Brixton Letter 66

BR to Ottoline Morrell

August 11, 1918

- ALS

- Texas

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-66Auto. 2: 90

BRACERS 18685

<Brixton Prison>1

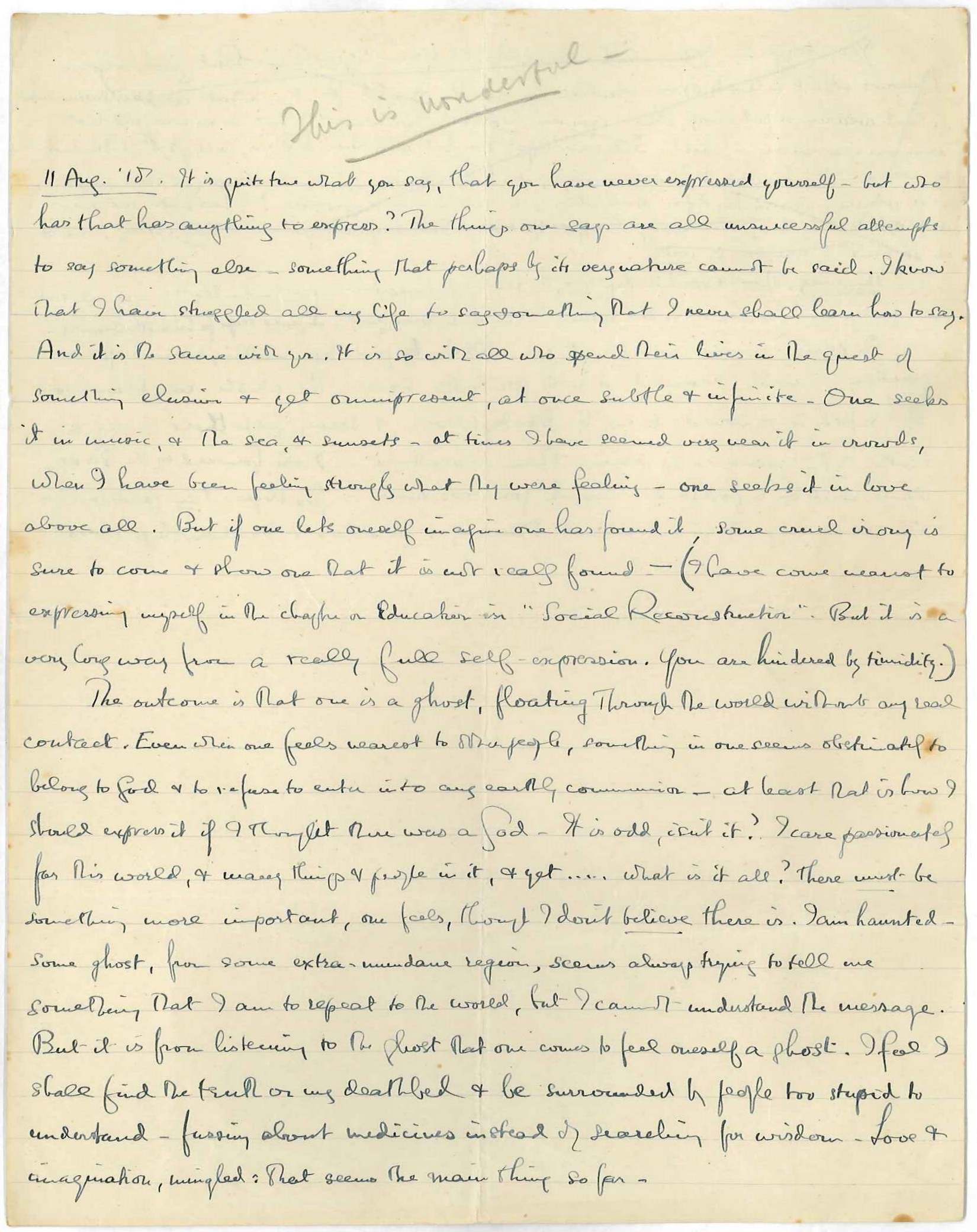

11 Aug. ’18.

It is quite true what you say, that you have never expressed yourself2 — but who has that has anything to express? The things one says are all unsuccessful attempts to say something else — something that perhaps by its very nature cannot be said. I know that I have struggled all my life to say something that I never shall learn how to say. And it is the same with you. It is so with all who spend their lives in the quest of something elusive and yet omnipresent, at once subtle and infinite. One seeks it in music, and the sea, and sunsets — at times I have seemed very near it in crowds,3 when I have been feeling strongly what they were feeling — one seeks it in love above all. But if one lets oneself imagine one has found it, some cruel irony is sure to come and show one that it is not really found. — I have come nearest to expressing myself in the chapter on Education in Social Reconstruction.4 But it is a very long way from a really full self-expression. You are hindered by timidity.a

The outcome is that one is a ghost, floating through the world without any real contact. Even when one feels nearest to other people, something in one seems obstinately to belong to God and to refuse to enter into any earthly communion — at least that is how I should express it if I thought there was a God. It is odd, isn’t it? I care passionately for this world, and many things and people in it, and yet … what is it all? There must be something more important, one feels, though I don’t believe there is. I am haunted — some ghost, from some extra-mundane region, seems always trying to tell me something that I am to repeat to the world, but I cannot understand the message. But it is from listening to the ghost that one comes to feel oneself a ghost.5 I feel I shall find the truth on my deathbed and be surrounded by people too stupid to understand — fussing about medicines instead of searching for wisdom. Love and imagination, mingled: that seems the main thing so far.

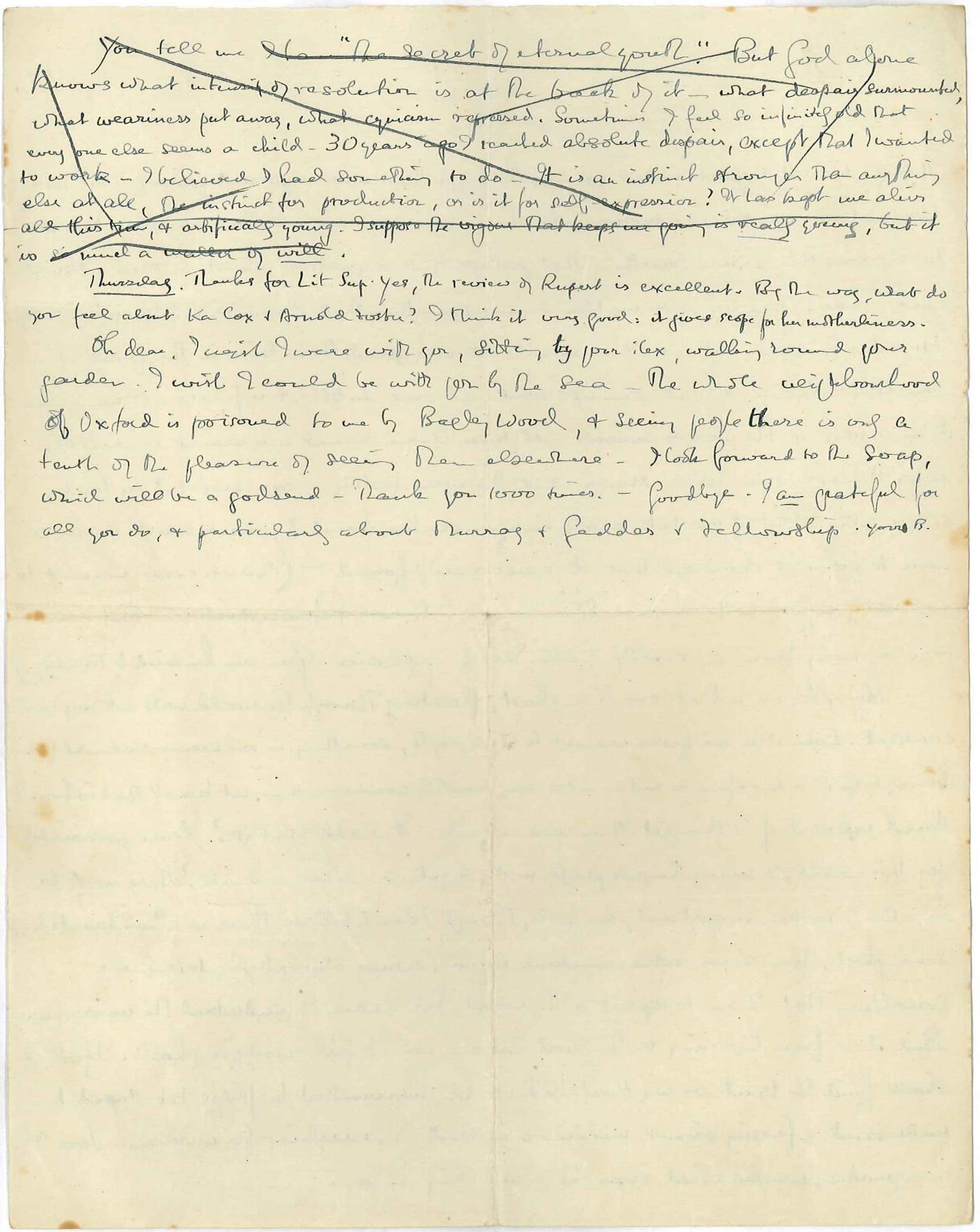

You tell meb I have “the secret of eternal youth”.6 But God alone knows what intensity of resolution is at the back of it — what despair surmounted, what weariness put away, what cynicism repressed. Sometimes I feel so infinitely old that every one else seems a child. 30 years ago I reached absolute despair,7 except that I wanted to work — I believed I had something to do. It is an instinct stronger than anything else at all, the instinct for production, or is it for self-expression? It has kept me alive all this time, and artificially young. I suppose the vigour that keeps me going is really young, but it is so much a matter of will.

Thursday. Thanks for Lit Sup. Yes, the review of Rupert is excellent.8 By the way, what do you feel about Ka Cox and Arnold Foster?9 I think it very good: it gives scope for her motherliness.

Oh dear, I wish I were with you, sitting by your ilex, walking round your garden. I wish I could be with you by the sea. The whole neighbourhood of Oxford is poisoned to me by Bagley Wood,10 and seeing people there is only a tenth of the pleasure of seeing them elsewhere. I look forward to the soap, which will be a godsend. Thank you 1000 times. — Goodbye. I am grateful for all you do, and particularly about Murray and Geddes and Fellowship.

Your

B.

- 1

[document]“This is wonderful —”. (O. Morrell’s note at the top of the sheet.) The letter was edited from a digital scan of the initialled, handwritten original in the Morrell papers at the University of Texas at Austin. The sheet was folded twice. The letter was extracted in BR’s Autobiography, 2: 90.

- 2

what you say ... never expressed yourself “I have never half expressed myself in life — I know and I don’t think I shall ever be able to — but perhaps the memory of one’s spirit will stir something in others that would satisfy one” (Ottoline to BR, 30 July 1918, BRACERS 114752).

- 3

at times I have seemed very near it in crowds BR reflected on this much later: “Throughout my life I have longed to feel that oneness with large bodies of human beings that is experienced by the members of enthusiastic crowds. The longing has often been strong enough to lead me into self-deception” (Auto. 2: 38).

- 4

chapter on Education in Social Reconstruction I.e., in Principles of Social Reconstruction (1916). Continuing to think well of it, BR later chose this chapter for his Selected Papers (New York: Modern Library, 1927).

- 5

ghost … ghost … one comes to feel oneself a ghost By this BR meant the feeling of being “superfluous”, of “looking on but not participating” (as he wrote to Ottoline, BRACERS 18494; Auto. 2: 54). He recalled the feeling when he came to write his Autobiography. Even on Armistice Day — which occurred two months after his release from Brixton — he “felt strangely solitary amid the rejoicings, like a ghost dropped by accident from some other planet” (2: 38). See Letter 75, in which BR described the origin of his sense of being a ghost in response to Ottoline’s reaction to the current letter.

- 6

You tell me I have “the secret of eternal youth” Ottoline had written BR: “So delighted to hear of your New Ideas in Philosophy — ‘The Fountain of Eternal Youth’ ought to be your Name” (July 1918, BRACERS 114750).

- 7

30 years ago I reached absolute despair BR was surely referring to the eighteen months he spent as a student at B.A. Green’s University and Army Tutors, in Southgate, London. He attended this “Army crammer”, as he unflatteringly remembered the institution(Auto. 1: 42), in preparation for the Trinity College scholarship examination, which he sat in December 1889.In a deleted passage in another later writing, “The Importance of Shelley” (1957), BR recalled his reaction to the young men there: “Until I went to Cambridge, most of my contemporaries whom I knew filled me with disgust, so that my love of the human species was tempered by loathing of most of the examples I came across” (Papers 29: 586–7). Gradually, he said, he “got used to their conversation and ceased to be shocked by it. I remained profoundly unhappy.… I did not, however, commit suicide, because I wished to know more of mathematics” (Auto. 1: 43). Much later, in 1959, BR was asked, “What was your worst period of unhappiness?” He replied: “Well I was very, very unhappy in adolescence. I think many adolescents are. I had no friends, nobody I could talk to. I thought that I was contemplating suicide all the time and was restraining with difficulty from this act and this was not really true” (Bertrand Russell Speaks His Mind (Cleveland and New York: World, 1960), p. 71. Compare the cognate topic in Letter 95 (also to Ottoline), note 18 on “the worst time of my life”.

- 8

Lit. Sup. … review of Rupert is excellent The (anonymous) review of The Collected Poems of Rupert Brooke; with a Memoir, edited by Edward Marsh (London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1918), was by Virginia Woolf: “Rupert Brooke”, The Times Literary Supplement, 8 Aug. 1918, p. 371. Like BR, Woolf had known Brooke and wrote appreciatively of him as a person. Marsh’s lengthy memoir of the poet concluded with a tribute to him from Winston Churchill (previously published in The Times), which BR — appalled as he was by the loss of men such as Brooke in a futile war — must have regarded as especially loathsome: “Joyous, fearless, versatile, deeply instructed, with classic symmetry of mind and body, he was all that one would wish England’s noblest sons to be in days when no sacrifice but the most precious is acceptable, and the most precious is that which is most freely proffered” (Collected Poems, p. clix).

- 9

what do … Ka Cox and Arnold Foster? Before the war, as a student at Cambridge, Katherine (“Ka”) Laird Cox (1887–1938) had been one of the group of “Neo-Pagans” around Rupert Brooke — with whom she fell in love. In September 1918 she married William Arnold-Forster (1885–1951), a painter and a member of the Royal Naval Reserve. Ottoline agreed with BR’s assessment of the match (17 Aug. 1918, BRACERS 14755).

- 10

Bagley Wood BR lived at Bagley Wood, Oxford, from 1905 to 1910 with his first wife, Alys. See S. Turcon, “Bagley Wood”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 149 (Spring 2014): 19–22. His marriage was by that time a sham. He wrote in his Autobiography: “The strain of unhappiness combined with very severe intellectual work [on Principia Mathematica] … was very great” (1: 152).

Textual Notes

- a

I have come … timidity. These sentences are in parentheses, and appear to have been added later for Ottoline’s typed selection of BR’s letters to her. The parentheses are retained in his Autobiography.

- b

You tell me This paragraph has eight lines drawn through it at different angles. It is not BR’s style of deletion; the paragraph is therefore retained.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Fellowship Plan

Since the upper-age limit for compulsory military service had been increased to 50 in April 1918, BR was faced with the unnerving prospect of being conscripted after his release from Brixton. Early in his imprisonment he was already wondering about his “position when I emerge from here” (Letter 9). While his conviction was still under appeal, he had broached with Clifford Allen and Gilbert Murray the possibility of avoiding military service, not by asserting his conscientious objection to it, but by obtaining accreditation of his philosophical research as work of national importance (see note to Letter 24). The Pelham Committee, set up by the Board of Trade in March 1916, was responsible for the designation of essential occupations and recommending to the local tribunals, who adjudicated claims for exemption from military service, that C.O.s be considered for such positions. BR reasoned to Murray on 2 April that a dispensation to practise philosophy (as opposed to working outside his profession), would enable to him to “avoid prison without compromise” — i.e., of his political and moral opposition to conscription (BRACERS 52367). Although BR intended to withdraw from political work, he told Murray two days later, he would not promise to abstain from peace campaigning (BRACERS 52369). It should be noted that C.O.s who accepted alternative service in special Home Office camps were expressly prohibited from engaging in pacifist activities (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 231).

BR was far from sanguine about the prospect of success before a local tribunal. But he came to think (by early June) that his chances would be improved if his academic supporters interceded directly with the Minister of National Service, Sir Auckland Geddes. In addition, he calculated that such entreaties would be more effective if those acting on his behalf could secure and even endow a fellowship for him and thereby have “something definite to put before Geddes” (Letter 12; see also Letters 15 and 19). BR definitely wanted to rededicate himself to philosophy and would have welcomed a new source of income from academic employment (see Letter 22). But the “financial aspect was quite secondary”, he reminded Frank on 24 June (Letter 27); he was interested in the fellowship plan primarily as a safeguard against being called up, for teachers over 45 were not subject to the provisions of the recently amended Military Service Act. In the same letter, however, BR told his brother that “I wish it <the plan> dropped” on account of reservations expressed to him in person by Wildon Carr and A.N. Whitehead (see also Letter 31), two philosophers whom he respected but who seemed to doubt whether BR’s financial needs were as great as they appeared (see note to Letter 102).

Yet BR’s retreat was only temporary. On 8 August, he expressed to Ottoline a renewed interest in the initiative, and a few days later, she, her husband and Gladys Rinder met in London to discuss the matter. As Ottoline reported to BR, “we all felt that it was useless to wait for others to start and we decided that P. and I should go and see Gilbert M. and try and get him to work it with the Philosophers” (11 Aug. 1918, BRACERS 114754). BR probably wanted Murray to spearhead this lobbying (see also Letters 65 and 70) because of his political respectability and prior success in persuading professional philosophers to back an appeal to the Home Secretary for BR’s sentence to be served in the first division (see Letter 6). Murray did play a leading role but not until early the following month, when BR was anxious for the fellowship plan to succeed as his release date neared. The scheme finally gathered momentum after a meeting between Ottoline, Rinder and Carr on 6 September 1918, at which the philosopher and educationist T. Percy Nunn, another academic supporter of BR, was also present. Within a few days Murray had drafted a statement with an appeal for funds, which was endorsed by Carr, Whitehead, Nunn, Samuel Alexander, Bernard Bosanquet, G. Dawes Hicks, A.E. Taylor and James Ward. This memorial was then circulated in confidence to philosophers and others, but only after BR’s release from Brixton. (Financial pledges had already been made by a few of BR’s friends and admirers, notably Lucy Silcox and Siegfried Sassoon.) BR’s solicitor, J.J. Withers, became treasurer of this endowment fund, the goal of which was to provide BR with £150 or £200 per annum over three years. On 30 August BR had confessed to Ottoline that he did not want an academic position “very far from London” (Letter 89) and reiterated this desire in a message to Murray communicated by Rinder (Letter 97). On 6 September Rinder (BRACERS 79633) hinted that she already knew where the appointment would be, but there are no other indications that a particular establishment had been decided upon. Ultimately, no affiliation was contemplated for BR, so the memorial stated, because “in the present state of public feeling no ordinary university institution is likely to be willing to employ him as a teacher” (copy in BRACERS 56750). The circular talked instead of a “special Lectureship”, and the £100 BR received from the fund early in 1919 was explicitly issued as payment for lectures (on “The Analysis of Mind”; see syllabus, in Papers 9: App. III.1) that he would deliver that spring. BR’s solicitor also informed him that provision existed to pay him a further £100 for an autumn lecture course (see syllabus, ibid.: App. III.2), and Withers anticipated that these arrangements might “last two or three years” (2 Jan. 1919, BRACERS 81764). BR had already obtained a £50 gift from the fund in November 1918. Somewhat ironically, the critical importance of a teaching component to the fellowship plan — as insurance against conscription — was reduced by the authorities hesitating to hound BR any further after his imprisonment, and all but nullified by the end of the war a few weeks later. (There were no fresh call-ups, but the last of the C.O.s already in prison were not released until August 1919, and conscription remained in effect until April 1920.)

Gilbert Murray

Gilbert Murray (1866–1957), distinguished classical scholar and dedicated liberal internationalist. He was Regius Professor of Greek at Oxford, 1908–36, and chair of the League of Nations Union, 1923–36. He and BR enjoyed a long and close friendship that was ruptured temporarily by bitter disagreement over the First World War. After Murray published The Foreign Policy of Sir Edward Grey, 1906–1915, in defence of Britain’s pre-war diplomacy, BR responded with a detailed critique, The Policy of the Entente, 1904–1914: a Reply to Professor Gilbert Murray (37 in Papers 13). Yet Murray still took the lead in campaigning to get BR’s sentence reassigned from the second to the first division and (later) in leading an appeal for professional and financial backing of an academic appointment for BR upon his release (the “fellowship plan”, which looms large in his prison correspondence). BR was still thankful for Murray’s exertions some 40 years later. See his portrait of Murray, “A Fifty-Six Year Friendship”, in Murray, An Unfinished Autobiography with Contributions by His Friends, ed. Jean Smith and Arnold Toynbee (London: Allen & Unwin, 1960).

Rupert Brooke

Rupert Chawner Brooke (1887–1915), poet and soldier, became a tragic symbol of a generation doomed by war after he died from sepsis en route to the Gallipoli theatre. Although BR had previously expressed a dislike, even loathing, of Brooke in letters to Ottoline, he too placed him in this tragic posthumous light. Rupert “haunts one always”, he wrote Ottoline shortly after the poet’s death in April 1915, and (five months later) “one is made so terribly aware of the waste when one is here [Trinity College]…. Rupert Brooke’s death brought it home to me” (BRACERS 18431, 18435: see also Letter 85). Brooke had become acquainted with BR and members of the Bloomsbury Group in pre-war Cambridge. BR was an examiner of Brooke’s King’s College fellowship dissertation (later published as John Webster and the Elizabethan Drama [1916]), with which he was pleasantly and surprisingly impressed. “It is astonishingly well-written, vigorous, fertile, full of life”, he reported to Ottoline in February 1912 (BRACERS 17447). After the outbreak of war Brooke obtained a commission in a naval reserve unit attached to a military combat battalion; his war poetry captures the patriotic idealism that compelled so many young men to enlist.

Sir Auckland Geddes

Sir Auckland Geddes (1879–1954; 1st Baron Geddes, 1942) was returned unopposed as Conservative M.P. for Basingstoke in a by-election held in October 1917. Before this entry into civilian public life, he held the rank of Brigadier-General as director of recruiting at the War Office. He was an ardent champion of conscription even in peacetime and had a long-standing interest in the military, which he expressed before the war as a volunteer medical officer in the British Army Reserve. He had studied medicine and was Professor of Anatomy at McGill University, Montreal, when the outbreak of war prompted an immediate return to Britain in order to enlist. After a riding accident rendered Geddes unfit for front-line duties, he became a staff officer in France with a remit covering the supply and deployment of troops. He performed similar duties at the War Office until his appointment in August 1917 as a Minister of National Service with broad powers over both military recruitment and civilian labour. Geddes held two more Cabinet positions in Lloyd George’s post-war Coalition Government before his appointment in 1920 as British Ambassador to the United States. After returning from Washington on health grounds three years later, Geddes embarked upon a successful business career, becoming chairman in 1925 of the Rio Tinto mining company. See Oxford DNB.

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.