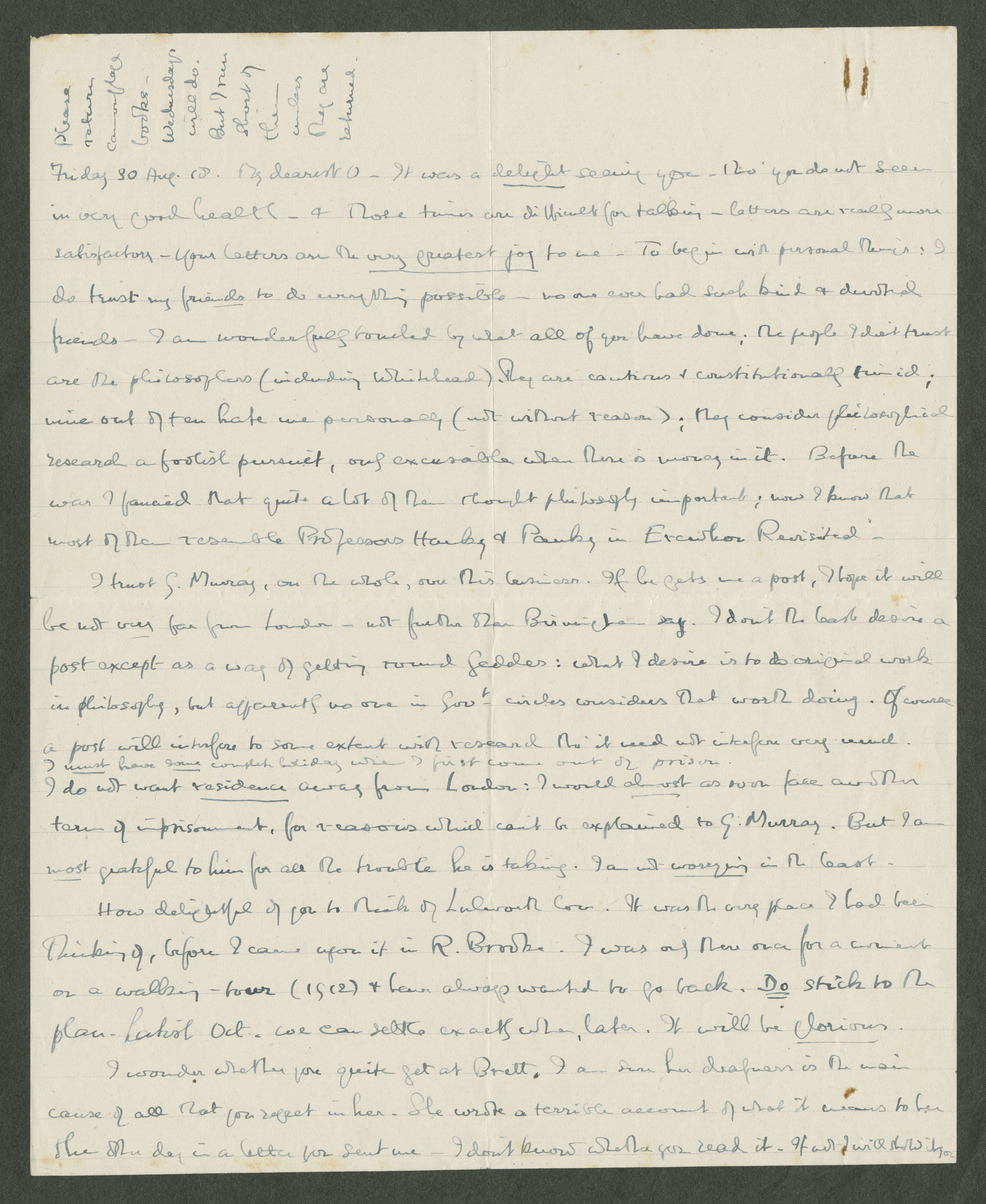

Brixton Letter 89

BR to Ottoline Morrell

August 30, 1918

- ALS

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-89Auto. 2: 91-2

BRACERS 18690

<Brixton Prison>1

Friday 30 Aug. 18.

My dearest O

It was a delight seeing you — tho’ you do not seem in very good health — and those times are difficult for talking — letters are really more satisfactory. Your letters are the very greatest joy to me. To begin with personal things: I do trust my friends to do everything possible — no one ever had such kind and devoted friends. I am wonderfully touched by what all of you have done; the people I don’t trust are the philosophers (including Whitehead).2 They are cautious and constitutionally timid; nine out of ten hate me personally (not without reason); they consider philosophical research a foolish pursuit, only excusable when there is money in it. Before the war I fancied that quite a lot of them thought philosophy important; now I know that most of them resemble Professors Hanky and Panky in Erewhon Revisited.3

I trust G. Murray, on the whole, over this business.4 If he gets me a post, I hope it will be not very far from London — not further than Birmingham say. I don’t the least desire a post except as a way of getting round Geddes: what I desire is to do original work in philosophy, but apparently no one in Govt. circles considers that worth doing. Of course a post will interfere to some extent with research tho’ it need not interfere very much. I must have some complete holiday when I first come out of prison.a I do not want residence away from London: I would almost as soon face another term of imprisonment, for reasons which can’t be explained to G. Murray. But I am most grateful to him for all the trouble he is taking. I am not worrying in the least.

How delightful of you to think of Lulworth Cove.5 It was the very place I had been thinking of, before I came upon it in R. Brooke.6 I was only there once for a moment on a walking-tour (1912)7 and have always wanted to go back. Do stick to the plan. Latish Oct. We can settle exactly when, later. It will be glorious.

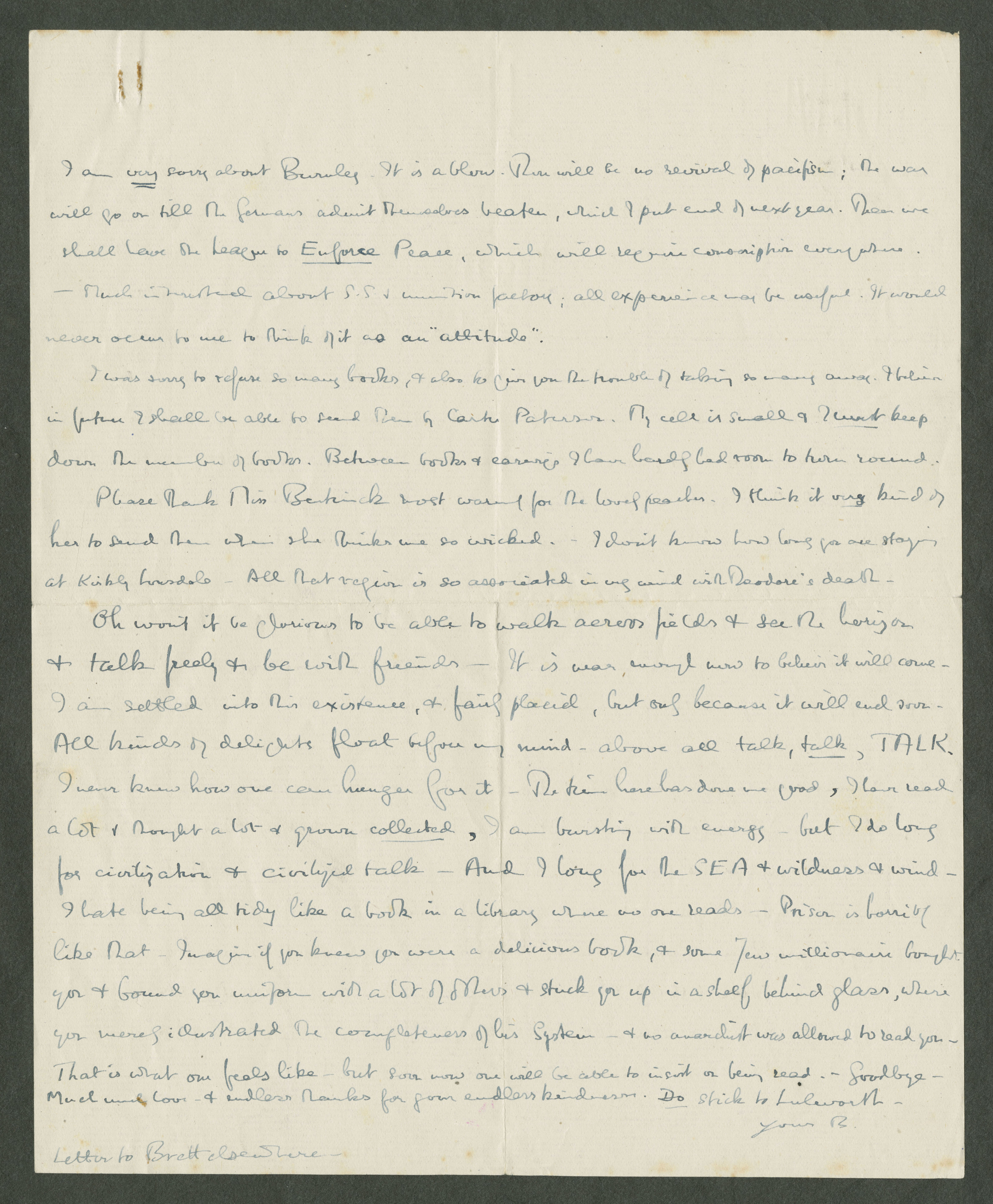

I wonder whether you quite get at Brett. I am sure her deafness is the main cause of all that you regret in her. She wrote a terrible account8 of what it means to her the other day in a letter you sent me — I don’t know whether you read it. If not I will show it you. I am very sorry about Burnley.9 It is a blow. There will be no revival of pacifism; the war will go on till the Germans admit themselves beaten, which I put end of next year.10 Then we shall have the League to Enforce Peace,11 which will require conscription everywhere. — Much interested about S.S. and munition factory; all experience may be useful. It would never occur to me to think of it as an “attitude”.12

I was sorry to refuse so many books, and also to give you the trouble of taking so many away. I believe in future I shall be able to send them by Carter Paterson.13 My cell is small and I must keep down the number of books. Between books and earwigs I have hardly had room to turn round.

Please thank Miss Bentinck14 most warmly for the lovely peaches. I think it very kind of her to send them when she thinks me so wicked. — I don’t know how long you are staying at Kirkby Lonsdale. All that region is so associated in my mind with Theodore’s death.15

Oh won’t it be glorious to be able to walk across fields and see the horizon and talk freely and be with friends. It is near enough now to believe it will come. I am settled into this existence, and fairly placid, but only because it will end soon. All kinds of delights float before my mind — above all talk, talk, TALK. I never knew how one can hunger for it. The time here has done me good, I have read a lot and thought a lot and grown collected, I am bursting with energy — but I do long for civilization and civilized talk. And I long for the SEA and wildness and wind. I hate being all tidy like a book in a library where no one reads. Prison is horribly like that. Imagine if you knew you were a delicious book, and some Jew millionaire16 bought you and bound you uniform with a lot of others and stuck you up in a shelf behind glass, where you merely illustrated the completeness of his System — and no anarchist was allowed to read you. That is what one feels like — but soon now one will be able to insist on being read. — Goodbye. Much much love — and endless thanks for your endless kindness. Do stick to Lulworth.

Your

B.

Letter to Brett17 elsewhere.

Please return camouflage books18, b — Wednesday will do. But I run short of them unless they are returned.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the initialled, twice-folded, single-sheet original in BR’s hand in the Russell Archives. This letter and Letter 88 are covered by a note on the latter in pencil in Elizabeth Trevelyan’s hand: “In 1923 these letters fell out of a book lent to B.R. when he was in prison in 1918.” The present letter was published in BR’s Autobiography, 2: 91–2. See also note 18.

- 2

Whitehead There may be a touch of paranoia in BR’s extending his suspicions to his long-time friend and collaborator, but it is more likely that he wanted to make sure that Ottoline did not take even Whitehead’s support for granted. Whitehead supported the war and in March had lost a son in the fighting; this made relations painful for both parties. In fact, Whitehead opposed BR’s dismissal from Trinity College in 1916 (see his To the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge) and was prominent in efforts to have him reinstated after the war was over.

- 3

Professors Hanky and Panky in Erewhon RevisitedSamuel Butler, Erewhon RevisitedTwenty Years Later, Both by the Original Discoverer of the Country and by His Son (London: Grant Richards, 1901). In this satire of religion of which BR was a fan, Hanky and Panky, Royal Professors (respectively) of Worldly and Unworldly Wisdom, were the scheming sophists of a new cult of “Sunchildism”. This had spread through Erewhon after the object of devotion (and the protagonist of Butler’s earlier novel of that name) had escaped from the fictional country by balloon twenty years previously.

- 4

I trust G. Murray ... over this business I.e., the business of bringing the fellowship plan to fruition.

- 5

Lulworth Cove Ottoline and BR intended to stay at this picturesque Dorset location in late October. While in prison, BR keenly anticipated this visit to the coast (see Letter 94) and told Ottoline after his release that he was “counting on Lulworth” (3 Oct. 1918, BRACERS 18698). But she dropped out of the planned trip on 7 October (BRACERS 114761), and BR ended up going to Lulworth with Colette instead, on 16–19 October. BR and Littlewood rented a nearby farm for the summer of 1919: “The place was extraordinarily beautiful, with wide views along the coast” (Auto. 2: 96).

- 6

R. Brooke Rupert Brooke wrote “Sonnet Reversed” at Lulworth Cove. More importantly for him and BR, he discovered that Lulworth was where John Keats last stepped on English soil.

- 7

a walking-tour (1912) BR went by himself in March 1912, armed with pocket volumes of Shakespeare, Blake, Keats, and probably The Oxford Book of English Verse (Monk 1: 254; Clark, p. 173).

- 8

Brett … her deafness … terrible account In her letter of 25 August Ottoline expressed a measure of irritation and contempt for the Bloomsbury artist Dorothy Brett. She had suffered dramatic hearing-loss after undergoing surgery for appendicitis in 1902 and experienced since then a steady worsening of the condition. In the “terrible account” to which Letter 88 was written in a reply never received by Brett, she despairingly likened her condition to BR’s imprisonment: “I feel that prison must in some ways be curiously like the life I lead. I rather wonder which is the worst — prison I think because with an effort I can be included in a small way in human life — you are more cut off. But can you imagine what it means to see Life revolving round you — see people talking and laughing, quite meaninglessly! Like looking through a shop window or a restaurant window. It is all so hideous I sometimes wonder how I can go on” (26 Aug. 1918, BRACERS 75044).

- 9

I am very sorry about Burnley. On 11 August 1918 Ottoline reported to BR that the Burnley Liberal Association was “still undecided” (BRACERS 114754) as to whether Philip Morrell would again be its candidate in the Lancashire borough constituency he had narrowly won in December 1910. Only two weeks later, however, she was “afraid Burnley is hopeless” (25 Aug., BRACERS 114756). Ottoline was responding to attacks on her husband’s anti-war dissent in the Burnley News, the local Liberal newspaper, recently acquired by a new owner. Ultimately, the Liberal nomination was given to John Grey, a local industrialist, town councillor and justice of the peace. Although Grey backed the Lloyd George Coalition, it was the Conservative candidate who would obtain its official backing in the so-called Coupon Election of 14 December, which in Burnley, in a three-way contest, resulted in victory for Labour.

- 10

war will go on … end of next year In light of significant strategic gains made by the Allies during his imprisonment (see Letters 30, 44 and 60), BR’s forecasting about the war’s likely duration had become slightly more optimistic since his forlorn prediction to Gladys Rinder of its continuation “till Germany is as utterly defeated as France was in 1814, and that that will take about another ten years” (Letter 20). Yet BR clearly underestimated the rapidity with which German military resistance was crumbling on the Western Front. The final Allied victory was achieved extremely quickly after Germany’s previously impregnable Hindenburg Line of defences was breached at the end of September. “Was anything ever so dramatic as the collapse of the ‘enemy’”, he asked Ottoline on 9 November 1918 (BRACERS 18703).

- 11

League to Enforce Peace This pressure group was founded in June 1915 by American internationalists influenced by proposals for war prevention formulated by the Bryce Group of British politicians and intellectuals (notable among whom was BR’s friend Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson). Yet pacifists on both sides of the Atlantic disliked the coercive implications of the scheme, and BR’s discomfort is reflected in the emphasis on “Enforce”. In his many subsequent discussions of world government, however, BR always accepted the need for a machinery of compulsion and, moreover, that a viable international authority must exercise monopoly control of the major weapons of war.

- 12

S.S. and munition factory … as an “attitude”Siegfried Sassoon did not follow through on this plan to go “as a common workman into a munition factory at Sheffield” (Ottoline to BR, 25 Aug. 1918, BRACERS 114756), although he had also told others that he wanted to learn about the world of labour by going “as an ordinary worker in some works in a large town” (Jean Moorcroft Wilson, Siegfried Sassoon: Soldier, Poet, Lover, Friend [New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2014], p. 319). Although BR clearly regarded the soldier-poet’s intentions as sincere, Sassoon was afraid, he told Ottoline, that his wish would be scorned as an “Attitude” (i.e., a pose) (BRACERS 114756). Despite Sassoon not fulfilling the desire to which Letter 85 refers, he was soon interviewed by Winston Churchill (probably at Edward Marsh’s behest) for a quite different role in the defence establishment, at the Ministry of Munitions (ibid., p. 325). But he never assumed a position of this kind either.

- 13

Carter Paterson Movers. This road haulage company was established in 1860 and headquartered in London.

- 14

Miss Bentinck Violet Bentinck (1864–1932), Ottoline’s spinster cousin, with whom she had left her daughter, Julian, before travelling to Kirkby Lonsdale. She “is very nice about you”, Ottoline told BR on 27 August 1918 (BRACERS 114756).

- 15

how long you are staying at Kirkby Lonsdale … region is so associated … with Theodore’s deathOttoline spent the week of 29 August to 4 September 1918 at Underley Hall, just outside Kirkby Lonsdale, where her brother Henry Cavendish-Bentinck, the Conservative politician, lived in the country house inherited by his wife, Lady Olivia. Thirteen years previously, one of BR’s closest Cambridge friends, Theodore Llewelyn Davies (1871–1905), had drowned in a swimming accident near this small town in the southern Lake District, where his father was vicar. Distraught himself, for several weeks BR comforted Theodore’s grief-stricken brother, Crompton, to whom BR was no less attached. Later, sometime after Crompton married in 1910, he distanced himself from BR for many years, so the latter believed, because “I had become so much associated with his suffering after Theodore’s death, that for a long time he found my presence painful” (Auto. 1: 58). It is noteworthy that the Brixton letters make no mention of Crompton, even as a visitor.

- 16

Jew millionaire This is perhaps the most egregious example of casual anti-Semitic stereotyping that occasionally appeared in BR’s personal letters until Hitler’s rise to power. Yet BR was “in no sense an anti-Semite”, concludes Ronald Clark’s by no means exculpatory assessment of his subject’s lapses in this regard (The Life of Bertrand Russell [London: Cape and Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1975], p. 380). BR never tolerated institutional or informal discrimination against any racial, ethnic or national group, and as a powerful public voice of tolerance he was held in high esteem by world Jewry.

- 17

Letter to Brett I.e., Letter 88.

- 18

camouflage books Studies of BR and even Ottoline Morrell (Morrell, Memoirs 2: 252–3; Vellacott, p. 237; Seymour, p. 296; Papers 14: 412; Monk, 1: 526; SLBR 2: 158) remark on the way he smuggled letters out of prison in 1918. Letters were hidden in the uncut pages of books and journals. Yet concealment was sometimes too good. In 1923 the present letter to Ottoline and another of the same date to Dorothy Brett (Letter 88) fell out of a book that was meant for the former. The book belonged to Robert and Elizabeth Trevelyan, and the letters were returned to BR with a note in Elizabeth Trevelyan’s hand. BR printed both letters in his Autobiography.

Textual Notes

- a

I must have … prison. Inserted.

- b

Please return camouflage books In his Autobiography’s printing of this letter (2: 92), the sentence reads: “Please return commonplace books”, although BR is not known to have used a commonplace book in Brixton. The letter was typed from the original by Edith Russell, who had plenty of opportunity to query the author on questionable passages, but she or they missed seeing that the word was “camouflage”.

A.N. Whitehead

Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947), Cambridge-educated mathematician and philosopher. From 1884 to 1910 he was a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, and lecturer in mathematics there; from 1911 to 1924 he taught in London, first at University College and then at the Imperial College of Science and Technology; in 1924 he took up a professorship in philosophy at Harvard and spent the rest of his life in America. BR took mathematics courses with him as an undergraduate, which led to a lifelong friendship. Whitehead’s first major work was A Treatise on Universal Algebra (1898), which treated selected mathematical theories as “systems of symbolic reasoning”. Like BR’s The Principles of Mathematics (1903), it was intended as the first of two volumes; but in 1900 he and BR discovered Giuseppe Peano’s work in symbolic logic, and each decided to set aside his projected second volume to work together on a more comprehensive treatment of mathematics using Peano’s methods. The result was the three volumes of Principia Mathematica (1910–13), which occupied the pair for over a decade. After Principia was published, Whitehead’s interests, like BR’s, turned to the empirical sciences and, finally, after his move to America, to pure metaphysics. See Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: the Man and His Work, 2 vols. (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins U. P., 1985–90).

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.

David Lloyd George

Through ruthless political intrigue, David Lloyd George (1863–1945) emerged in December 1916 as the Liberal Prime Minister of a new and Conservative-dominated wartime Coalition Government. The “Welsh wizard” remained in that office for the first four years of the peace after a resounding triumph in the notorious “Coupon” general election of December 1918. BR despised the war leadership of Lloyd George as a betrayal of his Radical past as a “pro-Boer” critic of Britain’s South African War and as a champion of New Liberal social and fiscal reforms enacted before August 1914. BR was especially appalled by the Prime Minister’s stubborn insistence that the war be fought to a “knock-out” and by his punitive treatment of imprisoned C.O.s. For the latter policy, as BR angrily chastised Lloyd George at their only wartime meeting, “his name would go down to history with infamy” (Auto. 2: 24).

Dorothy Brett

Dorothy Eugénie Brett (1883–1977), painter, benefitted from the patronage of Ottoline Morrell, who set up a studio for her at Garsington Manor. She lived there for three years (1916–19), becoming friends with J. Middleton Murry and Katherine Mansfield, among other visitors to the Morrells’ country home. Brett was the daughter of Liberal politician and courtier Viscount Esher. Notwithstanding her generous encouragement of Brett’s work, Ottoline could become impatient with her guest’s acute deafness, about which BR wrote compassionately in Letter 88. BR’s note below that letter in Auto. 2: 93 reads: “The lady to whom the above letter is addressed was a daughter of Lord Esher but was known to all her friends by her family name of Brett. At the time when I wrote the above letter, she was spending most of her time at Garsington with the Morrells. She went later to New Mexico in the wake of D.H. Lawrence.”

Fellowship Plan

Since the upper-age limit for compulsory military service had been increased to 50 in April 1918, BR was faced with the unnerving prospect of being conscripted after his release from Brixton. Early in his imprisonment he was already wondering about his “position when I emerge from here” (Letter 9). While his conviction was still under appeal, he had broached with Clifford Allen and Gilbert Murray the possibility of avoiding military service, not by asserting his conscientious objection to it, but by obtaining accreditation of his philosophical research as work of national importance (see note to Letter 24). The Pelham Committee, set up by the Board of Trade in March 1916, was responsible for the designation of essential occupations and recommending to the local tribunals, who adjudicated claims for exemption from military service, that C.O.s be considered for such positions. BR reasoned to Murray on 2 April that a dispensation to practise philosophy (as opposed to working outside his profession), would enable to him to “avoid prison without compromise” — i.e., of his political and moral opposition to conscription (BRACERS 52367). Although BR intended to withdraw from political work, he told Murray two days later, he would not promise to abstain from peace campaigning (BRACERS 52369). It should be noted that C.O.s who accepted alternative service in special Home Office camps were expressly prohibited from engaging in pacifist activities (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 231).

BR was far from sanguine about the prospect of success before a local tribunal. But he came to think (by early June) that his chances would be improved if his academic supporters interceded directly with the Minister of National Service, Sir Auckland Geddes. In addition, he calculated that such entreaties would be more effective if those acting on his behalf could secure and even endow a fellowship for him and thereby have “something definite to put before Geddes” (Letter 12; see also Letters 15 and 19). BR definitely wanted to rededicate himself to philosophy and would have welcomed a new source of income from academic employment (see Letter 22). But the “financial aspect was quite secondary”, he reminded Frank on 24 June (Letter 27); he was interested in the fellowship plan primarily as a safeguard against being called up, for teachers over 45 were not subject to the provisions of the recently amended Military Service Act. In the same letter, however, BR told his brother that “I wish it <the plan> dropped” on account of reservations expressed to him in person by Wildon Carr and A.N. Whitehead (see also Letter 31), two philosophers whom he respected but who seemed to doubt whether BR’s financial needs were as great as they appeared (see note to Letter 102).

Yet BR’s retreat was only temporary. On 8 August, he expressed to Ottoline a renewed interest in the initiative, and a few days later, she, her husband and Gladys Rinder met in London to discuss the matter. As Ottoline reported to BR, “we all felt that it was useless to wait for others to start and we decided that P. and I should go and see Gilbert M. and try and get him to work it with the Philosophers” (11 Aug. 1918, BRACERS 114754). BR probably wanted Murray to spearhead this lobbying (see also Letters 65 and 70) because of his political respectability and prior success in persuading professional philosophers to back an appeal to the Home Secretary for BR’s sentence to be served in the first division (see Letter 6). Murray did play a leading role but not until early the following month, when BR was anxious for the fellowship plan to succeed as his release date neared. The scheme finally gathered momentum after a meeting between Ottoline, Rinder and Carr on 6 September 1918, at which the philosopher and educationist T. Percy Nunn, another academic supporter of BR, was also present. Within a few days Murray had drafted a statement with an appeal for funds, which was endorsed by Carr, Whitehead, Nunn, Samuel Alexander, Bernard Bosanquet, G. Dawes Hicks, A.E. Taylor and James Ward. This memorial was then circulated in confidence to philosophers and others, but only after BR’s release from Brixton. (Financial pledges had already been made by a few of BR’s friends and admirers, notably Lucy Silcox and Siegfried Sassoon.) BR’s solicitor, J.J. Withers, became treasurer of this endowment fund, the goal of which was to provide BR with £150 or £200 per annum over three years. On 30 August BR had confessed to Ottoline that he did not want an academic position “very far from London” (Letter 89) and reiterated this desire in a message to Murray communicated by Rinder (Letter 97). On 6 September Rinder (BRACERS 79633) hinted that she already knew where the appointment would be, but there are no other indications that a particular establishment had been decided upon. Ultimately, no affiliation was contemplated for BR, so the memorial stated, because “in the present state of public feeling no ordinary university institution is likely to be willing to employ him as a teacher” (copy in BRACERS 56750). The circular talked instead of a “special Lectureship”, and the £100 BR received from the fund early in 1919 was explicitly issued as payment for lectures (on “The Analysis of Mind”; see syllabus, in Papers 9: App. III.1) that he would deliver that spring. BR’s solicitor also informed him that provision existed to pay him a further £100 for an autumn lecture course (see syllabus, ibid.: App. III.2), and Withers anticipated that these arrangements might “last two or three years” (2 Jan. 1919, BRACERS 81764). BR had already obtained a £50 gift from the fund in November 1918. Somewhat ironically, the critical importance of a teaching component to the fellowship plan — as insurance against conscription — was reduced by the authorities hesitating to hound BR any further after his imprisonment, and all but nullified by the end of the war a few weeks later. (There were no fresh call-ups, but the last of the C.O.s already in prison were not released until August 1919, and conscription remained in effect until April 1920.)

G. Lowes Dickinson

Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson (1862–1932) was a Fellow and Lecturer of King’s College, Cambridge, where he had moved inside the same tight circle of friends as the undergraduate BR. According to BR, “Goldie” (as he was fondly known to intimates) “inspired affection by his gentleness and pathos” (Auto. 1: 63). As a scholar, his interests ranged across politics, history and philosophy. Also a passionate internationalist, Dickinson was an energetic promoter of future war prevention by a League to Enforce Peace. And he was a poet: BR copied three of his poems into “All the Poems That We Have Most Enjoyed Together”: Bertrand Russell’s Commonplace Book, ed. K. Blackwell (Hamilton, ON: McMaster U. Library P., 2018), pp. 8–13.

Gilbert Murray

Gilbert Murray (1866–1957), distinguished classical scholar and dedicated liberal internationalist. He was Regius Professor of Greek at Oxford, 1908–36, and chair of the League of Nations Union, 1923–36. He and BR enjoyed a long and close friendship that was ruptured temporarily by bitter disagreement over the First World War. After Murray published The Foreign Policy of Sir Edward Grey, 1906–1915, in defence of Britain’s pre-war diplomacy, BR responded with a detailed critique, The Policy of the Entente, 1904–1914: a Reply to Professor Gilbert Murray (37 in Papers 13). Yet Murray still took the lead in campaigning to get BR’s sentence reassigned from the second to the first division and (later) in leading an appeal for professional and financial backing of an academic appointment for BR upon his release (the “fellowship plan”, which looms large in his prison correspondence). BR was still thankful for Murray’s exertions some 40 years later. See his portrait of Murray, “A Fifty-Six Year Friendship”, in Murray, An Unfinished Autobiography with Contributions by His Friends, ed. Jean Smith and Arnold Toynbee (London: Allen & Unwin, 1960).

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

J.E. Littlewood

John Edensor Littlewood (1885–1977), mathematician. In 1908 he became a fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, and remained one for the rest of his life. In 1910 he succeeded Whitehead as college lecturer in mathematics and began his extraordinarily fruitful, 35-year collaboration with G.H. Hardy. During the First World War he worked on ballistics for the British Army. He and BR were to share Newlands farm, near Lulworth, during the summer of 1919. Littlewood had two children, Philip and Ann Streatfeild, with the wife of Dr. Raymond Streatfeild.

Philip Morrell

Philip Morrell, Ottoline’s husband (1870–1943), whom she had married in 1902 and with whom, four years later, she had twins — Julian, and her brother, Hugh, who died in infancy. The Morrells were wealthy Oxfordshire brewers, although Philip’s father was a solicitor. He won the Oxfordshire seat of Henley for the Liberal Party in 1906 but held this Conservative stronghold only until the next general election, four years later. For the second general election of 1910 he ran successfully for the Liberals in the Lancashire manufacturing town of Burnley. But Morrell’s unpopular anti-war views later cost him the backing of the local Liberal Association, and his failure to regain the party’s nomination for the post-war election of 1918 (see Letter 89) effectively ended his short political career. Unlike many other Liberal critics of British war policy (including BR), Morrell did not transfer his political allegiance to the Labour Party. Although Ottoline and her husband generally tolerated each other’s extra-marital affairs, a family crisis ensued when in 1917 Philip impregnated both his wife’s maid and his secretary (see Letter 48).

Rupert Brooke

Rupert Chawner Brooke (1887–1915), poet and soldier, became a tragic symbol of a generation doomed by war after he died from sepsis en route to the Gallipoli theatre. Although BR had previously expressed a dislike, even loathing, of Brooke in letters to Ottoline, he too placed him in this tragic posthumous light. Rupert “haunts one always”, he wrote Ottoline shortly after the poet’s death in April 1915, and (five months later) “one is made so terribly aware of the waste when one is here [Trinity College]…. Rupert Brooke’s death brought it home to me” (BRACERS 18431, 18435: see also Letter 85). Brooke had become acquainted with BR and members of the Bloomsbury Group in pre-war Cambridge. BR was an examiner of Brooke’s King’s College fellowship dissertation (later published as John Webster and the Elizabethan Drama [1916]), with which he was pleasantly and surprisingly impressed. “It is astonishingly well-written, vigorous, fertile, full of life”, he reported to Ottoline in February 1912 (BRACERS 17447). After the outbreak of war Brooke obtained a commission in a naval reserve unit attached to a military combat battalion; his war poetry captures the patriotic idealism that compelled so many young men to enlist.

Siegfried Sassoon

Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967), soldier awarded the MC and anti-war poet. Ottoline had befriended him in 1916, and the following year, when Sassoon refused to return to his regiment after being wounded, she and BR helped publicize this protest, which probably saved him from a court martial. BR even assisted Sassoon in revising his famous anti-war statement, which was read to the House of Commons by a Liberal M.P. on 30 July 1917. Sassoon’s actions were an embarrassment to the authorities, for he was well known as both a poet and a war hero. Unable to hush the case up, the government acted with unexpected subtlety and declared Sassoon to be suffering from shell-shock and sent him to Craiglockhart War Hospital for Officers, near Edinburgh. After a period of recuperation in Scotland overseen by military psychiatrist Capt. W.H.R. Rivers, Sassoon decided to return to the Front (see Jean Moorcroft Wilson, Siegfried Sassoon: Soldier, Poet, Lover, Friend [New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2014]). He was again wounded in July 1918 and was convalescing in Britain during some of BR’s imprisonment. Although each admired the other’s stand on the war, BR and Sassoon were never close in later years. Yet Sassoon did pledge £50 to the fellowship plan fund (see BRACERS 114758), and decades later he donated a manuscript in support of BR’s International War Crimes Tribunal (see BRACERS 79066).

Sir Auckland Geddes

Sir Auckland Geddes (1879–1954; 1st Baron Geddes, 1942) was returned unopposed as Conservative M.P. for Basingstoke in a by-election held in October 1917. Before this entry into civilian public life, he held the rank of Brigadier-General as director of recruiting at the War Office. He was an ardent champion of conscription even in peacetime and had a long-standing interest in the military, which he expressed before the war as a volunteer medical officer in the British Army Reserve. He had studied medicine and was Professor of Anatomy at McGill University, Montreal, when the outbreak of war prompted an immediate return to Britain in order to enlist. After a riding accident rendered Geddes unfit for front-line duties, he became a staff officer in France with a remit covering the supply and deployment of troops. He performed similar duties at the War Office until his appointment in August 1917 as a Minister of National Service with broad powers over both military recruitment and civilian labour. Geddes held two more Cabinet positions in Lloyd George’s post-war Coalition Government before his appointment in 1920 as British Ambassador to the United States. After returning from Washington on health grounds three years later, Geddes embarked upon a successful business career, becoming chairman in 1925 of the Rio Tinto mining company. See Oxford DNB.

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.