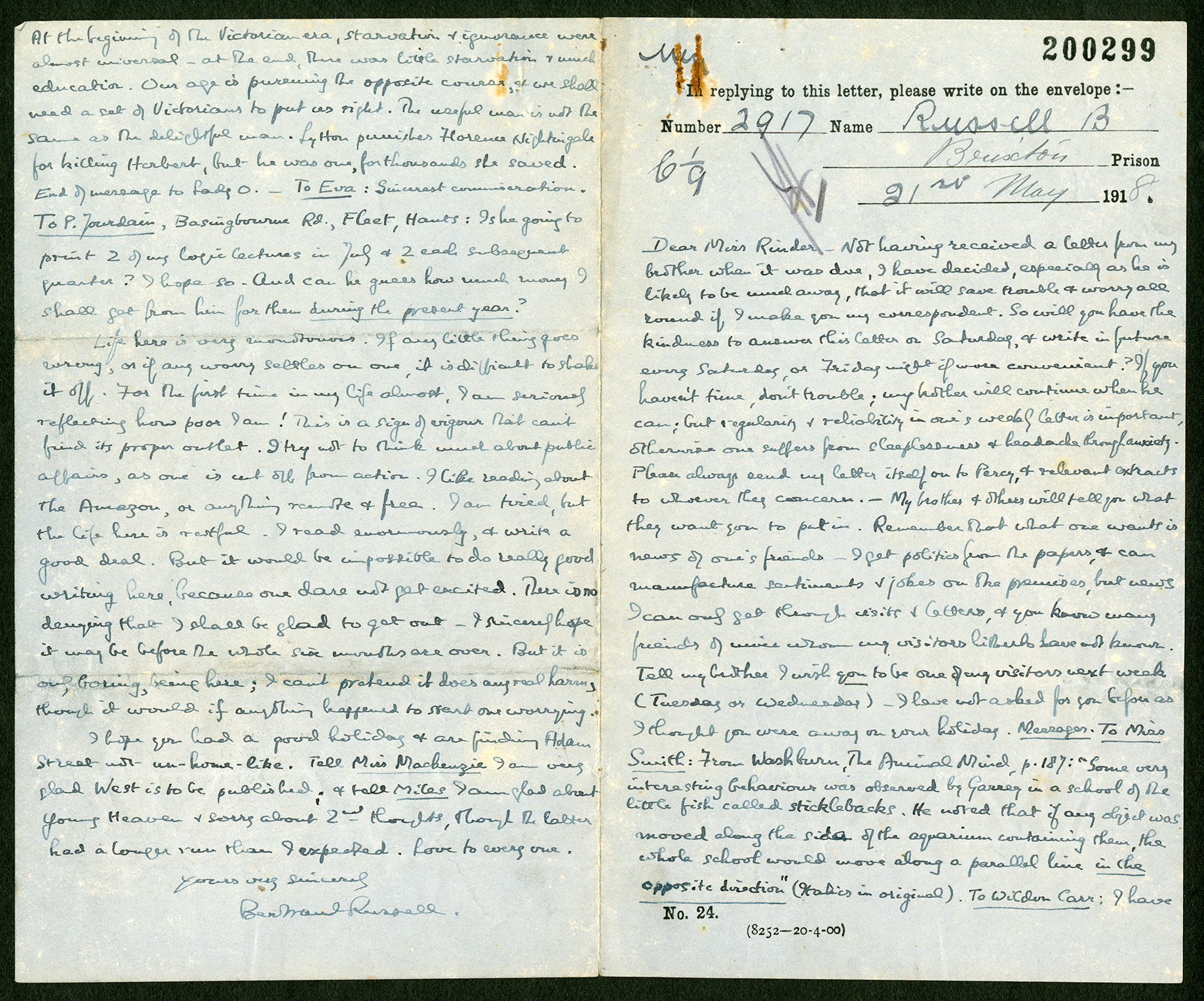

Brixton Letter 7

BR to Gladys Rinder

May 21, 1918

- ALS

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-7SLBR 2: #313

BRACERS 19307

Number 2917 Name Russell B.1

Brixton Prison

21st May 1918.

Dear Miss Rinder

Not having received a letter from my brother when it was due, I have decided, especially as he is likely to be much away, that it will save trouble and worry all round if I make you my correspondent.2 So will you have the kindness to answer this letter on Saturday,3 and write in future every Saturday, or Friday night if more convenient? If you haven’t time, don’t trouble; my brother will continue when he can; but regularity and reliability in one’s weekly letter is important, otherwise one suffers from sleeplessness and headache through anxiety. Please always send my letter itself on to Percy,4 and relevant extracts to whoever they concern. — My brother and others will tell you what they want you to put in. Remember that what one wants is news of one’s friends — I get politics from the papers, and can manufacture sentiments and jokes on the premises, but news I can only get through visits and letters, and you know many friends of mine whom my visitors5 hitherto have not known. Tell my brother I wish you to be one of my visitors next week (Tuesday or Wednesday) — I have not asked for you before as I thought you were away on your holiday. Messages. To Miss Smith:6 From Washburn,7 The Animal Mind, p. 187: “Some very interesting behaviour was observed by Garrey in a school of the little fish called sticklebacks.8 He noted that if any object was moved along the side of the aquarium containing them, the whole school would move along a parallel line in the opposite direction” (Italics in original). To Wildon Carr: I have asked leave to see him and to send him MSS. but have not yet had any reply. He might perhaps approach H.O.9 I have written about 20,000 words of Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy,10 to follow lines of lectures before Xmas. Shall then work over lectures after Xmas (which I have, thanks).11 For the moment, shall probably not attempt to write on “Analysis of Mind”, but to read and think. Thanks for number of Psychological Review:12, a read with great interest. No behaviourist so far as I can discover tackles any of the difficult parts of his problem. If any of them have written intelligently on analysis of belief,13 I wish to read them. Hope finish Introduction in another month or so. Prison is all right for reading and easy work, but would be impossible for really difficult thinking. All this is equally to Whitehead.

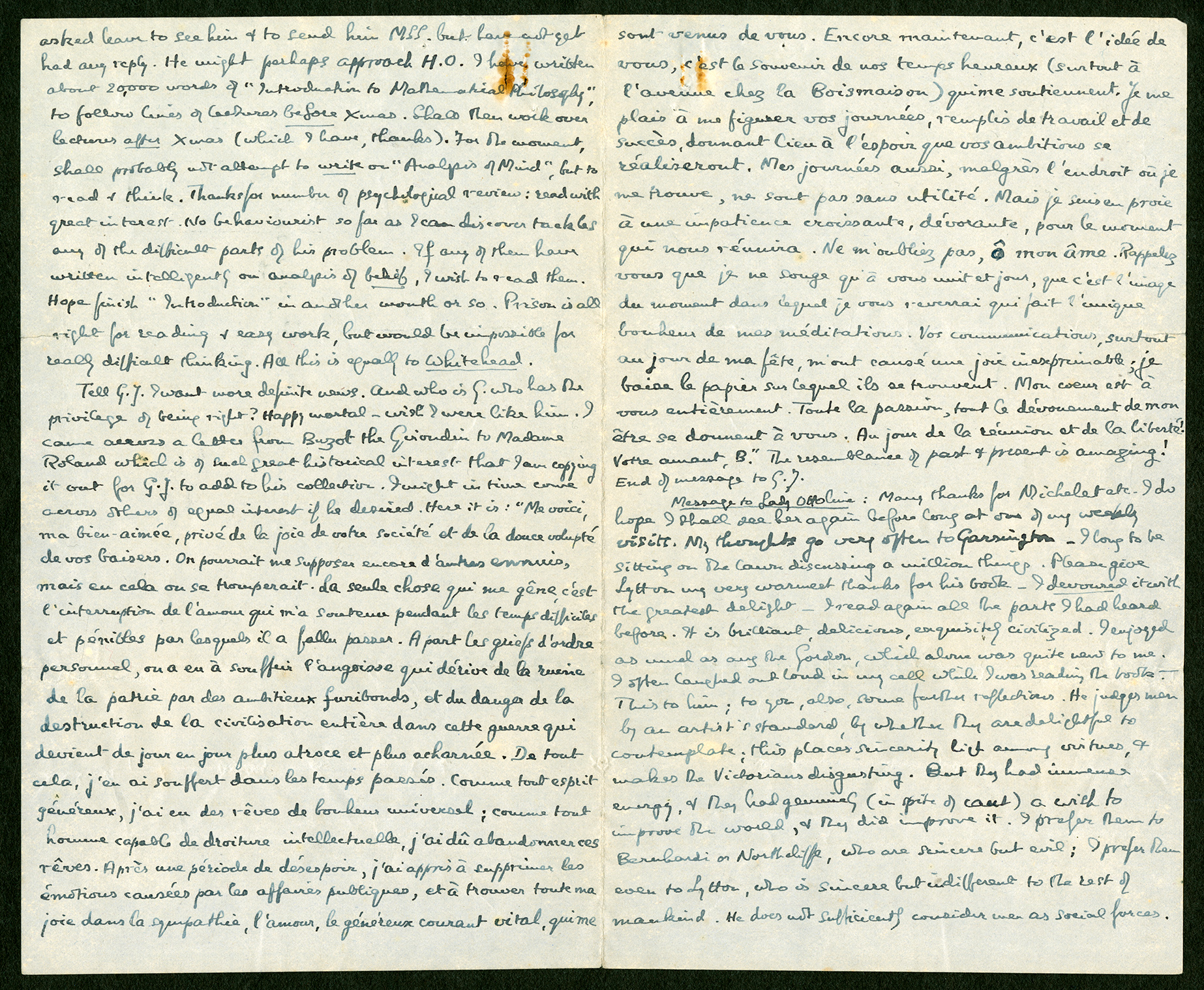

Tell G.J.14 I want more definite news. And who is G.15 who has the privilege of being right? Happy mortal — wish I were like him. I came across a letter from Buzot the Girondin to Madame Roland16 which is of such great historical interest that I am copying it out for G.J. to add to his collection.17 I might in time come across others of equal interest if he desired. Here it is: “Me voici, ma bien-aimée, privé de la joie de votre société et de la douce volupté de vos baisers. On pourrait me supposer encore d’autres ennuis, mais en cela on se tromperait. La seule chose qui me gêne, c’est l’interruption de l’amour qui m’a soutenu pendant les temps difficiles et pénibles par lesquels il a fallu passer. A part les griefs d’ordre personnel, on a eu à souffrir l’angoisse qui dérive de la ruine de la patrie par des ambitieux furibonds, et du danger de la destruction de la civilisation entière dans cette guerre qui devient de jour en jour plus atroce et plus acharnée. De tout cela, j’en ai souffert dans les temps passés. Comme tout esprit généreux, j’ai eu des rêves de bonheur universel; comme tout homme capable de droiture intellectuelle, j’ai dû abandonner ces rêves. Après une période de désespoir,18 j’ai appris à supprimer les émotions causées par les affaires publiques, et à trouver toute ma joie dans la sympathie, l’amour, le généreux courant vital, qui me sont venus de vous. Encore maintenant, c’est l’idée de vous, c’est le souvenir de nos temps heureux (surtout à l’avenue chez la Boismaison) qui me soutiennent.b Je me plais à me figurer vos journées, remplis de travail et de succès, donnant lieu à l’espoir que vos ambitions se réaliseront. Mes journées aussi, malgrèsc l’endroit où je me trouve, ne sont pas sans utilité. Mais je suis en proie à une impatience croissante, dévorante, pour le moment qui nous réunuira. Ne m’oubliez pas, ȏ mon âme. Rappelez vous que je ne songe qu’à vous nuit et jour, que c’est l’image du moment dans lequel je vous reverrai qui fait l’unique bonheur de mes méditations. Vos communications, surtout au jour de ma fête,19 m’ont causé une joie inexprimable; je baise le papier sur lequel ilsd se trouvent. Mon coeur est à vous entièrement. Toute la passion, tout le dévouement de mon être se donnent à vous. Au jour de la réunion et de la liberté! Votre amant, B.” The resemblance of past and present is amazing! End of message to G.J.

<Translation:>

“Here I am, my beloved, deprived of the joy of your company and of the sweet, sensual pleasure of your kisses. You might suppose I still had other worries, but in that you would be mistaken. The only thing that concerns me is the interruption of the love that has sustained me during the difficult and painful times through which it has been necessary to pass. Apart from personal griefs, one has to suffer the anguish caused by the ruin of the country by ambitious madmen, and of the danger of the destruction of the whole of civilization in this war which becomes daily more atrocious and more fierce. From all that, I have suffered in the past. Like every generous spirit, I had dreams of universal happiness; like every man capable of thinking rightly, I have had to abandon these dreams. After a period of despair, I have learnt to suppress emotions caused by public affairs, and to find all my happiness in sympathy, love, the abundant living stream that has come to me from you. Even now, it is the thought of you, the memory of our happy times (especially the Woodhouses’ Avenue) which sustains me. I delight in imagining your days, filled with work and success, giving room to hope that your ambitions will be realized. My days too, even though I’m not where I want to be, are not without use. But I am tortured by a growing, devouring impatience for the moment that will reunite us. Do not forget me, O my soul. Remember that I dream only of you night and day, that the only happiness in my thoughts is in picturing the moment at which I’ll see you again. Your messages, especially on my birthday, have given me an inexpressible joy; I kiss the paper on which they are found. My heart is entirely yours. All the passion, all the devotion of my being pours out to you. To the day of reunion and freedom! Your lover, B.”

Message to Lady Ottoline: Many thanks for Michelet20 etc. I do hope I shall see her again before long at one of my weekly visits. My thoughts go very often to Garsington — I long to be sitting on the lawn discussing a million things. Please give Lytton my very warmest thanks for his book21 — I devoured it with the greatest delight — I read again all the parts I had heard before. It is brilliant, delicious, exquisitely civilized. I enjoyed as much as any the Gordon, which alone was quite new to me. I often laughed out loud in my cell while I was reading the book. — This to him; to you, also, some further reflections. He judges men by an artist’s standard, by whether they are delightful to contemplate; this places sincerity high among virtues, and makes the Victorians disgusting. But they had immense energy, and they had genuinely (in spite of cant) a wish to improve the world, and they did improve it. I prefer them to Bernhardi22 or Northcliffe, who are sincere but evil; I prefer them even to Lytton, who is sincere but indifferent to the rest of mankind. He does not sufficiently consider men as social forces. At the beginning of the Victorian era, starvation and ignorance were almost universal — at the end, there was little starvation and much education. Our age is pursuing the opposite course, and we shall need a set of Victorians to put us right. The useful man is not the same as the delightful man. Lytton punishes Florence Nightingale for killing Herbert,23 but he was one, for thousands she saved. End of message to Lady O. — To Eva: Sincerest commiseration.24To P. Jourdain, Basingbourne Rd., Fleet, Hants: Is he going to print 2 of my logic lectures25 in July and 2 each subsequent quarter? I hope so. And can he guess how much money I shall get from him for them during the present year?26

Life here is very monotonous. If any little thing goes wrong, or if any worry settles on one, it is difficult to shake it off. For the first time in my life almost, I am seriously reflecting how poor I am! This is a sign of vigour that can’t find its proper outlet. I try not to think much about public affairs, as one is cut off from action. I like reading about the Amazon,27 or anything remote and free. I am tired, but the life here is restful. I read enormously, and write a good deal. But it would be impossible to do really good writing here, because one dare not get excited. There is no denying that I shall be glad to get out — I sincerely hope it may be before the whole six months are over. But it is only boring, being here; I can’t pretend it does any real harm, though it would if anything happened to start one worrying.

I hope you had a good holiday and are finding Adam Street not un-home-like.28 Tell Miss Mackenzie I am very glad West is to be published;29 and tell Miles I am glad about Young Heaven30 and sorry about 2nd Thoughts,31, e though the latter had a longer run than I expected. Love to every one.

Yours very sincerely

Bertrand Russell.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the signed original in BR’s handwriting in the Russell Archives. On the blue correspondence form of the prison system, it consists of a single sheet folded once vertically and twice horizontally; all four sides are filled. Particulars, such as BR’s name and number, were entered in an unknown hand. Prisoners’ correspondence was subject to the approval of the governor or his deputy. This letter has “HB” (for an unidentified deputy of the governor) handwritten at the top, making it an “official” letter. The letter was published as #313 in Vol. 2 of BR’s Selected Letters.

- 2

make you my correspondent BR was allowed to receive and send one official letter per week. The first two (Letters 2 and5) had been written to Frank Russell.

- 3

answer this letter on SaturdayRinder did so (25 May 1918, BRACERS 79611).

- 4

Percy BR identified “Percy” on a note on document .079967, BRACERS 116566: “Another pseudonym for Colette.” “Percy” was a nickname used by Colette’s family and which she continued to use in family correspondence decades later.

- 5

my visitors BR was restricted to one personal visit of three people for half an hour once a week, every Tuesday or Wednesday. Business visits were less restrictive.

- 6

Miss Smith Probably Lydia Smith, a Quaker schoolteacher who was editing The Tribunal.

- 7

Washburn M.F. Washburn’s The Animal Mind: a Text-Book of Comparative Psychology (1908) was among the many books on psychology BR read in prison.

- 8

sticklebacks The passage about sticklebacks is an inside joke arising from BR’s appeal. His counsel, Tindal Atkinson, KC, had pointed out that a letter criticizing America’s war effort had been published in The Times, yet it had not been prosecuted. According to “Our Prosecution”, The Tribunal (no. 107 [9 May 1918]: 2), he said that “It appeared like a case of catching the minnow and letting the whale go free. He thought perhaps the word ‘minnow’ was hardly the right one — he might almost have said ‘stickleback’. This remark caused great amusement in court, as some present thought he was referring to Mr. Russell.” A much fuller report appeared as “Mr. Bertrand Russell’s Appeal”, Common Sense, 4 May 1918, p. 225, which continued Atkinson’s speech on the questionable importance given to prosecuting BR: “They thought this was an occasion which would justify the intervention of the Director of Public Prosecutions and the appearance of my learned friend, who is a junior counsel of the Treasury, for the purpose of conducting this prosecution.”

- 9

H.O. The Home Office, which was ultimately responsible for prison governance, although most administrative duties fell inside the remit of the Prison Commission, a statutory board created in 1877.

- 10

Introduction to Mathematical PhilosophyA popular account, published by Allen & Unwin in 1919, of the main doctrines put forward in BR and Whitehead’s Principia Mathematica (1910–13). Written in prison, it was based on a series of public lectures, “The Philosophy of Mathematics”, BR had given in London between 30 October and 18 December 1917.

- 11

(which I have, thanks) These were his lectures on “The Philosophy of Logical Atomism”, which were published in four installments in The Monist (Oct. 1918 to July 1919; 17 in Papers 8). The lectures were delivered extempore, taken down by a stenographer and transcribed, and the typescript sent (presumably after correction by BR) to America for publication before BR went to jail. Later in the current letter BR asked if Jourdain, The Monist’s English editor, was planning to start publication in the July issue. BR did not see proofs from The Monist. What he had in prison was no doubt a copy of the typescript (next year he told Unwin he believed he had kept a duplicate [BRACERS 47470]) for the purpose of working it up into a book, described in Letter 9 (see note 20) as “Elements of Logic”, which would situate logic in relation to psychology and mathematics and “set forth [the] logical basis of what I call ‘logical atomism’”. BR did not turn to this task once he had completed the Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy because of changes in his philosophy which took place while he was in prison. Propositions, which had previously been eliminated from his philosophy, were reinstated, but as psychological rather than purely logical entities. This changed BR’s view of the relation between logic and psychology and made it necessary to treat psychological matters (work which eventually appeared as “On Propositions: What They Are and How They Mean” [1919; 20 in Papers 8] and The Analysis of Mind [1921]) before tackling “Elements of Logic”. The latter work, alas, was never written.

- 12

Psychological Review In prison BR read several articles from volumes 18–23 (1911–16) of The Psychological Review. See Papers 8: 326–8 for a list of his philosophical prison-reading.

- 13

analysis of beliefIn Letter 5 BR mentioned belief as one of three main problems he encountered as he attempted to give an account of mind from a largely behaviourist standpoint. It was the most pressing of the three since BR had abandoned his previous theory of belief, the multiple-relation theory, in the face of Wittgenstein’s criticisms in 1913.

- 14

G.J. One of the pseudonyms used by Colette. G.J. began to communicate with BR via Personals in The Times before the method of smuggling letters in the uncut pages of books was devised. When this letter was written Colette had placed five messages in The Times: 7 May 1918 (BRACERS 96064), 9 May (BRACERS 96078), 13 May (BRACERS 96079), 14 May (BRACERS 96080), and 18 May (BRACERS 96081).

- 15

who is G. The message that Colette placed in The Times on 13 May — “G is right. Happy beyond words. Work improving too. Earning extra £2 week.” — proved too cryptic for BR, yet she was probably echoing the saying of Goethe’s that BR quoted in Letter 2.

- 16

Buzot the Girondin to Madame Roland François Nicolas Léonard Buzot (1760–1794), a far-left Girondin deputy in the French National Assembly. His love affair with Madame Roland (née Marie-Jeanne Philipon, 1754–1793) started in 1792, a few months before she was arrested and he had to flee for his life. They smuggled letters to each other while she was in jail and he in hiding. He committed suicide to avoid arrest six months after she was executed.

- 17

letter from Buzot… collection From York, where she was acting with a touring company, Colette acknowledged receipt of a fictional “Buzot” letter on 31 May 1918 (BRACERS 113133), calling it “greatly treasured” but indicating she was not sure if BR had received an early message she had sent about it. There were two more fictional letters from Buzot to Madame Roland (Letters 8 and 10); Colette made no distinction between these letters in her acknowledgement. What follows in the text is really a love letter from BR to Colette.

- 18

une période de désespoir Probably the period described by BR over Christmas and New Year’s 1916–17 (Auto. 2: 27). He expressed his despair in “Why Do Men Persist in Living?” (1917; 3 in Papers 14).

- 19

surtout au jour de ma fête The birthday message in The Times, 18 May 1918, p. 3, col. 2, was: “G.J. — many happy returns today. Very busy. All loving thoughts with you. Bless you” (BRACERS 96081).

- 20

Michelet Probably Jules Michelet’s Histoire de la révolution française (7 vols., 1847–53).

- 21

Lytton … book The author of Eminent Victorians (1918) had read parts of his new book to friends (including BR) at Garsington. In jail BR read Strachey’s most famous historical work with so much amusement that the warder came to his cell to remind him that “prison is a place of punishment” (Auto. 2: 34). On 1 June 1918, Ottoline reported to BR that Strachey regarded it as “a great honour that my book should have made the author of Principia Mathematica laugh aloud in Brixton Gaol” (BRACERS 114746).

- 22

Bernhardi General Friedrich Adam Julius von Bernhardi (1849–1930), an extreme Prussian militarist. In 1912 he published Deutschland und der nächste Krieg (translated as Germany and the Next War [1914]) which advocated German expansion through wars with France, Britain, and Russia.

- 23

punishes Florence Nightingale for killing Herbert As Secretary at War (a junior ministerial office responsible for army affairs but not military policy) during the Crimean War, Whig statesman Sidney Herbert (1810–1861) appointed professional nurse and social reformer Florence Nightingale (1820–1910) to oversee the medical treatment of British troops in Scutari. The two were already confidantes and developed a conviction that both army health and the entire War Office administration required a radical overhaul. Promoted to Secretary of State for War at the start of Lord Palmerston’s second ministry in 1859, Herbert endeavoured to implement his and Nightingale’s ambitious reform agenda. Afflicted with Bright’s disease, however, his frail health was broken by War Office obstruction of his plans and (according to Strachey) Nightingale’s relentless badgering. He died shortly after being elevated to the peerage as Baron Herbert of Lea (he was also a son of the 11th Earl of Pembroke). See Eminent Victorians (London: Chatto & Windus, 1918; Russell’s library), pp. 162–5.

- 24

To Eva: Sincerest commiseration BR was referring to her letter of 13 May 1918 (BRACERS 1855), where she wrote about how she was trying to look after parcels of books for him while in a hurry and running late.

- 25

my logic lectures The lectures BR referred to here were “The Philosophy of Logical Atomism” (B&R C18.07), mentioned in his message to Wildon Carr. The Monist, which Jourdain co-edited, didn’t start publishing them until October 1918; they did proceed at the rate of two per quarterly issue. BR did not see proofs. “The verbatim reports”, he told Unwin on 23 March 1919, “were sent to America before I went to prison, and though I believe I kept a duplicate, I have not seen them since” (BRACERS 47470).

- 26

how much money I shall get from him for them Frank replied on 31 May with Jourdain’s response: “We will I think print two of the articles in each number. I cannot tell whether they will begin in July but Carus is pleased with them. If 4 appear in July and October, about £60 will be paid” (BRACERS 46916). In fact, BR got nothing for the articles in 1918. Open Court’s owner, Paul Carus (1852–1919), died the next February, and Jourdain told BR repeatedly he should not bother Mrs. Carus about payment for the time being. Jourdain died in October. BR was finally paid the sum of £245.2.0 in December 1919, presumably for all eight articles.

- 27

I like reading about the AmazonOttoline had lent him H.M. Tomlinson, The Sea and the Jungle (1912). For more on the book, see Letter 9.

- 28

Adam Street not un-home-likeRinder worked for the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau at 11 Adam Street, off the Strand in the City of Westminster. On 25 May, however, she told BR that she would be leaving Adam St. as of 1 June to assume “new duties” (BRACERS 79611) at the NCF’s main office at 5 York Buildings, Adelphi. It is not clear how her role changed, but a few days later she reported to BR (via Frank) that she was not happy “working at Y.B. <York Buildings> under E.E.H. <Hunter>. Feel useless but must give it a trial” (6 June 1918, BRACERS 46918).

- 29

Tell Miss Mackenzie … glad West is to be publishedDorothy Cousens (née Mackenzie) had been the fiancée of Lieut. A. Graeme West (1891–1917). The Diary of a Dead Officer, a collection of his letters and memorabilia edited by Cyril Joad, was published in 1918 by Allen & Unwin.

- 30

Young Heaven A one-act tragedy by Miles Malleson and Jean Cavendish about a touring actress whose brother has been killed in the war. The play, with Colette in the lead role as Daphne, was put on in Oxford in 1919 and again in Hull in 1925. It was published by Allen & Unwin in 1918. Bennitt Gardiner, who followed Colette’s career closely, thought it one of her best roles (“Colette O’Niel: a Season in Repertory”, Russell, o.s. nos. 23–4 [autumn–winter 1976]: 31–2).

- 31

sorry about 2nd ThoughtsMiles Malleson, Second Thoughts, a booklet on World War I and his eventual C.O. status, was published in 1917 by the National Labour Press, Manchester. It was banned, though not as quickly as BR expected, which explains the reference to its “longer run”. Colette had communicated in a letter from Frank to BR, 7 May 1918 (BRACERS 46912), using the name “Percy”: “Second Thoughts has gone the way of Black ’Ell.” The book, ‘D’ Company and Black ’Ell: Two Plays by Miles Malleson, was published by Hendersons in November 1916. Almost immediately the book was seized from the publishers under the Defence of the Realm Act (Constance Malleson, After Ten Years [London: Cape, 1931], p. 110).

Textual Notes

A.N. Whitehead

Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947), Cambridge-educated mathematician and philosopher. From 1884 to 1910 he was a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, and lecturer in mathematics there; from 1911 to 1924 he taught in London, first at University College and then at the Imperial College of Science and Technology; in 1924 he took up a professorship in philosophy at Harvard and spent the rest of his life in America. BR took mathematics courses with him as an undergraduate, which led to a lifelong friendship. Whitehead’s first major work was A Treatise on Universal Algebra (1898), which treated selected mathematical theories as “systems of symbolic reasoning”. Like BR’s The Principles of Mathematics (1903), it was intended as the first of two volumes; but in 1900 he and BR discovered Giuseppe Peano’s work in symbolic logic, and each decided to set aside his projected second volume to work together on a more comprehensive treatment of mathematics using Peano’s methods. The result was the three volumes of Principia Mathematica (1910–13), which occupied the pair for over a decade. After Principia was published, Whitehead’s interests, like BR’s, turned to the empirical sciences and, finally, after his move to America, to pure metaphysics. See Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: the Man and His Work, 2 vols. (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins U. P., 1985–90).

Boismaison

Colette and BR vacationed at a house, The Avenue, owned by Mrs. Agnes Woodhouse and her husband, in the countryside near Ashford Carbonel, Shropshire, in August 1917. They nicknamed the house “Boismaison”. Agnes Woodhouse took in paying guests. Their first visit was idyllic. They returned for other vacations — in 1918 before he entered prison and in April 1919. Their plan to go soon after he got out of prison failed because their relationship faltered for a time. They discussed returning in the summer of 1919 — a booking was even made for 12–19 July — but in the end they didn’t go. See S. Turcon, “Then and Now: Bertie and Colette’s Escapes to the Peak District and Welsh Borderlands”, Russell 34 (2014): 117–30.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.

Dorothy Cousens

Dorothy Cousens (née Mackenzie) had been the fiancée of Graeme West, a soldier who had written to BR from the Front about politics. The Diary of a Dead Officer, a collection of his letters and memorabilia edited by Cyril Joad, was published in 1918 by Allen & Unwin. BR got to know Mackenzie after West was killed in action in April 1917 (she, “on the news of his death, became blind for three weeks” [BR’s note, Auto. 2: 71]) and provided some work for her and the man she married, Hilderic Cousens. Decades later she explained to K. Blackwell how she knew BR: “I had a break-down when most of my generation were either killed or in prison and Bertrand Russell was kind and helped me back to sanity” (29 July 1978, BRACERS 121877). She donated Letter 63 and a much later handwritten letter (BRACERS 55813), on the death of Hilderic, to the Russell Archives.

Eva Kyle

Eva Kyle ran a typing service. She did work for the No-Conscription Fellowship and took BR’s dictation of his book, Roads to Freedom, in the early months of 1918. He annotated a letter from her: “She was an admirable typist but very fat. We all agreed that she was worth her weight in gold, though that was saying a great deal.” Her prison letter to him is clever and amusing. She typed his major prison writings and apologized for the amount of the invoice when he emerged.

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

H. Wildon Carr

Herbert Wildon Carr (1857–1931), Professor of Philosophy at King’s College, London, from 1918 and Visiting Professor at the University of Southern California from 1925. Carr came to philosophy late in life after a lucrative career as a stockbroker. His philosophy was an idiosyncratic amalgam of Bergsonian vitalism and Leibnizian monadology, which, he thought, was supported by modern biology and the theory of relativity. He wrote books on Bergson and Leibniz at opposite ends of his philosophical career and a book on relativity in the middle. His philosophy would have made him an unlikely ally of BR’s, but it was Carr who organized BR’s two courses of public lectures, on philosophy of mathematics and the philosophy of logical atomism, which brought BR back to philosophy and improved his finances in 1917–18. Carr had great administrative talents, which he employed also on behalf of the Aristotelian Society during his long association with it. He was its president in 1916–18 and continued to edit its Proceedings until 1929.

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Joseph Johann Wittgenstein (1889–1951), one of the most influential philosophers of the twentieth century. Austrian born, he abandoned a career in engineering to study philosophy of mathematics with BR at Cambridge in 1911 and started making original contributions, in the form of cryptic, posthumously published notes, shortly thereafter. In 1913 he criticized BR’s multiple-relation theory of judgment so effectively that BR abandoned the book (Theory of Knowledge) presenting the theory. During the First World War he served in the Austrian Army and completed the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (published in German as Logisch-philosophische Abhandlung in 1921 and in English translation under the title by which it became known in 1922), the only major work he published in his lifetime. He then abandoned philosophy for some years before returning to Cambridge in 1929, where he became a Research Fellow and began lecturing. He succeeded G.E. Moore as Knightbridge Professor of Philosophy in 1939. During this later period his philosophy took a very different direction from the one found in the Tractatus. He published nothing but wrote copiously; his notes, lectures, and remarks were posthumously published by his students and disciples in various editions and compilations, the most important of which was Philosophical Investigations (1953). Main biography: Ray Monk, Ludwig Wittgenstein: the Duty of Genius (London: Cape, 1990).

Lytton Strachey

Lytton Strachey (1880–1932), biographer, reviewer and a quintessential literary figure of the Bloomsbury Group. He is best known for his debunking portraits of Cardinal Manning, Florence Nightingale, Dr. Arnold and General Gordon, published together as Eminent Victorians (London: Chatto & Windus, 1918; Russell’s library), which BR read in Brixton with great amusement as well as some critical reservations (see Letter 7). Although Strachey was homosexual, he and the artist Dora Carrington were devoted to each other and from 1917 lived together in Tidmarsh, Berkshire. BR had become acquainted with the somewhat eccentric Strachey, a fellow Cambridge Apostle, while his slightly younger contemporary was reading history at Trinity College. He admired Strachey’s literary gifts, but doubted his intellectual honesty. Almost three decades later BR fleshed out the unflattering thumbnail of Strachey drawn for Ottoline in Letter 7, in a “Portrait from Memory” for BBC radio. Strachey was “indifferent to historical truth”, BR alleged in that broadcast, “and would always touch up the picture to make the lights and shades more glaring and the folly or wickedness of famous people more obvious” (The Listener 48 [17 July 1952]: 98). Main biography: Michael Holroyd, Lytton Strachey: a Critical Biography, 2 vols. (London: Heinemann, 1967–68).

Miles Malleson

Miles Malleson (1888–1969), actor and playwright, was born in Croydon, Surrey, the son of Edmund and Myrrha Malleson. He married his first wife, a fellow actor, Lady Constance Annesley (stage name, Colette O’Niel), in 1915. They had met at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts). Their marriage was an “open” one. In 1914 Miles enlisted in the City of London Fusiliers and was sent to Malta. He became ill and was discharged, unfit for further service. He became active in the No-Conscription Fellowship and wrote anti-war stage plays as well as a pamphlet, Cranks and Commonsense (1916). In the 1930s he began to write for the screen and act in films, in which he became a very well-known character actor, as well as continuing his stage career at the Old Vic in London. He married three times: his second marriage was to Joan Billson, a physician (married 1923, divorced 1940), with whom he had two children; his third wife was Tatiana Lieven, an actress (married 1946). He died in London in March 1969.

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

Philip Jourdain

Philip Edward Bertrand Jourdain (1879–1919), Cambridge-educated logician and historian of mathematics and logic. As a student at Cambridge he took BR’s course on mathematical logic in 1901–02 and subsequently wrote many articles on mathematical logic, set theory, and the foundations of mathematics, among a number of other topics. His extraordinary productivity was achieved despite the ravages of Friedreich’s ataxia, a form of progressive paralysis that killed him in 1919. His extensive correspondence with BR was published (with commentary) in I. Grattan-Guinness, Dear Russell — Dear Jourdain (London: Duckworth, 1977).

Principia Mathematica

Principia Mathematica, the monumental, three-volume work coauthored with Alfred North Whitehead and published in 1910–13, was the culmination of BR’s work on the foundations of mathematics. Conceived around 1901 as a replacement for the projected second volumes of BR’s Principles of Mathematics (1903) and of Whitehead’s Universal Algebra (1898), PM was intended to show how classical mathematics could be derived from purely logical principles. For a large swath of arithmetic this was done by actually producing the derivations. A fourth volume on geometry, to be written by Whitehead alone, was never finished. In 1925–27 BR, on his own, produced a second edition, adding a long introduction, three appendices and a list of definitions to the first volume and corrections to all three. (See B. Linsky, The Evolution of Principia Mathematica [Cambridge U. P., 2011].) In this edition, under the influence of Wittgenstein, he attempted to extensionalize the underlying intensional logic of the first edition.

Viscount Northcliffe

Alfred Charles Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe (1865–1922), press baron, whose stable of newspapers — especially the jingoistic Daily Mail — were militantly Germanophobic. For the last year of the war, Northcliffe promoted British war aims in an official capacity, as Director of Propaganda in Enemy Countries, although this government role did not inhibit his newspapers from challenging the political and military direction of the war effort.

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).