Brixton Letter 72

BR to Constance Malleson

August 16, 1918

- AL/TL(TC)

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-72

BRACERS 19346

<Brixton Prison>1

Friday2

Oh if I could only have one hour with you in freedom. I want you so. I am losing the courage that is needed for hope. I can’t believe we shall be happy — and then it all grows black and I want to force on swift irremediable disaster, so as to have done with the agony of fearing that it will come. I started to read “Madge”3, a but in two minutes it broke me down and I had to stop. I have to avoid everything soft when I am in this mood. — The first months I still felt your arms round me and it comforted me — now I feel them round other people and it comforts me less! It is not really anything you have done that has made the difference — only that solitude and confinement tell on one.

You ask if your sympathy for people is genuine — nine tenths of it isn’t, the other tenth is genuine, and with luck will develope. You have never yet known unhappiness (though you may think you have), so you haven’t yet as much heart as you will have when you know better what people are enduring. But you have a certain amount of heart, whereas most people have none at all.

Dear one, stretch out your arms to me — I am in a great darkness and I want the touch of loving hands.b

You will find enclosed a discussion of “The International Situation”4 — partly in answer to your remarks.5 When you have read it, please give it to Miss Rinder. I want copies to Garsington,6 and to Massingham (not for publication). It may be shown to any one sympathetic. Could be published as Edward Grubb’s!7 But not as mine.

- 1

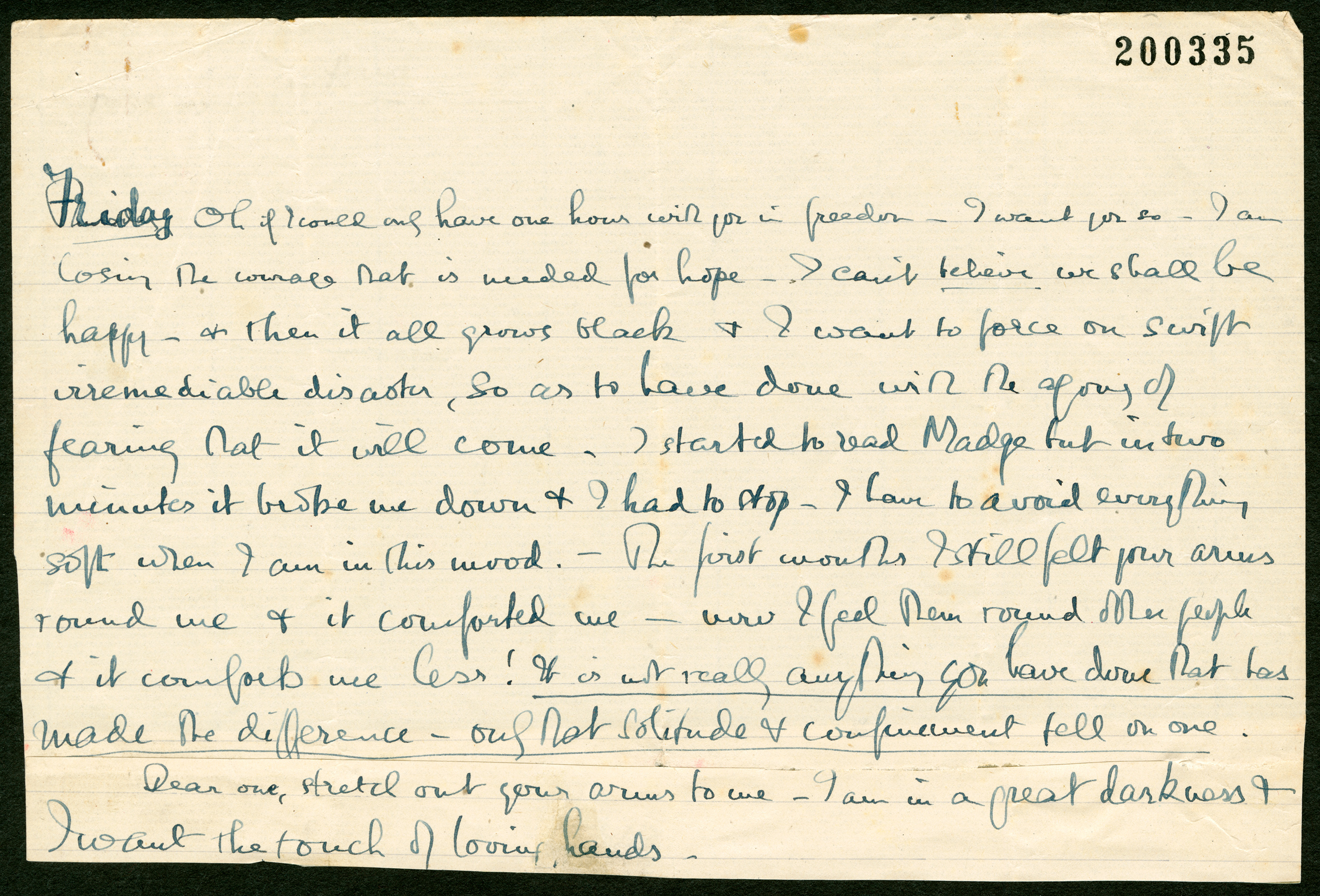

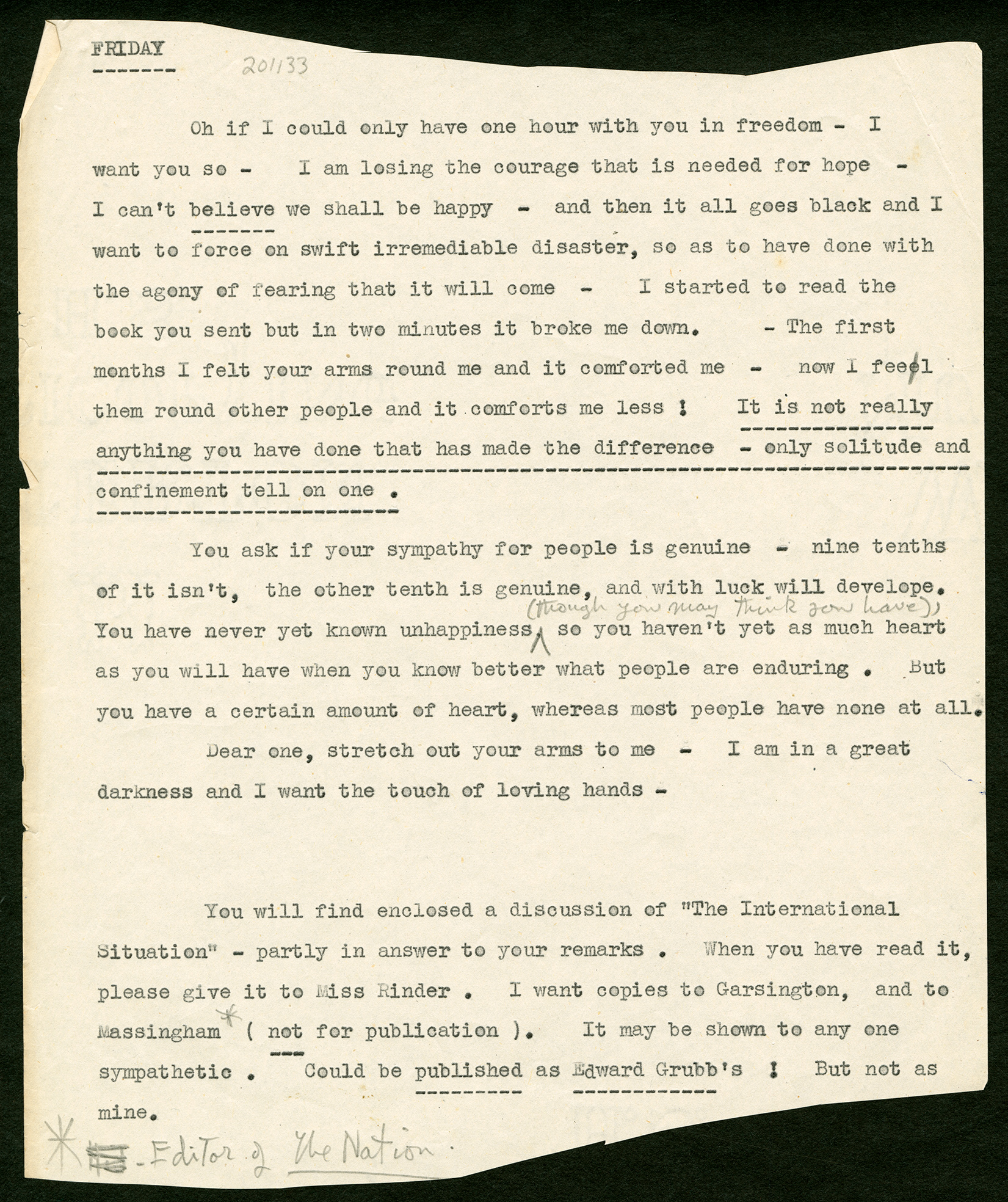

[document] The letter was edited from two documents, one manuscript and one typed, in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. The unsigned manuscript in BR’s handwriting (BRACERS 19346) has two parts. The first part concludes with the end of the first paragraph. The second is a single sentence beginning “Dear one” and ending with “hands”. This sentence has been cut from somewhere (presumably the foot of the letter containing this text) and stuck to it with tape. The second part of this letter, BRACERS 116369, is typed. The typed transcription was made by Colette at a later date. It begins with paragraph two “You ask if …” and ends with the end of the letter. The sentence that the two documents share is the one beginning “Dear one”. The placement of this sentence is in accordance with its placement in document 201133. Document 201133 retains BR’s spelling “develope”.

- 2

[date] “Friday” is written over “Thursday”. There is a typed and handwritten note, “This may be Friday 16th August 1918”, inserted by Colette or her editor.

- 3

to read “Madge”Colette had sent BR the “script of ‘Madge’” (which was by Miles Malleson). The part of Madge was one of three she had to prepare for the Experimental Theatre (BRACERS 113156 and 113155).

- 4

“The International Situation” The title of the manuscript was “The International Outlook” (RA Rec. Acq. 500). A penetrating analysis of current affairs, it did not appear in The Tribunal under Grubb’s name or anyone else’s, and indeed remained unpublished until it was included as Paper 100 in Papers 14.

- 5

partly in answer to your remarks Her remarks on international affairs cannot be found. She may have made them to BR during a recent visit to Brixton, in a lost letter, or one from which the remarks were removed in her editing of it.

- 6

Garsington By extension, the intellectuals and politicians who frequented it. Ottoline responded herself to “The International Outlook”: “We read your Précis of Foreign Affairs that you sent to Miss Rinder. It is extraordinly <sic> good. Terribly so. It seems such a pity it can’t be published” (25 Aug. 1918, BRACERS 114756).

- 7

Edward Grubb Grubb (1854–1939) was a Quaker, greatly admired by BR and others in the No-Conscription Fellowship for his goodness and common sense. He owned and edited the British Friend, 1901–13, was a highly effective fundraiser as honorary treasurer of the NCF, 1915–19, and active in the Fellowship of Reconciliation (a religious pacifist organization founded in December 1914). BR wrote of him: “He was, when I first knew him, a man of seventy, very quiet, very adverse from publicity, and very immovable.… He acted on behalf of the young men in prison with a complete absence of even the faintest trace of self-seeking” (Auto. 2: 39–40).

Textual Notes

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.

Experimental Theatre

Colette first mentioned that she and Miles were trying to start an Experimental Theatre in a letter of 24 June 1918 (BRACERS 113135), indicating that Miles would earn a tiny income from it. About a month later, she wrote that Elizabeth Russell had subscribed generously to the Theatre and that £700 had been raised, but hundreds still had to be found (BRACERS 113146). A few days later she wrote that Captain Stephen Gordon, a north-country lawyer working for the government, was to be the honorary treasurer, noting that he had “put most of the drive into the whole thing” (BRACERS 113147). During August Colette was happy with her involvement with the Theatre (Letter 68). John Galsworthy came to tea to discuss the project (c.14 Aug., BRACERS 113149). On 2 September she listed the members of the Theatre committee as “Desmond <MacCarthy>, Massingham, Galsworthy, and Dennis (Bradley)” (BRACERS 113155). The following day she wrote that she was learning three parts (BRACERS 113156). In her memoirs, Colette wrote about the “Experimental Little Theatre” but dated it 1919 (After Ten Years [London: Cape, 1931], pp. 129–30). An “artistic” theatre did get founded in 1920 in Hampstead, and John Galsworthy was connected to that venture, The Everyman Theatre — he was part of a reading committee which chose the works to be performed (The Times, 9 Sept. 1919, p. 8). The Everyman Theatre was under the direction of Norman MacDermott. In his book Everymania (London: Society for Theatre Research, 1975), he noted that he met Miles in the summer of 1918: they rented a store in Bloomsbury, had a cabinetmaker build sets, and put on plays with actors “bored with West-End theatres” (p. 10). It is likely that the Everyman Theatre was an out-growth of the Experimental Theatre.

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

H.W. Massingham

H.W. Massingham (1860–1924), radical journalist and founding editor in 1907 of The Nation, a publication which superseded The Speaker and soon became Britain’s foremost Liberal weekly. Almost immediately the editor of the new periodical started to host a weekly luncheon (usually at the National Liberal Club), which became a vital forum for the exchange of “New Liberal” ideas and strategies between like-minded politicians, publicists and intellectuals (see Alfred F. Havighurst, Radical Journalist: H.W. Massingham, 1860–1924 [Cambridge: U. P., 1974], pp. 152–3). On 4 August 1914, BR attended a particularly significant Nation lunch, at which Massingham appeared still to be in favour of British neutrality (see Papers 13: 6) — which had actually ended at the stroke of midnight. By the next day, however, Massingham (like many Radical critics of Britain’s pre-war diplomacy) had come to accept the case for military intervention, a position he maintained (not without misgivings) for the next two years. Massingham was still at the helm of the Nation when it merged with the more literary-minded Athenaeum in 1921; he finally relinquished editorial control two years later. In 1918 he served on Miles and Constance Malleson’s Experimental Theatre Committee.

Miles Malleson

Miles Malleson (1888–1969), actor and playwright, was born in Croydon, Surrey, the son of Edmund and Myrrha Malleson. He married his first wife, a fellow actor, Lady Constance Annesley (stage name, Colette O’Niel), in 1915. They had met at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts). Their marriage was an “open” one. In 1914 Miles enlisted in the City of London Fusiliers and was sent to Malta. He became ill and was discharged, unfit for further service. He became active in the No-Conscription Fellowship and wrote anti-war stage plays as well as a pamphlet, Cranks and Commonsense (1916). In the 1930s he began to write for the screen and act in films, in which he became a very well-known character actor, as well as continuing his stage career at the Old Vic in London. He married three times: his second marriage was to Joan Billson, a physician (married 1923, divorced 1940), with whom he had two children; his third wife was Tatiana Lieven, an actress (married 1946). He died in London in March 1969.

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.