Brixton Letter 87

BR to Constance Malleson

August 29, 1918

- ALS

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-87

BRACERS 19354

<Brixton Prison>1

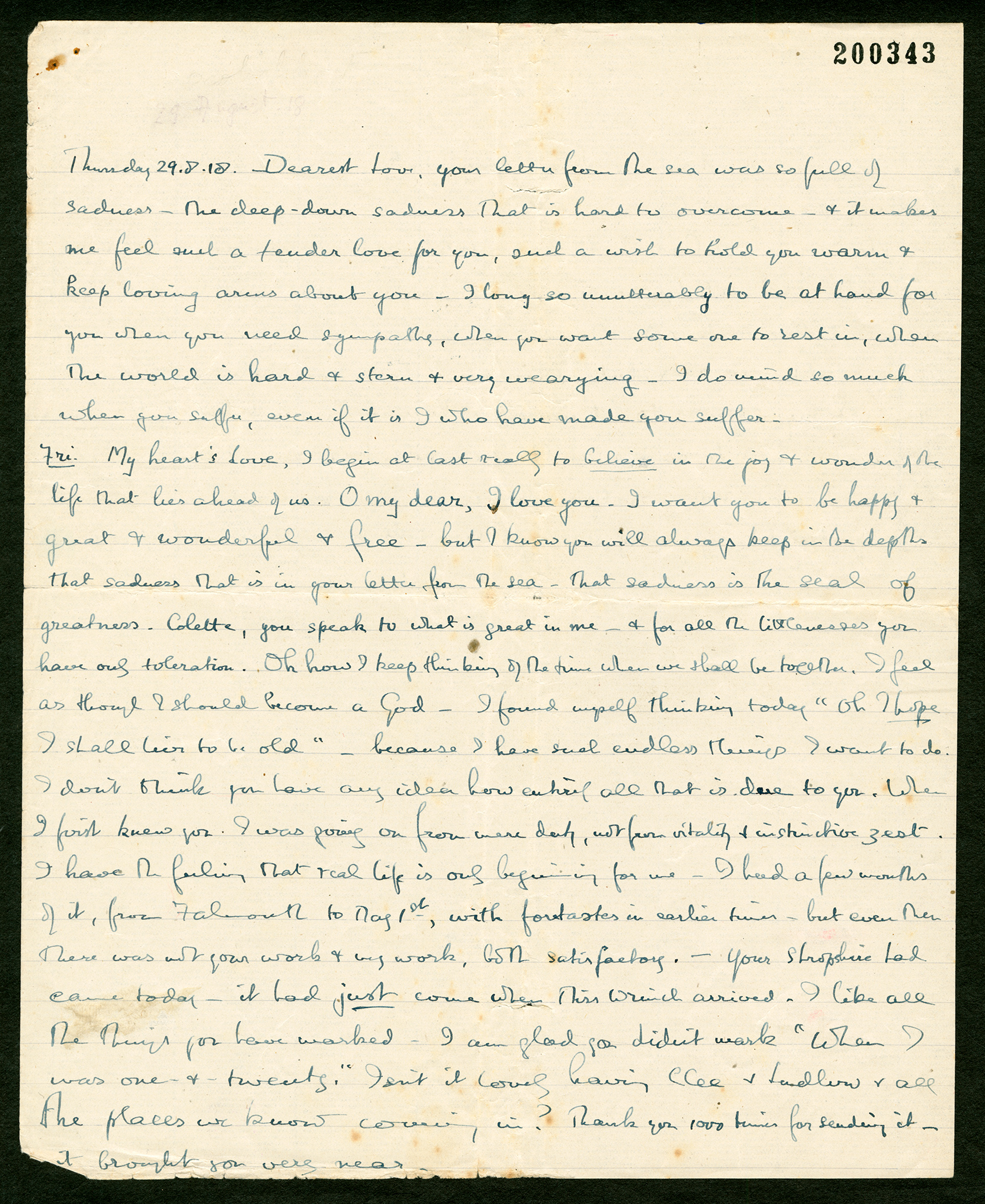

Thursday 29.8.18.

Dearest Love, your letter from the sea was so full of sadness2 — the deep-down sadness that is hard to overcome — and it makes me feel such a tender love for you, such a wish to hold you warm and keep loving arms about you. I long so unutterably to be at hand for you when you need sympathy, when you want some one to rest in, when the world is hard and stern and very wearying. I do mind so much when you suffer, even if it is I who have made you suffer.

Fri. My heart’s Love, I begin at last really to believe in the joy and wonder of the life that lies ahead of us. O my dear, I love you. I want you to be happy and great and wonderful and free — but I know you will always keep in the depths that sadness that is in your letter from the sea — that sadness is the seal of greatness. Colette, you speak to what is great in me — and for all the littlenesses you have only toleration. Oh how I keep thinking of the time when we shall be together. I feel as though I should become a God — I found myself thinking today “Oh I hope I shall live to be old” — because I have such endless things I want to do. I don’t think you have any idea how entirely all that is due to you. When I first knew you I was going on from mere duty, not from vitality and instinctive zest. I have the feeling that real life is only beginning for me. I had a few months of it, from Falmouth to May 1st,3 with foretastes in earlier times — but even then there was not your work and my work, both satisfactory. — Your Shropshire Lad4 came today — it had just come when Miss Wrinch arrived. I like all the things you have marked — I am glad you didn’t mark “When I was one-and-twenty.” Isn’t it lovely having Clee and Ludlow5 and all the places we know coming in?6 Thank you 1000 times for sending it — it brought you very near.

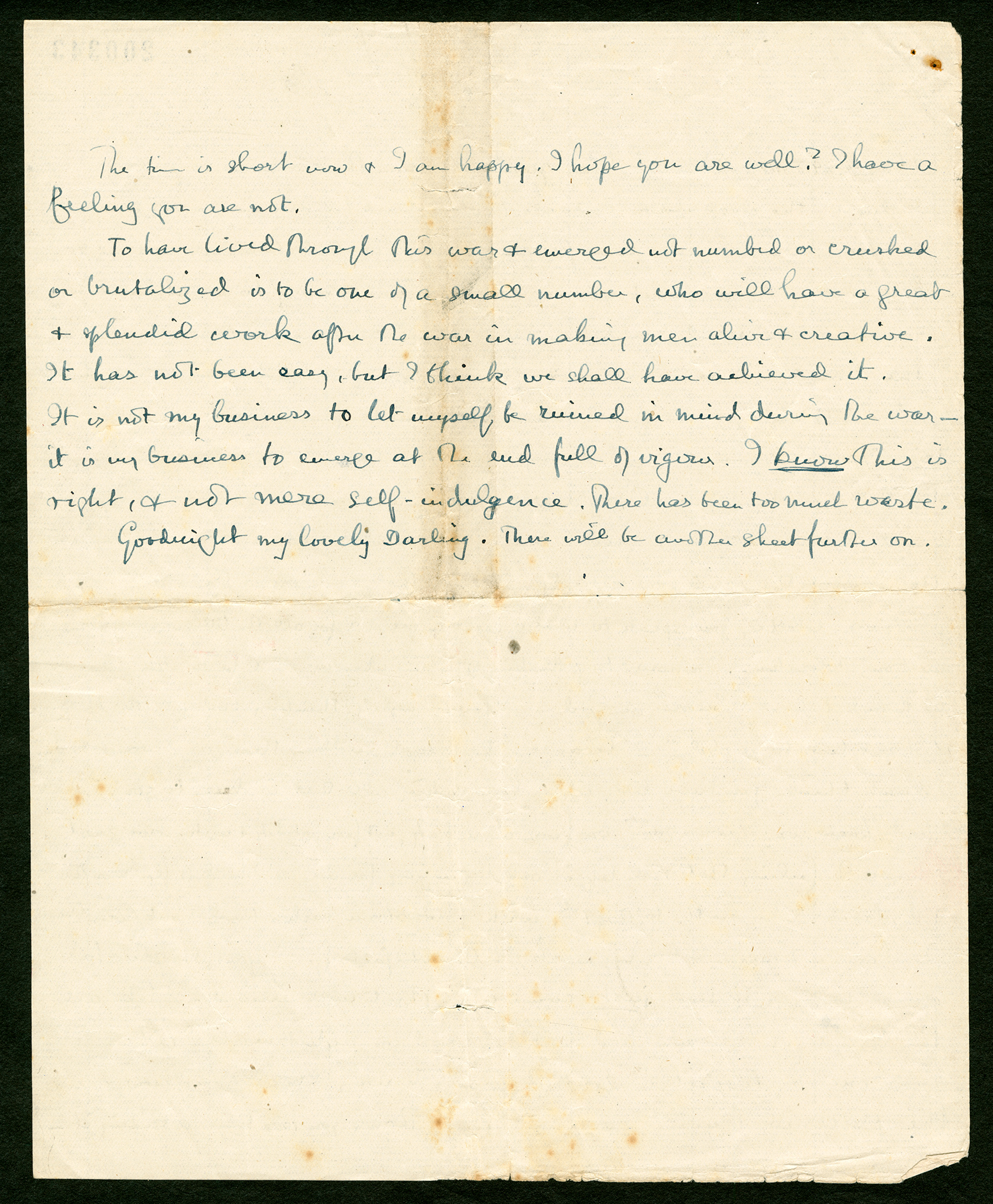

The time is short now and I am happy. I hope you are well? I have a feeling you are not.

To have lived through this war and emerged not numbed or crushed or brutalized is to be one of a small number, who will have a great and splendid work after the war in making men alive and creative. It has not been easy, but I think we shall have achieved it. It is not my business to let myself be ruined in mind during the war — it is my business to emerge at the end full of vigour. I know this is right, and not mere self-indulgence. There has been too much waste.

Goodnight my lovely Darling. There will be another sheet further on.7

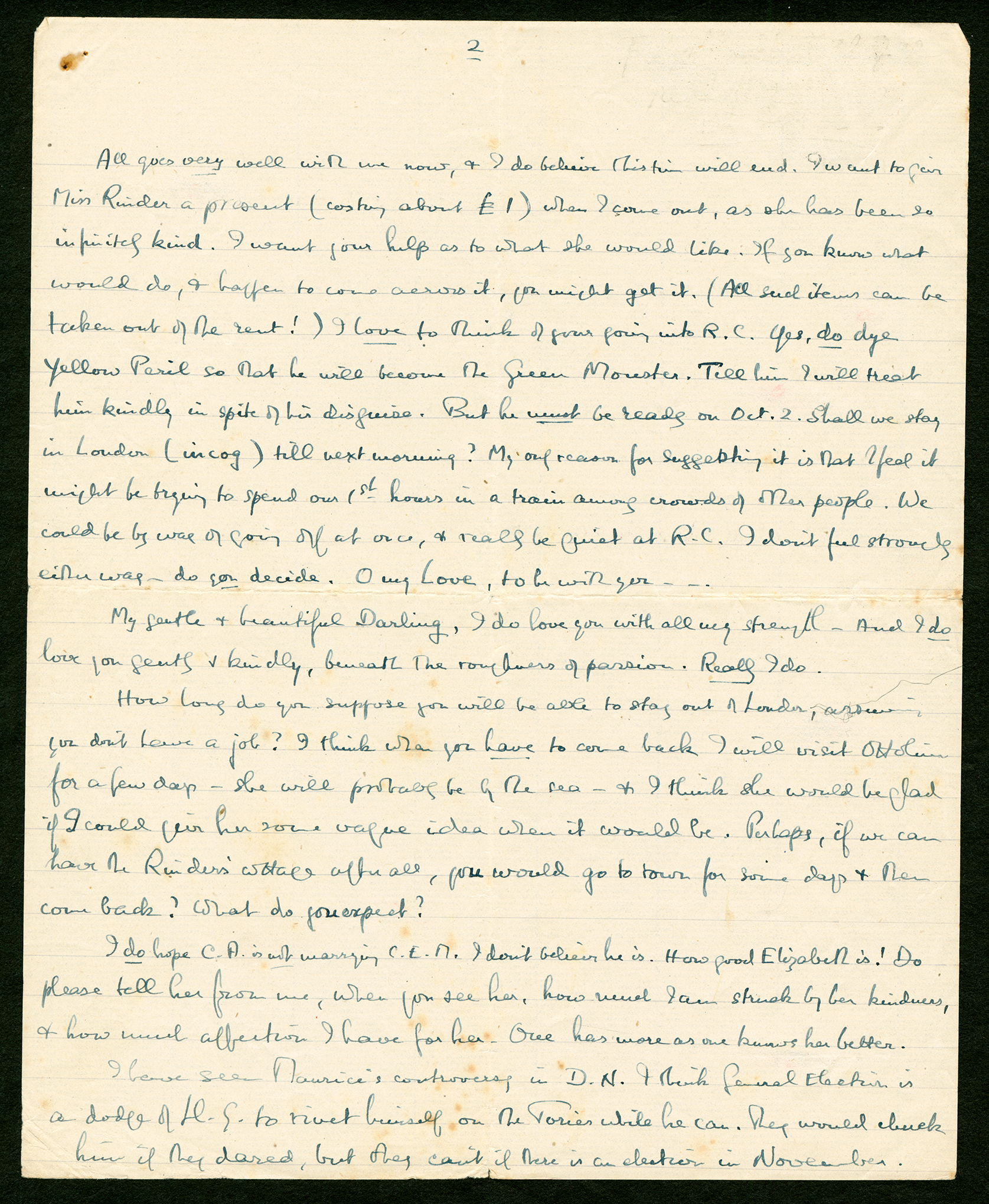

All goes very well with me now, and I do believe this time will end. I want to give Miss Rinder a present (costing about £1) when I come out, as she has been so infinitely kind. I want your help as to what she would like. If you know what would do, and happen to come across it, you might get it. (All such items can be taken out of the rent!) I love to think of your going into R.C. Yes, do dye Yellow Peril8 so that he will become the Green Monster. Tell him I will treat him kindly in spite of his disguise. But he must be ready on October 2.9 Shall we stay in London (incog) till next morning? My only reason for suggesting it is that I feel it might be trying to spend our 1st hours in a train among crowds of other people. We could be by way of going off at once, and really be quiet at R.C. I don’t feel strongly either way — do you decide. O my Love, to be with you — — .

My gentle and beautiful Darling, I do love you with all my strength. And I do love you gently and kindly, beneath the roughness of passion. Really I do.

How long do you suppose you will be able to stay out of London, assuming you don’t have a job? I think when you have to come back I will visit Ottoline for a few days — she will probably be by the sea — and I think she would be glad if I could give her some vague idea when it would be. Perhaps, if we can have the Rinders’ cottage10 after all, you would go to town for some days and then come back? What do you expect?

I do hope C.A. is not marrying C.E.M. I don’t believe he is. How good Elizabeth11 is! Do please tell her from me, when you see her, how much I am struck by her kindness, and how much affection I have for her. One has more as one knows her better.

I have seen Maurice’s controversy in D.N.12 I think the General Election is a dodge of Ll.G. to rivet himself on the Tories13 while he can. They would chuck him if they dared, but they can’t if there is an election in November.

Next Wed. I shall see you, and then only once more — 5 weeks today.14 It will be gone quickly. I am full of ideas for work, for all the years to come! I hope Exp. Theatre goes well.

Colette my Heart’s Love, I am so deeply happy through your love. I love you, I reverence your generous tenderness, the largeness of you. Goodnight my lovely Darling. I hope you have brought away something of the moonlit sea to keep the great music echoing in your heart. Imagine that I am stroking your hair and whispering gentle words of love. Goodnight, Beloved.

B.

Various matters of odd sorts in other parts of book.15

Is your health all right? Please let me know.

- 1

[document] This letter was edited from the initialled, two-sheet, twice-folded original in BR’s handwriting in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. Both sheets were folded so that the bottom half of the versos formed blank exteriors to add a measure of privacy to the contents.

- 2

Your letter from the sea was so full of sadness The letter that Colette wrote from St. Margaret’s Bay on 25 August 1918, at least in her edited version of it (the original having been lost), was sad only with reference to “past ache and pain”. It was just the opposite. She wrote: “I’ve treasured these few days rest from past ache and pain, and the longing and the waiting. I’m looking with hope and joy to the day we’ll go out into the world together, my Beloved” (BRACERS 113153). However, she may have edited the contents of the original.

- 3

from Falmouth to May 1st That is, from January 1918, when Colette returned from filming The Admirable Crichton in Falmouth, to the date of BR’s entry into Brixton.

- 4

Shropshire Lad A.E. Housman, The Shropshire Lad (1896), a book of poetry about the land and rural life of a locale favoured by Colette and BR. The book became quite popular. “When I Was One and Twenty” is a famous poem from the collection about the folly of giving your heart away. Housman (1859–1936) taught classics at Trinity College when BR lectured there. A 1913 letter from Housman to Alice Rothenstein (The Letters of A.E. Housman, ed. Archie Burnett [Oxford: Clarendon P., 2007]) records a brief conversation with BR. Housman considered BR’s departure from the College “a great loss”, but in 1919 he would not support his return because of BR’s “taking his name off the books of the College” (ibid., 1: 399).

- 5

Ludlow BR and Colette stayed at the Feathers Inn in Ludlow, Shropshire, on the second night of their idyllic August 1917 vacation before moving on to Ashford. See S. Turcon, “Then and Now: Bertie and Colette’s Escapes to the Peak District and Welsh Borderlands”, Russell 34 (2014): 117–30.

- 6

and all the places we know coming in? Other places (besides Clee and Ludlow) they knew that are mentioned in The Shropshire Lad are the River Teme and Knighton.

- 7

another sheet further on. In the book in which the present sheet had been concealed. The second sheet begins “All goes very well with me now”.

- 8

Yellow PerilColette’s dressing gown.

- 9

October 2 The date BR expected to be released early from Brixton.

- 10

Rinders’ cottageMiss Rinder offered her family’s cottage as a place to stay once BR left prison. Windmill Cottage was in Icklesham, near Winchelsea. Although not on the coast, it was not far away.

- 11

Elizabeth Elizabeth was going to let Wrinch occupy the Attic and Elizabeth would pay the rent.

- 12

Maurice’s controversy in D.N. The Liberal Daily News, which held the Prime Minister and the Coalition Government he led in rather low regard, had derided Maurice Elvey’s forthcoming opus, The Life Story of David Lloyd George (in which Colette had declined to act [Letter 59]), as a mere “General Election film” (“Under the Clock”, 26 Aug. 1918, p. 4). As quoted in the same unsigned column the next day, an evidently outraged Elvey insisted that there was “no political object” to this wholly artistic enterprise, which provided an “impartial” treatment of its subject’s life (p. 4). The Daily News, however, remained unconvinced by the director’s protestations. Ideal Film also reacted to suggestions that their project was a carefully timed piece of election propaganda, emphasizing that the screenplay had been written by a professional historian (Sir Sidney Low) and that the producers had received “not a penny in the way of subvention … from public or quasi-public funds” (“Mr. Lloyd George’s Life on the Film”, The Times, 27 Aug. 1918, p. 9). But the company would shortly receive a £20,000 payment (almost certainly from a government source) in exchange for the print and negatives, which resulted in the film being withheld from release. When it was rediscovered almost 80 years later, the film was in the possession of Lloyd George’s grandson Lord Tenby. Whether unfounded or not, suspicions that the production was a “political stunt” (Daily News, 30 Aug. 1918, p. 4) may have given the Prime Minister — already confident about his electoral prospects — cold feet about a venture he seems at one time to have favoured. He might instead have been seeking to distance himself from a lawsuit brought by Ideal Film against the popular jingoistic weekly, John Bull, which had published damaging insinuations about the national origins of the company’s founders, Harry and Simon Rowson, who were of Russian-Jewish descent (see Sarah Barrow and John White, eds., Fifty Key British Films [London and New York: Routledge, 2008], pp. 8–9). After careful restoration by the Welsh Film and Television Archive, The Life Story of David Lloyd George finally premiered in Cardiff in 1996 to belated critical acclaim.

- 13

General Election … dodge of Ll.G. to rivet … Tories As intimated by the preceding note, a general election was rumoured to be imminent in the late summer of 1918. Ultimately, however, Parliament was not dissolved until after the Armistice. But the qualms of the political opposition about a wartime election were hardly removed by holding one in its immediate aftermath, on 14 December 1918, when the Liberal Prime Minister and his Conservative allies (onto whom, effectively, Lloyd George had been “riveted” ever since his accession to the premiership) achieved a huge parliamentary majority.

- 14

Next Wed. I shall see you, and then only once more — 5 weeks today. I.e., 2 October, BR’s expected date of early release from Brixton. He was, in fact, let out earlier, on 14 September 1918.

- 15

other parts of book The book that contained smuggled letters.

Boismaison

Colette and BR vacationed at a house, The Avenue, owned by Mrs. Agnes Woodhouse and her husband, in the countryside near Ashford Carbonel, Shropshire, in August 1917. They nicknamed the house “Boismaison”. Agnes Woodhouse took in paying guests. Their first visit was idyllic. They returned for other vacations — in 1918 before he entered prison and in April 1919. Their plan to go soon after he got out of prison failed because their relationship faltered for a time. They discussed returning in the summer of 1919 — a booking was even made for 12–19 July — but in the end they didn’t go. See S. Turcon, “Then and Now: Bertie and Colette’s Escapes to the Peak District and Welsh Borderlands”, Russell 34 (2014): 117–30.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Catherine E. Marshall

Catherine E. Marshall (1880–1961), suffragist and internationalist who after August 1914 quickly moved from campaigning for women’s votes to protesting the war. An associate member of the No-Conscription Fellowship, she collaborated closely with BR during 1917 especially, when she was the organization’s Acting Hon. Secretary and he its Acting Chairman. Physically broken by a year of intense political work on behalf of the C.O. community, Marshall then spent several months convalescing with the NCF’s founding chairman, Clifford Allen, after he was released from prison on health grounds late in 1917. According to Jo Vellacott, Marshall was in love with Allen and “suffered deeply when he was imprisoned”. During his own imprisonment BR heard rumours that Marshall was to marry Allen (e.g., Letter 71), and Vellacott further suggests that the couple lived together during 1918 “in what seems to have been a trial marriage; Marshall was devastated when the relationship ended” (Oxford DNB). Throughout the inter-war period Marshall was active in the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

Clee Hill

Near Ashford Carbonel, Shropshire, where BR and Colette spent an idyllic summer holiday in August 1917, staying in house named “The Avenue”. BR mentioned the day at Clee Hill in several letters, the last on 8 September 1918 (Letter 100). What exactly happened on that day is not clear in any of his letters. However, in a prison message to BR, Colette remembered that a red fox came and listened to them there (Rinder to BR, 15 June 1918, BRACERS 79614). They also vacationed at The Avenue in March 1918, before BR entered prison.

Clifford Allen

(Reginald) Clifford Allen (1889–1939; Baron Allen of Hurtwood, 1932) was a socialist politician and publicist who joined the Cambridge University Fabian Society while studying at Peterhouse College (1908–11). After graduating he became active in the Independent Labour Party in London and helped establish a short-lived labour newspaper, the Daily Citizen. During the war Allen was an inspiring and effective leader of the C.O. movement as chairman of the No-Conscription Fellowship, which he co-founded with Fenner Brockway in November 1914. Court-martialled and imprisoned three times after his claim for absolute exemption from war service was rejected, Allen became desperately ill during his last spell of incarceration. He was finally released from the second division of Winchester Prison on health grounds in December 1917, but not before contracting the tuberculosis with which he was finally diagnosed in September 1918. He was dogged by ill health for the rest of his life. BR had enormous affection and admiration for Allen (e.g., 68 in Papers 13, 46 in Papers 14), a trusted wartime political associate. From February 1919 until March 1920 he even shared Allen’s Battersea apartment. A close friendship was soured, however, by Allen’s rejection of BR’s unforgiving critique of the Bolshevik regime, which both men witnessed at first hand with the British Labour Delegation to Russia in May 1920 (see Papers 15: 507). Yet Allen was far from revolutionary himself and did not even identify with the left wing of the ILP (which he chaired in the early 1920s). He was elevated to the peerage as a supporter of Ramsay MacDonald’s National Government, an administration despised by virtually the entire labour movement. Although Allen’s old intimacy with BR was never restored after the Russia trip, any lingering estrangement did not inhibit him from enrolling his daughter, Joan Colette (“Polly”) at the Russells’ Beacon Hill School.

David Lloyd George

Through ruthless political intrigue, David Lloyd George (1863–1945) emerged in December 1916 as the Liberal Prime Minister of a new and Conservative-dominated wartime Coalition Government. The “Welsh wizard” remained in that office for the first four years of the peace after a resounding triumph in the notorious “Coupon” general election of December 1918. BR despised the war leadership of Lloyd George as a betrayal of his Radical past as a “pro-Boer” critic of Britain’s South African War and as a champion of New Liberal social and fiscal reforms enacted before August 1914. BR was especially appalled by the Prime Minister’s stubborn insistence that the war be fought to a “knock-out” and by his punitive treatment of imprisoned C.O.s. For the latter policy, as BR angrily chastised Lloyd George at their only wartime meeting, “his name would go down to history with infamy” (Auto. 2: 24).

Dorothy Wrinch

Dorothy Maud Wrinch (1894–1976), mathematician, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. She studied mathematics and philosophy at Girton College, Cambridge, and came under BR’s influence in her second year when she took his course on mathematical logic. She taught mathematics at University College, London, 1918–21, and then at Oxford, 1922–30. Her first publications were in mathematical logic and philosophy, and during the 1920s she wrote on the philosophy of science. But in the 1930s her interests turned to mathematical biology and crystallography, and in 1935 she moved to the United States on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship and remained there for the rest of her life. Unfortunately, as a biologist she is best known for a long and stubborn controversy with Linus Pauling about the structure of proteins in which he was right and she was wrong. See Marjorie Senechal, I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science (New York: Oxford U. P., 2013). Chapter 7 is devoted to Wrinch’s interactions with BR in Brixton.

Elizabeth Russell

Elizabeth Russell, born Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941), was a novelist who in 1891 married Graf von Arnim-Schlagenthin. She became known as “Elizabeth”, the name she used in publishing Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898), and she remained widely known as Elizabeth von Arnim, although the Library of Congress catalogues her as Mary Annette (Beauchamp), Countess von Arnim. She was a widow when she married BR’s brother, Frank, on 11 February 1916. The marriage was quickly in difficulty; she left it for good in March 1919, but they were never divorced and she remained Countess Russell (becoming Dowager Countess after Frank’s death in 1931).

Experimental Theatre

Colette first mentioned that she and Miles were trying to start an Experimental Theatre in a letter of 24 June 1918 (BRACERS 113135), indicating that Miles would earn a tiny income from it. About a month later, she wrote that Elizabeth Russell had subscribed generously to the Theatre and that £700 had been raised, but hundreds still had to be found (BRACERS 113146). A few days later she wrote that Captain Stephen Gordon, a north-country lawyer working for the government, was to be the honorary treasurer, noting that he had “put most of the drive into the whole thing” (BRACERS 113147). During August Colette was happy with her involvement with the Theatre (Letter 68). John Galsworthy came to tea to discuss the project (c.14 Aug., BRACERS 113149). On 2 September she listed the members of the Theatre committee as “Desmond <MacCarthy>, Massingham, Galsworthy, and Dennis (Bradley)” (BRACERS 113155). The following day she wrote that she was learning three parts (BRACERS 113156). In her memoirs, Colette wrote about the “Experimental Little Theatre” but dated it 1919 (After Ten Years [London: Cape, 1931], pp. 129–30). An “artistic” theatre did get founded in 1920 in Hampstead, and John Galsworthy was connected to that venture, The Everyman Theatre — he was part of a reading committee which chose the works to be performed (The Times, 9 Sept. 1919, p. 8). The Everyman Theatre was under the direction of Norman MacDermott. In his book Everymania (London: Society for Theatre Research, 1975), he noted that he met Miles in the summer of 1918: they rented a store in Bloomsbury, had a cabinetmaker build sets, and put on plays with actors “bored with West-End theatres” (p. 10). It is likely that the Everyman Theatre was an out-growth of the Experimental Theatre.

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Maurice Elvey

Maurice Elvey (1887–1967) was a prolific film director (of silent pictures especially) and enjoyed a very successful career in that industry lasting many decades. Born William Seward Folkard into a working-class family, Elvey changed his name around 1910, when he was acting. He directed his first film, The Fallen Idol, in 1913. By 1917, when he directed Colette in Hindle Wakes, he had married for a second time — to a sculptor, Florence Hill Clarke — his first marriage having ended in divorce. Elvey and Colette had an affair during the filming of Hindle Wakes, beginning in September 1917, which caused BR great anguish. In addition to his feeling of jealousy during his imprisonment, BR was worried over the rumour that Elvey was carrying a dangerous sexually transmitted disease. (See BR, “My First Fifty Years”, RA1 210.007050–fos. 127b, 128, and Monk, 2: 507). Colette later maintained that Elvey cleared himself (“Letters to Bertrand Russell from Constance Malleson, 1916–1969”, p. 154, typescript, RA). BR removed the allegation from the Autobiography as published (see 2: 37), but he remained fearful. After Elvey’s long-lost wartime film about the life of Lloyd George was rediscovered and restored in the 1990s, it premiered to considerable acclaim (see Letter 87, note 12).

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

Russell Chambers

34 Russell Chambers, Bury Street (since renamed Bury Place), London WC1, BR’s flat since 1911. Helen Dudley rented the flat in late 1916 or early 1917. In May 1918 she sublet it to Clare Annesley. Colette moved in on 9 September 1918 and stayed until June 1919. BR did not give up the lease until December 1923. See S. Turcon, “Russell Chambers, Other London Flats, and Country Homes, 1911–1923”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 150 (Fall 2014): 30–4. “Russell Chambers, Other London Flats, and Country Homes, 1911–1923”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 150 (Fall 2014): 30–4.

The Attic

The Attic was the nickname of the flat at 6 Mecklenburgh Square, London WC1, rented by Colette and her husband, Miles Malleson. The house which contained this flat is no longer standing. “The spacious and elegant facades of Mecklenburgh Square began to be demolished in 1950. The houses on the north side were banged into dust in 1958. The New Attic was entirely demolished” (“Letters to Bertrand Russell from Constance Malleson, 1916–1969”, p. 109; typescript in RA).

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.