Brixton Letter 27

BR to Frank Russell

June 24, 1918

- ALS

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-27

BRACERS 46921

<Brixton Prison>1

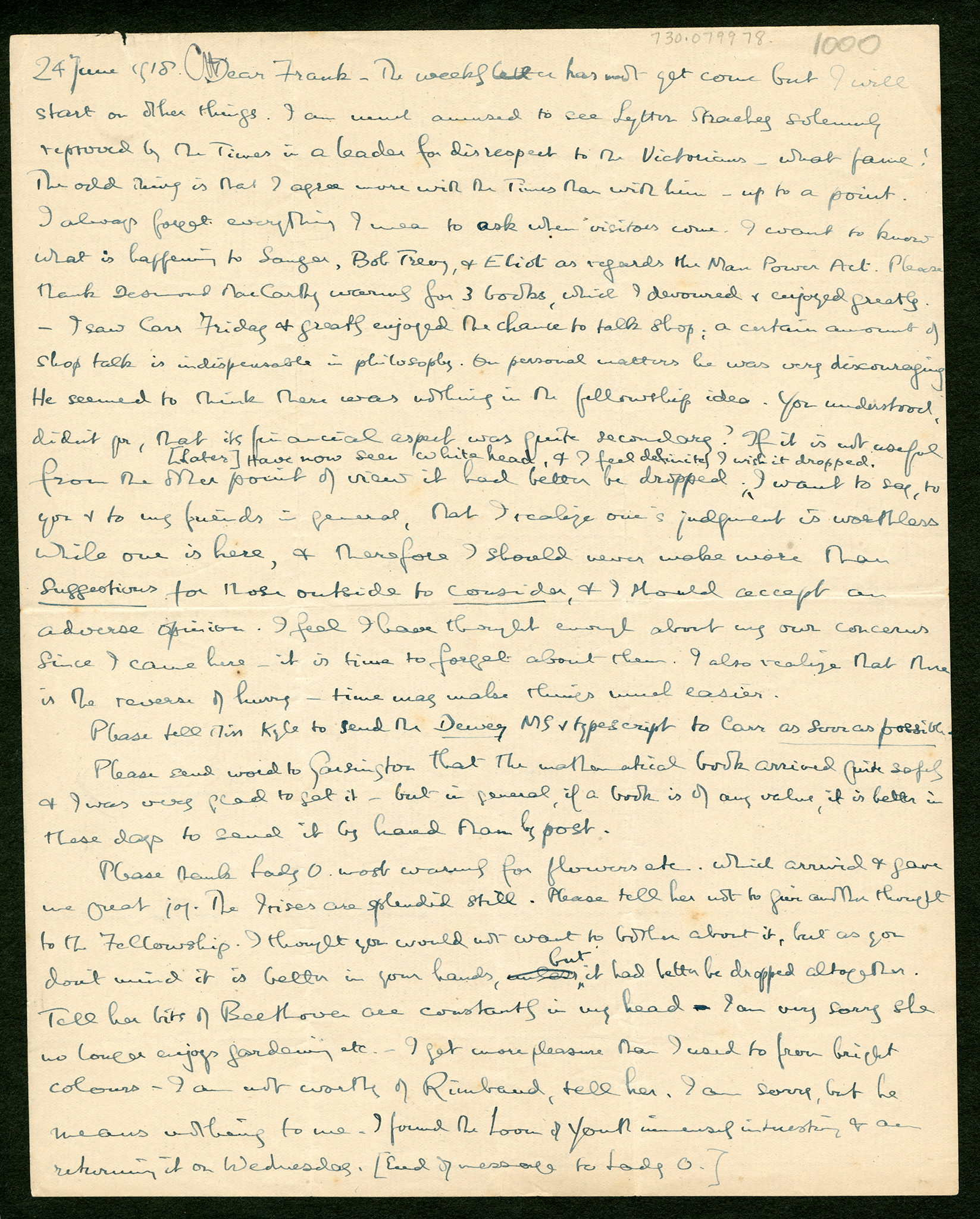

24 June 1918.

Dear Frank

The weekly letter2 has not yet come but I will start on other things. I am much amused to see Lytton Strachey solemnly reproved by the Times3 in a leader for disrespect to the Victorians — what fame! The odd thing is that I agree more with the Times than with him — up to a point. I always forget everything I mean to ask when visitors come. I want to know what is happening to Sanger, Bob Trevy, and Eliot as regards the Man Power Act.4 Please thank Desmond MacCarthy warmly for 3 books, which I devoured and enjoyed greatly. — I saw Carr Friday and greatly enjoyed the chance to talk shop; a certain amount of shop talk is indispensable in philosophy. On personal matters he was very discouraging. He seemed to think there was nothing in the fellowship idea. You understood, didn’t you, that its financial aspect was quite secondary? If it is not useful from the other point of view it had better be dropped. [Later] Have now seen Whitehead, and I feel definitely I wish it dropped.a I want to say, to you and to my friends in general, that I realize one’s judgment is worthless while one is here, and therefore I should never make more than suggestions for those outside to consider, and I should accept an adverse opinion. I feel I have thought enough about my own concerns since I came here — it is time to forget about them. I also realize that there is the reverse of hurry — time may make things much easier.

Please tell Miss Kyle to send the Dewey MS and typescript5 to Carr as soon as possible.

Please send word to Garsington that the mathematical book6 arrived quite safely and I was very glad to get it — but in general, if a book is of any value, it is better in these days to send it by hand than by post.

Please thank Lady O. most warmly for flowers etc. which arrived and gave me great joy. The Irises are splendid still. Please tell her not to give another thought to the Fellowship. I thought you would not want to bother about it, but as you don’t mind it is better in your hands, but it had betterb be dropped altogether. Tell her bits of Beethoven are constantly in my head — I am very sorry she no longer enjoys gardening etc. — I get more pleasure than I used to from bright colours. I am not worthy of Rimbaud, tell her. I am sorry, but he means nothing to me.7 I found the Loom of Youth8 immensely interesting and am returning it on Wednesday. [End of message to Lady O.]

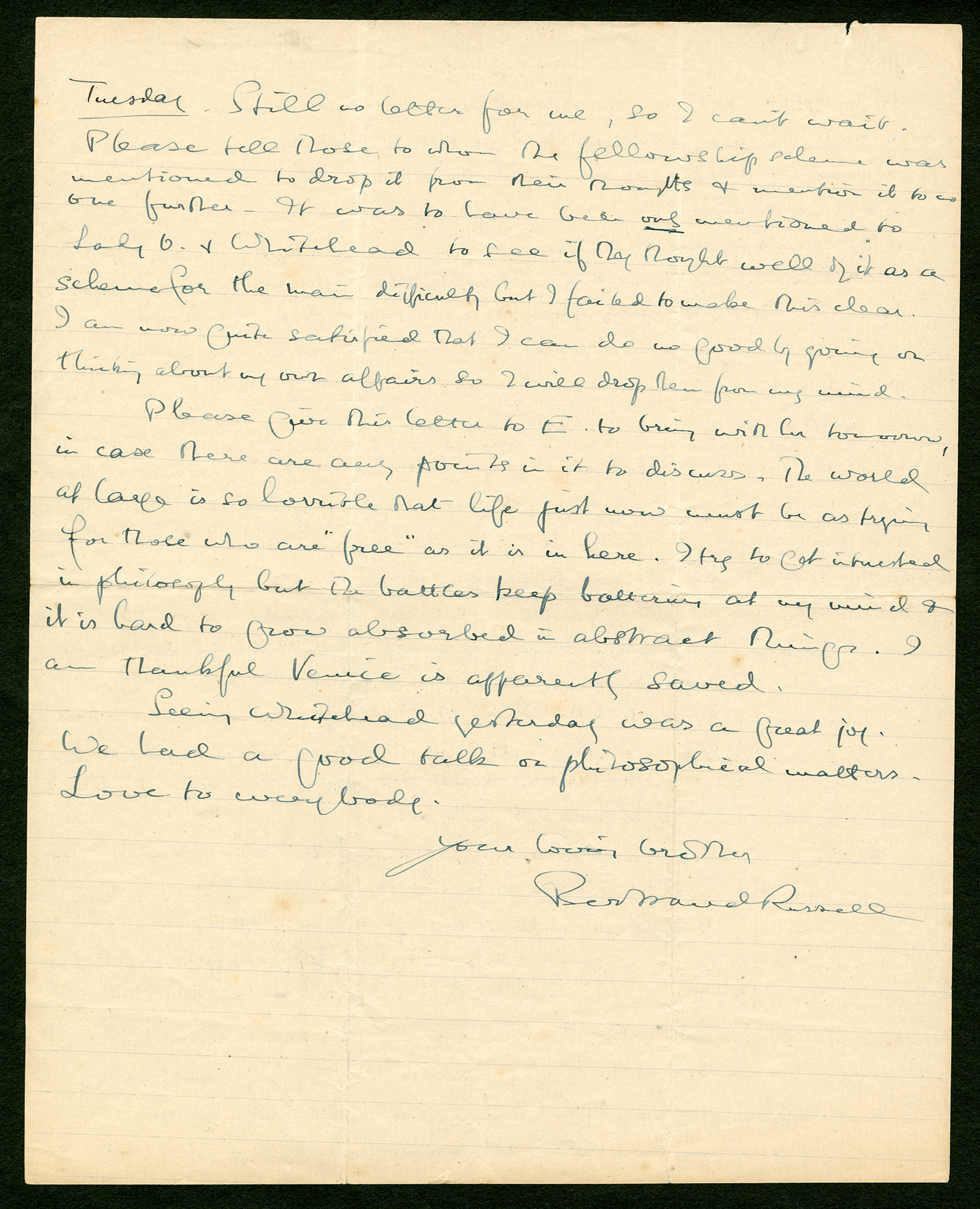

Tuesday.

Still no letter for me, so I can’t wait. Please tell those to whom the fellowship scheme was mentioned to drop it from their thoughts and mention it to no one further. It was to have been only mentioned to Lady O. and Whitehead to see if they thought well of it as a scheme for the main difficulty but I failed to make this clear. I am now quite satisfied that I can do no good by going on thinking about my own affairs so I will drop them from my mind.

Please give this letter to E. to bring with her tomorrow, in case there are any points in it to discuss. The world at large is so horrible that life just now must be as trying for those who are “free” as it is in here. I try to get interested in philosophy but the battles keep battering at my mind and it is hard to grow absorbed in abstract things. I am thankful Venice is apparently saved.9

Seeing Whitehead yesterday was a great joy. We had a good talk on philosophical matters. Love to everybody.

Your loving brother

Bertrand Russell

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from BR’s signed, handwritten, single-sheet original in Frank Russell’s files in the Russell Archives. It was an “official” letter, approved by “CH”, the Brixton governor, despite not being written on the blue correspondence form of the prison system.

- 2

The weekly letter Dated 22–28 June 1918 (BRACERS 46920).

- 3

Lytton Strachey solemnly reproved by the Times “History has no business to be flippant, and the flippant judgment, masquerading sometimes as a manifestation of the Comic Spirit, is never just” (“The Victorians”, 24 June 1918, p. 9). This editorial had been prompted by Herbert Asquith’s recent Romanes lecture, Some Aspects of the Victorian Age (Oxford: Clarendon P., 1918), in which the late Prime Minister praised Strachey’s treatment of the period. While acknowledging the literary merits of Eminent Victorians (1918), The Times regarded Strachey as a far from “perfect witness” to an era now deserving of “judgment less self-conscious and more sympathetic”.

- 4

Sanger, Bob Trevy, and Eliot as regards the Man Power ActC.P. Sanger and Robert Calverley Trevelyan (1872–1951), poet and translator, were old and close Cambridge friends of BR’s. Since April 1918 both men (like BR) had been subject to the terms of the Military Service (No. 2) Act — i.e., the (amended) Man Power Act — which raised the upper-age limit for conscripts to 50. The fate of Sanger, whose views on the war were similar to BR’s (see Auto. 2: 44), remains unknown, but he does not appear to have been called up. Trevelyan pre-empted a possible call-up by volunteering to work for the (Quaker) Friends’ War Victims Relief Service. The situation of T.S. Eliot, a much younger American, was more complicated. On 30 July 1918 Britain and the United States had ratified a convention authorizing the conscription of each other’s resident alien nationals. In a message conveyed by Gladys Rinder on 17 August, Vivienne Eliot alerted BR about “a new call up for all Americans here under 30, coming into force before Sept 30th” (BRACERS 79619). But Eliot could still preempt this outcome by enlisting in the US armed forces, in which the service of married men had been temporarily deferred. In another letter to BR, dated 17 August, Rinder outlined Eliot’s intention “to register in the American Army, ask for exemption as a married man, and in the meantime if possible get a post in the Intelligence Department or some other branch of the Army more suited to his capacities than general service” (BRACERS 46932). Early in August Eliot was passed medically fit by the US Navy, in which he served very briefly after being called up in the final weeks of the war. See also Letter 78.

- 5

Dewey MS and typescript See “Professor Dewey’s Essays in Experimental Logic”, The Journal of Philosophy, Psychology and Scientific Methods 16 (2 Jan. 1919): 5–26 (B&R C19.02); 16 in Papers 8. BR completed his 10,000 word review by early June (see note 14 to Letter 15 and note 18 to Letter 12). Carr was to look after sending it to the US. (For receipt of proofs, see Letter 95, note 12.) Russell’s library holds the copy of Essays in Experimental Logic (Chicago: U. of Chicago P., 1916) that he read and annotated during his imprisonment.

- 6

the mathematical book The unspecified book was doubtless one used to smuggle letters.

- 7

Rimbaud, tell her ... he means nothing to me After sending him Paterne Berrichon’s critical study of the French symbolist Arthur Rimbaud (1854–1891), and possibly the poet’s own Une saison en enfer (BRACERS 46919 and 19326), Ottoline anticipated it being “touch and go” as to whether BR would be drawn towards “that strange — obscure — creation”. But “I Love him”, she declared in this letter of 1 June 1918 (BRACERS 114746). “I don’t know why. — I suppose because he evidently suffered intensely and his mind and imagination was forever working — translating objects into something spiritual and vivid — concrete spiritual images.” See also Letters 15, 20 and 31.

- 8

The Loom of Youth A mildly homoerotic (but still risqué), semi-autobiographical novel (London: Richards, 1918) about English public school life. When BR read it, the author, Alec Waugh (1898–1981), was in a German prisoner-of-war camp. His younger brother became the well-known novelist Evelyn Waugh.

- 9

Venice is apparently saved Fighting in the second Battle of the Piave River (15–23 June 1918) came within about twenty miles of Venice to the southeast. If Austro-Hungarian forces had been able then to establish a secure bridgehead across the river, the city would, indeed, have been imperilled. But Italian (and French) troops successfully repelled the offensive and inflicted a decisive strategic blow on the Central Powers. The morale and cohesion of the Habsburg army were sapped by this crushing defeat, which was a prelude to the collapse of the empire itself only months later.

Textual Notes

A.N. Whitehead

Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947), Cambridge-educated mathematician and philosopher. From 1884 to 1910 he was a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, and lecturer in mathematics there; from 1911 to 1924 he taught in London, first at University College and then at the Imperial College of Science and Technology; in 1924 he took up a professorship in philosophy at Harvard and spent the rest of his life in America. BR took mathematics courses with him as an undergraduate, which led to a lifelong friendship. Whitehead’s first major work was A Treatise on Universal Algebra (1898), which treated selected mathematical theories as “systems of symbolic reasoning”. Like BR’s The Principles of Mathematics (1903), it was intended as the first of two volumes; but in 1900 he and BR discovered Giuseppe Peano’s work in symbolic logic, and each decided to set aside his projected second volume to work together on a more comprehensive treatment of mathematics using Peano’s methods. The result was the three volumes of Principia Mathematica (1910–13), which occupied the pair for over a decade. After Principia was published, Whitehead’s interests, like BR’s, turned to the empirical sciences and, finally, after his move to America, to pure metaphysics. See Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: the Man and His Work, 2 vols. (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins U. P., 1985–90).

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

C.P. Sanger

Charles Percy Sanger (1871–1930) and BR remained close friends after their first-year meeting at Trinity College, to which both won mathematics scholarships and where their brilliance was almost equally rated. They were elected to the Cambridge Apostles and obtained their fellowships at the same time. After being called to the Bar, Sanger became an erudite legal scholar and was an able economist with great facility in languages as well. BR fondly recalled his “perfect combination of penetrating intellect and warm affection” (Auto. 1: 57).

Desmond MacCarthy

(Charles Otto) Desmond MacCarthy (1877–1952), literary critic, Cambridge Apostle, and a friend of BR’s since their Trinity College days in the 1890s. MacCarthy edited the Memoir (1910) of Lady John Russell.

Elizabeth Russell

Elizabeth Russell, born Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941), was a novelist who in 1891 married Graf von Arnim-Schlagenthin. She became known as “Elizabeth”, the name she used in publishing Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898), and she remained widely known as Elizabeth von Arnim, although the Library of Congress catalogues her as Mary Annette (Beauchamp), Countess von Arnim. She was a widow when she married BR’s brother, Frank, on 11 February 1916. The marriage was quickly in difficulty; she left it for good in March 1919, but they were never divorced and she remained Countess Russell (becoming Dowager Countess after Frank’s death in 1931).

Eva Kyle

Eva Kyle ran a typing service. She did work for the No-Conscription Fellowship and took BR’s dictation of his book, Roads to Freedom, in the early months of 1918. He annotated a letter from her: “She was an admirable typist but very fat. We all agreed that she was worth her weight in gold, though that was saying a great deal.” Her prison letter to him is clever and amusing. She typed his major prison writings and apologized for the amount of the invoice when he emerged.

Fellowship Plan

Since the upper-age limit for compulsory military service had been increased to 50 in April 1918, BR was faced with the unnerving prospect of being conscripted after his release from Brixton. Early in his imprisonment he was already wondering about his “position when I emerge from here” (Letter 9). While his conviction was still under appeal, he had broached with Clifford Allen and Gilbert Murray the possibility of avoiding military service, not by asserting his conscientious objection to it, but by obtaining accreditation of his philosophical research as work of national importance (see note to Letter 24). The Pelham Committee, set up by the Board of Trade in March 1916, was responsible for the designation of essential occupations and recommending to the local tribunals, who adjudicated claims for exemption from military service, that C.O.s be considered for such positions. BR reasoned to Murray on 2 April that a dispensation to practise philosophy (as opposed to working outside his profession), would enable to him to “avoid prison without compromise” — i.e., of his political and moral opposition to conscription (BRACERS 52367). Although BR intended to withdraw from political work, he told Murray two days later, he would not promise to abstain from peace campaigning (BRACERS 52369). It should be noted that C.O.s who accepted alternative service in special Home Office camps were expressly prohibited from engaging in pacifist activities (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 231).

BR was far from sanguine about the prospect of success before a local tribunal. But he came to think (by early June) that his chances would be improved if his academic supporters interceded directly with the Minister of National Service, Sir Auckland Geddes. In addition, he calculated that such entreaties would be more effective if those acting on his behalf could secure and even endow a fellowship for him and thereby have “something definite to put before Geddes” (Letter 12; see also Letters 15 and 19). BR definitely wanted to rededicate himself to philosophy and would have welcomed a new source of income from academic employment (see Letter 22). But the “financial aspect was quite secondary”, he reminded Frank on 24 June (Letter 27); he was interested in the fellowship plan primarily as a safeguard against being called up, for teachers over 45 were not subject to the provisions of the recently amended Military Service Act. In the same letter, however, BR told his brother that “I wish it <the plan> dropped” on account of reservations expressed to him in person by Wildon Carr and A.N. Whitehead (see also Letter 31), two philosophers whom he respected but who seemed to doubt whether BR’s financial needs were as great as they appeared (see note to Letter 102).

Yet BR’s retreat was only temporary. On 8 August, he expressed to Ottoline a renewed interest in the initiative, and a few days later, she, her husband and Gladys Rinder met in London to discuss the matter. As Ottoline reported to BR, “we all felt that it was useless to wait for others to start and we decided that P. and I should go and see Gilbert M. and try and get him to work it with the Philosophers” (11 Aug. 1918, BRACERS 114754). BR probably wanted Murray to spearhead this lobbying (see also Letters 65 and 70) because of his political respectability and prior success in persuading professional philosophers to back an appeal to the Home Secretary for BR’s sentence to be served in the first division (see Letter 6). Murray did play a leading role but not until early the following month, when BR was anxious for the fellowship plan to succeed as his release date neared. The scheme finally gathered momentum after a meeting between Ottoline, Rinder and Carr on 6 September 1918, at which the philosopher and educationist T. Percy Nunn, another academic supporter of BR, was also present. Within a few days Murray had drafted a statement with an appeal for funds, which was endorsed by Carr, Whitehead, Nunn, Samuel Alexander, Bernard Bosanquet, G. Dawes Hicks, A.E. Taylor and James Ward. This memorial was then circulated in confidence to philosophers and others, but only after BR’s release from Brixton. (Financial pledges had already been made by a few of BR’s friends and admirers, notably Lucy Silcox and Siegfried Sassoon.) BR’s solicitor, J.J. Withers, became treasurer of this endowment fund, the goal of which was to provide BR with £150 or £200 per annum over three years. On 30 August BR had confessed to Ottoline that he did not want an academic position “very far from London” (Letter 89) and reiterated this desire in a message to Murray communicated by Rinder (Letter 97). On 6 September Rinder (BRACERS 79633) hinted that she already knew where the appointment would be, but there are no other indications that a particular establishment had been decided upon. Ultimately, no affiliation was contemplated for BR, so the memorial stated, because “in the present state of public feeling no ordinary university institution is likely to be willing to employ him as a teacher” (copy in BRACERS 56750). The circular talked instead of a “special Lectureship”, and the £100 BR received from the fund early in 1919 was explicitly issued as payment for lectures (on “The Analysis of Mind”; see syllabus, in Papers 9: App. III.1) that he would deliver that spring. BR’s solicitor also informed him that provision existed to pay him a further £100 for an autumn lecture course (see syllabus, ibid.: App. III.2), and Withers anticipated that these arrangements might “last two or three years” (2 Jan. 1919, BRACERS 81764). BR had already obtained a £50 gift from the fund in November 1918. Somewhat ironically, the critical importance of a teaching component to the fellowship plan — as insurance against conscription — was reduced by the authorities hesitating to hound BR any further after his imprisonment, and all but nullified by the end of the war a few weeks later. (There were no fresh call-ups, but the last of the C.O.s already in prison were not released until August 1919, and conscription remained in effect until April 1920.)

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Governor of Brixton Prison / Carleton Haynes

Captain Carleton Haynes (1858–1945), the Governor of Brixton Prison in 1918, was a retired army officer and a cousin of BR’s acquaintance, the radical lawyer and author E.S.P. Haynes. In March 1919 BR sent Haynes, in jest, a copy (now in the Russell Archives) of his newly published Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy — so that the governor’s collection of works written by inmates while under his charge would “not ... be incomplete” (BRACERS 123167).

H. Wildon Carr

Herbert Wildon Carr (1857–1931), Professor of Philosophy at King’s College, London, from 1918 and Visiting Professor at the University of Southern California from 1925. Carr came to philosophy late in life after a lucrative career as a stockbroker. His philosophy was an idiosyncratic amalgam of Bergsonian vitalism and Leibnizian monadology, which, he thought, was supported by modern biology and the theory of relativity. He wrote books on Bergson and Leibniz at opposite ends of his philosophical career and a book on relativity in the middle. His philosophy would have made him an unlikely ally of BR’s, but it was Carr who organized BR’s two courses of public lectures, on philosophy of mathematics and the philosophy of logical atomism, which brought BR back to philosophy and improved his finances in 1917–18. Carr had great administrative talents, which he employed also on behalf of the Aristotelian Society during his long association with it. He was its president in 1916–18 and continued to edit its Proceedings until 1929.

Lytton Strachey

Lytton Strachey (1880–1932), biographer, reviewer and a quintessential literary figure of the Bloomsbury Group. He is best known for his debunking portraits of Cardinal Manning, Florence Nightingale, Dr. Arnold and General Gordon, published together as Eminent Victorians (London: Chatto & Windus, 1918; Russell’s library), which BR read in Brixton with great amusement as well as some critical reservations (see Letter 7). Although Strachey was homosexual, he and the artist Dora Carrington were devoted to each other and from 1917 lived together in Tidmarsh, Berkshire. BR had become acquainted with the somewhat eccentric Strachey, a fellow Cambridge Apostle, while his slightly younger contemporary was reading history at Trinity College. He admired Strachey’s literary gifts, but doubted his intellectual honesty. Almost three decades later BR fleshed out the unflattering thumbnail of Strachey drawn for Ottoline in Letter 7, in a “Portrait from Memory” for BBC radio. Strachey was “indifferent to historical truth”, BR alleged in that broadcast, “and would always touch up the picture to make the lights and shades more glaring and the folly or wickedness of famous people more obvious” (The Listener 48 [17 July 1952]: 98). Main biography: Michael Holroyd, Lytton Strachey: a Critical Biography, 2 vols. (London: Heinemann, 1967–68).

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

T.S. Eliot

The poet and critic Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888–1965) was a student of BR’s at Harvard in 1914. BR had sensed his ability, especially “a certain exquisiteness of appreciation” (to Lucy Donnelly, 11 May 1914; SLBR 1: 491), but did not see a genius in embryo. After Eliot travelled to England later the same year, to study philosophy at Oxford under H.H. Joachim, BR became something of a father figure to the younger man. He also befriended Eliot’s (English) wife, Vivienne, whom he had hastily married in 1915 and with whom BR may have had an affair the following year. BR shared his Bloomsbury apartment (at 34 Russell Chambers) with the couple for more than a year after their marriage, and jointly rented a property with them in Marlow, Bucks. (see Letter 78). He further eased Eliot’s monetary concerns by arranging paid reviewing for him and giving him £3,000 in debentures from which BR was reluctant, on pacifist grounds, to collect the income (Auto. 2: 19). Eliot’s financial security was much improved by obtaining a position at Lloyd’s Bank in 1917, but during BR’s imprisonment he faced uncertainty of a different kind as the shadow of conscription loomed over him (see, e.g., Letter 27). Nine years after the war ended Eliot returned the securities (BRACERS 76480).

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).