Brixton Letter 29

BR to Constance Malleson

June 27, 1918

- AL

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-29

Russell 30 (2010): 114–15

BRACERS 19317

<Brixton Prison>1

Thursday2

All the letters I have ever had were less wonderful than this one, my Heart’s Comrade, my Beloved. I could not have imagined any letter3 that would so light up my prison cell, and so fill my heart with <burn hole in sheet>pa of joy. I bless you every hour. I do love you to think of me as you <burn hole in sheet>.b I feel so much that way — such a longing to creep into your arms and be at peace. Your arms are so strong and loving and bring such warmth into the depths of my being — I have the most vivid imagining of them and of the touch of your lips. O my dear dear Love, the joy that is before us — I dare not think of it. If you are not in work when I come out we must go to Boismaison. I was afraid you were nervous of letters, from something you said a fortnight ago, so I wrote in a very subdued style4 — and your letter was all the greater joy. As soon as I am safe from being called up, we will give up all attempts at concealment, don’t you think so? — I am sorry for Marie5 — it must have been dreadful for her. Gladys’s letter came this morning, with lovely things from you.6 I always thought Chatsauvage had some likeness to Prince André.7 Did you like Natacha?8 — Miss R. gives news that Miss Wrinch is unhappy9 — I wonder if you could make friends with her, through Miss R? I think she is at No. 10, your square.10 I feel she might like it. — I spend endless time here in day-dreams — not impossible ones — of wonderful things we will do together. We have never been by the sea together. After the war there will be abroad. Some day there will be a country cottage. Quite soon, I hope, there will be Bury Street. — “A heavy burning iron”11 you say — mostly my doing — it is quite wonderful that your love survived that time. It is that that makes me so very very happy now — it makes me feel peace with you. My soul’s joy, I think of you with love and tenderness every moment, and I see the future as a shining joy. I love you with my mind and sober judgment just as much as with my passion — in yourself, as much as in what you are for me. For me you are just the whole difference between life and despair — you give me happiness and gentleness — and through them, the strength one needs for the world at this time. Our future shall be full of greatness as well as joy — what you give me shall be given to the world. Goodbye Beloved. I kiss your eyes and stroke your hair. I want to lay my face against your cheek and feel your arms enfolding me. Goodbye Goodbye my lovely Dear, my Darling.

- 1

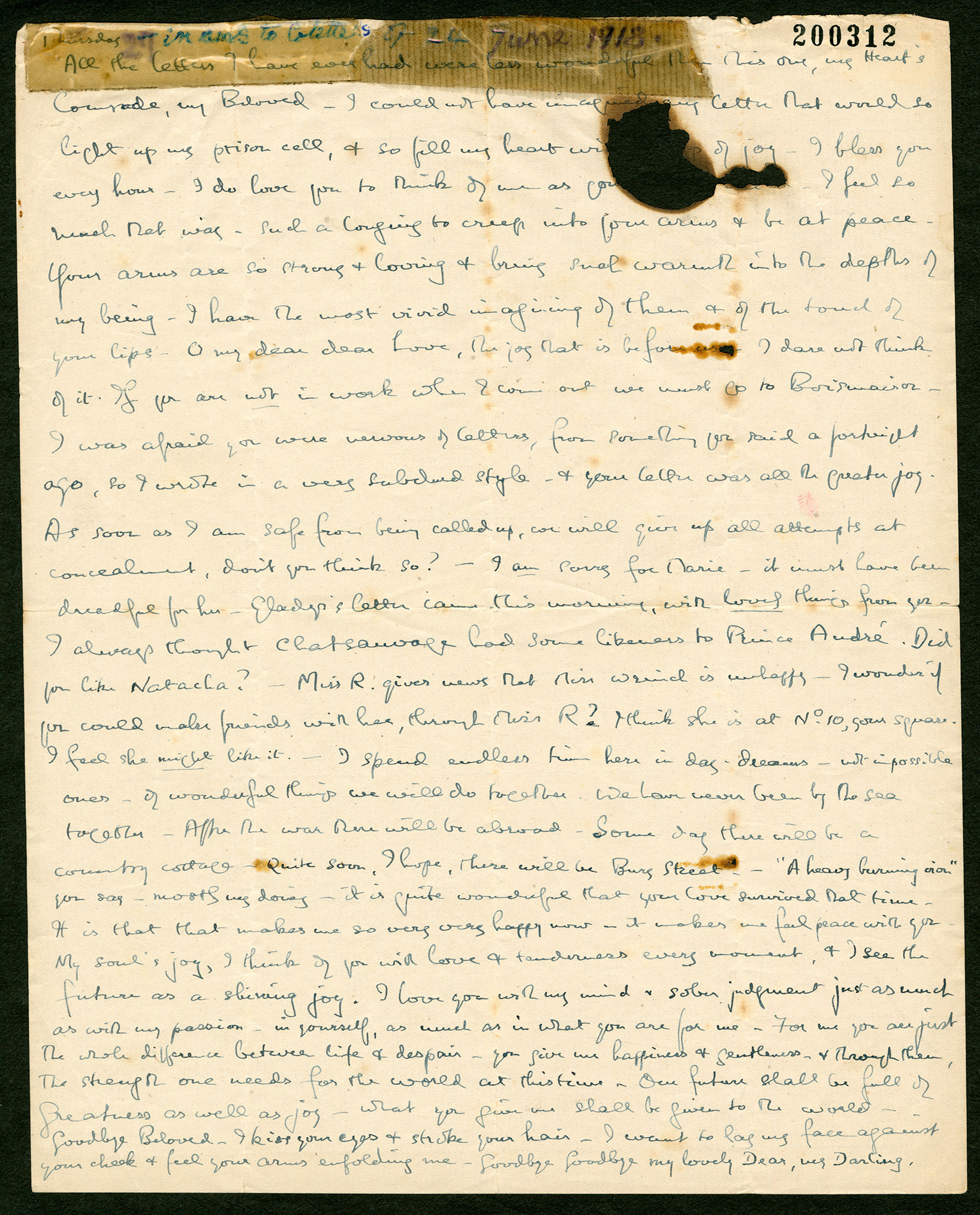

[document] The letter was edited from the unsigned, single-sheet original in BR’s hand in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. An image of the letter illustrated an annotated edition of the text in S. Turcon, “Like a Shattered Vase: Russell’s 1918 Prison Letters”, Russell 30 (2010): 101–25.

- 2

[date] “<I>n ans<wer> to Colette’s of 24 June 1918” (BRACERS 113135); added by Colette.

- 3

imagined any letter This is probably the first of Colette’s smuggled letters, since she wrote on 24 June: “it is absolutely wonderful that the abomination of those official letters is over and done with” (BRACERS 113135).

- 4

I wrote in a very subdued style His letters following Letter 17, namely 24, 25 and 26, were indeed subdued in comparison with those immediately before and after.

- 5

sorry for Marie In her letter of 24 June, Colette wrote: “Marie got ill and was quite without £sd … Marie is now well again.” This is a veiled version of Marie’s troubles. In Letter 22, editorially dated 18 June 1918, BR asked if the child Marie was going to have was Miles’s.

- 6

Gladys’s letter … things from you A letter from Gladys Rinder, 21 June 1918 (BRACERS 79616), contained messages from Colette in her personas of “C.O.’N.” and “G.J.” The first message noted that Lady Constance (i.e., Colette) would visit BR on the following Wednesday (i.e., 26 June).

- 7

Chatsauvage ... Prince André BR was referring to himself, one of Colette’s nicknames for him being “Chatsauvage” (“wildcat”). Prince André (Andrei Bolkonsky) is a character in Tolstoy’s War and Peace. Colette had written as G.J. in Gladys Rinder’s letter of 21 June 1918 that she had “been thinking a good deal about our friend Monsieur Chatsauvage and his new book. He reminds me continually of Tolstoy’s Prince Andrei, and also of Count Bezukov.” Pierre Bezukhov is another character in the novel.

- 8

Natacha Natasha Rostova, the young heroine of Tolstoy’s War and Peace.

- 9

Miss R … Miss Wrinch is unhappy Referring to the affair she had started with another of BR’s students, Raphael Demos, Wrinch reported to BR via Rinder that she had “taken your advice and embarked on an adventure but it isn’t turning out at all successfully” (21 June 1918, BRACERS 79616). By mid-July, however, Rinder assured BR that, however unhappy Wrinch may have been previously, “Dorothy is having a gay time”. Yet her personal life was becoming, if anything, even more complicated, for Demos, according to Rinder, “is not the only string” (BRACERS 79623).

- 10

your square Mecklenburgh Square, London WC1.

- 11

“A heavy burning iron” In her letter of 24 June Colette had written: “Some kind of heavy burning iron has passed over me this year” (BRACERS 113135).

Textual Notes

- a

with <...>p The letter has a hole in the paper (from a cigarette burn) where a word or words had been written; “songs” appears in both typed versions by Colette, but that cannot be what is missing before the visible “p” after the burn. Perhaps it is “a leap”.

- b

me as you<…> Words are missing from the letter because of a hole made by a cigarette burn. Already gone, they were not transcribed in the typed versions.

Boismaison

Colette and BR vacationed at a house, The Avenue, owned by Mrs. Agnes Woodhouse and her husband, in the countryside near Ashford Carbonel, Shropshire, in August 1917. They nicknamed the house “Boismaison”. Agnes Woodhouse took in paying guests. Their first visit was idyllic. They returned for other vacations — in 1918 before he entered prison and in April 1919. Their plan to go soon after he got out of prison failed because their relationship faltered for a time. They discussed returning in the summer of 1919 — a booking was even made for 12–19 July — but in the end they didn’t go. See S. Turcon, “Then and Now: Bertie and Colette’s Escapes to the Peak District and Welsh Borderlands”, Russell 34 (2014): 117–30.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Dorothy Wrinch

Dorothy Maud Wrinch (1894–1976), mathematician, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. She studied mathematics and philosophy at Girton College, Cambridge, and came under BR’s influence in her second year when she took his course on mathematical logic. She taught mathematics at University College, London, 1918–21, and then at Oxford, 1922–30. Her first publications were in mathematical logic and philosophy, and during the 1920s she wrote on the philosophy of science. But in the 1930s her interests turned to mathematical biology and crystallography, and in 1935 she moved to the United States on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship and remained there for the rest of her life. Unfortunately, as a biologist she is best known for a long and stubborn controversy with Linus Pauling about the structure of proteins in which he was right and she was wrong. See Marjorie Senechal, I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science (New York: Oxford U. P., 2013). Chapter 7 is devoted to Wrinch’s interactions with BR in Brixton.

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Heart’s Comrade

Colette first called BR her “heart’s comrade” in her letter of 17 November 1916 (BRACERS 112964). On 9 December (BRACERS 112977), she explained: “I want you as comrade as well as lover.” On 9 April 1917 (BRACERS 19145), he reciprocated the sentiment for the first time. In a letter of 1 January 1918 (BRACERS 19260), BR was so upset with her that he could no longer call her “heart’s comrade”. After their relationship was patched up, he wrote on 16 February 1918 (BRACERS 19290): “I do really feel you now again my Heart’s Comrade.” The last time that BR expressed the sentiment in a letter to her was 26 August 1921 (BRACERS 19742).

Marie Blanche

Marie Blanche (1891–1973) studied at the Academy of Dramatic Arts where she met Colette. She sang as well as acted and had a successful career on the London stage in the 1920s. A photograph of her appeared in The Times, 20 March 1923, p. 16.

Miles Malleson

Miles Malleson (1888–1969), actor and playwright, was born in Croydon, Surrey, the son of Edmund and Myrrha Malleson. He married his first wife, a fellow actor, Lady Constance Annesley (stage name, Colette O’Niel), in 1915. They had met at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts). Their marriage was an “open” one. In 1914 Miles enlisted in the City of London Fusiliers and was sent to Malta. He became ill and was discharged, unfit for further service. He became active in the No-Conscription Fellowship and wrote anti-war stage plays as well as a pamphlet, Cranks and Commonsense (1916). In the 1930s he began to write for the screen and act in films, in which he became a very well-known character actor, as well as continuing his stage career at the Old Vic in London. He married three times: his second marriage was to Joan Billson, a physician (married 1923, divorced 1940), with whom he had two children; his third wife was Tatiana Lieven, an actress (married 1946). He died in London in March 1969.

Raphael Demos

Raphael Demos (1892–1968), one of BR’s logic students in the autumn of 1916. Then on a Sheldon travelling fellowship, Demos eventually returned to Harvard where he taught philosophy for the rest of his career. Russell had taught him at Harvard in 1914 and described him in his Autobiography (1: 212). In 1916–17 BR recommended two of his articles to G.F. Stout, the editor of Mind (“A Discussion of a Certain Type of Negative Proposition”, Mind 26 [Jan. 1917]: 188–96; and “A Discussion of Modal Propositions and Propositions of Practice”, 27 [Jan. 1918]: 77–85); see BRACERS 54831 and 2962 (and for Demos’s letters to BR in 1917 about the submissions, BRACERS 76495 and 76496, and BR’s reply to the first, BRACERS 838).

Russell Chambers

34 Russell Chambers, Bury Street (since renamed Bury Place), London WC1, BR’s flat since 1911. Helen Dudley rented the flat in late 1916 or early 1917. In May 1918 she sublet it to Clare Annesley. Colette moved in on 9 September 1918 and stayed until June 1919. BR did not give up the lease until December 1923. See S. Turcon, “Russell Chambers, Other London Flats, and Country Homes, 1911–1923”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 150 (Fall 2014): 30–4. “Russell Chambers, Other London Flats, and Country Homes, 1911–1923”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 150 (Fall 2014): 30–4.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.