Brixton Letter 71

BR to Constance Malleson

August 15, 1918

- AL

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila TurconCite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, russell-letters.mcmaster.ca

/brixton-letter-71Auto. 2: 88; SLBR 2: #320

BRACERS 19345

<Brixton Prison>1

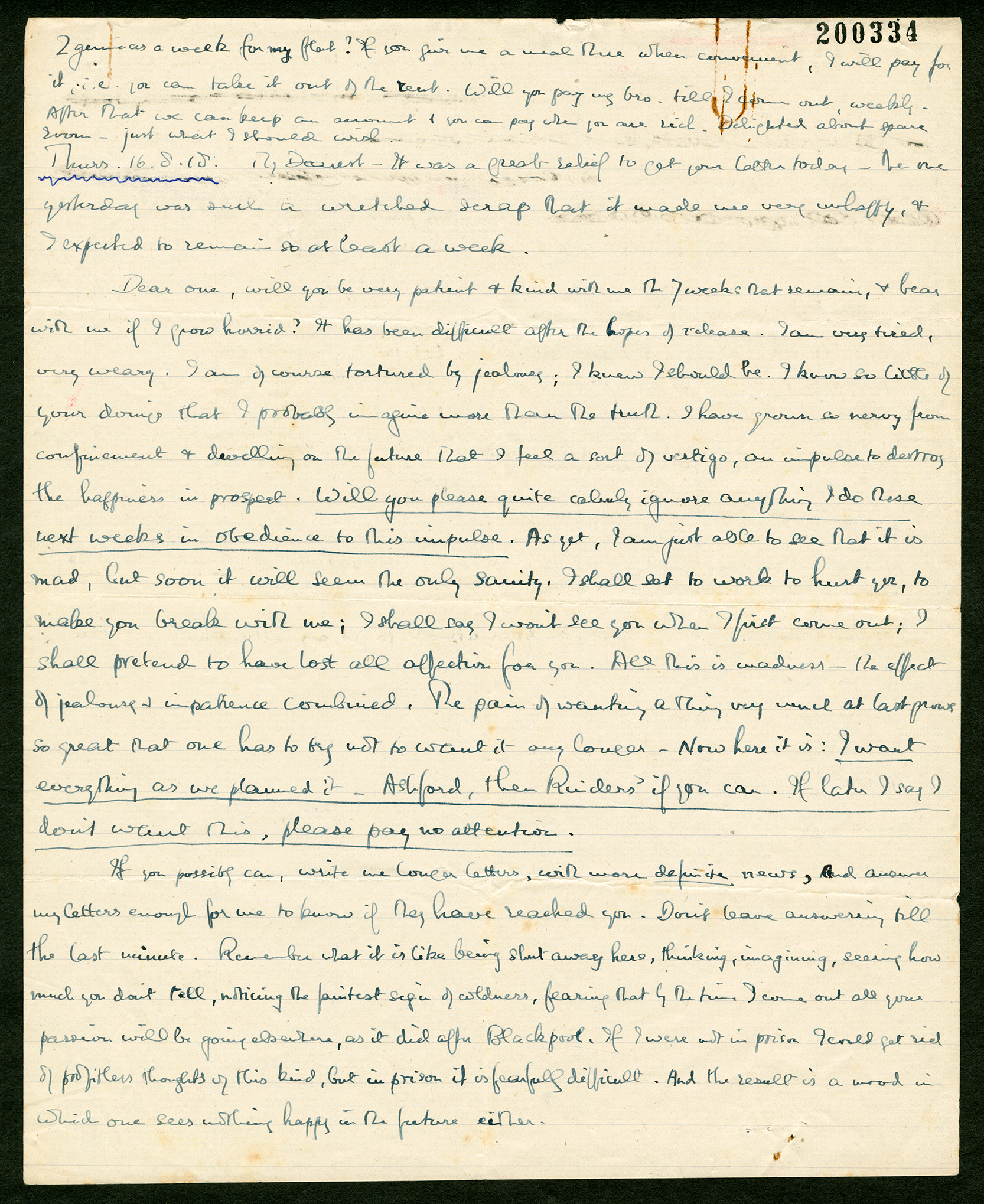

Thurs. 16.8.18.2

My Dearest

It was a great relief to get your letter today — the one yesterday was such a wretched scrap3 that it made me very unhappy, and I expected to remain so at least a week.

Dear one, will you be very patient and kind with me the 7 weeks that remain,4 and bear with me if I grow horrid? It has been difficult after the hopes of release. I am very tired, very weary. I am of course tortured by jealousy;5 I knew I should be. I know so little of your doings that I probably imagine more than the truth. I have grown so nervy from confinement and dwelling on the future that I feel a sort of vertigo, an impulse to destroy the happiness in prospect. Will you please quite calmly ignore anything I do these next weeks in obedience to this impulse. As yet, I am just able to see that it is mad, but soon it will seem the only sanity. I shall set to work to hurt you, to make you break with me; I shall say I won’t see you when I first come out; I shall pretend to have lost all affection for you. All this is madness — the effect of jealousy and impatience combined. The pain of wanting a thing very much at last grows so great that one has to try not to want it any longer. Now here it is: I want everything as we planned it — Ashford, then Rinders’6 if you can. If later I say I don’t want this, please pay no attention.

If you possibly can, write me longer letters, with more definite news, and answer my letters enough for me to know if they have reached you. Don’t leave answering till the last minute. Remember what it is like being shut away here, thinking, imagining, seeing how much you don’t tell, noticing the faintest sign of coldness, fearing that by the time I come out all your passion will be going elsewhere, as it did after Blackpool.7 If I were not in prison I could get rid of profitless thoughts of this kind, but in prison it is fearfully difficult. And the result is a mood in which one sees nothing happy in the future either.

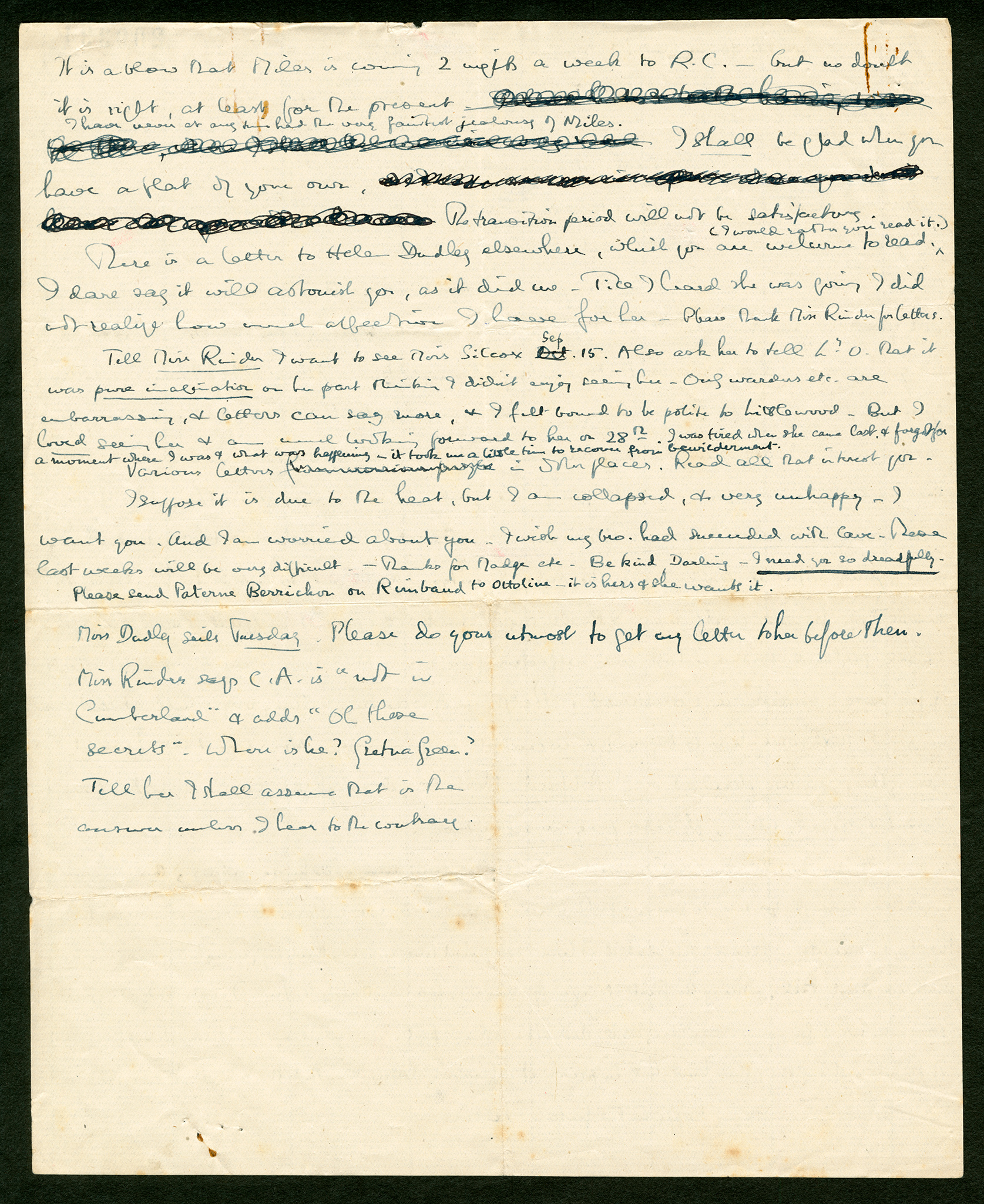

It is a blow that Miles is coming 2 nights a week to R.C.8 — but no doubt it is right, at least for the present.a I have never at any time had the very faintest jealousy of Miles.b I shall be glad when you have a flat of your own.c The transition period will not be satisfactory.

There is a letter to Helen Dudley9 elsewhere, which you are welcome to read. (I would rather you read it.)d I dare say it will astonish you, as it did me. Till I heard she was going I did not realize how much affection I have for her. Please thank Miss Rinder for letters.10

Tell Miss Rinder I want to see Miss Silcox Sep.e 15. Also ask her to tell Ly. O. that it was pure imagination on her part thinking I didn’t enjoy seeing her.11 Only warders etc. are embarrassing, and letters can say more, and I felt bound to be polite to Littlewood. But I loved seeing her and much looking forward to her on 28th. I was tired when she came last, and forgot for a moment where I was and what was happening — it took me a little time to recover from bewilderment.f

Various lettersg in other places.12 Read all that interest you.

I suppose it is due to the heat, but I am collapsed and very unhappy. I want you. And I am worried about you. I wish my brother had succeeded with Cave.13 These last weeks will be very difficult. — Thanks for “Madge”14, h etc. Be kind Darling — I need you so dreadfully.

Please send Paterne Berrichon on Rimbaud15 to Ottoline — it is hers and she wants it.

Miss Dudley sails Tuesday. Please do your utmost to get my letter to her before then.

Miss Rinder says C.A. is “not in Cumberland” and adds “Oh these secrets”. Where is he? Gretna Green?16 Tell her I shall assume that is the answer unless I hear to the contrary.

2 guineas a week17, i for my flat? If you give me a meal there when convenient, I will pay for it, i.e. you can take it out of the rent. Will you pay my brother till I come out, weekly. After that we can keep an account and you can pay when you are rich. Delighted about spare room18 — just what I should wish.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the unsigned, thrice-folded sheet in BR’s hand in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. The folding was done so that the resulting exterior surfaces were blank. The letter was extracted in BR’s Autobiography, 2: 88, and published as #320 in Vol. 2 of his Selected Letters.

- 2

[date] 16 August was a Friday; thus, on the basis that one is more likely to remember the day of the week than the date, the letter is more likely to have been written on the 15th than the 16th.

- 3

the one yesterday was such a wretched scrapColette identified the scrappy letter as one that began “My Beloved, another dusty and footsore day.” It is undated and follows a letter dated 13 August, which is equally scrappy and in fact begs forgiveness for “this scrap” (BRACERS 113148 and 113149).

- 4

7 weeks that remain That is, until 2 October, BR’s expected early date of release for good conduct and industry.

- 5

tortured by jealousy “While I was in prison, I was tormented by jealousy the whole time, and driven wild by the sense of impotence” (Auto. 2: 37). From this letter until about 28 August (Letter 86), BR suffered greatly from jealousy. This could be the period to which he referred in writing “When I first had occasion to feel it <jealousy>, it kept me awake almost the whole of every night for a fortnight, and at the end I only got sleep by getting a doctor to prescribe sleeping-draughts” (Auto. 2: 37).

- 6

then Rinders’Miss Rinder offered her family’s cottage as a place to stay once BR left prison. Windmill Cottage was in Icklesham, near Winchelsea. Although not on the coast, it was not far away.

- 7

after Blackpool The film Hindle Wakes was shot in and near Blackpool in September 1917. BR became very jealous of Colette’s relationship with her director, Maurice Elvey, and this jealousy caused a serious rift with her.

- 8

It is a blow that Miles is coming 2 nights a week to R.C.Miles Malleson was at the rather grim Studio. Colette may have told BR about this during a visit; there is nothing about it in her extant letters. Colette had just found a new flat for her sister Clare who had been living at Russell Chambers. Colette was still living in the Attic, which she shared with Miles, although Elizabeth Russell had recently agreed to take on the Attic (“Letters to Bertrand Russell from Constance Malleson, 1916–1969”, p. 264; in RA). Why “it is a blow” to BR is not at all clear.

- 9

letter to Helen Dudley An American from Chicago with whom BR became involved during his 1914 trip to the United States. She followed him back to London, was rebuffed by him, and ended up renting his Bury Street flat in late 1916 or early 1917. In May 1918 she sublet the flat to Clare Annesley. Colette delivered the letter (unread, she said at BRACERS 113151) to Dudley at her club on 19 August. Dudley replied devastatingly to BR the same day before she sailed for America (BRACERS 76545).

- 10

thank Miss Rinder for lettersShe wrote BR on 6 August 1918 (BRACERS 79628), 8 August (BRACERS 79624), again probably on the 8th (BRACERS 79622), and then 9 August (BRACERS 79625).

- 11

tell Ly. O. … seeing her As BR himself explained to Ottoline in Letter 75. See note 3 in that letter for Ottoline’s account of perhaps the same event in her memoirs.

- 12

Various letters in other places That is, concealed in other uncut pages of the camouflage book or journal.

- 13

my brother had succeeded with CaveFrank was trying to shorten the time that BR had to serve by appealing to Sir George Cave, who had been Home Secretary since 1916 (see, e.g. Letters 52, 61 and 62). Frank’s most recent ploy had been to send Cave one of BR’s own letters (Letter 67). But what BR described to Colette as “a very dignified solemn letter”, which asserted the importance of his new philosophical research, was not favourably received by the Home Office (see Letter 69, note 5).

- 14

“Madge” The character of Madge was one of three parts Colette began to prepare for the Experimental Theatre (BRACERS 113156). She asked BR to return the “script of ‘Madge’” (which was by Miles Malleson) in her letter of 2 September (BRACERS 113155).

- 15

Paterne Berrichon on Rimbaud Probably Jean-Arthur Rimbaud, le poète (1854–1873) (Paris: Mercure de France, 1912). A letter from Gladys Rinder (15 June 1918, BRACERS 79614) contained a message from Ottoline that BR should keep the Rimbaud. If this was the book that was under discussion in June, then Ottoline had changed her mind — doubtless because BR had told her he had no liking for Rimbaud (Letters 27 and 31). See also Letter 70.

- 16

C.A. … Gretna GreenClifford Allen, often referred to as “C.A.”, was supposed to be in Cumberland with Catherine Marshall. Since he was not, BR impishly suggested Gretna Green, the border-village in Scotland where English couples went to marry quickly.

- 17

2 guineas a weekColette had asked what the rent would be at BR’s Bury Street flat, where she was going to move.

- 18

about spare room Whatever Colette suggested to him at this time about the spare room at the Bury Street flat is not extant in her “Letters to Bertrand Russell from Constance Malleson, 1916–1969” (typescript in RA). However, on 24 August 1918 he wrote her that making the little room into a sitting-room with books would be a great improvement (Letter 81).

Textual Notes

- a

for the present. Before an obliterated sentence.

- b

I have never … jealousy of Miles. Inserted above the above obliterated sentence.

- c

flat of your own. Before an obliterated sentence.

- d

(I would rather you read it.) Inserted.

- e

Sep Inserted above deleted “Oct”.

- f

I was tired … bewilderment. Inserted.

- g

Various letters Before deleted “from various people”.

- h

“Madge” Quotation marks editorially supplied.

- i

2 guineas a week … I should wish. The paragraph was written in the top margin.

Boismaison

Colette and BR vacationed at a house, The Avenue, owned by Mrs. Agnes Woodhouse and her husband, in the countryside near Ashford Carbonel, Shropshire, in August 1917. They nicknamed the house “Boismaison”. Agnes Woodhouse took in paying guests. Their first visit was idyllic. They returned for other vacations — in 1918 before he entered prison and in April 1919. Their plan to go soon after he got out of prison failed because their relationship faltered for a time. They discussed returning in the summer of 1919 — a booking was even made for 12–19 July — but in the end they didn’t go. See S. Turcon, “Then and Now: Bertie and Colette’s Escapes to the Peak District and Welsh Borderlands”, Russell 34 (2014): 117–30.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Catherine E. Marshall

Catherine E. Marshall (1880–1961), suffragist and internationalist who after August 1914 quickly moved from campaigning for women’s votes to protesting the war. An associate member of the No-Conscription Fellowship, she collaborated closely with BR during 1917 especially, when she was the organization’s Acting Hon. Secretary and he its Acting Chairman. Physically broken by a year of intense political work on behalf of the C.O. community, Marshall then spent several months convalescing with the NCF’s founding chairman, Clifford Allen, after he was released from prison on health grounds late in 1917. According to Jo Vellacott, Marshall was in love with Allen and “suffered deeply when he was imprisoned”. During his own imprisonment BR heard rumours that Marshall was to marry Allen (e.g., Letter 71), and Vellacott further suggests that the couple lived together during 1918 “in what seems to have been a trial marriage; Marshall was devastated when the relationship ended” (Oxford DNB). Throughout the inter-war period Marshall was active in the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

Clifford Allen

(Reginald) Clifford Allen (1889–1939; Baron Allen of Hurtwood, 1932) was a socialist politician and publicist who joined the Cambridge University Fabian Society while studying at Peterhouse College (1908–11). After graduating he became active in the Independent Labour Party in London and helped establish a short-lived labour newspaper, the Daily Citizen. During the war Allen was an inspiring and effective leader of the C.O. movement as chairman of the No-Conscription Fellowship, which he co-founded with Fenner Brockway in November 1914. Court-martialled and imprisoned three times after his claim for absolute exemption from war service was rejected, Allen became desperately ill during his last spell of incarceration. He was finally released from the second division of Winchester Prison on health grounds in December 1917, but not before contracting the tuberculosis with which he was finally diagnosed in September 1918. He was dogged by ill health for the rest of his life. BR had enormous affection and admiration for Allen (e.g., 68 in Papers 13, 46 in Papers 14), a trusted wartime political associate. From February 1919 until March 1920 he even shared Allen’s Battersea apartment. A close friendship was soured, however, by Allen’s rejection of BR’s unforgiving critique of the Bolshevik regime, which both men witnessed at first hand with the British Labour Delegation to Russia in May 1920 (see Papers 15: 507). Yet Allen was far from revolutionary himself and did not even identify with the left wing of the ILP (which he chaired in the early 1920s). He was elevated to the peerage as a supporter of Ramsay MacDonald’s National Government, an administration despised by virtually the entire labour movement. Although Allen’s old intimacy with BR was never restored after the Russia trip, any lingering estrangement did not inhibit him from enrolling his daughter, Joan Colette (“Polly”) at the Russells’ Beacon Hill School.

Elizabeth Russell

Elizabeth Russell, born Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941), was a novelist who in 1891 married Graf von Arnim-Schlagenthin. She became known as “Elizabeth”, the name she used in publishing Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898), and she remained widely known as Elizabeth von Arnim, although the Library of Congress catalogues her as Mary Annette (Beauchamp), Countess von Arnim. She was a widow when she married BR’s brother, Frank, on 11 February 1916. The marriage was quickly in difficulty; she left it for good in March 1919, but they were never divorced and she remained Countess Russell (becoming Dowager Countess after Frank’s death in 1931).

Experimental Theatre

Colette first mentioned that she and Miles were trying to start an Experimental Theatre in a letter of 24 June 1918 (BRACERS 113135), indicating that Miles would earn a tiny income from it. About a month later, she wrote that Elizabeth Russell had subscribed generously to the Theatre and that £700 had been raised, but hundreds still had to be found (BRACERS 113146). A few days later she wrote that Captain Stephen Gordon, a north-country lawyer working for the government, was to be the honorary treasurer, noting that he had “put most of the drive into the whole thing” (BRACERS 113147). During August Colette was happy with her involvement with the Theatre (Letter 68). John Galsworthy came to tea to discuss the project (c.14 Aug., BRACERS 113149). On 2 September she listed the members of the Theatre committee as “Desmond <MacCarthy>, Massingham, Galsworthy, and Dennis (Bradley)” (BRACERS 113155). The following day she wrote that she was learning three parts (BRACERS 113156). In her memoirs, Colette wrote about the “Experimental Little Theatre” but dated it 1919 (After Ten Years [London: Cape, 1931], pp. 129–30). An “artistic” theatre did get founded in 1920 in Hampstead, and John Galsworthy was connected to that venture, The Everyman Theatre — he was part of a reading committee which chose the works to be performed (The Times, 9 Sept. 1919, p. 8). The Everyman Theatre was under the direction of Norman MacDermott. In his book Everymania (London: Society for Theatre Research, 1975), he noted that he met Miles in the summer of 1918: they rented a store in Bloomsbury, had a cabinetmaker build sets, and put on plays with actors “bored with West-End theatres” (p. 10). It is likely that the Everyman Theatre was an out-growth of the Experimental Theatre.

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Home Secretary / Sir George Cave

Sir George Cave (1856–1928; Viscount Cave, 1918), Conservative politician and lawyer, was promoted to Home Secretary (from the Solicitor-General’s office) on the formation of the Lloyd George Coalition in December 1916. His political and legal career peaked in the 1920s as Lord Chancellor in the Conservative administrations led by Andrew Bonar Law and Stanley Baldwin. At the Home Office Cave proved to be something of a scourge of anti-war dissent, being the chief promoter, for example, of the highly contentious Defence of the Realm Regulation 27C (see Letter 51).

J.E. Littlewood

John Edensor Littlewood (1885–1977), mathematician. In 1908 he became a fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, and remained one for the rest of his life. In 1910 he succeeded Whitehead as college lecturer in mathematics and began his extraordinarily fruitful, 35-year collaboration with G.H. Hardy. During the First World War he worked on ballistics for the British Army. He and BR were to share Newlands farm, near Lulworth, during the summer of 1919. Littlewood had two children, Philip and Ann Streatfeild, with the wife of Dr. Raymond Streatfeild.

Lucy Silcox

Lucy Mary Silcox (1862–1947), headmistress of St. Felix school in Southwold, Suffolk (1909–26), feminist, and long-time friend of BR’s, whom he had known since at least 1906. On a letter from her, he wrote that she was “one of my dearest friends until her death ” (BR’s note, BRACERS 80365). After learning of BR’s conviction and sentencing by the Bow St. magistrate, a distraught Silcox reported to him that she had been “shut out in such blackness and desolation” (2 Feb. 1918, BRACERS 80377). During BR’s imprisonment it was Silcox who brought to his attention the Spectator review of Mysticism and Logic. Years later (in 1928), when BR and Dora Russell had launched Beacon Hill School, Silcox came with Ottoline Morrell to visit it.

Maurice Elvey

Maurice Elvey (1887–1967) was a prolific film director (of silent pictures especially) and enjoyed a very successful career in that industry lasting many decades. Born William Seward Folkard into a working-class family, Elvey changed his name around 1910, when he was acting. He directed his first film, The Fallen Idol, in 1913. By 1917, when he directed Colette in Hindle Wakes, he had married for a second time — to a sculptor, Florence Hill Clarke — his first marriage having ended in divorce. Elvey and Colette had an affair during the filming of Hindle Wakes, beginning in September 1917, which caused BR great anguish. In addition to his feeling of jealousy during his imprisonment, BR was worried over the rumour that Elvey was carrying a dangerous sexually transmitted disease. (See BR, “My First Fifty Years”, RA1 210.007050–fos. 127b, 128, and Monk, 2: 507). Colette later maintained that Elvey cleared himself (“Letters to Bertrand Russell from Constance Malleson, 1916–1969”, p. 154, typescript, RA). BR removed the allegation from the Autobiography as published (see 2: 37), but he remained fearful. After Elvey’s long-lost wartime film about the life of Lloyd George was rediscovered and restored in the 1990s, it premiered to considerable acclaim (see Letter 87, note 12).

Miles Malleson

Miles Malleson (1888–1969), actor and playwright, was born in Croydon, Surrey, the son of Edmund and Myrrha Malleson. He married his first wife, a fellow actor, Lady Constance Annesley (stage name, Colette O’Niel), in 1915. They had met at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts). Their marriage was an “open” one. In 1914 Miles enlisted in the City of London Fusiliers and was sent to Malta. He became ill and was discharged, unfit for further service. He became active in the No-Conscription Fellowship and wrote anti-war stage plays as well as a pamphlet, Cranks and Commonsense (1916). In the 1930s he began to write for the screen and act in films, in which he became a very well-known character actor, as well as continuing his stage career at the Old Vic in London. He married three times: his second marriage was to Joan Billson, a physician (married 1923, divorced 1940), with whom he had two children; his third wife was Tatiana Lieven, an actress (married 1946). He died in London in March 1969.

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

Russell Chambers

34 Russell Chambers, Bury Street (since renamed Bury Place), London WC1, BR’s flat since 1911. Helen Dudley rented the flat in late 1916 or early 1917. In May 1918 she sublet it to Clare Annesley. Colette moved in on 9 September 1918 and stayed until June 1919. BR did not give up the lease until December 1923. See S. Turcon, “Russell Chambers, Other London Flats, and Country Homes, 1911–1923”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 150 (Fall 2014): 30–4. “Russell Chambers, Other London Flats, and Country Homes, 1911–1923”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 150 (Fall 2014): 30–4.

The Attic

The Attic was the nickname of the flat at 6 Mecklenburgh Square, London WC1, rented by Colette and her husband, Miles Malleson. The house which contained this flat is no longer standing. “The spacious and elegant facades of Mecklenburgh Square began to be demolished in 1950. The houses on the north side were banged into dust in 1958. The New Attic was entirely demolished” (“Letters to Bertrand Russell from Constance Malleson, 1916–1969”, p. 109; typescript in RA).

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.