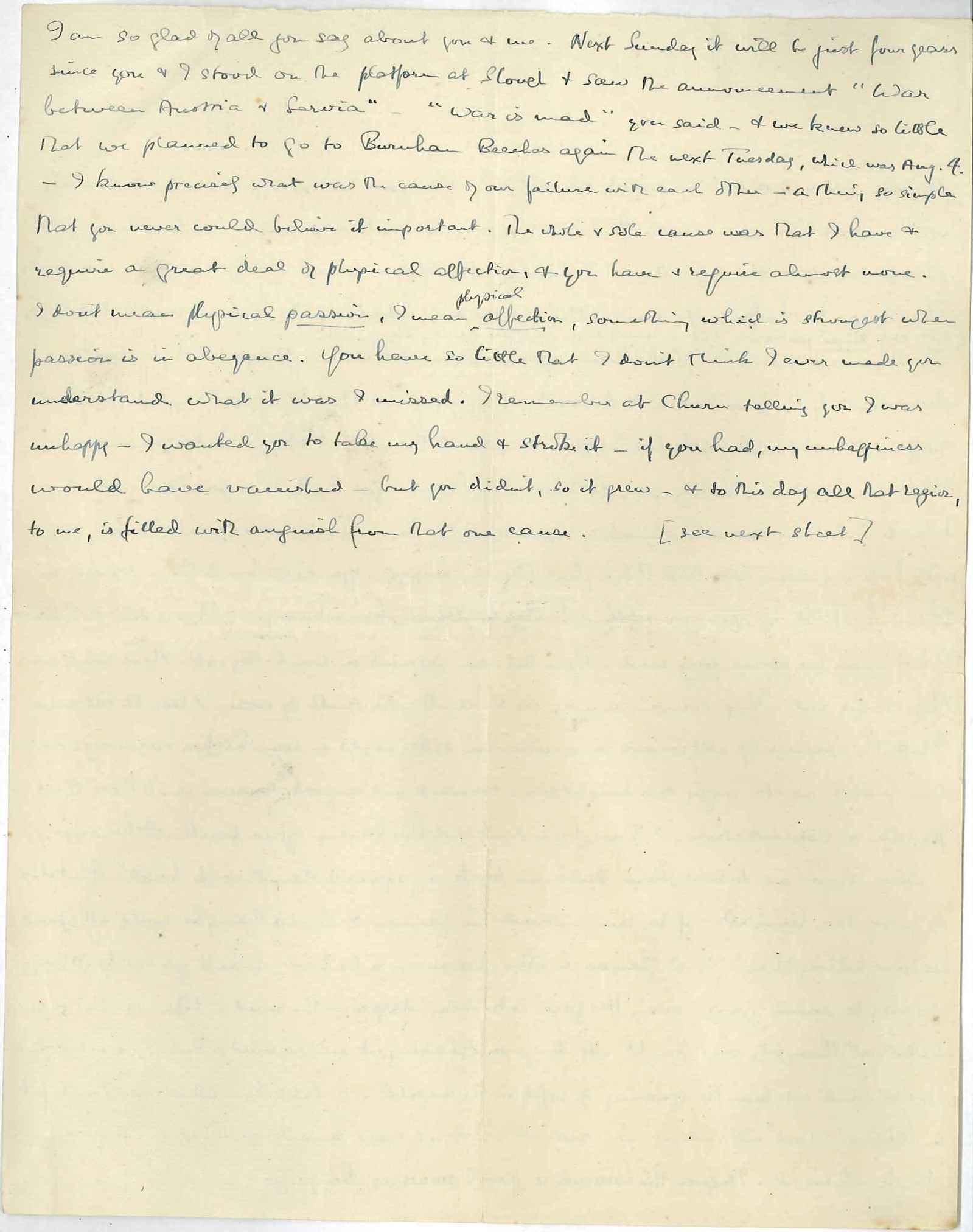

I am so glad of all you say about you and me.14 Next Sunday it will be just four years since you and I stood on the platform at Slough and saw the announcement “War between Austria and Servia” — “War is mad” you said — and we knew so little that we planned to go to Burnham Beeches again the next Tuesday, which was Aug. 4.15 — I know precisely what was the cause of our failure with each other — a thing so simple that you never could believe it important. The whole and sole cause was that I have and require a great deal of physical affection, and you have and require almost none. I don’t mean physical passion, I mean physicalc affection, something which is strongest when passion is in abeyance. You have so little that I don’t think I ever made you understand what it was I missed. I remember at Churn16 telling you I was unhappy. I wanted you to take my hand and stroke it — if you had, my unhappiness would have vanished — but you didn’t, so it grew — and to this day all that region, to me, is filled with anguish from that one cause. [see next sheet]

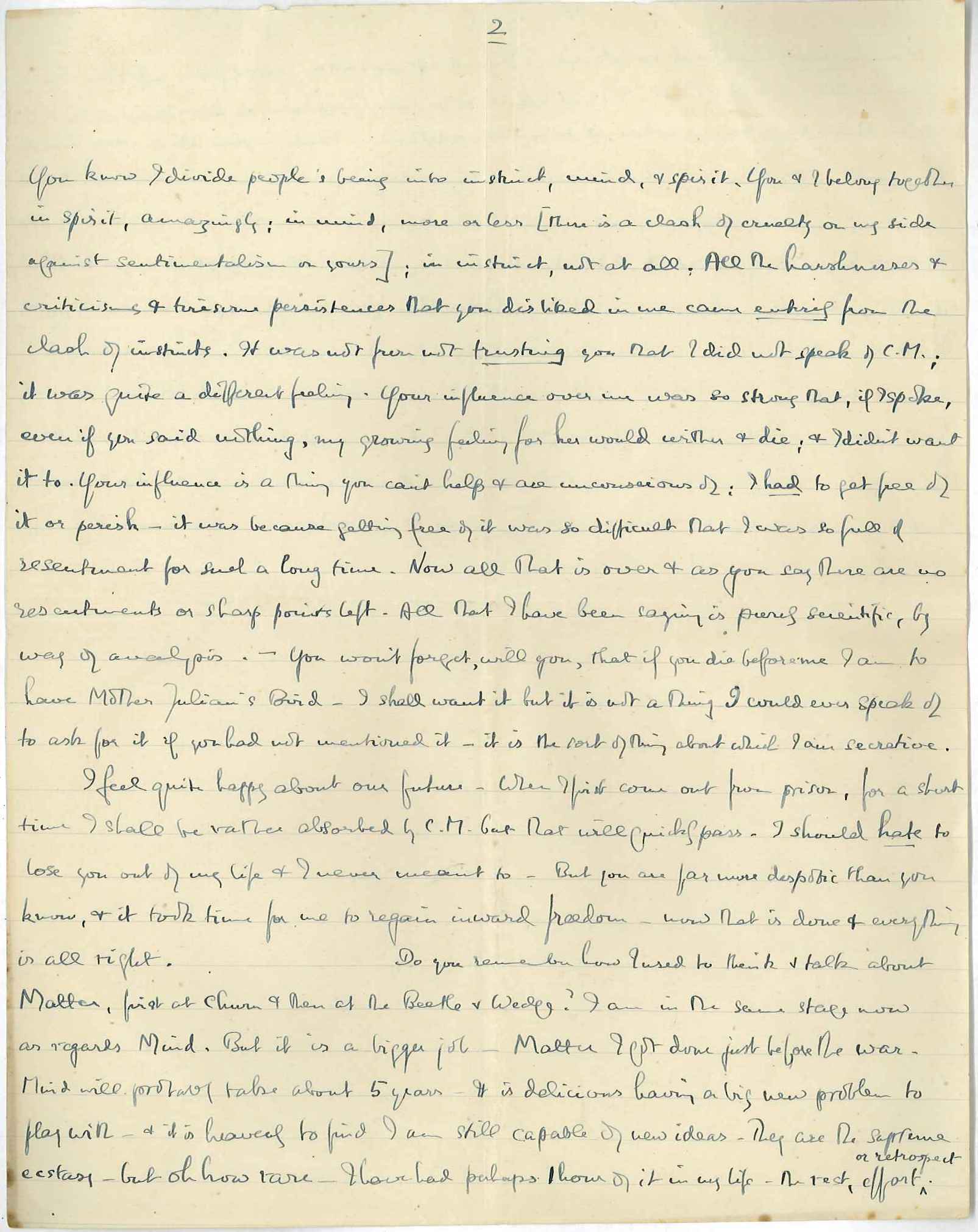

You know I divide people’s being into instinct, mind, and spirit.17 You and I belong together in spirit, amazingly; in mind, more or less [there is a clash of cruelty on my side against sentimentalism on yours]; in instinct, not at all. All the harshnesses and criticisms and tiresome persistences that you disliked in me came entirely from the clash of instincts. It was not from not trusting you that I did not speak of C.M.;18 it was quite a different feeling. Your influence over me was so strong that, if I spoke, even if you said nothing, my growing feeling for her would wither and die; and I didn’t want it to. Your influence is a thing you can’t help and are unconscious of; I had to get free of it or perish — it was because getting free of it was so difficult that I was so full of resentment for such a long time. Now all that is over and as you say there are no resentments or sharp points left. All that I have been saying is purely scientific, by way of analysis. — You won’t forget, will you, that if you die before me I am to have Mother Julian’s Bird.19 I shall want it but it is not a thing I could ever speak of to ask for it if you had not mentioned it — it is the sort of thing about which I am secretive.

I feel quite happy about our future. When I first come out from prison, for a short time I shall be rather absorbed by C.M. but that will quickly pass. I should hate to lose you out of my life and I never meant to. But you are far more despotic than you know, and it took time for me to regain inward freedom — now that is done and everything is all right.d

Do you remember how I used to think and talk about Matter, first at Churn and then at the Beetle and Wedge? I am in the same stage now as regards Mind. But it is a bigger job. Matter I got done just before the war.20 Mind will probably take about 5 years. It is delicious having a big new problem to play with — and it is heavenly to find I am still capable of new ideas. They are the supreme ecstasy — but oh how rare — I have had perhaps 1 hour of it in my life — the rest, effort or retrospect.e

I am intensely impatient to get out. I mind being taken away from affection and from intelligent talk — but I don’t want to be like Chappelow21 on his “dear ones” — and in these days one is ashamed to mind anything. But in fact it is very hard to work well here, and I have ideas I desperately want to work out. They did not tell me of the aspirin, but now I have spoken to the medical officer22 and he says I shall have it if I need it, but I don’t at the moment. It was good of you to send it. I expect when my head is worst it is better than yours ever is — mine is only just bad enough to make good work difficult, not enough to hurt appreciably if I don’t try to work. The chocolates reached me — 1000 thanks. Thank you ever so much for the poems of Charlotte Mew: who is she?23 They interested me greatly. I must read them again — they gave me a mood, but my mind was wandering and I don’t know what they were about, I only know the mood they produced. [see next sheet]

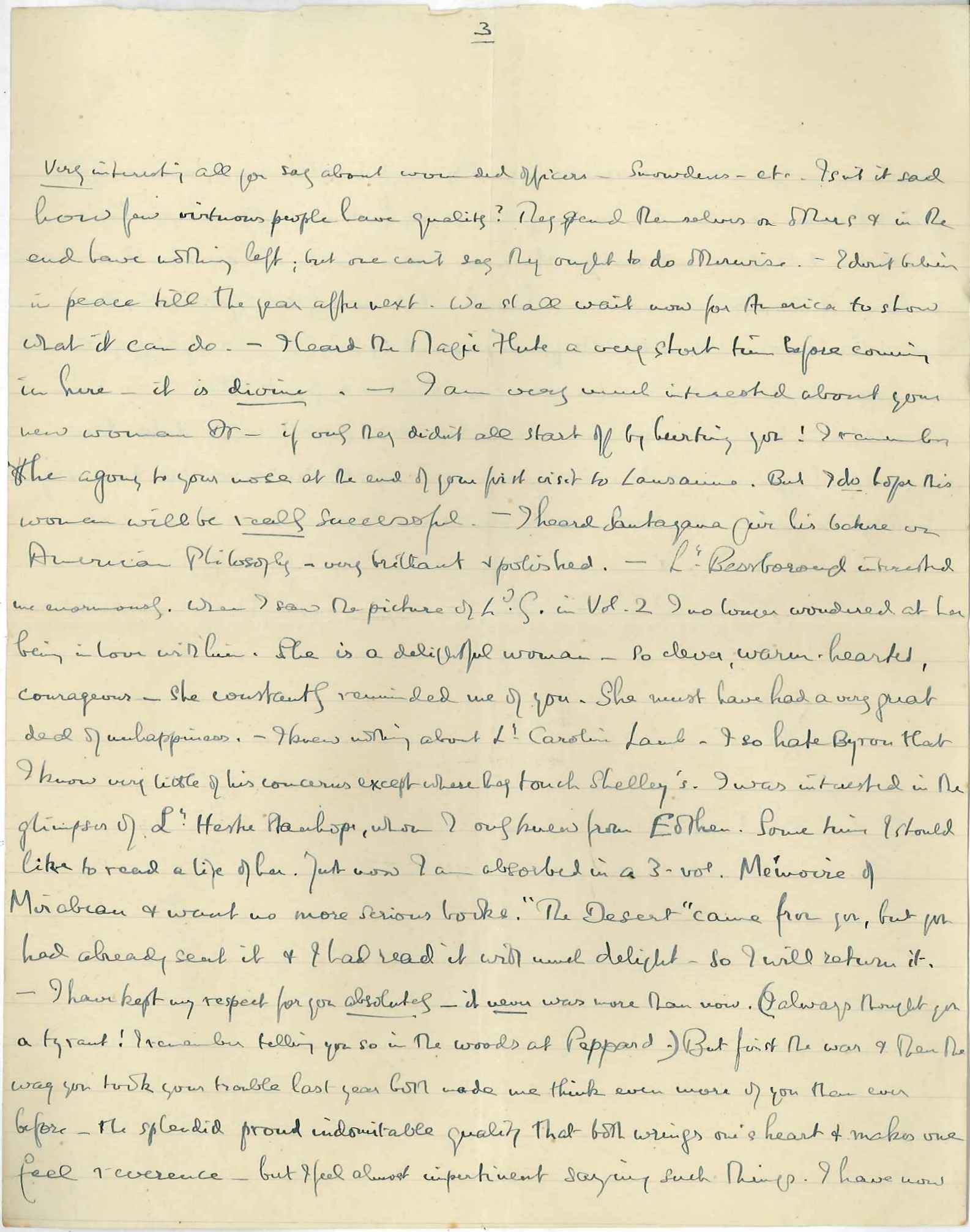

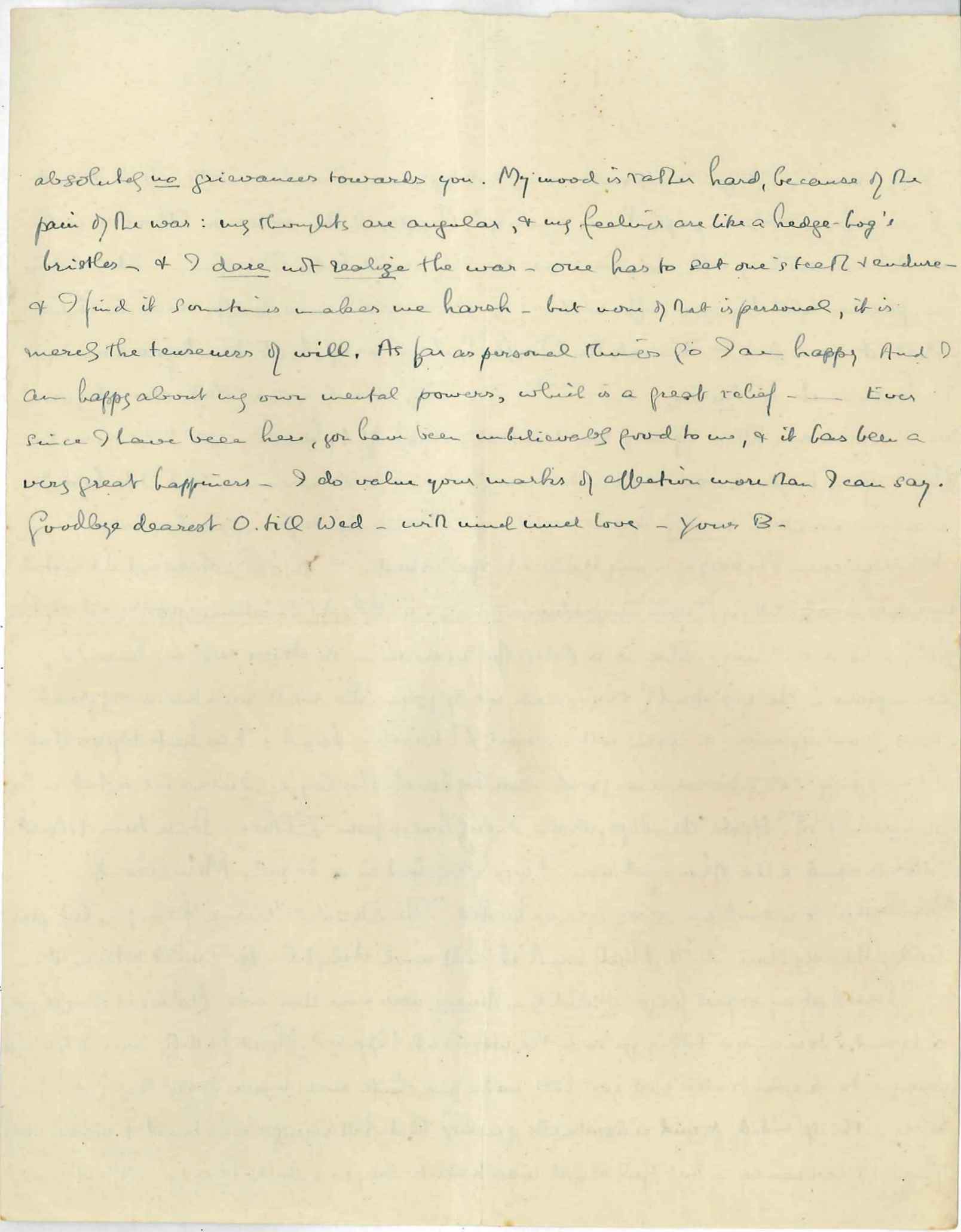

Very interesting all you say about wounded officers — Snowdens24 — etc. Isn’t it sad how few virtuous people have quality? They spend themselves on others and in the end have nothing left; but one can’t say they ought to do otherwise. — I don’t believe in peace till the year after next. We shall wait now for America to show what it can do.25 — I heard the Magic Flute a very short time before coming in here — it is divine.26 — I am very much interested about your new woman Dr — if only they didn’t all start off by hurting you! I remember the agony to your nose at the end of your first visit to Lausanne.27 But I do hope this woman will be really successful. — I heard Santayana give his lecture on American Philosophy — very brilliant and polished.28 — Ly. Bessborough interested me enormously. When I saw the picture of Ld. G. in Vol. 2 I no longer wondered at her being in love with him.29 She is a delightful woman — so clever, warm-hearted, courageous — she constantly reminded me of you. She must have had a very great deal of unhappiness. — I knew nothing about Ly. Caroline Lamb.30 I so hate Byron that I know very little of his concerns except where they touch Shelley’s.31 I was interested in the glimpses of Ly. Hestref Stanhope, whom I only knew from Eothen.32 Some time I should like to read a life of her. Just now I am absorbed in a 3-volume Mémoire of Mirabeau33 and want no more serious books. The Desert34 came from you, but you had already sent it and I had read it with much delight — so I will return it. — I have kept my respect for you absolutely — it never was more than now. I always thought you a tyrant! I remember telling you so in the woods at Peppard.g, 35 But first the war and then the way you took your trouble last year36 both made me think even more of you than ever before — the splendid proud indomitable quality that both wrings one’s heart and makes one feel reverence — but I feel almost impertinent saying such things. I have now absolutely no grievances towards you. My mood is rather hard, because of the pain of the war: my thoughts are angular, and my feelings are like a hedge-hog’s bristles — and I dare not realize the war — one has to set one’s teeth and endure — and I find it sometimes makes me harsh — but none of that is personal, it is merely the tenseness of will. As far as personal things go I am happy. And I am happy about my own mental powers, which is a great relief. — Ever since I have been here, you have been unbelievably good to me, and it has been a very great happiness — I do value your marks of affection more than I can say. Goodbye dearest O. till Wed — with much much love.

Your

B.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from a digital scan of the signed, three-sheet, handwritten and foliated original in the Morrell papers at the University of Texas at Austin. The writing ceased half-way down the verso of each sheet. Each sheet appears to have been separately folded so that the visible quarter-sheets were blank, thus protecting the letter’s privacy. The letter was published as #317 in Vol. 2 of BR’s Selected Letters.

- 2

your letter Dated by BR “late July 1918” and marked “6th letter” (BRACERS 114751).

- 3

P’s letter about S.S. in Nation … looking after mine On 13 July 1918 The Nation published an anonymous and very critical review of Siegfried Sassoon’s Counter-Attack and Other Poems. Ottoline was especially mortified by the review because she knew it was by J. Middleton Murry — she had asked him to write it! Philip Morrell sent an angry letter to the editor (“Mr. Sassoon’s War Verses”, The Nation 23 [20 July 1918]: 418–19). He took aim at the formal fault-finding of orthodox literary criticism in Murry’s review. BR, on 14 July 1918 (Letter 39), also wrote a letter (under the pseudonym “Philalethes”) which he smuggled out to Ottoline, who sent it on to the Nation, taking care that BR’s authorship should not be known. It appeared on 27 July (see also 99 in Papers 14).

- 4

worthlessMansfield’s short story or novella, Prelude, had been published by the Woolfs’ Hogarth Press in July 1918. A copy is in Russell’s library, inscribed to him by Elizabeth Russell. Ottoline also had given BR a copy. Largely plotless, Prelude describes the Burnell family’s move from Wellington to Karori (then on the outskirts of the city) — a move Mansfield’s own family had made in 1893 — revealing the psychology of the characters (especially the women) through the quotidian details of their lives. It marked an important advance in Mansfield’s development as a short-story writer.

- 5

Katherine hates you ... Murry also has to hate S.S. It is by no means easy to see how far this complicated chain of jealousies and recriminations was based in fact and how far it was the result of BR’s inability to keep a rein on his imagination. It is true that in 1916 Murry had told Ottoline, in a remarkably tentative declaration, that he had a “queer suspicion” that he was in love with her (letter of 22 Sept. 1916; quoted in Antony Alpers, The Life of Katherine Mansfield [New York: Viking, 1980], p. 219). It is also true that in August 1917 Murry had visited Garsington without Mansfield and there had been grilled by Ottoline about his relationship with Mansfield. (Ottoline had grilled Mansfield on the same topic in similar circumstances the previous month.) The August meeting kindled a new intimacy between Ottoline and Murry and, it seems, a new boldness in Murry. But if Murry was hoping for an affair with Ottoline, he was destined for disappointment, for Ottoline was still in the throes of her doomed infatuation with Siegfried Sassoon. Although Ottoline didn’t learn of it until early the following year, Murry, perhaps to cover his own advances, had told Mansfield that Ottoline had tried to seduce him. Ottoline did not hold a grudge (witness the fact that she asked Murry to review Sassoon’s Counter-Attack), but Murry and Mansfield did (Miranda Seymour, Ottoline Morrell: Life on the Grand Scale [London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1992], p. 290). None of this, however, supports BR’s elaborate explanation that it was Mansfield’s jealousy of Ottoline that led her to hate Sassoon and make Murry write a critical review. One might suppose that, if jealousy were the motive, it would be Murry’s jealousy of Sassoon, but there seems to be no evidence that either Murry or BR was aware of Ottoline’s romantic interest in Sassoon. The most straightforward explanation is that Murry simply did not like the poems very much. He had conceived the fantasy that he and Mansfield were the authentic voices of English literature, destined to supplant the “strange gods” that “our generation” had “gone whoring after”. Alpers (p. 268) identifies Eliot and Ezra Pound as two of the strange gods — perhaps Murry saw Sassoon as another. BR, however, stuck to a simplified version of his original story: “She hated Ottoline because Murry did not”, he said of Mansfield in his Autobiography (2: 27).

- 6

the Lawrences, a little toned down This comparison seems apt. Katherine Mansfield and J. Middleton Murry were closely associated with Frieda and D.H. Lawrence. They had met, as couples, in 1913 — shortly after Lawrence and Frieda (then Frieda Weekley, née von Richthofen) returned to England after running away to Germany — and the four of them got on almost immediately. Lawrence, who was physically attracted to Murry, proposed that they become blood-brothers — a prospect from which Murry recoiled in alarm. Both couples were always on the move: the Lawrences (they married in July 1914) all over the world and always together; Murry and Mansfield all over England and usually separately. Neither relationship was anything like peaceful. There were rows and separations on the part of Mansfield and Murry, and fights, threats, and violence on the part of the Lawrences. In each relationship the woman, for the most part, called the tune, and, while Lawrence often fought back, Murry typically caved in without a fight. Lawrence recognized these dynamics in Women in Love (written 1916; published 1920) where the two central couples, Birkin and Ursula and Crich and Gudrun, were based on Lawrence and Frieda and Murry and Mansfield, respectively.

- 7

3rd book of Spinoza’s Ethics! Prop. 42 BR probably meant Book III, Prop. 35: “If I imagine that an object beloved by me is united to another person by the same, or by a closer bond of friendship than that by which I myself alone held the object, I shall be affected with hatred towards the beloved object itself, and shall envy that other person.” Prop. 42 of Book III reads: “If, moved by love or hope of self-exaltation, we have conferred a favour upon another person, we shall be sad if we see that the favour is received with ingratitude” (Ethic, trans. W. Hale White and A.M. Stirling, 4th ed. [London: Oxford U. P., 1910; Russell’s library]).

- 8

Those that have appeared in Camb. Mag. Including, most recently, “The General” (7 [13 July 1918]: 868). The Cambridge Magazine, a literary and political weekly that was founded by British linguist C.K. Ogden in 1912 and published BR repeatedly, had published six other poems by Sassoon in the preceding nine months, including one of those (“Glory of Women”) from which BR quoted in Letter 48.

- 9

I like the absence ... reconciliation of discords ... higher harmonyJ. Middleton Murry, by contrast, had taken particular umbrage at the discordant quality of Sassoon’s verse: “We feel not as we do with true poetry or true art that something is, after all, right”, complained his unsigned review of Counter-Attack and Other Poems, “but that something is intolerably and irremediably wrong. And, God knows, something is wrong — wrong with Mr. Sassoon, wrong with the world that has made of him the instrument of a discord so jangling.” In fact, Murry continued, readers had been left by the poet to fashion for themselves “the harmony of which he gives us only the moment of its annihilation” (“Mr. Sassoon’s War Verses”, The Nation 23 [13 July 1918]: 398). Writing to The Nation in defence of Sassoon, as “Philatheles” (see Letter 39), BR concentrated his fire on these objections raised by Murry’s critique.

- 10

gone backSassoon had returned to his regiment in 1917.

- 11

“Love drove me to rebel … hell” From “Banishment” (1917), poem 26 in Sassoon’s Counter-Attack.

- 12

“O German mother … mud” From “Glory of Women” (1917), poem 18 in Sassoon’s Counter-Attack.

- 13

good news as things go On 13 July 1918 Sassoon had been wounded in the head in France — “half an inch of being ‘dead or dotty’”, in the words of the military doctor (as reported by Ottoline: BRACERS 114751) — and was convalescing in Britain.

- 14

I am so glad of all you say about you and me Ottoline had written in the letter BR was answering: “I feel very happy dearest About the future. I feel we have begun a New chapter Now fresh and clean and purged from all the old grievances and all the sharp pins that stuck out. It has been very difficult to be free and spontaneous for a long Time — and that is such a check that it makes one dull and heavy and calculating so as Not to tread on tender spots — but I don’t feel that Now and I feel too such a great sense of intimacy with you. After all we do know each others <sic> inner depths in a way most other people don’t — and it is very wonderful to have come through all the suffering — and all the pain which we have given to each other with absolute unaltered respect and reverence for each other — We have been hurt with each other but never dispised <sic> each other have we? — I don’t feel we found each other essentially ‘wanting’ — which is the thing that leads one to despise anyone. There must have been something that prevented us handling each other in the right way — but that does not mean that there was anything wrong essentially.”

- 15

Slough … “War between Austria and Servia”… Burnham Beeches … the next Tuesday … Aug. 4. Although Serbia accepted all but one condition of a humiliating ultimatum, Austria-Hungary nevertheless declared war on 28 July 1914, exactly a month after the Sarajevo assassination of Archduke Franz-Ferdinand, heir to the Habsburg throne. After the British declaration of war on Germany “the next Tuesday”, 4 August — when BR and Ottoline intended again to visit the scenic Buckinghamshire woodlands of Burnham Beeches — all the major European powers had entered the rapidly widening conflict. After making the journey the previous week, they were presumably greeted with this war news before catching the train from the nearby Berkshire town of Slough to either London or Oxford.

- 16

at Churn On the Berkshire Downs.

- 17

instinct, mind, and spirit In Ch. 7, “Religion and the Churches”, of Principles of Social Reconstruction (London: Allen & Unwin, 1916), BR held that mankind’s activities “derived from three sources”: instinct, mind and spirit. He described the sources in detail (pp. 205–7). Instinct, which BR and Ottoline did not share, is concerned with “self-preservation and reproduction” and “vanity and love of possessions, love of family, and even much that makes love of country”. The life of the mind concerns the pursuit of knowledge. Knowledge has proven to be very useful, but “direct love” of it and “dislike of error” still play a large part in the activity of “impersonal” thought. Spirit, which he said they had in common, generates religion.

- 18

I did not speak of C.M. BR told Ottoline of his affair with Colette only in the late summer of 1917, almost a year after it started (R. Gathorne-Hardy, ed., Ottoline at Garsington: Memoirs of Lady Ottoline Morrell, 1915–1918 [London: Faber and Faber, 1974], p. 178).

- 19

Mother Julian’s Bird “A picture which now hangs over my mantlepiece.” (BR’s note at BRACERS 119462.) Mother Julian (Julian Jane Jemima Maitland Warrender [1827–1911], Mother Superior of the Community of the Epiphany) had been Ottoline’s spiritual mentor. She had given Ottoline a painting of a dove, which became BR’s when Ottoline died. BR’s unexpected respect for Mother Julian’s memory was perhaps in remembrance of Ottoline’s contribution of the Nun’s speech in “The Perplexities of John Forstice” (1912; Papers 12: 149–51), a speech for which the original manuscript is in Ottoline’s hand (BRACERS 113797).

- 20

Matter … before the war BR worked on matter at Churn in Moulsford, September 1912, and at the Beetle and Wedge (also in Moulsford) in December 1912–January 1913. The results were posthumously published (10, 11 inPapers 6). Eventually this work led to Our Knowledge of the External World (1914) and “The Relations of Sense-Data to Physics” (1914; 1 inPapers 8).

- 21

Chappelow Eric Barry Wilfred Chappelow (1890–1957), a poet and C.O., on whose behalf BR had tried unsuccessfully to intercede after his detention in military custody in 1916. BR described him as “unduly sentimental”. In 1916 Chappelow published Joy and the Year, and Other Poems (London: Selwyn & Blount). See Jo Vellacott, Bertrand Russell and the Pacifists in the First World War (Brighton: Harvester P., 1980), pp. 60–1; https://ww1richmond.wordpress.com/2016/02/17/conscientious-objection-er….

- 22

medical officer The medical officer signed a form dated 14 August 1918 with his initials, G.A.G.

- 23

Mew: who is she? Charlotte Mew (1869–1928), a poet whose bitterly unhappy life ended in suicide. She published very little, and BR must have been reading The Farmer’s Bride (1916), her only book. The main themes of its poems are loneliness, death, madness, and the fragile consolations of religion.

- 24

wounded officers — Snowdens Each week Ottoline and Philip had five wounded soldiers to stay at Garsington. She had recounted how one of them had seen the Snowdens’ names in the guest-book and said: “Sound stuff he writes in the Labour Leader” — a weekly publication of the Independent Labour Party, for which its anti-war chairman, Philip Snowden (1864–1937), wrote a regular column entitled “Review of the Week”. Ottoline praised Snowden and his wife, Ethel (1880–1951), as “a very fine couple” but also dissected Philip’s intellectual shortcomings for BR’s benefit: “I don’t get at very much except splendid integrity and pure politics. He does not seem to speculate or to break up ideas — only to think on straight forward lines” (BRACERS 114751). As M.P. for Blackburn, Snowden was one of the C.O. movement’s most vocal parliamentary champions. BR also admired him but was frustrated by his political caution (see Papers 13: 581). Ethel Snowden was a leading pacifist, socialist and suffragist in her own right; in 1920 she was part of the British Labour Delegation to Russia and, like BR, returned with a dim view of the revolutionary regime.

- 25

America to show what it can do The onset of American military intervention in April 1917 had a far from immediate impact on the Allied war effort. The United States had only a small standing army, and it took months to achieve a mass-mobilization after conscription legislation was passed by Congress in May 1917. Although the first American soldiers arrived in France as early as June 1917, US troop-levels there remained small until the following year. The 284,000 Americans on active duty by the end of March 1918, however, played a major role in repulsing Germany’s last major offensive of the war, and with reinforcements beginning to arrive at the rate of 10,000 per day, American military might was also crucial to the success of the Allied operations in the summer to which BR occasionally alluded in prison (e.g. Letters 60 and 75). Ultimately four million men were drafted into the American armed forces by the Selective Service Act, about half of whom were deployed on the Western Front.

- 26

it is divine Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute was in repertory at the Theatre Royal, as part of Thomas Beecham’s “Summer Season of Grand Opera in English”. Ottoline had just been to hear it.

- 27

woman Dr. … Lausanne In 1912 Ottoline went to Lausanne to be treated by a Dr. Combe, who operated, most painfully, on her nose. Ottoline’s new woman doctor had decided that her headaches were caused by troubles in her nose and throat. The new doctor was Dr. Sayers (BRACERS 114751), who was a great friend of H.W. Massingham “and cured him” of an unspecified ailment.

- 28

Santayana … polished The lecture “The Genteel Tradition in American Philosophy” was published in Santayana’s Winds of Doctrine (1913) and was originally given in California in 1911. It is not known when BR heard it.

- 29

in love with him At Ottoline’s suggestion BR was reading the Private Correspondence of Lord Granville Leveson-Gower (1773–1846), edited by his daughter-in-law (2 vols., London: J. Murray, 1917). Lord Granville was a Tory politician turned diplomat, who married into one of the great Whig families, the Cavendishes. A younger son of the Marquess of Stafford, he was elevated to the peerage in his own right as Viscount Granville in 1815 and received an earldom in 1833. Many of the letters included in the collection BR was reading were between him and Henrietta Francis, Lady Bessborough (1761–1821), his mistress, with whom he had two children. Her letters reveal all the virtues BR mentions. She was evidently devoted to Granville, who, from his letters, appears superficial and foppish. BR had wondered (Letter 40) how she could love “such a stick”. The frontispiece of volume 2 gives the answer: he was very good-looking — though a contemporary thought he had “too much of a fair, soft, sweet sort of beauty”.

- 30

Ly. Caroline Lamb Lady Caroline Lamb (1785–1828) was Lady Bessborough’s daughter by her marriage to the Earl of Bessborough. She married William Lamb, Viscount Melbourne, in 1805 but is best known for her affair with Lord Byron in 1812–13.

- 31

I so hate Byron … Shelley’s While the young BR found the verse of Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822) “intoxicating”, he was repelled by the “jingling, mechanical metres” of George Gordon, 6th Baron Byron (1788–1824) (“The Importance of Shelley” [1957]; Papers 29: 77–8). In the 1930s BR became interested in establishing the philosophical lineage from Byronic romanticism to the disturbing currents of contemporary political irrationalism (“Byron and the Modern World”; 54 in Papers 21).

- 32

Eothen Lady Hester Stanhope (1776–1839), English traveller and eccentric. Adopting Eastern dress, she travelled with the Bedouin and eventually settled on Mt. Lebanon, where she created her own religion based on astrology. The tribes among whom she lived thought her divinely inspired, and towards the end of her life, she seems to have agreed with them. Her life on Mt. Lebanon was described by Alexander Kinglake in Eothen, or Traces of Travel Brought Home from the East (1844).

- 33

Mirabeau Honoré-Gabriel Riqueti, Comte de Mirabeau (1749–1791), a French aristocrat rejected by his class who became, despite his moderate views, an important leader of the revolutionary National Assembly. It is not known which Mémoire BR was reading, Mirabeau’s personal Mémoires having been published in several volumes.

- 34

The Desert Probably Mogu, The Wanderer, or The Desert (1917), a play by Padraic Colum.

- 35

woods at Peppard In south Oxfordshire, about twenty miles south-east of Lady Ottoline and Philip Morrell’s later country house, Garsington Manor. The Morrells lived at Peppard Cottage before moving to Garsington. BR visited her often at Peppard in July 1911 and did much writing (The Problems of Philosophy and a lost work on philosophy of religion) there that month.

- 36

your trouble last year In 1917 Ottoline learnt of Philip’s more consequential infidelities, when her maid and his secretary were both pregnant by him. The crisis completely unnerved Philip, who had to be put in a nursing home. See Miranda Seymour, Ottoline Morrell: Life on the Grand Scale (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1998), pp. 382–4.

Textual Notes

- a

(Not only … on.) Inserted.

- b

Prelude Initial cap and italics editorially supplied.

- c

physical Inserted before “affection”.

- d

all right. A wide space on the line was left before “Do you remember”, which is therefore regarded editorially as the start of a new paragraph.

- e

or retrospect Inserted.

- f

Hestre BR misspelt her first name, which was “Hester”.

- g

I always … woods at Peppard. The parentheses drawn around this sentence are judged to be non-authorial, similar to other pairs of parentheses that were part of Ottoline’s editing of the letters for her own purposes.

Annotations by BR

In the late 1940s, when BR was going through his archives, and in the 1950s when he was revising his Autobiography, he would occasionally annotate letters. He did this to sixteen of the Brixton letters. Links to them are gathered here for convenient access to these new texts. In the annotations to the letters they are always followed by “(BR’s note.)”

Letter 2, note 5 happy.

5, note 6 congratulations to G.J.

9, note 28 bit of Girondin history.

12, note 6 friend.

15, note 2 (the letter in general).

20, note 7 G.J.

31, note 3 Dr’s treatment.

40, notes 9, 10 Ld. G.L.G, Lady B’s.

44, note 14 S.S.

48, note 48 Mother Julian’s Bird.

57, notes 13, 16 Ld. Granville’s to Ly. B., bless that Dr. … seat of intellect.

70, note 15 Mrs Scott.

73, note 12 E.S.P. Haynes.

76, note 4 Cave.

85, note 2 Marsh on Rupert.

102, notes 23, 28 Woolley, K. Lonsdale.

General Annotations

Brett note from Auto. 2: 93

Cousens note from Auto. 2: 71

Kyle note with her letters to BR

Rinder note from Auto. 2: 88n.

Silcox note on BRACERS 80365

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.

Elizabeth Russell

Elizabeth Russell, born Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941), was a novelist who in 1891 married Graf von Arnim-Schlagenthin. She became known as “Elizabeth”, the name she used in publishing Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898), and she remained widely known as Elizabeth von Arnim, although the Library of Congress catalogues her as Mary Annette (Beauchamp), Countess von Arnim. She was a widow when she married BR’s brother, Frank, on 11 February 1916. The marriage was quickly in difficulty; she left it for good in March 1919, but they were never divorced and she remained Countess Russell (becoming Dowager Countess after Frank’s death in 1931).

H.W. Massingham

H.W. Massingham (1860–1924), radical journalist and founding editor in 1907 of The Nation, a publication which superseded The Speaker and soon became Britain’s foremost Liberal weekly. Almost immediately the editor of the new periodical started to host a weekly luncheon (usually at the National Liberal Club), which became a vital forum for the exchange of “New Liberal” ideas and strategies between like-minded politicians, publicists and intellectuals (see Alfred F. Havighurst, Radical Journalist: H.W. Massingham, 1860–1924 [Cambridge: U. P., 1974], pp. 152–3). On 4 August 1914, BR attended a particularly significant Nation lunch, at which Massingham appeared still to be in favour of British neutrality (see Papers 13: 6) — which had actually ended at the stroke of midnight. By the next day, however, Massingham (like many Radical critics of Britain’s pre-war diplomacy) had come to accept the case for military intervention, a position he maintained (not without misgivings) for the next two years. Massingham was still at the helm of the Nation when it merged with the more literary-minded Athenaeum in 1921; he finally relinquished editorial control two years later. In 1918 he served on Miles and Constance Malleson’s Experimental Theatre Committee.

J. Middleton Murry

J. Middleton Murry (1889–1957), critic and editor, was educated in classics at Brasenose College, Oxford, before establishing in 1911 the short-lived avant-garde journal, Rhythm. In May 1918 he married the author Katherine Mansfield, to whose literary legacy he became devoted after her death from tuberculosis only five years later. The couple were frequent visitors to Garsington Manor, and Murry appears at one time to have had a romantic yearning for Ottoline (see note to Letter 48). Although Murry’s scornful treatment of Sassoon’s poetry annoyed BR (see Letter 39), he became, nevertheless, a frequent contributor to The Athenaeum during Murry’s two-year stint as its editor (1919–21). After the ailing literary weekly merged with The Nation in 1921, Murry continued his vigorous promotion of modernism in the arts from the helm of his own monthly journal, The Adelphi, which he edited for 25 years. During the First World War he worked as a translator for the War Office but became an uncompromising pacifist in the 1930s. One of the last assignments of his journalistic career was as editor of the pacifist weekly, Peace News (1940–46). Source: Oxford DNB.

Katherine Mansfield

Katherine Mansfield (1888–1923), pseudonym of Kathleen Mansfield Beauchamp, New Zealand-born short-story writer. After studying music in her native country, Mansfield moved to London in 1908, married George Bowden, a music teacher, whom she left after a few days, the marriage unconsummated. She was at the time pregnant from a previous affair. Her experiences in Bavaria, where the child was stillborn, became the background for her first collection of stories, In a German Pension (1911), most of which had been previously published in A.R. Orage’s journal, The New Age. In 1911 she met J. Middleton Murry, who fell quickly under her spell and with whom she was to be associated until the end of her life, though they frequently lived independently and married only in 1918. Her health had long been fragile, and in 1918 she was diagnosed with the tuberculosis which eventually killed her. BR met her in 1916 when she was living in Gower Street, near BR’s brother’s house in Gordon Square. For a short time they had an intimate friendship, but not an affair. BR found her talk, especially about what she planned to write, “marvellous, much better than her writing”. But “when she spoke about people she was envious, dark and full of alarming penetration in discovering what they least wished known.” She spoke in this vein of Ottoline Morrell. BR listened but in the end “believed very little of it” and, after that, saw Mansfield no more (Auto. 2: 27). Main biography: Antony Alpers, The Life of Katherine Mansfield (New York: Viking, 1980).

Philip Morrell

Philip Morrell, Ottoline’s husband (1870–1943), whom she had married in 1902 and with whom, four years later, she had twins — Julian, and her brother, Hugh, who died in infancy. The Morrells were wealthy Oxfordshire brewers, although Philip’s father was a solicitor. He won the Oxfordshire seat of Henley for the Liberal Party in 1906 but held this Conservative stronghold only until the next general election, four years later. For the second general election of 1910 he ran successfully for the Liberals in the Lancashire manufacturing town of Burnley. But Morrell’s unpopular anti-war views later cost him the backing of the local Liberal Association, and his failure to regain the party’s nomination for the post-war election of 1918 (see Letter 89) effectively ended his short political career. Unlike many other Liberal critics of British war policy (including BR), Morrell did not transfer his political allegiance to the Labour Party. Although Ottoline and her husband generally tolerated each other’s extra-marital affairs, a family crisis ensued when in 1917 Philip impregnated both his wife’s maid and his secretary (see Letter 48).

Siegfried Sassoon

Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967), soldier awarded the MC and anti-war poet. Ottoline had befriended him in 1916, and the following year, when Sassoon refused to return to his regiment after being wounded, she and BR helped publicize this protest, which probably saved him from a court martial. BR even assisted Sassoon in revising his famous anti-war statement, which was read to the House of Commons by a Liberal M.P. on 30 July 1917. Sassoon’s actions were an embarrassment to the authorities, for he was well known as both a poet and a war hero. Unable to hush the case up, the government acted with unexpected subtlety and declared Sassoon to be suffering from shell-shock and sent him to Craiglockhart War Hospital for Officers, near Edinburgh. After a period of recuperation in Scotland overseen by military psychiatrist Capt. W.H.R. Rivers, Sassoon decided to return to the Front (see Jean Moorcroft Wilson, Siegfried Sassoon: Soldier, Poet, Lover, Friend [New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2014]). He was again wounded in July 1918 and was convalescing in Britain during some of BR’s imprisonment. Although each admired the other’s stand on the war, BR and Sassoon were never close in later years. Yet Sassoon did pledge £50 to the fellowship plan fund (see BRACERS 114758), and decades later he donated a manuscript in support of BR’s International War Crimes Tribunal (see BRACERS 79066).

T.S. Eliot

The poet and critic Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888–1965) was a student of BR’s at Harvard in 1914. BR had sensed his ability, especially “a certain exquisiteness of appreciation” (to Lucy Donnelly, 11 May 1914; SLBR 1: 491), but did not see a genius in embryo. After Eliot travelled to England later the same year, to study philosophy at Oxford under H.H. Joachim, BR became something of a father figure to the younger man. He also befriended Eliot’s (English) wife, Vivienne, whom he had hastily married in 1915 and with whom BR may have had an affair the following year. BR shared his Bloomsbury apartment (at 34 Russell Chambers) with the couple for more than a year after their marriage, and jointly rented a property with them in Marlow, Bucks. (see Letter 78). He further eased Eliot’s monetary concerns by arranging paid reviewing for him and giving him £3,000 in debentures from which BR was reluctant, on pacifist grounds, to collect the income (Auto. 2: 19). Eliot’s financial security was much improved by obtaining a position at Lloyd’s Bank in 1917, but during BR’s imprisonment he faced uncertainty of a different kind as the shadow of conscription loomed over him (see, e.g., Letter 27). Nine years after the war ended Eliot returned the securities (BRACERS 76480).

The Nation

A political and literary weekly, 1907–21, edited for its entirety by H.W. Massingham before it merged with The Athenaeum and then The New Statesman. BR regularly contributed book reviews, starting in 1907. During his time at Brixton, he published there a book review (14 in Papers 8; mentioned in Letters 4 and 102) and a letter to the editor (Letter 39). In August 1914 The Nation hastily abandoned its longstanding support for British neutrality, rejecting an impassioned defence of this position written by BR on the day that Britain declared war (1 in Papers 13). For the next two years the publication gave its editorial backing (albeit with mounting reservations) to the quest for a decisive Allied victory. At the same time, it consistently upheld civil liberties against the encroachments of the wartime state, and by early 1917 had started calling for a negotiated peace as well. The Nation had recovered its dissenting credentials, but for allegedly “defeatist” coverage of the war was hit with an export embargo imposed in March 1917 by Defence of the Realm Regulation 24B.

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.