Brixton Letter 45

BR to Constance Malleson

July 22, 1918

- AL

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-45

BRACERS 19324

<Brixton Prison>1

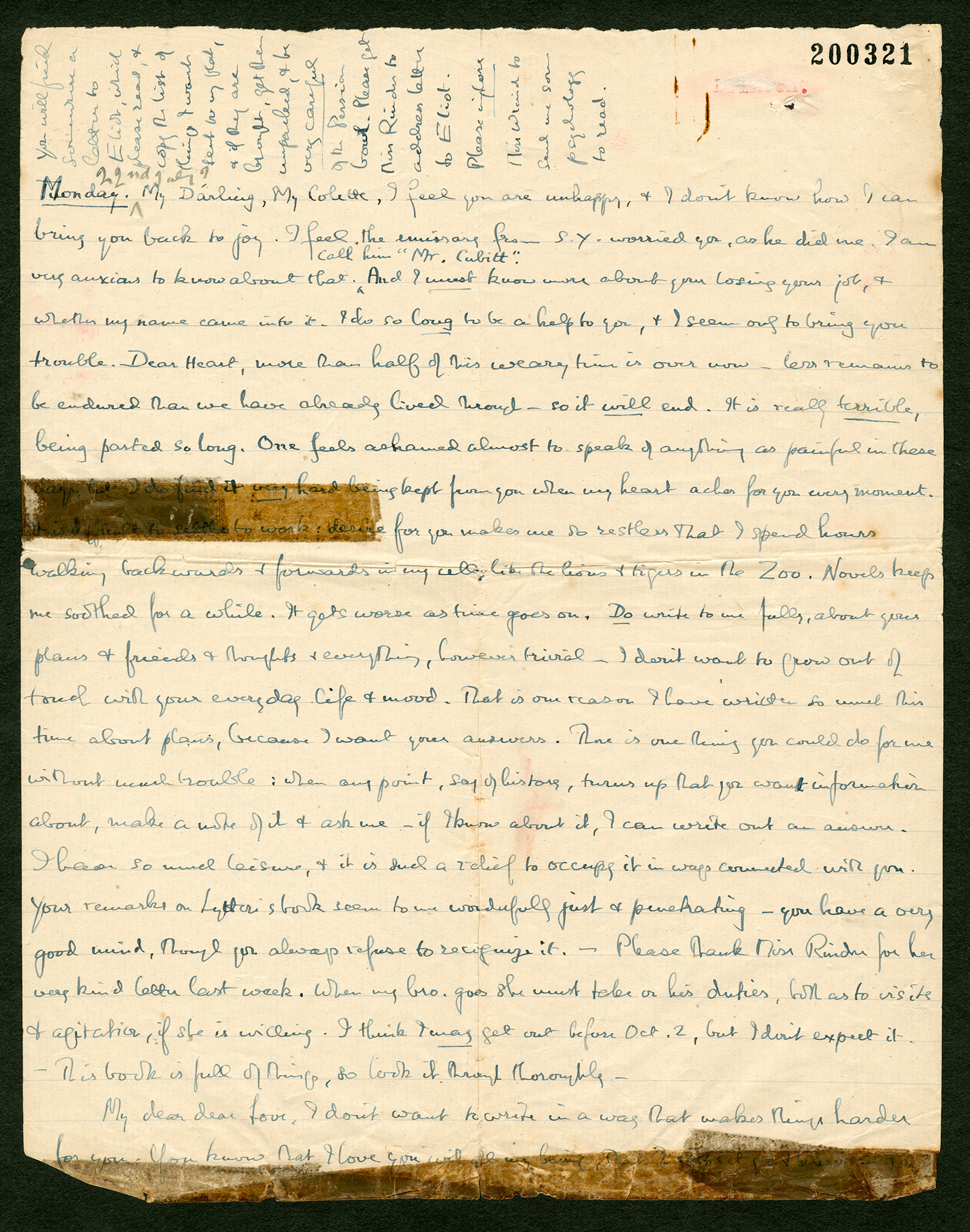

Monday.2

My Darling, My Colette,

I feel you are unhappy, and I don’t know how I can bring you back to joy. I feel the emissary from S.Y.3 worried you, as he did me. I am very anxious to know about that. Call him “Mr. Cubitt”.a And I must know more about your losing your job, and whether my name came into it.4 I do so long to be a help to you, and I seem only to bring you trouble. Dear Heart, more than half of this weary time is over5 now — less remains to be endured than we have already lived through — so it will end. It is really terrible, being parted so long. One feels ashamed almost to speak of anything as painful in these days; but I do find it very hard being kept from you when my heart aches for you every moment. It is difficult to settle to work: desire for you makes me so restless that I spend hours walking backwards and forwards in my cell, like the lions and tigers in the Zoo. Novels keep me soothed for a while. It gets worse as time goes on. Do write to me fully, about your plans and friends and thoughts and everything, however trivial — I don’t want to grow out of touch with your everyday life and mood. That is one reason I have written so much this time about plans,6 because I want your answers. There is one thing you could do for me without much trouble: when any point, say of history, turns up that you want information about, make a note of it and ask me — if I know about it, I can write out an answer.7 I have so much leisure, and it is such a relief to occupy it in ways connected with you. Your remarks on Lytton’s book8 seem to me wonderfully just and penetrating — you have a very good mind, though you always refuse to recognize it. — Please thank Miss Rinder for her very kind letter last week.9 When my brother goes10 she must take on his duties, both as to visits and agitation, if she is willing. I think I may get out before Oct. 2,11 but I don’t expect it. — This book is full of things, so look it through thoroughly.12

My dear dear Love, I don’t want to write in a way that makes things harder for you. You know that I love you with all my being, that I respect you and believe in you. This is a hard time for the world — less so for you and me than for most people. We want to emerge from this time with the faculty for work and for joy unimpaired — that is in a way a matter of courage and grit — not the steely courage that leaves one rather inhuman, but something more gay. It is the world’s need that one has to bear in mind. I feel our love all bound up with the world’s need — it is through our love that I find it possible to keep hope alive, and to be ready to lead young men and women on paths of intellectual adventure when the time comes. And I want you to feel the same sort of thing: a firm resolve not to be crushed by the burden — the war, the police, lack of work, all tries to weigh you down, and your victory is to remain full of happiness and life. This time is a fiery test for us all, but you and I will come through it, Beloved — for our own sakes and for the world’s. My dear, my dear, all that is deepest in me is bound to you indissolubly.

You will find somewhere a letter to Eliot,13 which please read, and copy the list of things I want sent to my flat, and if they are brought, get them unpacked, and be very careful of the Persian bowl.14 Please get Miss Rinder to address letter to Eliot. Please implore Miss Wrinch to send me some psychology to read.b, 15

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the unsigned, handwritten original in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. It is written on both sides but only half-way down the verso of each of the two sheets of thin, laid paper, ruled on one side and folded twice, so that there was no writing on the exposed quarters of the sheets.

- 2

[date] “22nd July?” is written by Colette following the day.

- 3

emissary from S.Y. BR had written about the incident involving Scotland Yard in the letter dated [20 July 1918] (Letter 42). There he was more oblique, referring to the man as “the inquisitive emissary from Ireland Cubitt”. “Ireland” evokes “Scotland”, and a “cubitt” is a length (that of a forearm) — which was BR’s way of disguising any mention of “Scotland Yard”.

- 4

your losing your job, and whether my name came into it In Letter 43 BR had written: “Please let me know more about the row that lost you your tour. Was Miles’s pacifism the trouble, or had they caught on to me?” In her letter of 26 July (BRACERS 113145), Colette explained it as follows: “Miles had seen a great deal of Marie <Blanche> at her theatre; and her manager — that same infernal big-wig — dislikes Miles and his politics; and my politics, of course, too. So his general displeasure got vented on me, as he’d not wish to vent it on Marie, and couldn’t vent it on Miles. Of course you didn’t come into it at all.” BR must not yet have received this reply of Colette’s and so repeated the question.

- 5

more than half of this weary time is over Since BR entered prison on 1 May, this calculation (totalling c.83 days so far) implies that he anticipated serving about five months rather than the six to which he had been nominally sentenced. He expected to be released (for good conduct) on 2 October. See note 7 to Letter 24.

- 6

I have written so much this time about plans This must be a reference to Letter 42.

- 7

I can write out an answer An example is his letter of 10 August 1918 (Letter 64), in which he answered her question about a good biography of his grandfather Lord John Russell and wrote also about the Bible. Another example is “The Single Tax” (101 inPapers 14), which he seems to have sent her about 28 August (Letter 86).

- 8

Your remarks on Lytton’s book BR first praised Colette’s remarks on Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians in Letter 44. See note 4 in that letter for the remarks.

- 9

her very kind letter last week It may be Rinder’s undated letter at BRACERS 79623, dated July 1918 there (sometime after 11 July when the ban on visiting prohibited areas was lifted for BR; but more narrowly after 17 July when Frank was informed of the ban’s lifting).

- 10

my brother goesFrank Russell was leaving London for his country home, Telegraph House.

- 11

may get out before Oct. 2 The date of his anticipated early release from Brixton.

- 12

This book is full of things, so look it through thoroughly. It contained more than one letter.

- 13

a letter to Eliot The letter is not extant. T.S. Eliot did, however, come to tea with Colette at her flat, perhaps to make arrangements about BR’s things (After Ten Years [London: Cape, 1931], pp. 126–7).

- 14

Persian bowl “Would you also perhaps say that your Persian bowl had been (and is) your most important objet d’art?” Colette posed this question in her letter of 2 January 1950 (BRACERS 98449). In his letter of 11 September 1918 (Letter 103), BR asked Colette to put the Persian bowl on its ebony stand on the mantelpiece in place of a bust of Voltaire.

- 15

send me some psychology to read Colette wrote on 3 August 1918 that she hoped Dorothy Wrinch “has by now sent the psychology you wanted, or that Hardy may have done so” (BRACERS 113147).

Textual Notes

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Catherine E. Marshall

Catherine E. Marshall (1880–1961), suffragist and internationalist who after August 1914 quickly moved from campaigning for women’s votes to protesting the war. An associate member of the No-Conscription Fellowship, she collaborated closely with BR during 1917 especially, when she was the organization’s Acting Hon. Secretary and he its Acting Chairman. Physically broken by a year of intense political work on behalf of the C.O. community, Marshall then spent several months convalescing with the NCF’s founding chairman, Clifford Allen, after he was released from prison on health grounds late in 1917. According to Jo Vellacott, Marshall was in love with Allen and “suffered deeply when he was imprisoned”. During his own imprisonment BR heard rumours that Marshall was to marry Allen (e.g., Letter 71), and Vellacott further suggests that the couple lived together during 1918 “in what seems to have been a trial marriage; Marshall was devastated when the relationship ended” (Oxford DNB). Throughout the inter-war period Marshall was active in the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

Dorothy Wrinch

Dorothy Maud Wrinch (1894–1976), mathematician, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. She studied mathematics and philosophy at Girton College, Cambridge, and came under BR’s influence in her second year when she took his course on mathematical logic. She taught mathematics at University College, London, 1918–21, and then at Oxford, 1922–30. Her first publications were in mathematical logic and philosophy, and during the 1920s she wrote on the philosophy of science. But in the 1930s her interests turned to mathematical biology and crystallography, and in 1935 she moved to the United States on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship and remained there for the rest of her life. Unfortunately, as a biologist she is best known for a long and stubborn controversy with Linus Pauling about the structure of proteins in which he was right and she was wrong. See Marjorie Senechal, I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science (New York: Oxford U. P., 2013). Chapter 7 is devoted to Wrinch’s interactions with BR in Brixton.

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Lytton Strachey

Lytton Strachey (1880–1932), biographer, reviewer and a quintessential literary figure of the Bloomsbury Group. He is best known for his debunking portraits of Cardinal Manning, Florence Nightingale, Dr. Arnold and General Gordon, published together as Eminent Victorians (London: Chatto & Windus, 1918; Russell’s library), which BR read in Brixton with great amusement as well as some critical reservations (see Letter 7). Although Strachey was homosexual, he and the artist Dora Carrington were devoted to each other and from 1917 lived together in Tidmarsh, Berkshire. BR had become acquainted with the somewhat eccentric Strachey, a fellow Cambridge Apostle, while his slightly younger contemporary was reading history at Trinity College. He admired Strachey’s literary gifts, but doubted his intellectual honesty. Almost three decades later BR fleshed out the unflattering thumbnail of Strachey drawn for Ottoline in Letter 7, in a “Portrait from Memory” for BBC radio. Strachey was “indifferent to historical truth”, BR alleged in that broadcast, “and would always touch up the picture to make the lights and shades more glaring and the folly or wickedness of famous people more obvious” (The Listener 48 [17 July 1952]: 98). Main biography: Michael Holroyd, Lytton Strachey: a Critical Biography, 2 vols. (London: Heinemann, 1967–68).

Marie Blanche

Marie Blanche (1891–1973) studied at the Academy of Dramatic Arts where she met Colette. She sang as well as acted and had a successful career on the London stage in the 1920s. A photograph of her appeared in The Times, 20 March 1923, p. 16.

Miles Malleson

Miles Malleson (1888–1969), actor and playwright, was born in Croydon, Surrey, the son of Edmund and Myrrha Malleson. He married his first wife, a fellow actor, Lady Constance Annesley (stage name, Colette O’Niel), in 1915. They had met at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts). Their marriage was an “open” one. In 1914 Miles enlisted in the City of London Fusiliers and was sent to Malta. He became ill and was discharged, unfit for further service. He became active in the No-Conscription Fellowship and wrote anti-war stage plays as well as a pamphlet, Cranks and Commonsense (1916). In the 1930s he began to write for the screen and act in films, in which he became a very well-known character actor, as well as continuing his stage career at the Old Vic in London. He married three times: his second marriage was to Joan Billson, a physician (married 1923, divorced 1940), with whom he had two children; his third wife was Tatiana Lieven, an actress (married 1946). He died in London in March 1969.

Prohibited areas

On 17 July 1918 (BRACERS 75814) General George Cockerill, Director of Special Intelligence at the War Office, notified Frank Russell that constraints on BR’s freedom of movement, imposed almost two years before, had been lifted as of 11 July. Since 1 September 1916, BR had been banned under Defence of the Realm Regulation 14 from visiting any of Britain’s “prohibited areas” without the express permission of a “competent military authority”. The extra-judicial action was taken partly in lieu of prosecuting BR for a second time under the Defence of the Realm Act, on this occasion over an anti-war speech delivered in Cardiff on 6 July 1916 (63 in Papers 13). (Britain’s Director of Public Prosecutions was confident that a conviction could be secured but concerned lest BR should again exploit the trial proceedings for propaganda effect and thereby create “a remedy … worse than the disease” [HO 45/11012/314760/6, National Archives, UK].) Since the exclusion zone covered many centres of war production, BR would be prevented (according to the head of MI5) from spreading “his vicious tenets amongst dockers, miners and transport workers” (quoted in Papers 13: lxiv). But the order also applied to military and naval installations and almost the entire coastline. As a lover of the sea and the seaside, BR chafed under the latter restriction: “I can’t tell you how I long for the SEA”, he told Colette (Letter 75).

Russell Chambers

34 Russell Chambers, Bury Street (since renamed Bury Place), London WC1, BR’s flat since 1911. Helen Dudley rented the flat in late 1916 or early 1917. In May 1918 she sublet it to Clare Annesley. Colette moved in on 9 September 1918 and stayed until June 1919. BR did not give up the lease until December 1923. See S. Turcon, “Russell Chambers, Other London Flats, and Country Homes, 1911–1923”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 150 (Fall 2014): 30–4. “Russell Chambers, Other London Flats, and Country Homes, 1911–1923”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 150 (Fall 2014): 30–4.

T.S. Eliot

The poet and critic Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888–1965) was a student of BR’s at Harvard in 1914. BR had sensed his ability, especially “a certain exquisiteness of appreciation” (to Lucy Donnelly, 11 May 1914; SLBR 1: 491), but did not see a genius in embryo. After Eliot travelled to England later the same year, to study philosophy at Oxford under H.H. Joachim, BR became something of a father figure to the younger man. He also befriended Eliot’s (English) wife, Vivienne, whom he had hastily married in 1915 and with whom BR may have had an affair the following year. BR shared his Bloomsbury apartment (at 34 Russell Chambers) with the couple for more than a year after their marriage, and jointly rented a property with them in Marlow, Bucks. (see Letter 78). He further eased Eliot’s monetary concerns by arranging paid reviewing for him and giving him £3,000 in debentures from which BR was reluctant, on pacifist grounds, to collect the income (Auto. 2: 19). Eliot’s financial security was much improved by obtaining a position at Lloyd’s Bank in 1917, but during BR’s imprisonment he faced uncertainty of a different kind as the shadow of conscription loomed over him (see, e.g., Letter 27). Nine years after the war ended Eliot returned the securities (BRACERS 76480).

Telegraph House

Telegraph House, the country home of BR’s brother, Frank. It is located on the South Downs near Petersfield, Hants., and North Marden, W. Sussex. See S. Turcon, “Telegraph House”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 154 (Fall 2016): 45–69.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.