Brixton Letter 25

BR to Constance Malleson

June 22, 1918

- AL

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-25

BRACERS 19313

<Brixton Prison>1

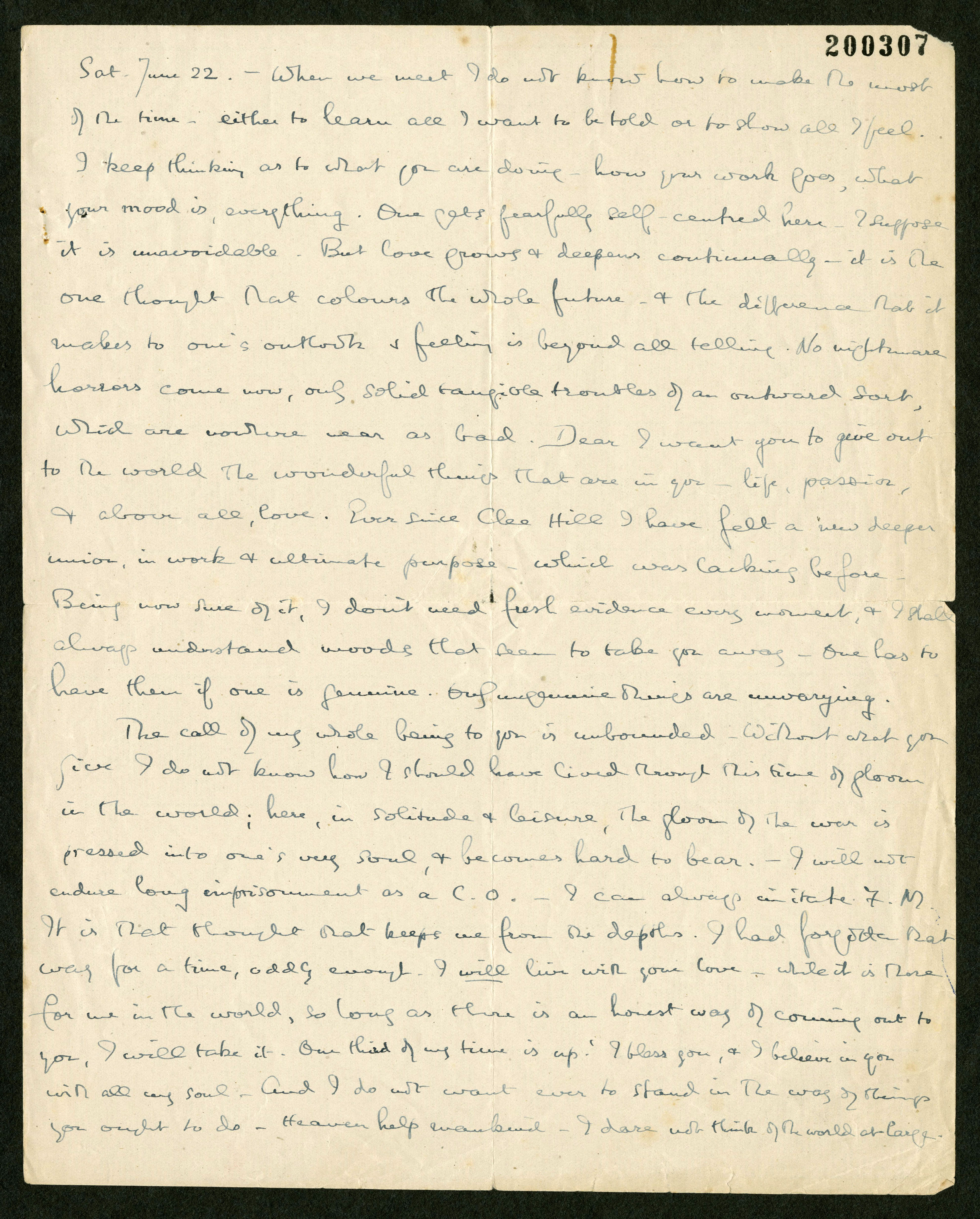

Sat. June 22.

When we meet2 I do not know how to make the most of the time — either to learn all I want to be told or to show all I feel. I keep thinking as to what you are doing — how your work goes,3 what your mood is, everything. One gets fearfully self-centred here — I suppose it is unavoidable. But love grows and deepens continually — it is the one thought that colours the whole future — and the difference that it makes to one’s outlook and feeling is beyond all telling. No nightmare horrors come now, only solid tangible troubles of an outward sort, which are nowhere near as bad. Dear I want you to give out to the world the wonderful things that are in you — life, passion, and above all, love. Ever since Clee Hill I have felt a new deeper union, in work and ultimate purpose — which was lacking before. Being now sure of it, I don’t need fresh evidence every moment, and I shall always understand moods that seem to take you away. One has to have them if one is genuine. Only ungenuine things are unvarying.

The call of my whole being to you is unbounded. Without what you give I do not know how I should have lived through this time of gloom in the world; here, in solitude and leisure, the gloom of the war is pressed into one’s very soul, and becomes hard to bear. — I will not endure long imprisonment as a C.O.4 — I can always imitate F.M.5 It is that thought that keeps me from the depths. I had forgotten that way for a time, oddly enough. I will live with your love — while it is there for me in the world, so long as there is an honest way of coming out to you, I will take it. One third of my time is up!6 I bless you, and I believe in you with all my soul. And I do not want ever to stand in the way of things you ought to do. Heaven help mankind. I dare not think of the world at large.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the unsigned original in BR’s handwriting in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. The sheet is lined on one side and folded twice.

- 2

When we meet Colette expected to visit BR in prison on 26 June. He was allowed one visit of three people for half an hour, once a week, every Tuesday or Wednesday, apart from business visitors. Early in his incarceration Colette had been in Manchester and then York and Scarborough. She was touring with a theatre company, playing the role of Mabel in Phyl (author unknown) She had made at least one visit by 4 June (before she left on that tour) because in a letter she wrote that day she mentioned she had already visited Brixton (BRACERS 113134).

- 3

your work goesColette wrote in reply on 24 June that she was still full of energy from the tour. She and Miles were thinking of starting an Experimental Theatre from which Miles would be able to earn a small income (BRACERS 113135).

- 4

imprisonment as a C.O. BR was hinting at the possibility of prolonged detention in military or civil custody, should he be called up for military service after his release from Brixton, have his claim for absolute exemption rejected, then refuse to undertake “alternative” war work. In April 1918 the upper-age limit for British conscripts had been raised from 40 to 50 (see note 5 to Letter 6).

- 5

imitate F.M. And go on a hunger strike. Francis Meynell describes his hunger strike in detail in My Lives (London: Bodley Head, 1971), pp. 99–103. He was not in prison, however, but at Hounslow Barracks with other C.O.s from 29 January 1917. He collapsed after twelve days without food or water and got a unconditional discharge from the army after agreeing to take nourishment.

- 6

One third of my time is up! BR had then been imprisoned for 53 days. To calculate that one third of his time was up, he must have projected being released in early October (2 October would have marked 155 days) and been cognizant of the general rule stated by Sir George Cave to Frank when the brothers hoped for an even earlier remission: “The Prison Commissioners, however, are able under the rules to grant remission up to one-sixth of the sentence to prisoners who earn it by good conduct and industry, and I have informed them that they would be justified, in view of the work which your brother has been doing during his imprisonment, in awarding him the full number of marks, that is to say, he will only be required to serve five months instead of six and will be due for release at the end of September” (5 Aug. 1918., BRACERS 57178). This was official confirmation of a release date slightly earlier than the date of 2 October to be found in the Home Office file minutes. An even earlier date was going to be considered by Cave (see Letter 52).

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Clee Hill

Near Ashford Carbonel, Shropshire, where BR and Colette spent an idyllic summer holiday in August 1917, staying in house named “The Avenue”. BR mentioned the day at Clee Hill in several letters, the last on 8 September 1918 (Letter 100). What exactly happened on that day is not clear in any of his letters. However, in a prison message to BR, Colette remembered that a red fox came and listened to them there (Rinder to BR, 15 June 1918, BRACERS 79614). They also vacationed at The Avenue in March 1918, before BR entered prison.

Experimental Theatre

Colette first mentioned that she and Miles were trying to start an Experimental Theatre in a letter of 24 June 1918 (BRACERS 113135), indicating that Miles would earn a tiny income from it. About a month later, she wrote that Elizabeth Russell had subscribed generously to the Theatre and that £700 had been raised, but hundreds still had to be found (BRACERS 113146). A few days later she wrote that Captain Stephen Gordon, a north-country lawyer working for the government, was to be the honorary treasurer, noting that he had “put most of the drive into the whole thing” (BRACERS 113147). During August Colette was happy with her involvement with the Theatre (Letter 68). John Galsworthy came to tea to discuss the project (c.14 Aug., BRACERS 113149). On 2 September she listed the members of the Theatre committee as “Desmond <MacCarthy>, Massingham, Galsworthy, and Dennis (Bradley)” (BRACERS 113155). The following day she wrote that she was learning three parts (BRACERS 113156). In her memoirs, Colette wrote about the “Experimental Little Theatre” but dated it 1919 (After Ten Years [London: Cape, 1931], pp. 129–30). An “artistic” theatre did get founded in 1920 in Hampstead, and John Galsworthy was connected to that venture, The Everyman Theatre — he was part of a reading committee which chose the works to be performed (The Times, 9 Sept. 1919, p. 8). The Everyman Theatre was under the direction of Norman MacDermott. In his book Everymania (London: Society for Theatre Research, 1975), he noted that he met Miles in the summer of 1918: they rented a store in Bloomsbury, had a cabinetmaker build sets, and put on plays with actors “bored with West-End theatres” (p. 10). It is likely that the Everyman Theatre was an out-growth of the Experimental Theatre.

Francis Meynell

Francis Meynell (1891–1975; knighted 1946), journalist, publisher, and graphic designer, was one of BR’s colleagues in the No-Conscription Fellowship. After being called up in 1916 and refusing to serve, he was detained in military custody at Hounslow Barracks; he was released after a twelve-day hunger strike (see Letter 24). In 1915 Meynell founded the Pelican Press as a publishing outlet for peace propaganda and was also a contributing editor for the Independent Labour Party’s resolutely anti-war Daily Herald. BR evidently respected the political tenacity of Meynell, who remembered being told by him that “I like you … because in spite of your spats there is much of the guttersnipe about you” (Francis Meynell, My Lives [London: The Bodley Head, 1971], p. 89).

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).

Home Secretary / Sir George Cave

Sir George Cave (1856–1928; Viscount Cave, 1918), Conservative politician and lawyer, was promoted to Home Secretary (from the Solicitor-General’s office) on the formation of the Lloyd George Coalition in December 1916. His political and legal career peaked in the 1920s as Lord Chancellor in the Conservative administrations led by Andrew Bonar Law and Stanley Baldwin. At the Home Office Cave proved to be something of a scourge of anti-war dissent, being the chief promoter, for example, of the highly contentious Defence of the Realm Regulation 27C (see Letter 51).

Miles Malleson

Miles Malleson (1888–1969), actor and playwright, was born in Croydon, Surrey, the son of Edmund and Myrrha Malleson. He married his first wife, a fellow actor, Lady Constance Annesley (stage name, Colette O’Niel), in 1915. They had met at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts). Their marriage was an “open” one. In 1914 Miles enlisted in the City of London Fusiliers and was sent to Malta. He became ill and was discharged, unfit for further service. He became active in the No-Conscription Fellowship and wrote anti-war stage plays as well as a pamphlet, Cranks and Commonsense (1916). In the 1930s he began to write for the screen and act in films, in which he became a very well-known character actor, as well as continuing his stage career at the Old Vic in London. He married three times: his second marriage was to Joan Billson, a physician (married 1923, divorced 1940), with whom he had two children; his third wife was Tatiana Lieven, an actress (married 1946). He died in London in March 1969.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.