Brixton Letter 43

BR to Constance Malleson

July 21, 1918

- AL

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-43

BRACERS 19322

<Brixton Prison>1

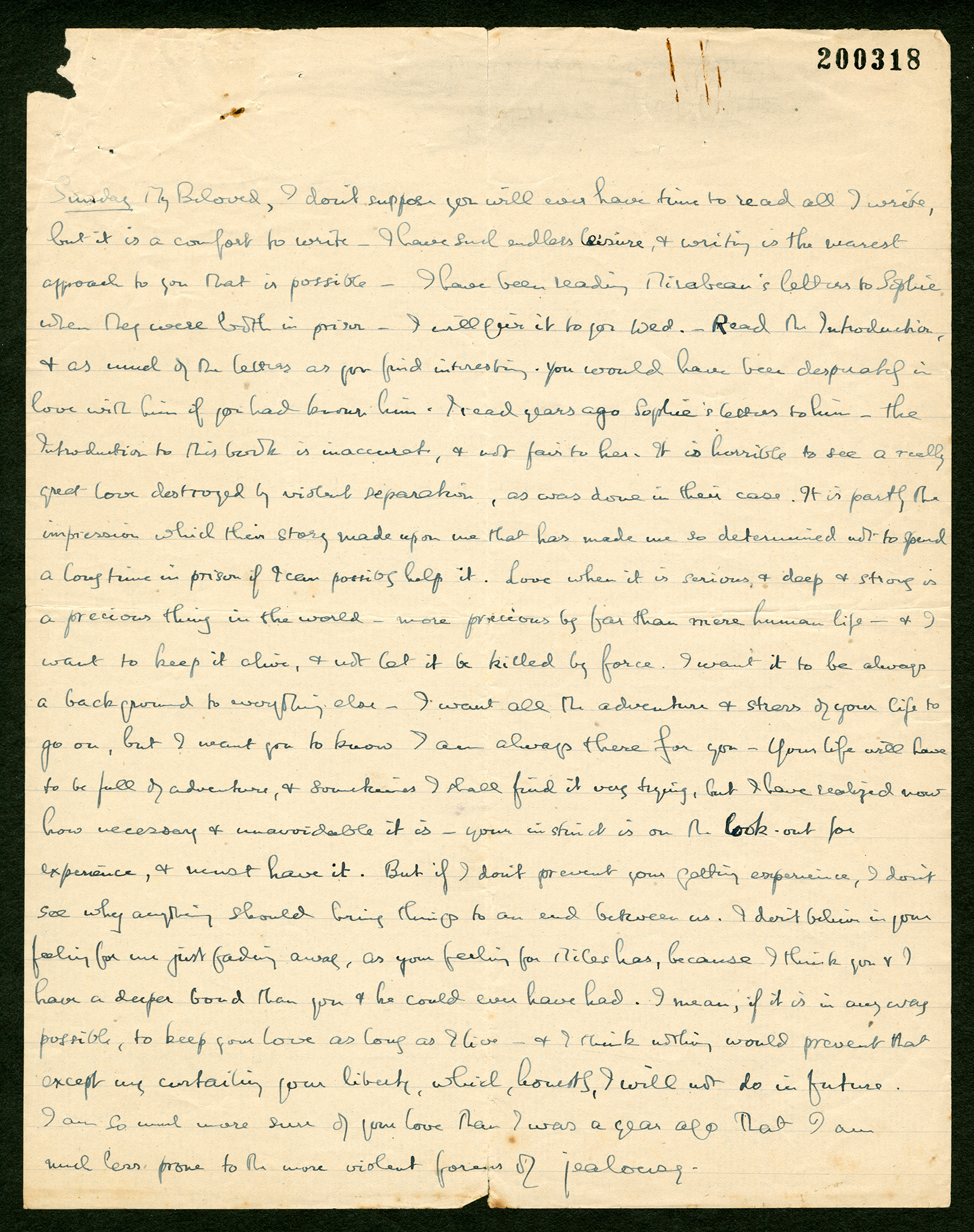

Sunday2

My Beloved,

I don’t suppose you will ever have time to read all I write, but it is a comfort to write. I have such endless leisure, and writing is the nearest approach to you that is possible. I have been reading Mirabeau’s letters to Sophie when they were both in prison.3 I will give it to you Wed. — Read the Introduction, and as much of the letters as you find interesting. You would have been desperately in love with him if you had known him. I read years ago Sophie’s letters to him4 — the Introduction to this book is inaccurate, and not fair to her. It is horrible to see a really great love destroyed by violent separation, as was done in their case. It is partly the impression which their story made upon me that has made me so determined not to spend a long time in prison if I can possibly help it. Love when it is serious and deep and strong is a precious thing in the world — more precious by far than mere human life — and I want to keep it alive, and not let it be killed by force. I want it to be always a background to everything else. I want all the adventure and stress of your life to go on, but I want you to know I am always there for you. Your life will have to be full of adventure, and sometimes I shall find it very trying, but I have realized now how necessary and unavoidable it is — your instinct is on the look-out for experience, and must have it. But if I don’t prevent your getting experience, I don’t see why anything should bring things to an end between us. I don’t believe in your feeling for me just fading away, as your feeling for Miles has, because I think you and I have a deeper bond than you and he could ever have had. I mean, if it is in any way possible, to keep your love as long as I live — and I think nothing would prevent that except my curtailing your liberty, which, honestly, I will not do in future. I am so much more sure of your love than I was a year ago that I am much less prone to the more violent forms of jealousy.5

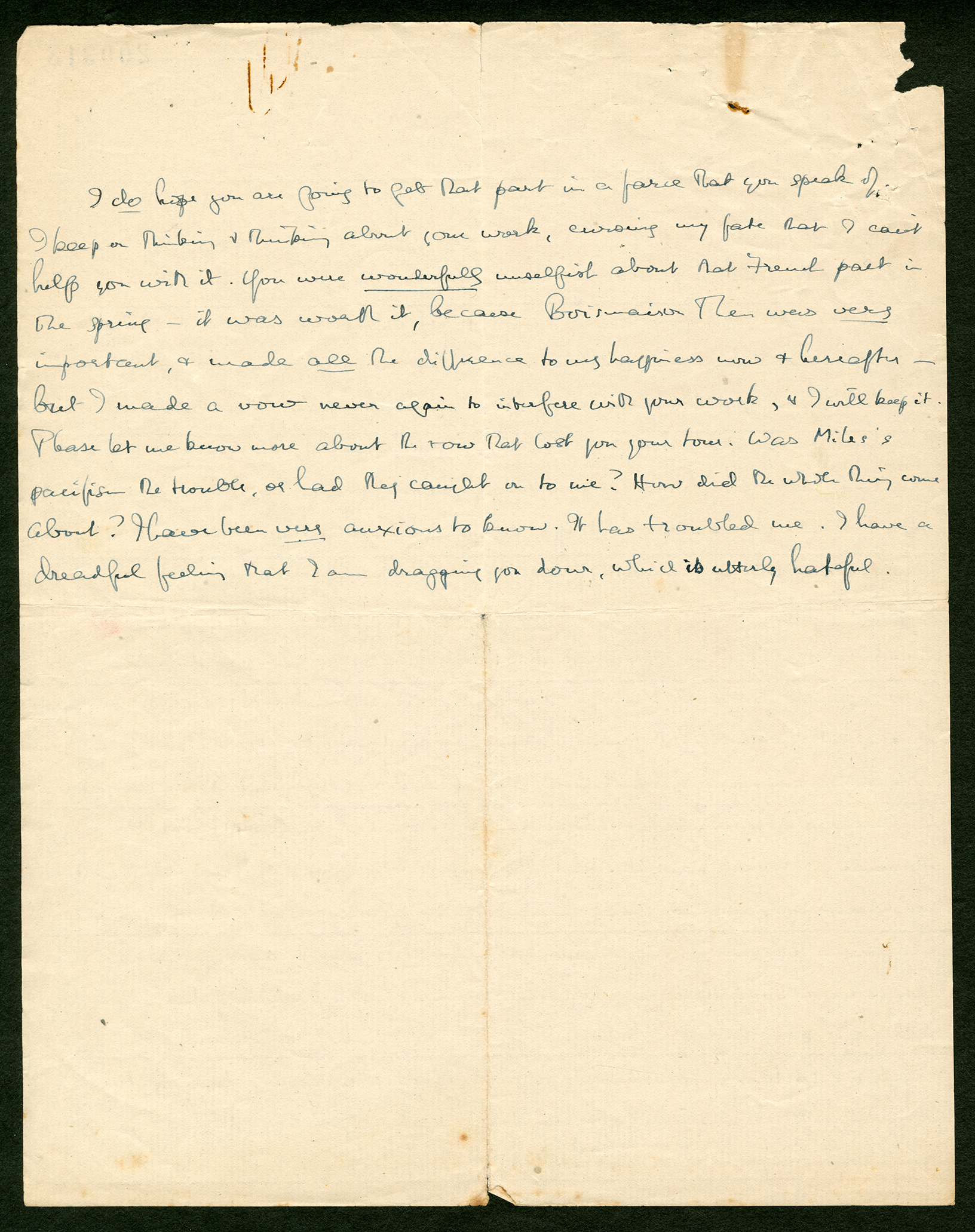

I do hope you are going to get that part in a farce that you speak of.6 I keep on thinking and thinking about your work, cursing my fate7 that I can’t help you with it. You were wonderfully unselfish about that French part in the spring8 — it was worth it, because Boismaison then was very important, and made all the difference to my happiness now and hereafter — but I made a vow never again to interfere with your work, and I will keep it. Please let me know more about the row that lost you your tour.9 Was Miles’s pacifism the trouble, or had they caught on to me? How did the whole thing come about? I have been very anxious to know. It has troubled me. I have a dreadful feeling that I am dragging you down, which is utterly hateful.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the unsigned, handwritten original in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. It is written on both sides but only half-way down the verso of the sheet of thin, laid paper, ruled on one side and folded twice, so that there was no writing on either exposed quarter of the sheet.

- 2

[date] Colette’s note clipped to the letter reads: “This might be Sunday 21st July 1918. CM”.

- 3

reading Mirabeau’s letters to Sophie when they were both in prison BR had already, very early in June 1918, written ColetteLetter 11 disguised as one from Mirabeau to Sophie de Monier (sic). The letters of the French revolutionary statesman, the Comte de Mirabeau (1749–1791), written when he was imprisoned in the castle at Vincennes, were first published in 1793. “Sophie” was the name he used for Marie Thérèse de Monnier (1754–1789) during their illicit affair. An edition is Benjamin Gastineau, Les Amours de Mirabeau et de Sophiede Monnier, suivis des lettres choisies de Mirabeau à Sophie, de lettres inédites de Sophie, et du testament de Mirabeau par Jules Janin (Paris: Chez tous les libraires, 1865). BR wrote to others about Mirabeau at this time: to Frank he wrote on 22 July 1918 (Letter 44) about Mirabeau’s death; in Letter 48 he wrote Ottoline that he was reading an unidentified three-volume Mémoire of Mirabeau.

- 4

I read years ago Sophie’s letters to him A selection of her letters was published in Paul Cottin, ed., Sophie et Mirabeau d’après leur correspondance secrète inédite (Paris: Plon-Nourrit, 1903). Cottin published more letters in the journal La nouvelle revue rétrospective, Paris, in 1903–04.

- 5

more violent forms of jealousy In 1917 BR was very jealous of Colette’s relationship with her director, Maurice Elvey. BR wrote her on 24 September (BRACERS 19218) that it had “robbed me of sleep, and when I don’t sleep I cease to be quite sane.” The following day he wrote a savage assessment of her character, “What She Is and What She Might Become” (RA2 710.201999). He called her vain, crude, commercial and destitute of self-control. Presumably the episode was what BR had in mind when writing in this letter of his proneness to “the more violent forms of jealousy”, rather than physical violence, of which abuse there is no hint anywhere in their correspondence.

- 6

get that part in a farce that you speak of On 21 June Colette sent a message (in Rinder’s letter to BR, BRACERS 79616) that she had two or three jobs under consideration. The title of the farce she mentioned is unknown. Then, in July, she noted that an American, Colonel J. Mitchell, whom she met at a luncheon party hosted by her mother at Claridges on 17 July, told her that an underling of his had done her out of a job (BRACERS 113143). On 3 August (BRACERS 113147), she wrote: “I am going to be very poor until at least the spring.”

- 7

cursing my fate Shakespeare’s famous Sonnet 29 has a line, “And look upon myself, and curse my fate” (“All the Poems We Have Most Enjoyed Together”: Bertrand Russell’s Commonplace Book, ed. K. Blackwell [Hamilton, ON: McMaster U. Library P., 2018], p. 64; the “we” being Ottoline and BR).

- 8

that French part in the springColette had given up a part in Eugene Brieux’s play Blanchette in order to go to Ashford with BR.

- 9

the row that lost you your tour In her letter of 26 July (BRACERS 113145), Colette explained it as follows: “Miles had seen a great deal of Marie <Blanche> at her theatre; and her manager — that same infernal big-wig — dislikes Miles and his politics; and my politics, of course, too. So his general displeasure got vented on me, as he’d not wish to vent it on Marie, and couldn’t vent it on Miles. Of course you didn’t come into it at all.”

Boismaison

Colette and BR vacationed at a house, The Avenue, owned by Mrs. Agnes Woodhouse and her husband, in the countryside near Ashford Carbonel, Shropshire, in August 1917. They nicknamed the house “Boismaison”. Agnes Woodhouse took in paying guests. Their first visit was idyllic. They returned for other vacations — in 1918 before he entered prison and in April 1919. Their plan to go soon after he got out of prison failed because their relationship faltered for a time. They discussed returning in the summer of 1919 — a booking was even made for 12–19 July — but in the end they didn’t go. See S. Turcon, “Then and Now: Bertie and Colette’s Escapes to the Peak District and Welsh Borderlands”, Russell 34 (2014): 117–30.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).

Marie Blanche

Marie Blanche (1891–1973) studied at the Academy of Dramatic Arts where she met Colette. She sang as well as acted and had a successful career on the London stage in the 1920s. A photograph of her appeared in The Times, 20 March 1923, p. 16.

Maurice Elvey

Maurice Elvey (1887–1967) was a prolific film director (of silent pictures especially) and enjoyed a very successful career in that industry lasting many decades. Born William Seward Folkard into a working-class family, Elvey changed his name around 1910, when he was acting. He directed his first film, The Fallen Idol, in 1913. By 1917, when he directed Colette in Hindle Wakes, he had married for a second time — to a sculptor, Florence Hill Clarke — his first marriage having ended in divorce. Elvey and Colette had an affair during the filming of Hindle Wakes, beginning in September 1917, which caused BR great anguish. In addition to his feeling of jealousy during his imprisonment, BR was worried over the rumour that Elvey was carrying a dangerous sexually transmitted disease. (See BR, “My First Fifty Years”, RA1 210.007050–fos. 127b, 128, and Monk, 2: 507). Colette later maintained that Elvey cleared himself (“Letters to Bertrand Russell from Constance Malleson, 1916–1969”, p. 154, typescript, RA). BR removed the allegation from the Autobiography as published (see 2: 37), but he remained fearful. After Elvey’s long-lost wartime film about the life of Lloyd George was rediscovered and restored in the 1990s, it premiered to considerable acclaim (see Letter 87, note 12).

Miles Malleson

Miles Malleson (1888–1969), actor and playwright, was born in Croydon, Surrey, the son of Edmund and Myrrha Malleson. He married his first wife, a fellow actor, Lady Constance Annesley (stage name, Colette O’Niel), in 1915. They had met at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts). Their marriage was an “open” one. In 1914 Miles enlisted in the City of London Fusiliers and was sent to Malta. He became ill and was discharged, unfit for further service. He became active in the No-Conscription Fellowship and wrote anti-war stage plays as well as a pamphlet, Cranks and Commonsense (1916). In the 1930s he began to write for the screen and act in films, in which he became a very well-known character actor, as well as continuing his stage career at the Old Vic in London. He married three times: his second marriage was to Joan Billson, a physician (married 1923, divorced 1940), with whom he had two children; his third wife was Tatiana Lieven, an actress (married 1946). He died in London in March 1969.

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

Priscilla, Lady Annesley

Priscilla, Lady Annesley (1870–1941), second wife of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl of Annesley (1831–1908) and mother of Lady Constance Malleson. Colette described her mother as “among the most beautiful women of her day” with a love of bright colours and walking (After Ten Years [London: Cape, 1931], pp. 12–14).

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.