Brixton Letter 99

BR to Constance Malleson

September 7, 1918

- AL

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-99

BRACERS 19359

<Brixton Prison>1

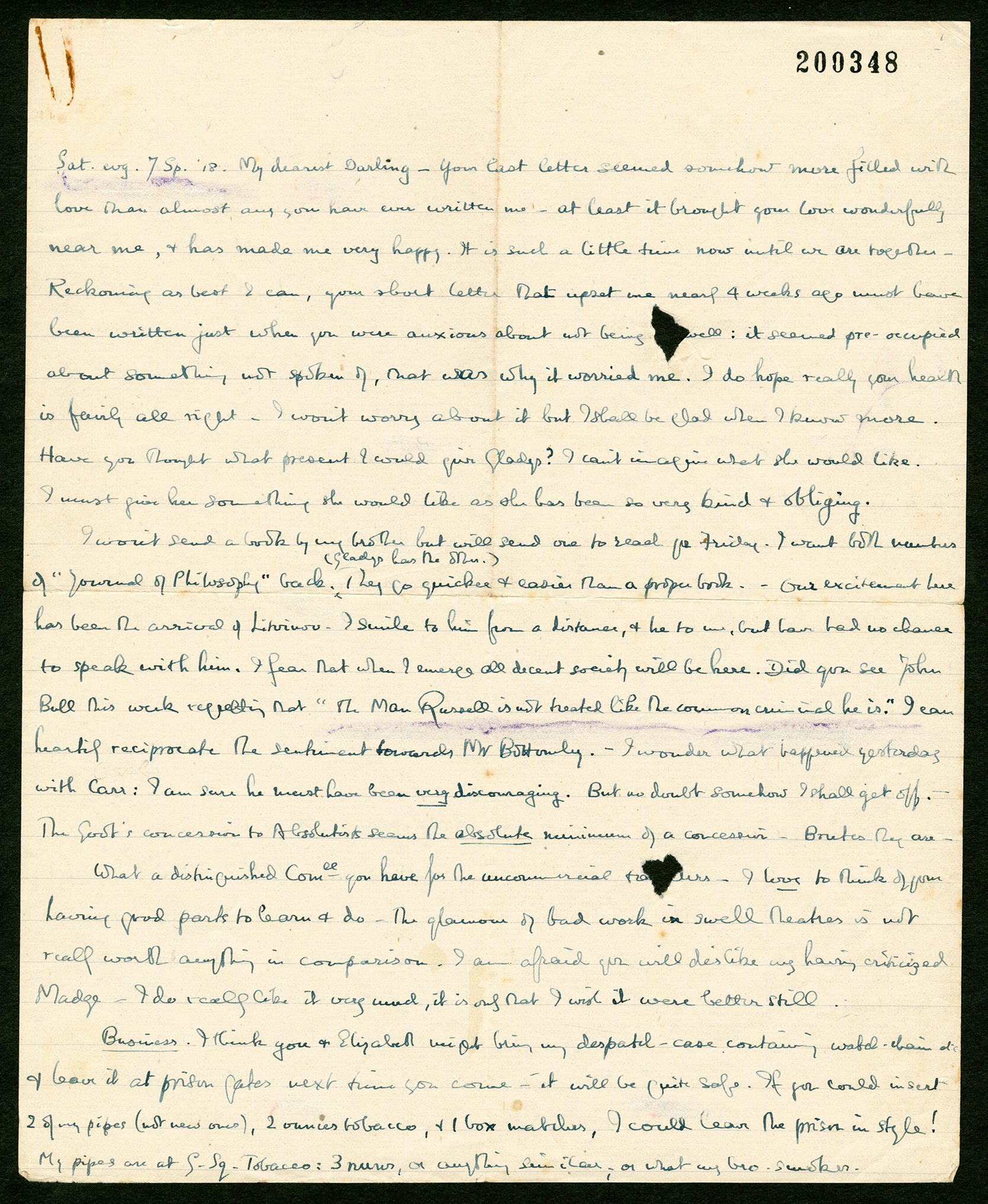

Sat. evg. 7 Sp. ’18.

My dearest Darling

Your last letter seemed somehow more filled with love2 than almost any you have ever written me — at least it brought your love wonderfully near me, and has made me very happy. It is such a little time now until we are together. Reckoning as best I can, your short letter that upset me nearly 4 weeks ago3 must have been written just whena you were anxious about not being <hole in paper>b well: it seemed pre-occupied about something not spoken of, that was why it worried me. I do hope really your health4 is fairly all right. I won’t worry about it but I shall be glad when I know more. Have you thought what present I could give Gladys?5 I can’t imagine what she would like. I must give her something she would like as she has been so very kind and obliging.

I won’t send a book by my brother but will send one to reach you Friday. I want both numbers of Journal of Philosophy back.6 (Gladys has the other.)c They go quicker and easier than a proper book.7 — Our excitement here has been the arrival of Litvinov. I smile to him8 from a distance, and he to me, but have had no chance to speak with him. I fear that when I emerge all decent society will be here. Did you see John Bull this week9 regretting that “the Man Russell is not treated like the common criminal he is.” I can heartily reciprocate the sentiment towards Mr Bottomley.10— I wonder what happened yesterday with Carr:11 I am sure he must have been very discouraging. But no doubt somehow I shall get off. — The Govt’s concession to Absolutists12 seems the absolute minimum of a concession. Brutes they are.

What a distinguished Comee.13 you have for the uncommercial travellers.14, d I love to think of your having good parts to learn and do15 — the glamour of bad work in swell theatres is not really worth anything in comparison. I am afraid you will dislike my having criticized “Madge”16, e — I do really like it very much, it is only that I wish it were better still.

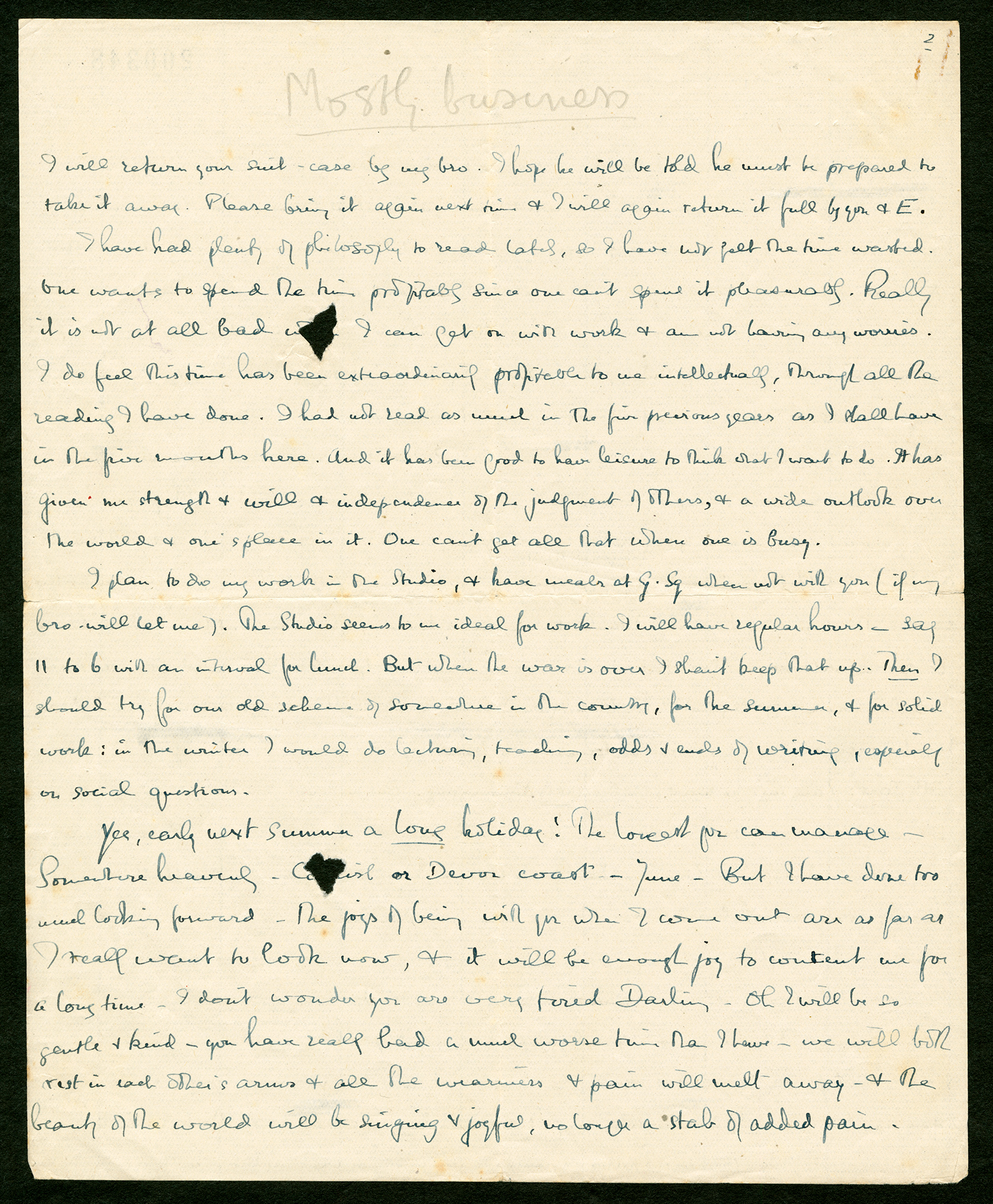

Business.f I think you and Elizabeth might bring my despatch-case containing watch-chain etc. and leave it at prison gates next time you come — it will be quite safe. If you could insert 2 of my pipes (not new ones), 2 ounces tobacco, and 1 box of matches, I could leave the prison in style! My pipes are at G. Sq. Tobacco: 3 nuns, or anything similar; or what my brother smokes.17 I will return your suit-case18 by my brother. I hope he will be told he must be prepared to take it away. Please bring it again next time and I will again return it full by you and E.19

I have had plenty of philosophy to read lately, so I have not felt the time wasted. One wants to spend the time profitably since one can’t spend it pleasurably. Really it is not at all bad when I can get on with work and am not having any worries. I do feel this time has been extraordinarily profitable to me intellectually, through all the reading I have done. I had not read as much in the five previous years as I shall have in the five months here. And it has been good to have leisure to think what I want to do. It has given me strength and will and independence of the judgment of others, and a wide outlook over the world and one’s place in it. One can’t get all that when one is busy.

I plan to do my work in the Studio, and have meals at G. Sq. when not with you (if my brother will let me). The Studio seems to me ideal for work. I will have regular hours — say 11 to 6 with an interval for lunch. But when the war is over I shan’t keep that up. Then I should try for our old scheme of somewhere in the country, for the summer, and for solid work: in the winter I would do lecturing, teaching, odds and ends of writing, especially on social questions.

Yes, early next summer a long holiday! The longest you can manage — somewhere heavenly — Cornishg or Devon coast — June. But I have done too much looking forward — the joys of being with you when I come out are as far as I really want to look now, and it will be enough joy to content me for a long time. I don’t wonder you are very tired Darling. Oh I will be so gentle and kind — you have really had a much worse time than I have20 — we will both rest in each other’s arms and all the weariness and pain will melt away — and the beauty of the world will be singing and joyful, no longer a stab of added pain.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the unsigned, twice-folded, single-sheet original in BR’s hand in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives.

- 2

filled with loveHer edited letter of 2 September includes: “This is all rather dull: telling not one scrap of how I long for you, the whole loving miracle of you, my Heart. I don’t think you can really know how much I care. What’s worse is that I really can’t blame you for it, inarticulate creature that I am. Only my arms can tell you —” (BRACERS 113155).

- 3

your short letter that upset me nearly 4 weeks ago In Letter 71, BR wrote: “It was a great relief to get your letter today — the one yesterday was such a wretched scrap that it made me very unhappy, and I expected to remain so at least a week.” Colette identified the scrappy letter as one that began, “My Beloved, another dusty and footsore day.” It is undated and follows a letter dated 13 August, which, however, is equally scrappy and indeed begs forgiveness for “this scrap” (BRACERS 113148 and 113149).

- 4

your healthColette had written: “My doctor, by the way, thinks my inside needs attention (same old trouble)” (BRACERS 113155).

- 5

Gladys BR had said (Letter 87) that he wanted to give her a present and asked Colette’s help in choosing one.

- 6

I want both numbers of Journal of Philosophy back. It is not known which issues of this journal he had. His list of philosophical works read in prison doesn’t include any papers from The Journal of Philosophy, Psychology and Scientific Methods. Maybe it was used only to hide letters in.

- 7

quick and easier than a proper book Presumably because journal issues are lighter. They, too, could be used to carry correspondence.

- 8

arrival of Litvinov. I smile to him Early in 1918 Maxim Litvinov (1876–1951), a future Soviet foreign minister, obtained de facto recognition as Bolshevik Russia’s diplomatic representative to Britain. He and his staff were interned in Brixton for several weeks in retaliation for the arrest of Robert Bruce Lockhart, Litvinov’s London counterpart in Moscow, who stood accused with other British agents of conspiring to sabotage the revolution. (Britain had that summer launched a military intervention against the fledgling Bolshevik regime.) But a prisoner exchange was hastily negotiated, and both men were soon released and repatriated. BR and Litvinov would have acknowledged each other because they had met on at least three separate occasions (see Papers 14: lxxix–lxxx). Yet in May 1920, when BR had reached Stockholm on his intended trip to Russia, Litvinov forced him to cool his heels for several days awaiting a visa, while the Labour delegation (which BR was accompanying) went ahead (Papers 15: xxxix).

- 9

John Bull this week The article BR referred to was “In Prison for Debt; Scandalous Contrast in Treatment of Incarcerated”, John Bull, 7 Sept. 1918, p. 4. The exact quotation is: “This creature, Russell, who should be treated as the common criminal he is, rejoices in all the comforts of a home from home.” A small tradesman had been put in Brixton for the “non-payment of rates”. Feeling unfairly treated, he wrote to John Bull upon his release. The article describes BR’s cell as being “furnished like a gentleman’s room”. BR was waited on by a debtor, but not this complaining tradesman.

- 10

Mr. Bottomley Horatio Bottomley (1860–1933), journalist and owner of John Bull, a sensationalist weekly which was pro-war, anti-German, and also dealt in gossip. In 1922 Bottomley was found guilty of a war bonds swindle and sent to prison.

- 11

happened yesterday with Carr On 6 September Ottoline and Gladys Rinder travelled to the West Sussex home of Herbert Wildon Carr to discuss the fellowship plan.

- 12

Govt’s concession to Absolutists BR had been informed by Gladys Rinder (who was involved in the planning: see BRACERS 79631 and 79632) about a deputation to the Home Office led by Conservative peer Lord Parmoor and concerning recently introduced changes to the treatment of imprisoned “absolutist” C.O.s. All those incarcerated for more than two years already (about 700 in all) were transported in September 1918 from ordinary civil prisons to the Home Office camp in Wakefield, which had been occupied until recently by C.O.s willing to perform alternative service in lieu of actual imprisonment. The men moved into lockless cells, were able to fraternize freely, and enjoyed superior reading and writing privileges. But when the governor tried to compel his new charges to undertake prison work, they mounted an organized protest and were soon dispersed back to the regular prison system (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], pp. 300–3). The “concession”, such as it was, clearly fell short of what BR had urged after prison discipline was begrudgingly relaxed for C.O.s nine months previously. The real requirement was “the absolute exemption of all whose consciences can accept nothing less, and permission to do work of real national importance under conditions of freedom, instead of useless penal work under conditions which are still almost those of prison” (“The Government’s ‘Concessions’”, The Tribunal, no. 87 [13 Dec. 1917]: 2; 88 in Papers 14).

- 13

distinguished Comee. In Colette’s letter of 2 September 1918, she listed the members of the Experimental Theatre Committee as “Desmond <MacCarthy>, Massingham, Galsworthy, and Dennis (Bradley)” (BRACERS 113155). See the passage on the Theatre in Letter 62.

- 14

uncommercial travellers BR was making humorous use of the title of Charles Dickens’ collection of essays The Uncommercial Traveller (1861), in which Dickens took on the role of a traveller for the “great house of Human Interest Brothers”. Colette and her husband, Miles, were attempting to found a non-commercial theatre to put on experimental plays; they were still searching for how to accomplish the goal. Although their full vision was never revealed, they would have had to rent a cheap facility in London to put on the plays — away from commercial theatre. The plan may have come to fruition as the Everyman Theatre under the direction of Norman MacDermott. In his book Everymania (London: Society for Theatre Research, 1975), he noted that he met Miles in the summer of 1918: they rented a store in Bloomsbury, had a cabinetmaker build sets, and put on plays with actors “bored with West-End theatres” (p. 10) at a later, unknown time.

- 15

good parts to learn and do In Colette’s letter of 3 September 1918 (BRACERS 113156), she wrote that she was learning three roles: “Madge; a Schnitzler play; and an American one.” Arthur Schnitzler (1862–1931), was a Jewish Austrian playwright; his plays concern sexuality and anti-Semitism; he had experienced anti-Semitism first-hand. “Madge”was by Miles Malleson.

- 16

criticized “Madge” “Madge” was a play by Miles Malleson. Colette was to play Madge. In Letter 91 BR had written: “I have now read ‘Madge’.... It moved me, like everything Miles <Malleson> does. But it is not really good. It is dated, it depends wholly on its moral; as soon as people take that for granted, it has no point. And Madge’s sufferings are conventional.”

- 17

3 nuns … anything similar … brother smokes BR “smokes but one brand of tobacco, namely ‘Golden Mixture’ manufactured by Fribourg and Treyer, of which establishment he has been a customer since 1895”, reported his secretary in 1965 (BRACERS 37751). For his smoking a pipe, see Letter 2, note 13. In not specifying Golden Mixture, it appears that BR was making it easy for Colette to obtain almost any brand for him. He soon returned to Golden Mixture, as evidenced by his Fribourg and Treyer invoice of 1922 (BRACERS 130857).

- 18

your suit-case Presumably it was for emptying his cell of books, manuscripts and letters.

- 19

E. See Elizabethabove.

- 20

much worse time than I have In comparison with his imprisonment, BR was probably referring to Colette’s health problems (see Letter 95 and note 4).

Textual Notes

- a

when There is a hole in the sheet, but enough of a word survives to see it must have been “when”.

- b

<hole in paper> Missing is what must have been a short word, perhaps “all”.

- c

(Gladys has the other.) Inserted.

- d

travellers The middle four letters of this word are missing in a hole in the sheet, but “travellers” fits both the space and the context.

- e

“Madge” Quotation marks editorially supplied.

- f

Business. BR added a separate heading, “Mostly business”, in pencil at the top of page 2, which begins with the words “I will return your suit-case”.

- g

Cornish There is a hole in the sheet, but enough of the word exists to see it must have been “Cornish”.

57 Gordon Square

The London home of BR’s brother, Frank, 57 Gordon Square is in Bloomsbury. BR lived there, when he was in London, from August 1916 to April 1918, with the exception of January and part of February 1917.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Desmond MacCarthy

(Charles Otto) Desmond MacCarthy (1877–1952), literary critic, Cambridge Apostle, and a friend of BR’s since their Trinity College days in the 1890s. MacCarthy edited the Memoir (1910) of Lady John Russell.

Elizabeth Russell

Elizabeth Russell, born Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941), was a novelist who in 1891 married Graf von Arnim-Schlagenthin. She became known as “Elizabeth”, the name she used in publishing Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898), and she remained widely known as Elizabeth von Arnim, although the Library of Congress catalogues her as Mary Annette (Beauchamp), Countess von Arnim. She was a widow when she married BR’s brother, Frank, on 11 February 1916. The marriage was quickly in difficulty; she left it for good in March 1919, but they were never divorced and she remained Countess Russell (becoming Dowager Countess after Frank’s death in 1931).

Experimental Theatre

Colette first mentioned that she and Miles were trying to start an Experimental Theatre in a letter of 24 June 1918 (BRACERS 113135), indicating that Miles would earn a tiny income from it. About a month later, she wrote that Elizabeth Russell had subscribed generously to the Theatre and that £700 had been raised, but hundreds still had to be found (BRACERS 113146). A few days later she wrote that Captain Stephen Gordon, a north-country lawyer working for the government, was to be the honorary treasurer, noting that he had “put most of the drive into the whole thing” (BRACERS 113147). During August Colette was happy with her involvement with the Theatre (Letter 68). John Galsworthy came to tea to discuss the project (c.14 Aug., BRACERS 113149). On 2 September she listed the members of the Theatre committee as “Desmond <MacCarthy>, Massingham, Galsworthy, and Dennis (Bradley)” (BRACERS 113155). The following day she wrote that she was learning three parts (BRACERS 113156). In her memoirs, Colette wrote about the “Experimental Little Theatre” but dated it 1919 (After Ten Years [London: Cape, 1931], pp. 129–30). An “artistic” theatre did get founded in 1920 in Hampstead, and John Galsworthy was connected to that venture, The Everyman Theatre — he was part of a reading committee which chose the works to be performed (The Times, 9 Sept. 1919, p. 8). The Everyman Theatre was under the direction of Norman MacDermott. In his book Everymania (London: Society for Theatre Research, 1975), he noted that he met Miles in the summer of 1918: they rented a store in Bloomsbury, had a cabinetmaker build sets, and put on plays with actors “bored with West-End theatres” (p. 10). It is likely that the Everyman Theatre was an out-growth of the Experimental Theatre.

Fellowship Plan

Since the upper-age limit for compulsory military service had been increased to 50 in April 1918, BR was faced with the unnerving prospect of being conscripted after his release from Brixton. Early in his imprisonment he was already wondering about his “position when I emerge from here” (Letter 9). While his conviction was still under appeal, he had broached with Clifford Allen and Gilbert Murray the possibility of avoiding military service, not by asserting his conscientious objection to it, but by obtaining accreditation of his philosophical research as work of national importance (see note to Letter 24). The Pelham Committee, set up by the Board of Trade in March 1916, was responsible for the designation of essential occupations and recommending to the local tribunals, who adjudicated claims for exemption from military service, that C.O.s be considered for such positions. BR reasoned to Murray on 2 April that a dispensation to practise philosophy (as opposed to working outside his profession), would enable to him to “avoid prison without compromise” — i.e., of his political and moral opposition to conscription (BRACERS 52367). Although BR intended to withdraw from political work, he told Murray two days later, he would not promise to abstain from peace campaigning (BRACERS 52369). It should be noted that C.O.s who accepted alternative service in special Home Office camps were expressly prohibited from engaging in pacifist activities (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 231).

BR was far from sanguine about the prospect of success before a local tribunal. But he came to think (by early June) that his chances would be improved if his academic supporters interceded directly with the Minister of National Service, Sir Auckland Geddes. In addition, he calculated that such entreaties would be more effective if those acting on his behalf could secure and even endow a fellowship for him and thereby have “something definite to put before Geddes” (Letter 12; see also Letters 15 and 19). BR definitely wanted to rededicate himself to philosophy and would have welcomed a new source of income from academic employment (see Letter 22). But the “financial aspect was quite secondary”, he reminded Frank on 24 June (Letter 27); he was interested in the fellowship plan primarily as a safeguard against being called up, for teachers over 45 were not subject to the provisions of the recently amended Military Service Act. In the same letter, however, BR told his brother that “I wish it <the plan> dropped” on account of reservations expressed to him in person by Wildon Carr and A.N. Whitehead (see also Letter 31), two philosophers whom he respected but who seemed to doubt whether BR’s financial needs were as great as they appeared (see note to Letter 102).

Yet BR’s retreat was only temporary. On 8 August, he expressed to Ottoline a renewed interest in the initiative, and a few days later, she, her husband and Gladys Rinder met in London to discuss the matter. As Ottoline reported to BR, “we all felt that it was useless to wait for others to start and we decided that P. and I should go and see Gilbert M. and try and get him to work it with the Philosophers” (11 Aug. 1918, BRACERS 114754). BR probably wanted Murray to spearhead this lobbying (see also Letters 65 and 70) because of his political respectability and prior success in persuading professional philosophers to back an appeal to the Home Secretary for BR’s sentence to be served in the first division (see Letter 6). Murray did play a leading role but not until early the following month, when BR was anxious for the fellowship plan to succeed as his release date neared. The scheme finally gathered momentum after a meeting between Ottoline, Rinder and Carr on 6 September 1918, at which the philosopher and educationist T. Percy Nunn, another academic supporter of BR, was also present. Within a few days Murray had drafted a statement with an appeal for funds, which was endorsed by Carr, Whitehead, Nunn, Samuel Alexander, Bernard Bosanquet, G. Dawes Hicks, A.E. Taylor and James Ward. This memorial was then circulated in confidence to philosophers and others, but only after BR’s release from Brixton. (Financial pledges had already been made by a few of BR’s friends and admirers, notably Lucy Silcox and Siegfried Sassoon.) BR’s solicitor, J.J. Withers, became treasurer of this endowment fund, the goal of which was to provide BR with £150 or £200 per annum over three years. On 30 August BR had confessed to Ottoline that he did not want an academic position “very far from London” (Letter 89) and reiterated this desire in a message to Murray communicated by Rinder (Letter 97). On 6 September Rinder (BRACERS 79633) hinted that she already knew where the appointment would be, but there are no other indications that a particular establishment had been decided upon. Ultimately, no affiliation was contemplated for BR, so the memorial stated, because “in the present state of public feeling no ordinary university institution is likely to be willing to employ him as a teacher” (copy in BRACERS 56750). The circular talked instead of a “special Lectureship”, and the £100 BR received from the fund early in 1919 was explicitly issued as payment for lectures (on “The Analysis of Mind”; see syllabus, in Papers 9: App. III.1) that he would deliver that spring. BR’s solicitor also informed him that provision existed to pay him a further £100 for an autumn lecture course (see syllabus, ibid.: App. III.2), and Withers anticipated that these arrangements might “last two or three years” (2 Jan. 1919, BRACERS 81764). BR had already obtained a £50 gift from the fund in November 1918. Somewhat ironically, the critical importance of a teaching component to the fellowship plan — as insurance against conscription — was reduced by the authorities hesitating to hound BR any further after his imprisonment, and all but nullified by the end of the war a few weeks later. (There were no fresh call-ups, but the last of the C.O.s already in prison were not released until August 1919, and conscription remained in effect until April 1920.)

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

H. Wildon Carr

Herbert Wildon Carr (1857–1931), Professor of Philosophy at King’s College, London, from 1918 and Visiting Professor at the University of Southern California from 1925. Carr came to philosophy late in life after a lucrative career as a stockbroker. His philosophy was an idiosyncratic amalgam of Bergsonian vitalism and Leibnizian monadology, which, he thought, was supported by modern biology and the theory of relativity. He wrote books on Bergson and Leibniz at opposite ends of his philosophical career and a book on relativity in the middle. His philosophy would have made him an unlikely ally of BR’s, but it was Carr who organized BR’s two courses of public lectures, on philosophy of mathematics and the philosophy of logical atomism, which brought BR back to philosophy and improved his finances in 1917–18. Carr had great administrative talents, which he employed also on behalf of the Aristotelian Society during his long association with it. He was its president in 1916–18 and continued to edit its Proceedings until 1929.

H.W. Massingham

H.W. Massingham (1860–1924), radical journalist and founding editor in 1907 of The Nation, a publication which superseded The Speaker and soon became Britain’s foremost Liberal weekly. Almost immediately the editor of the new periodical started to host a weekly luncheon (usually at the National Liberal Club), which became a vital forum for the exchange of “New Liberal” ideas and strategies between like-minded politicians, publicists and intellectuals (see Alfred F. Havighurst, Radical Journalist: H.W. Massingham, 1860–1924 [Cambridge: U. P., 1974], pp. 152–3). On 4 August 1914, BR attended a particularly significant Nation lunch, at which Massingham appeared still to be in favour of British neutrality (see Papers 13: 6) — which had actually ended at the stroke of midnight. By the next day, however, Massingham (like many Radical critics of Britain’s pre-war diplomacy) had come to accept the case for military intervention, a position he maintained (not without misgivings) for the next two years. Massingham was still at the helm of the Nation when it merged with the more literary-minded Athenaeum in 1921; he finally relinquished editorial control two years later. In 1918 he served on Miles and Constance Malleson’s Experimental Theatre Committee.

Miles Malleson

Miles Malleson (1888–1969), actor and playwright, was born in Croydon, Surrey, the son of Edmund and Myrrha Malleson. He married his first wife, a fellow actor, Lady Constance Annesley (stage name, Colette O’Niel), in 1915. They had met at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts). Their marriage was an “open” one. In 1914 Miles enlisted in the City of London Fusiliers and was sent to Malta. He became ill and was discharged, unfit for further service. He became active in the No-Conscription Fellowship and wrote anti-war stage plays as well as a pamphlet, Cranks and Commonsense (1916). In the 1930s he began to write for the screen and act in films, in which he became a very well-known character actor, as well as continuing his stage career at the Old Vic in London. He married three times: his second marriage was to Joan Billson, a physician (married 1923, divorced 1940), with whom he had two children; his third wife was Tatiana Lieven, an actress (married 1946). He died in London in March 1969.

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

The Studio

The accommodation BR and Colette rented on the ground floor at 5 Fitzroy Street, just off Howland Street, London W1. “It had a top light, a gas fire and ring. A water tap and lavatory in the outside passage were shared with a cobbler whose workshop adjoined” (Colette’s annotation at BRACERS 113087). It was ready to occupy in November 1917.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.