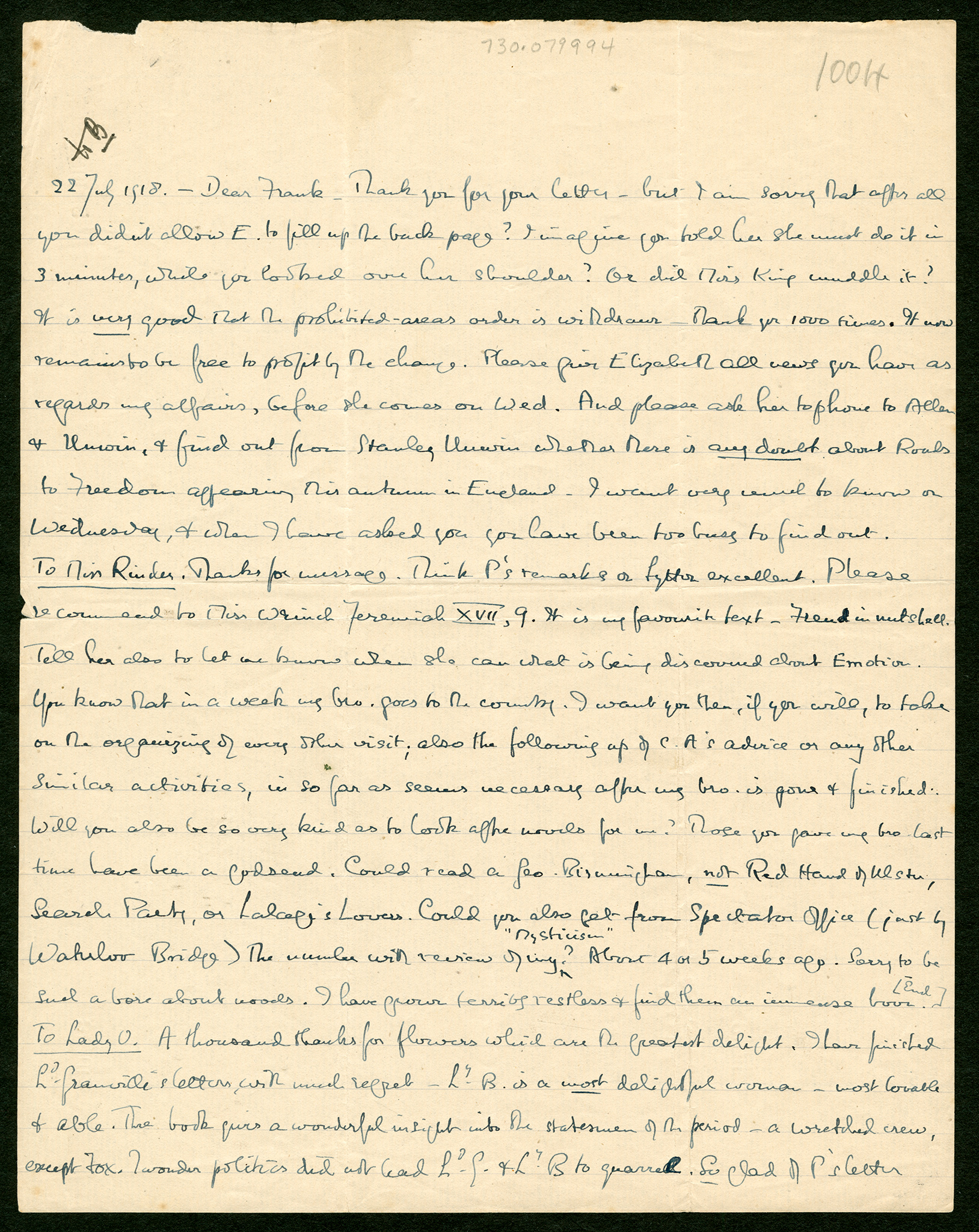

Brixton Letter 44

BR to Frank Russell

July 22, 1918

- ALS

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-44

BRACERS 46928

<Brixton Prison>1

22 July 1918.

Dear Frank

Thank you for your letter2 — but I am sorry that after all you didn’t allow E. to fill up the back page? I imagine you told her she must do it in 3 minutes, while you looked over her shoulder? Or did Miss King3 muddle it? It is very good that the prohibited-areas order is withdrawn — thank you 1000 times. It now remains to be free to profit by the change. Please give Elizabeth all news you have as regards my affairs, before she comes on Wed. And please ask her to phone to Allen and Unwin, and find out from Stanley Unwin whether there is any doubt about Roads to Freedom appearing this autumn in England. I want very much to know on Wednesday, and when I have asked you you have been too busy to find out. To Miss Rinder. Thanks for message. Think P’s remarks on Lytton4 excellent. Please recommend to Miss Wrinch Jeremiah XVII, 9.5 It is my favourite text — Freud in nutshell. Tell her also to let me know when she can what is being discovered about Emotion. You know that in a week my brother goes to the country. I want you then, if you will, to take on the organizing of every other visit;6 also the following up of C.A’s advice7 or any other similar activities, in so far as seems necessary after my brother is gone and finished. Will you also be so very kind as to look after novels for me? Those you gave my brother last time have been a godsend. Could read a Geo. Birmingham,8 not Red Hand of Ulster, Search Party, or Lalage’s Lovers. Could you also get from Spectator Office (just by Waterloo Bridge) the number with review of my Mysticism?9, a About 4 or 5 weeks ago. Sorry to be such a bore about novels. I have grown terribly restless and find them an immense boon. [End] To Lady O. A thousand thanks for flowers which are the greatest delight. I have finished Ld. Granville’s letters,10 with much regret — Ly. B.11 is a most delightful woman — most lovable and able. The book gives a wonderful insight into the statesmen of the period — a wretched crew, except Fox.12 I wonder politics did not lead Ld. G. and Ly. B. to quarrel. So glad of P’s letter in Nation about S.S.13, 14 I admire S.S’s work very much indeed. The reviewer is a smug scoundrel — he must be very well off, over 50, and a member of several exceedingly comfortable Clubs. Who is the villain?15 Do you know? [End message]

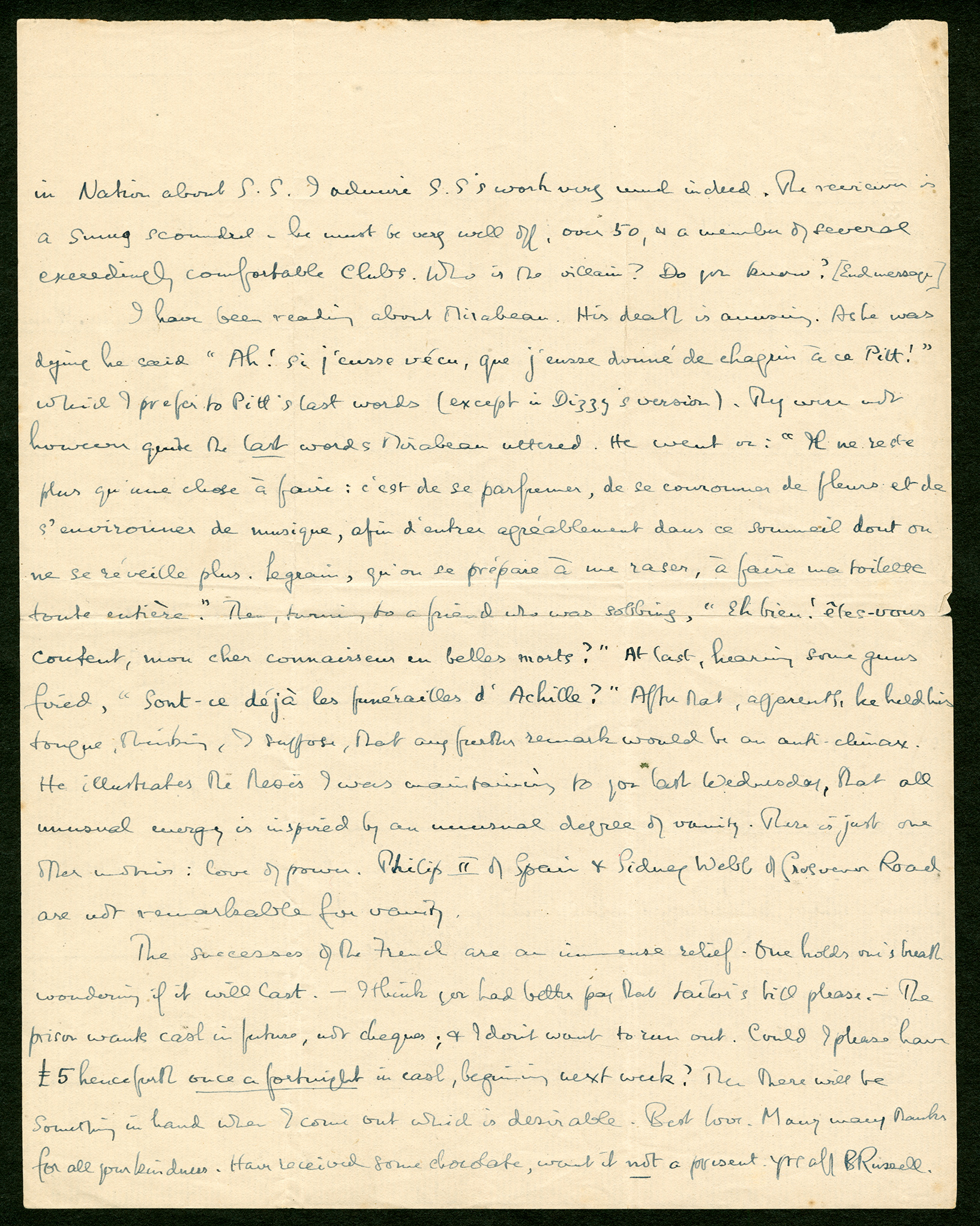

I have been reading about Mirabeau. His death is amusing.16 As he was dying he said “Ah! si j’eusse vécu, que j’eusse donné de chagrin à ce Pitt!”17 which I prefer to Pitt’s last words (except in Dizzy’s version).18 They were not however quite the last words Mirabeau uttered. He went on: “Il ne reste plus qu’une chose à faire: c’est de se parfumer, de se couronner de fleurs et de s’environner de musique, afin d’entrer agréablement dans ce sommeil dont on ne se réveille plus. Legrain, qu’on se prépare à me raser, à faire ma toilette toute entière.” Then, turning to a friend who was sobbing, “Eh bien! êtes-vous content, mon cher connaisseur en belles morts?” At last, hearing some guns fired, “Sont-ce déjà les funérailles d’Achille?”19 After that, apparently, he held his tongue, thinking, I suppose, that any further remark would be an anti-climax. He illustrates the thesis I was maintaining to you last Wednesday, that all unusual energy is inspired by an unusual degree of vanity. There is just one other motive: love of power. Philip II of Spain and Sidney Webb of Grosvenor Road are not remarkable for vanity.20

The successes of the French are an immense relief.21 One holds one’s breath wondering if it will last. — I think you had better pay that tailor’s bill please. — The prison wants cash in future, not cheques; and I don’t want to run out. Could I please have £5 henceforth once a fortnight in cash, beginning next week? Then there will be something in hand when I come out which is desirable. Best love. Many many thanks for all your kindness. Have received some chocolate, want it not a present.

Yrs aff

B Russell.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the signed, handwritten original in the Frank Russell papers in the Russell Archives. The letter covers both sides of a single sheet ruled on one side; it has three folds. The letter was an “official” one and approved by “HB”, the Brixton governor’s deputy.

- 2

your letter Dated 19 July 1918 (BRACERS 46927).

- 3

Miss King Frank Russell’s secretary. King had muddled the previous letter (BRACERS 46925) from the Russells (see Letter 41). BR was much vexed this time.

- 4

P’s remarks on Lytton Colette’s remarks about Lytton Strachey’s book, Eminent Victorians, were contained in a message from “Percy” in Frank’s letter to BR of 19 July 1918 (BRACERS 46927): “It is a great thing that Lytton has done in desentimentalising Miss Nightingale. — His picture of her is ever so faintly reminiscent of C.E.M. <Catherine Marshall> but with good judgment and something really terrific inside; just that indispensable volcanic quality which seems to me to be absolutely necessary to really great achievement. The way Lytton brings out the gradual demand for expression of Manning’s mean ambitious side is a triumph of subtle observation. One can hardly quarrel with the book’s deliberate showing up of the mesquin side of these characters when their other side has I suppose been universally proclaimed, nevertheless, it leaves one saturated with ungenerosity. When I was a child Gordon was my great hero and I still have a sneaking admiration for the twisted, knobbly, pigheaded adventure of the man.” In Letter 45 BR praised her directly for the remarks.

- 5

Please recommend to Miss Wrinch Jeremiah XVII, 9 “The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked: who can know it?” Wrinch and Raphael Demos were together exploring the nature of the emotions.

- 6

take on the organizing of every other visit Rinder would be responsible for deciding which trio of BR’s friends would visit him, making sure they would make a compatible group and would be available for a visit on the day selected. Presumably transportation to Brixton was also involved, along with informing visitors about the rules to be followed.

- 7

the following up of C.A’s advice BR was possibly recalling the “measures … agreed on with C.A. <Clifford Allen>” before his imprisonment, about how to avoid being called up after his release yet maintain the political and moral basis of his opposition to conscription (see Letter 24). The two men had debated the perplexities of this dilemma at the Marlow home of T.S. Eliot and his wife, over the weekend of 30 March–1 April 1918. Allen addressed the matter again in a reply to Letter 18, disagreeing with BR’s contention that abstaining from pacifist propaganda was an acceptable price for imprisoned C.O.s to pay for release. BR’s comment is jarring because, immediately after meeting Allen at the Eliots’, he had forcefully stated to Gilbert Murray (BRACERS 52367) that he would make no such pledge. But Allen could “entirely agree about evading arrest” through the pursuit of “useful work” (Letter 18), which for BR meant philosophy and in Allen’s case was the “labour work” for which he was “hoping against hope that I can get well” (27 June 1918, BRACERS 74282).

- 8

read a Geo. Birmingham George A. Birmingham was the pen name of prolific Irish novelist and Anglican cleric, James Owen Hannay (1865–1950).

- 9

Spectator … number with review of my Mysticism?BR had requested this issue of the weekly paper in his last two letters to Frank (Letters 34 and 41), before eventually obtaining it from Gladys Rinder (see Letter 53). The review, titled “Mysticism and Logic”, appeared in no. 4,695 (22 June 1918): 647–8. It had been brought to BR’s attention by Lucy Silcox (see BRACERS 80383). The anonymous reviewer, purportedly male, is identified in the marked copy of The Spectator as Mrs. C. Williams-Ellis, the former Amabel Strachey (1893–1984) and daughter of the Spectator’s editor, John St. Loe Strachey. Her brother was John Strachey. In 1915 she married the architect Major Clough Williams-Ellis, who soon began building Portmeirion, the Italianate village close to BR’s last home in North Wales. In 1960 he prefaced a sci-fi anthology edited by Amabel, Vol. 1 of Out of This World. It isn’t known, however, when they became friends, or whether BR ever knew she was the reviewer. For the review’s content and BR’s response of 30 July 1918, see Letter 53.

- 10

Ld. Granville’s letters Lord Granville, Private Correspondence, 1781–1821, 2 vols. (London: J. Murray, 1917).

- 11

Ly. B. Henrietta Frances, Lady Bessborough, née Spencer (1761–1821), mistress of the politician and diplomat Lord Granville (1773–1846), by whom she had two children.

- 12

except Fox Charles James Fox (1749–1806), aristocratic Whig leader and outspoken critic of the repressive measures enacted during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars by the administration of his arch-rival, William Pitt the Younger. As a proponent of parliamentary and other reforms, Fox was something of a mentor to the young Lord John Russell, who completed a laudatory three-volume life of his political hero, The Life and Times of Charles James Fox (1859–66).

- 13

P’s letter in Nation about S.S. Dated the same day as BR’s own letter of protest (Letter 39), Philip Morrell’s angry letter to the editor of The Nation (“Mr. Sassoon’s War Verses”, 23 [20 July 1918)]: 418–19) appeared two days before BR sent the present letter. Morrell called The Nation’s review of 13 July “pedantic”; the anonymous reviewer (J. Middleton Murry) should have put readers “into the mood to appreciate for themselves a moving and dramatic document.”

- 14

- 15

Who is the villain? BR soon learned from Ottoline (BRACERS 114750) that “the villain” (i.e., the hostile reviewer of Siegfried Sassoon’s Counter-Attack and Other Poems) was the critic J. Middleton Murry, husband of Katherine Mansfield, and none of the things BR supposed he was. See Letter 48, note 3.

- 16

reading about Mirabeau. His death is amusing. In Letter 48 BR told Ottoline that he was “absorbed in a 3-volume Mémoire” of Honoré-Gabriel Riqueti, Comte de Mirabeau (1749–1791), but the edition has not been identified. Mirabeau was an early and moderate leader of the French Revolution who favoured transforming the monarchy along British constitutional lines rather than republican democracy. He was president of the Jacobin Club and one of the foremost orators in the National Assembly, to whose deliberations he continued to contribute until shortly before his death from pericarditis, age 42.

- 17

“Ah! si j’eusse vécu... chagrin à ce Pitt!” [Translation:]“If I had lived, what grief I would have caused this Pitt!” The source is Lettres d’amour de Mirabeau, précédées d’une étude sur Mirabeau par Mario Proth (Paris: Garnier Frères, 1874), p. 52.

- 18

prefer to Pitt’s last words (except in Dizzy’s version) As William Pitt the Younger (1759–1806) lay dying, this unyielding foe of both revolutionary and Napoleonic France supposedly proclaimed, “O my country! How I love my country”. Yet in a story related to newly elected M.P. Benjamin Disraeli (1804–1881) by an elderly parliamentary servant, the late Conservative Prime Minister’s final words did not attest to his patriotism but, rather, to a simple craving for a mutton pie. See Lord Rosebery, Pitt (London: Greenwood, 1891, p. 258; “What Shall I Read?”, Papers 1: 361).

- 19

“Il ne reste plus … funérailles d’Achille?” [Translation:] “There is only one thing left to do: to be perfumed and garlanded and enveloped by music, so as to drift pleasantly into that sleep from which one never wakes” … “Legrain, who is preparing to shave me and wash my entire body” … “Well! Are you happy, my dear connoisseur of beautiful deaths?” … “Are these the funerals of Achilles already?” The source is Lettres d’amour de Mirabeau, précédées d’une étude sur Mirabeau par Mario Proth (Paris: Garnier Frères, 1874), p. 52.

- 20

Philip II … Sidney Webb … Grosvenor Road … vanity Famously lacking in vanity, Philip II (1527–1598, ruled from 1556) even refused to authorize an official chronicle of his reign, during which Spain extended its colonial empire and was embroiled in damaging European conflicts with France, England, and the Protestant Dutch. From the Pearsall Smiths’ London home at 44 Grosvenor Road, Westminster, BR had been a frequent guest of Sidney and Beatrice Webb at number 41. (BR returned to the area with Edith Russell in the early 1950s, keeping a pied-à-terre on the continuation of Grosvenor Road, called Millbank.) On first meeting her future husband, Beatrice noted that Sidney, a determined and infinitely patient champion of Fabian socialism, “has no vanity and is totally unself-conscious” (14 Feb. 1890; The Diary of Beatrice Webb. Vol. 1: 1873–92, “Glitter around and Darkness within”, ed. Norman and Jeanne Mackenzie [Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap P. of Harvard U. P., 1982], p. 324).

- 21

The successes of the Frenchare an immense relief. BR was referring to the early inroads made by the French-led Allied counter-attack in the second Battle of the Marne (15 July–6 Aug. 1918), which had commenced with Germany’s last major offensive on the Western Front. This assault on the French Fourth Army near Reims failed.

Textual Notes

- a

Mysticism Inserted.

Annotations by BR

In the late 1940s, when BR was going through his archives, and in the 1950s when he was revising his Autobiography, he would occasionally annotate letters. He did this to sixteen of the Brixton letters. Links to them are gathered here for convenient access to these new texts. In the annotations to the letters they are always followed by “(BR’s note.)”

Letter 2, note 5 happy.

5, note 6 congratulations to G.J.

9, note 28 bit of Girondin history.

12, note 6 friend.

15, note 2 (the letter in general).

20, note 7 G.J.

31, note 3 Dr’s treatment.

40, notes 9, 10 Ld. G.L.G, Lady B’s.

44, note 14 S.S.

48, note 48 Mother Julian’s Bird.

57, notes 13, 16 Ld. Granville’s to Ly. B., bless that Dr. … seat of intellect.

70, note 15 Mrs Scott.

73, note 12 E.S.P. Haynes.

76, note 4 Cave.

85, note 2 Marsh on Rupert.

102, notes 23, 28 Woolley, K. Lonsdale.

General Annotations

Brett note from Auto. 2: 93

Cousens note from Auto. 2: 71

Kyle note with her letters to BR

Rinder note from Auto. 2: 88n.

Silcox note on BRACERS 80365

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Catherine E. Marshall

Catherine E. Marshall (1880–1961), suffragist and internationalist who after August 1914 quickly moved from campaigning for women’s votes to protesting the war. An associate member of the No-Conscription Fellowship, she collaborated closely with BR during 1917 especially, when she was the organization’s Acting Hon. Secretary and he its Acting Chairman. Physically broken by a year of intense political work on behalf of the C.O. community, Marshall then spent several months convalescing with the NCF’s founding chairman, Clifford Allen, after he was released from prison on health grounds late in 1917. According to Jo Vellacott, Marshall was in love with Allen and “suffered deeply when he was imprisoned”. During his own imprisonment BR heard rumours that Marshall was to marry Allen (e.g., Letter 71), and Vellacott further suggests that the couple lived together during 1918 “in what seems to have been a trial marriage; Marshall was devastated when the relationship ended” (Oxford DNB). Throughout the inter-war period Marshall was active in the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

Clifford Allen

(Reginald) Clifford Allen (1889–1939; Baron Allen of Hurtwood, 1932) was a socialist politician and publicist who joined the Cambridge University Fabian Society while studying at Peterhouse College (1908–11). After graduating he became active in the Independent Labour Party in London and helped establish a short-lived labour newspaper, the Daily Citizen. During the war Allen was an inspiring and effective leader of the C.O. movement as chairman of the No-Conscription Fellowship, which he co-founded with Fenner Brockway in November 1914. Court-martialled and imprisoned three times after his claim for absolute exemption from war service was rejected, Allen became desperately ill during his last spell of incarceration. He was finally released from the second division of Winchester Prison on health grounds in December 1917, but not before contracting the tuberculosis with which he was finally diagnosed in September 1918. He was dogged by ill health for the rest of his life. BR had enormous affection and admiration for Allen (e.g., 68 in Papers 13, 46 in Papers 14), a trusted wartime political associate. From February 1919 until March 1920 he even shared Allen’s Battersea apartment. A close friendship was soured, however, by Allen’s rejection of BR’s unforgiving critique of the Bolshevik regime, which both men witnessed at first hand with the British Labour Delegation to Russia in May 1920 (see Papers 15: 507). Yet Allen was far from revolutionary himself and did not even identify with the left wing of the ILP (which he chaired in the early 1920s). He was elevated to the peerage as a supporter of Ramsay MacDonald’s National Government, an administration despised by virtually the entire labour movement. Although Allen’s old intimacy with BR was never restored after the Russia trip, any lingering estrangement did not inhibit him from enrolling his daughter, Joan Colette (“Polly”) at the Russells’ Beacon Hill School.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.

Dorothy Wrinch

Dorothy Maud Wrinch (1894–1976), mathematician, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. She studied mathematics and philosophy at Girton College, Cambridge, and came under BR’s influence in her second year when she took his course on mathematical logic. She taught mathematics at University College, London, 1918–21, and then at Oxford, 1922–30. Her first publications were in mathematical logic and philosophy, and during the 1920s she wrote on the philosophy of science. But in the 1930s her interests turned to mathematical biology and crystallography, and in 1935 she moved to the United States on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship and remained there for the rest of her life. Unfortunately, as a biologist she is best known for a long and stubborn controversy with Linus Pauling about the structure of proteins in which he was right and she was wrong. See Marjorie Senechal, I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science (New York: Oxford U. P., 2013). Chapter 7 is devoted to Wrinch’s interactions with BR in Brixton.

Edith Russell

Edith Russell (1900–1978) was an American biographer and part-time academic at Bryn Mawr College with whom BR became acquainted through his American friend Lucy Donnelly. She was the author of Wilfred Scawen Blunt (1938) and Carey Thomas of Bryn Mawr (1947). The former Edith Bronson Finch became BR’s fourth wife in 1952. She was a director of the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation.

Elizabeth Russell

Elizabeth Russell, born Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941), was a novelist who in 1891 married Graf von Arnim-Schlagenthin. She became known as “Elizabeth”, the name she used in publishing Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898), and she remained widely known as Elizabeth von Arnim, although the Library of Congress catalogues her as Mary Annette (Beauchamp), Countess von Arnim. She was a widow when she married BR’s brother, Frank, on 11 February 1916. The marriage was quickly in difficulty; she left it for good in March 1919, but they were never divorced and she remained Countess Russell (becoming Dowager Countess after Frank’s death in 1931).

George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

George Allen & Unwin Ltd., founded by Stanley Unwin in 1914, was BR’s chief British publisher, had published Principles of Social Reconstruction in 1916, and was in the process of publishing Roads to Freedom (1918) while BR was in Brixton.

Gilbert Murray

Gilbert Murray (1866–1957), distinguished classical scholar and dedicated liberal internationalist. He was Regius Professor of Greek at Oxford, 1908–36, and chair of the League of Nations Union, 1923–36. He and BR enjoyed a long and close friendship that was ruptured temporarily by bitter disagreement over the First World War. After Murray published The Foreign Policy of Sir Edward Grey, 1906–1915, in defence of Britain’s pre-war diplomacy, BR responded with a detailed critique, The Policy of the Entente, 1904–1914: a Reply to Professor Gilbert Murray (37 in Papers 13). Yet Murray still took the lead in campaigning to get BR’s sentence reassigned from the second to the first division and (later) in leading an appeal for professional and financial backing of an academic appointment for BR upon his release (the “fellowship plan”, which looms large in his prison correspondence). BR was still thankful for Murray’s exertions some 40 years later. See his portrait of Murray, “A Fifty-Six Year Friendship”, in Murray, An Unfinished Autobiography with Contributions by His Friends, ed. Jean Smith and Arnold Toynbee (London: Allen & Unwin, 1960).

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Governor of Brixton Prison / Carleton Haynes

Captain Carleton Haynes (1858–1945), the Governor of Brixton Prison in 1918, was a retired army officer and a cousin of BR’s acquaintance, the radical lawyer and author E.S.P. Haynes. In March 1919 BR sent Haynes, in jest, a copy (now in the Russell Archives) of his newly published Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy — so that the governor’s collection of works written by inmates while under his charge would “not ... be incomplete” (BRACERS 123167).

J. Middleton Murry

J. Middleton Murry (1889–1957), critic and editor, was educated in classics at Brasenose College, Oxford, before establishing in 1911 the short-lived avant-garde journal, Rhythm. In May 1918 he married the author Katherine Mansfield, to whose literary legacy he became devoted after her death from tuberculosis only five years later. The couple were frequent visitors to Garsington Manor, and Murry appears at one time to have had a romantic yearning for Ottoline (see note to Letter 48). Although Murry’s scornful treatment of Sassoon’s poetry annoyed BR (see Letter 39), he became, nevertheless, a frequent contributor to The Athenaeum during Murry’s two-year stint as its editor (1919–21). After the ailing literary weekly merged with The Nation in 1921, Murry continued his vigorous promotion of modernism in the arts from the helm of his own monthly journal, The Adelphi, which he edited for 25 years. During the First World War he worked as a translator for the War Office but became an uncompromising pacifist in the 1930s. One of the last assignments of his journalistic career was as editor of the pacifist weekly, Peace News (1940–46). Source: Oxford DNB.

Katherine Mansfield

Katherine Mansfield (1888–1923), pseudonym of Kathleen Mansfield Beauchamp, New Zealand-born short-story writer. After studying music in her native country, Mansfield moved to London in 1908, married George Bowden, a music teacher, whom she left after a few days, the marriage unconsummated. She was at the time pregnant from a previous affair. Her experiences in Bavaria, where the child was stillborn, became the background for her first collection of stories, In a German Pension (1911), most of which had been previously published in A.R. Orage’s journal, The New Age. In 1911 she met J. Middleton Murry, who fell quickly under her spell and with whom she was to be associated until the end of her life, though they frequently lived independently and married only in 1918. Her health had long been fragile, and in 1918 she was diagnosed with the tuberculosis which eventually killed her. BR met her in 1916 when she was living in Gower Street, near BR’s brother’s house in Gordon Square. For a short time they had an intimate friendship, but not an affair. BR found her talk, especially about what she planned to write, “marvellous, much better than her writing”. But “when she spoke about people she was envious, dark and full of alarming penetration in discovering what they least wished known.” She spoke in this vein of Ottoline Morrell. BR listened but in the end “believed very little of it” and, after that, saw Mansfield no more (Auto. 2: 27). Main biography: Antony Alpers, The Life of Katherine Mansfield (New York: Viking, 1980).

Lytton Strachey

Lytton Strachey (1880–1932), biographer, reviewer and a quintessential literary figure of the Bloomsbury Group. He is best known for his debunking portraits of Cardinal Manning, Florence Nightingale, Dr. Arnold and General Gordon, published together as Eminent Victorians (London: Chatto & Windus, 1918; Russell’s library), which BR read in Brixton with great amusement as well as some critical reservations (see Letter 7). Although Strachey was homosexual, he and the artist Dora Carrington were devoted to each other and from 1917 lived together in Tidmarsh, Berkshire. BR had become acquainted with the somewhat eccentric Strachey, a fellow Cambridge Apostle, while his slightly younger contemporary was reading history at Trinity College. He admired Strachey’s literary gifts, but doubted his intellectual honesty. Almost three decades later BR fleshed out the unflattering thumbnail of Strachey drawn for Ottoline in Letter 7, in a “Portrait from Memory” for BBC radio. Strachey was “indifferent to historical truth”, BR alleged in that broadcast, “and would always touch up the picture to make the lights and shades more glaring and the folly or wickedness of famous people more obvious” (The Listener 48 [17 July 1952]: 98). Main biography: Michael Holroyd, Lytton Strachey: a Critical Biography, 2 vols. (London: Heinemann, 1967–68).

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

Philip Morrell

Philip Morrell, Ottoline’s husband (1870–1943), whom she had married in 1902 and with whom, four years later, she had twins — Julian, and her brother, Hugh, who died in infancy. The Morrells were wealthy Oxfordshire brewers, although Philip’s father was a solicitor. He won the Oxfordshire seat of Henley for the Liberal Party in 1906 but held this Conservative stronghold only until the next general election, four years later. For the second general election of 1910 he ran successfully for the Liberals in the Lancashire manufacturing town of Burnley. But Morrell’s unpopular anti-war views later cost him the backing of the local Liberal Association, and his failure to regain the party’s nomination for the post-war election of 1918 (see Letter 89) effectively ended his short political career. Unlike many other Liberal critics of British war policy (including BR), Morrell did not transfer his political allegiance to the Labour Party. Although Ottoline and her husband generally tolerated each other’s extra-marital affairs, a family crisis ensued when in 1917 Philip impregnated both his wife’s maid and his secretary (see Letter 48).

Prohibited areas

On 17 July 1918 (BRACERS 75814) General George Cockerill, Director of Special Intelligence at the War Office, notified Frank Russell that constraints on BR’s freedom of movement, imposed almost two years before, had been lifted as of 11 July. Since 1 September 1916, BR had been banned under Defence of the Realm Regulation 14 from visiting any of Britain’s “prohibited areas” without the express permission of a “competent military authority”. The extra-judicial action was taken partly in lieu of prosecuting BR for a second time under the Defence of the Realm Act, on this occasion over an anti-war speech delivered in Cardiff on 6 July 1916 (63 in Papers 13). (Britain’s Director of Public Prosecutions was confident that a conviction could be secured but concerned lest BR should again exploit the trial proceedings for propaganda effect and thereby create “a remedy … worse than the disease” [HO 45/11012/314760/6, National Archives, UK].) Since the exclusion zone covered many centres of war production, BR would be prevented (according to the head of MI5) from spreading “his vicious tenets amongst dockers, miners and transport workers” (quoted in Papers 13: lxiv). But the order also applied to military and naval installations and almost the entire coastline. As a lover of the sea and the seaside, BR chafed under the latter restriction: “I can’t tell you how I long for the SEA”, he told Colette (Letter 75).

Raphael Demos

Raphael Demos (1892–1968), one of BR’s logic students in the autumn of 1916. Then on a Sheldon travelling fellowship, Demos eventually returned to Harvard where he taught philosophy for the rest of his career. Russell had taught him at Harvard in 1914 and described him in his Autobiography (1: 212). In 1916–17 BR recommended two of his articles to G.F. Stout, the editor of Mind (“A Discussion of a Certain Type of Negative Proposition”, Mind 26 [Jan. 1917]: 188–96; and “A Discussion of Modal Propositions and Propositions of Practice”, 27 [Jan. 1918]: 77–85); see BRACERS 54831 and 2962 (and for Demos’s letters to BR in 1917 about the submissions, BRACERS 76495 and 76496, and BR’s reply to the first, BRACERS 838).

Siegfried Sassoon

Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967), soldier awarded the MC and anti-war poet. Ottoline had befriended him in 1916, and the following year, when Sassoon refused to return to his regiment after being wounded, she and BR helped publicize this protest, which probably saved him from a court martial. BR even assisted Sassoon in revising his famous anti-war statement, which was read to the House of Commons by a Liberal M.P. on 30 July 1917. Sassoon’s actions were an embarrassment to the authorities, for he was well known as both a poet and a war hero. Unable to hush the case up, the government acted with unexpected subtlety and declared Sassoon to be suffering from shell-shock and sent him to Craiglockhart War Hospital for Officers, near Edinburgh. After a period of recuperation in Scotland overseen by military psychiatrist Capt. W.H.R. Rivers, Sassoon decided to return to the Front (see Jean Moorcroft Wilson, Siegfried Sassoon: Soldier, Poet, Lover, Friend [New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2014]). He was again wounded in July 1918 and was convalescing in Britain during some of BR’s imprisonment. Although each admired the other’s stand on the war, BR and Sassoon were never close in later years. Yet Sassoon did pledge £50 to the fellowship plan fund (see BRACERS 114758), and decades later he donated a manuscript in support of BR’s International War Crimes Tribunal (see BRACERS 79066).

Stanley Unwin

Stanley Unwin (1884–1968; knighted in 1946) became, in the course of a long business career, an influential figure in British publishing and, indeed, the book trade globally — for which he lobbied persistently for the removal of fiscal and bureaucratic impediments to the sale of printed matter (see his The Truth about a Publisher: an Autobiographical Record [London: Allen & Unwin, 1960], pp. 294–304). In 1916 Principles of Social Reconstruction became the first of many BR titles to appear under the imprint of Allen & Unwin, with which his name as an author is most closely associated. Along with G.D.H. Cole, R.H. Tawney and Harold Laski, BR was notable among several writers of the Left on the publishing house’s increasingly impressive list of authors. Unwin himself was a committed pacifist who conscientiously objected to the First World War but chose to serve as a nurse in a Voluntary Aid Detachment. With occasional departures, BR remained with the company for the rest of his life (and posthumously), while Unwin also acted for him as literary agent with book publishers in most overseas markets.

T.S. Eliot

The poet and critic Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888–1965) was a student of BR’s at Harvard in 1914. BR had sensed his ability, especially “a certain exquisiteness of appreciation” (to Lucy Donnelly, 11 May 1914; SLBR 1: 491), but did not see a genius in embryo. After Eliot travelled to England later the same year, to study philosophy at Oxford under H.H. Joachim, BR became something of a father figure to the younger man. He also befriended Eliot’s (English) wife, Vivienne, whom he had hastily married in 1915 and with whom BR may have had an affair the following year. BR shared his Bloomsbury apartment (at 34 Russell Chambers) with the couple for more than a year after their marriage, and jointly rented a property with them in Marlow, Bucks. (see Letter 78). He further eased Eliot’s monetary concerns by arranging paid reviewing for him and giving him £3,000 in debentures from which BR was reluctant, on pacifist grounds, to collect the income (Auto. 2: 19). Eliot’s financial security was much improved by obtaining a position at Lloyd’s Bank in 1917, but during BR’s imprisonment he faced uncertainty of a different kind as the shadow of conscription loomed over him (see, e.g., Letter 27). Nine years after the war ended Eliot returned the securities (BRACERS 76480).

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).