Brixton Letter 81

BR to Constance Malleson

August 24, 1918

- AL

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-81

BRACERS 19350

<Brixton Prison>1

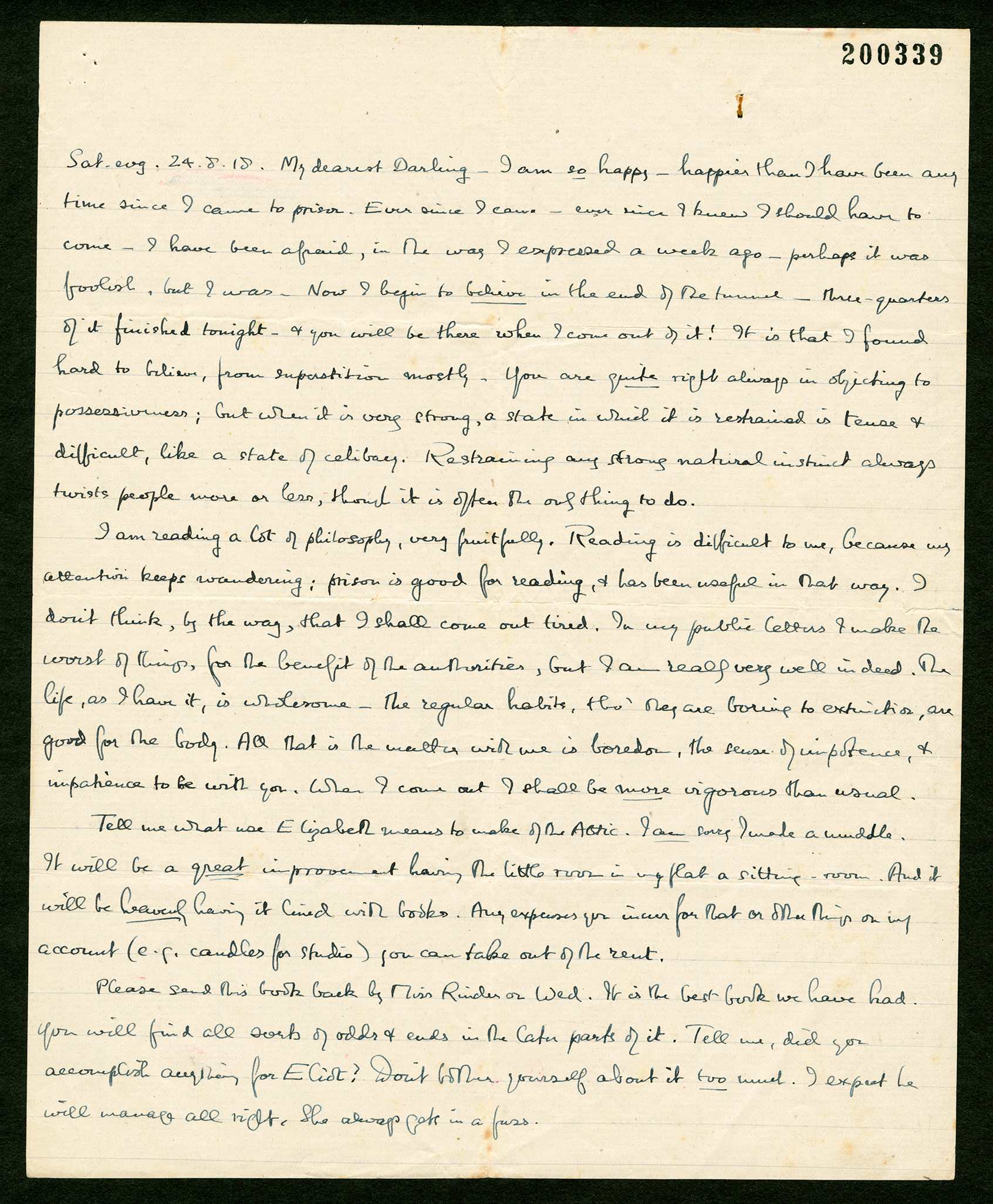

Sat. evg. 24.8.18.

My dearest Darling

I am so happy — happier than I have been any time since I came to prison. Ever since I came — ever since I knew I should have to come — I have been afraid, in the way I expressed a week ago — perhaps it was foolish, but I was. Now I begin to believe in the end of the tunnel — three-quarters of it finished tonight2 — and you will be there when I come out of it! It is that I found hard to believe, from superstition mostly. You are quite right always in objecting to possessiveness;3 but when it is very strong, a state in which it is restrained is tense and difficult, like a state of celibacy. Restraining any strong natural instinct always twists people more or less, though it is often the only thing to do.

I am reading a lot of philosophy, very fruitfully. Reading is difficult to me, because my attention keeps wandering; prison is good for reading, and has been useful in that way. I don’t think, by the way, that I shall come out tired. In my public letters4 I make the worst of things, for the benefit of the authorities, but I am really very well indeed. The life, as I have it, is wholesome — the regular habits, tho’ they are boring to extinction, are good for the body. All that is the matter with me is boredom, the sense of impotence, and impatience to be with you. When I come out I shall be more vigorous than usual.

Tell me what use Elizabeth means to make of the Attic.5 I am sorry I made a muddle.6 It will be a great improvement having the little room in my flat a sitting-room. And it will be heavenly having it lined with books. Any expenses you incur for that or other things on my account (e.g. candles for Studio) you can take out of the rent.

Please send this book back by Miss Rinder on Wed. It is the best book we have had.7 You will find all sorts of odds and ends in the later parts of it. Tell me, did you accomplish anything for Eliot?8 Don’t bother yourself about it too much. I expect he will manage all right, she9 always gets in a fuss.

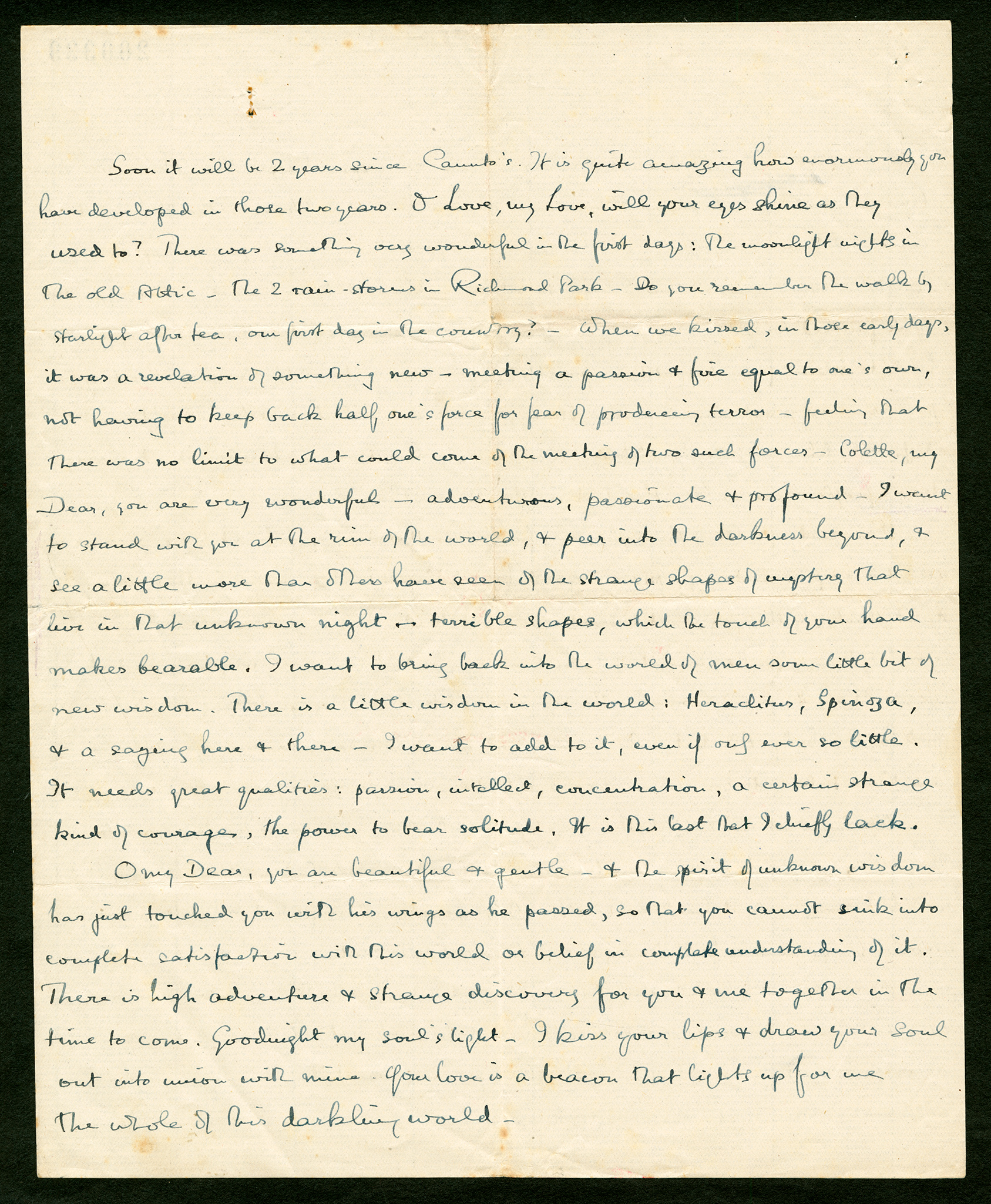

Soon it will be 2 years since Canuto’s.10 It is quite amazing how enormously you have developed in those two years. O Love, my Love, will your eyes shine as they used to? There was something very wonderful in the first days: the moonlight nights in the old Attic11 — the 2 rain-storms in Richmond Park.12 Do you remember the walk by starlight after tea, our first day in the country?13— When we kissed, in those early days, it was a revelation of something new — meeting a passion and fire equal to one’s own, not having to keep back one’s force for fear of producing terror — feeling that there was no limit to what could come of the meeting of two such forces. Colette, my Dear, you are very wonderful — adventurous, passionate and profound. I want to stand with you at the rim of the world,14 and peer into the darkness beyond, and see a little more than others have seen of the strange shapes of mystery that live in that unknown night — terrible shapes, which the touch of your hand makes bearable. I want to bring back into the world of men some little bit of new wisdom. There is a little wisdom in the world: Heraclitus,15 Spinoza,16 and a saying here and there. I want to add to it, even if only ever so little. It needs great qualities: passion, intellect, concentration, a certain strange kind of courage, the power to bear solitude. It is this last that I chiefly lack.

O my Dear, you are beautiful and gentle — and the spirit of unknown wisdom has just touched you with his wings as he passed, so that you cannot sink into complete satisfaction with this world or belief in complete understanding of it. There is high adventure and strange discovery for you and me together in the time to come. Goodnight my soul’s light. I kiss your lips and draw your soul out into union with mine. Your love is a beacon that lights up for me the whole of this darkling world.a

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the unsigned, thrice-folded original in BR’s hand in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives.

- 2

three-quarters of it finished tonight On the basis of this calculation, BR clearly projected an early release date of the beginning of October. For several weeks he had been mentioning 2 October as the date.

- 3

possessiveness BR had difficulty restraining his possessiveness. On 16 October 1917 (BRACERS 19231) he wrote about it in his letter and enclosed a separate manuscript (document 200218), “Possessiveness in Sex-Relations”. He returned to this theme in his letter of 16 January 1918 (BRACERS 19277), writing: “All will come right if … the grasping possessiveness in me is kept under.”

- 4

my public letters BR was still, apparently, writing a weekly letter (or “manifesto”, Letter 79). Parts of it were extracted and circulated to his friends.

- 5

Elizabeth means to make of the Attic Although BR’s sister-in-law, Elizabeth, rented the Attic (thus allowing Colette to move into BR’s Bury Street flat), she did not live there — instead she sublet it to Dorothy Wrinch.

- 6

I made a muddle Details of the “muddle” were presumably in the same letter in which Colette told him of her plans for the sitting-room. The letter does not seem to be extant.

- 7

best book we have had To conceal documents smuggled into and out of the prison.

- 8

accomplish anything for EliotColette did introduce T.S. Eliot to an American colonel she had met through her mother. Many years later Eliot recollected that this army officer, J. Mitchell, “was very suspicious of the introduction, and wanted to be quite sure that I was not ‘a socialist like Lady Malleson’” (Eliot to Colette, 5 Sept. 1961, BRACERS 131600). It is not clear what, if anything, resulted from their meeting at Russell Chambers on 11 September 1918, for, in the end, Eliot served very briefly in the US navy after being called up in the final weeks of the war.

- 9

she Presumably Eliot’s wife, Vivienne (1888–1947).

- 10

Canuto’s They dined together at Canuto’s restaurant on Baker Street and then went to Colette’s flat in Bernard Street, where their love affair began in the early morning hours of 24 September 1916.

- 11

the old Attic The flat at 43 Bernard Street that Colette was living in when they met.

- 12

2 rain-storms in Richmond Park They had spent a memorable day in Richmond Park early in their relationship, on 24 October 1916, Colette’s birthday (see BRACERS 112952). The following month, in Letter 100, BR again recollected their time in Richmond Park.

- 13

our first day in the country? Their first country walk took place on 1 October 1916 from Goring, Oxfordshire.

- 14

I want to stand with you at the rim of the world BR wrote similarly to Colette in Letter 103 and on 8 June 1919 (“I want to stand with you on the rim of the world”, BRACERS 19487).

- 15

Heraclitus On 20 February 1914, BR told Lucy Donnelly that “of all men that ever lived, Heraclitus is the most intimate to me” (SLBR 1: 495). In this BR was implicitly contrasting him with Plato, a philosopher with whom BR’s early work is often associated. “Yes,” he had told Ottoline a year earlier, “Plato is wonderful. But he is not intimate to me — I haven’t enough urbanity for him” (16 Sept. 1913; SLBR 1: 477). In addition to his lack of urbanity, BR’s adoption of an event ontology as part of his neutral monism in 1918 gave him a new reason to admire Heraclitus, for Heraclitus’s most famous metaphysical doctrine is that everything is in flux. BR even wrote out Heraclitus’s extant fragments for a friend (Helen Dudley’s sister, Katharine) (RA Rec. Acq. 27). Virtually nothing is known of the life of the pre-Socratic philosopher, but the fragments of his work reveal a love of strife, a hatred of democracy, and a contempt for mankind, traits which led BR later to revise his opinion (see the chapter on Heraclitus in HWP, p. 41). In 1937, writing again to Ottoline, BR put Heraclitus at the beginning of a long tradition which ended with Hitler (15 Feb., 1937; SLBR 2: 344). It seems that BR’s earlier admiration of Heraclitus was based on the latter’s scepticism and angry iconoclasm, and possibly his ethic of “proud asceticism” (HWP, p. 42). BR’s early knowledge of Heraclitus came from John Burnet’s Early Greek Philosophy (2nd ed. [London: A. and C. Black, 1908]; Russell’s library).

- 16

Spinoza Benedictus de Spinoza (1632–1677), rationalist philosopher. BR described Spinoza as “the noblest and most lovable of the great philosophers. Intellectually, some others have surpassed him, but ethically he is supreme” (HWP, p. 569). The persistence of BR’s admiration of Spinoza is shown by the fact that at the age of 92 BR declared: “Spinoza has been a great influence in my life and an influence of a practical sort” (transcript of filmed interview, pp. 12–13; cited in K. Blackwell, The Spinozistic Ethics of Bertrand Russell [London: Allen & Unwin, 1985], pp. 21–2).

Textual Notes

- a

… this darkling world. The handwriting of this letter is so even and invariable, and without insertions and deletions, that it could well be a fair copy from a draft.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Dorothy Wrinch

Dorothy Maud Wrinch (1894–1976), mathematician, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. She studied mathematics and philosophy at Girton College, Cambridge, and came under BR’s influence in her second year when she took his course on mathematical logic. She taught mathematics at University College, London, 1918–21, and then at Oxford, 1922–30. Her first publications were in mathematical logic and philosophy, and during the 1920s she wrote on the philosophy of science. But in the 1930s her interests turned to mathematical biology and crystallography, and in 1935 she moved to the United States on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship and remained there for the rest of her life. Unfortunately, as a biologist she is best known for a long and stubborn controversy with Linus Pauling about the structure of proteins in which he was right and she was wrong. See Marjorie Senechal, I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science (New York: Oxford U. P., 2013). Chapter 7 is devoted to Wrinch’s interactions with BR in Brixton.

Elizabeth Russell

Elizabeth Russell, born Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941), was a novelist who in 1891 married Graf von Arnim-Schlagenthin. She became known as “Elizabeth”, the name she used in publishing Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898), and she remained widely known as Elizabeth von Arnim, although the Library of Congress catalogues her as Mary Annette (Beauchamp), Countess von Arnim. She was a widow when she married BR’s brother, Frank, on 11 February 1916. The marriage was quickly in difficulty; she left it for good in March 1919, but they were never divorced and she remained Countess Russell (becoming Dowager Countess after Frank’s death in 1931).

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

Russell Chambers

34 Russell Chambers, Bury Street (since renamed Bury Place), London WC1, BR’s flat since 1911. Helen Dudley rented the flat in late 1916 or early 1917. In May 1918 she sublet it to Clare Annesley. Colette moved in on 9 September 1918 and stayed until June 1919. BR did not give up the lease until December 1923. See S. Turcon, “Russell Chambers, Other London Flats, and Country Homes, 1911–1923”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 150 (Fall 2014): 30–4. “Russell Chambers, Other London Flats, and Country Homes, 1911–1923”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 150 (Fall 2014): 30–4.

T.S. Eliot

The poet and critic Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888–1965) was a student of BR’s at Harvard in 1914. BR had sensed his ability, especially “a certain exquisiteness of appreciation” (to Lucy Donnelly, 11 May 1914; SLBR 1: 491), but did not see a genius in embryo. After Eliot travelled to England later the same year, to study philosophy at Oxford under H.H. Joachim, BR became something of a father figure to the younger man. He also befriended Eliot’s (English) wife, Vivienne, whom he had hastily married in 1915 and with whom BR may have had an affair the following year. BR shared his Bloomsbury apartment (at 34 Russell Chambers) with the couple for more than a year after their marriage, and jointly rented a property with them in Marlow, Bucks. (see Letter 78). He further eased Eliot’s monetary concerns by arranging paid reviewing for him and giving him £3,000 in debentures from which BR was reluctant, on pacifist grounds, to collect the income (Auto. 2: 19). Eliot’s financial security was much improved by obtaining a position at Lloyd’s Bank in 1917, but during BR’s imprisonment he faced uncertainty of a different kind as the shadow of conscription loomed over him (see, e.g., Letter 27). Nine years after the war ended Eliot returned the securities (BRACERS 76480).

The Attic

The Attic was the nickname of the flat at 6 Mecklenburgh Square, London WC1, rented by Colette and her husband, Miles Malleson. The house which contained this flat is no longer standing. “The spacious and elegant facades of Mecklenburgh Square began to be demolished in 1950. The houses on the north side were banged into dust in 1958. The New Attic was entirely demolished” (“Letters to Bertrand Russell from Constance Malleson, 1916–1969”, p. 109; typescript in RA).

The Studio

The accommodation BR and Colette rented on the ground floor at 5 Fitzroy Street, just off Howland Street, London W1. “It had a top light, a gas fire and ring. A water tap and lavatory in the outside passage were shared with a cobbler whose workshop adjoined” (Colette’s annotation at BRACERS 113087). It was ready to occupy in November 1917.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.