Brixton Letter 60

BR to Gladys Rinder

August 5, 1918

- TL(TC,CAR)

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-60

BRACERS 116691

<Brixton Prison>1

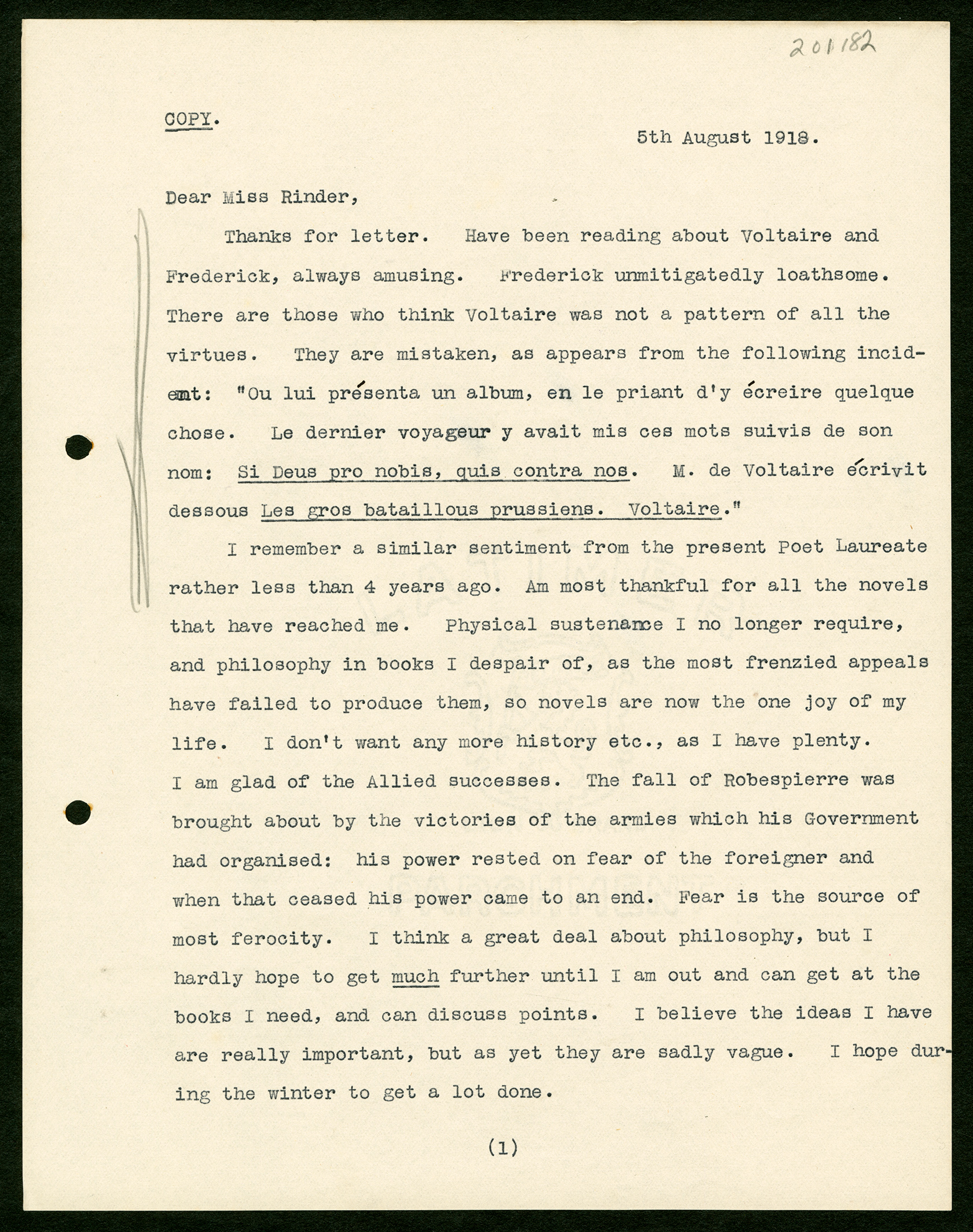

5th August 1918

Dear Miss Rinder,

Thanks for letter.2 Have been reading about Voltaire and Frederick,3 always amusing. Frederick unmitigatedly loathsome. There are those who think Voltaire was not a pattern of all the virtues. They are mistaken, as appears from the following incident: “On lui présenta un album, en le priant d’y écrire quelque chose. Le dernier voyageur y avait mis ces mots suivis de son nom: Si Deus pro nobis, quis contra nos? M. de Voltaire écrivit au-dessous Les gros bataillons prussiens. Voltaire.”4, a

I remember a similar sentiment from the present poet Laureate rather less than 4 years ago.5 Am most thankful for all the novels that have reached me. Physical sustenance I no longer require, and philosophy books I despair of, as the most frenzied appeals have failed to produce them, so novels are now the one joy of my life. I don’t want any more history etc., as I have plenty. I am glad of the Allied successes.6 The fall of Robespierre was brought about by the victories of the armies7 which his Government had organised: his power rested on fear of the foreigner and when that ceased his power came to an end. Fear is the source of most ferocity. I think a great deal about philosophy, but I hardly hope to get much further until I am out and can get at the books I need, and can discuss points. I believe the ideas I have are really important, but as yet they are sadly vague. I hope during the winter to get a lot done.

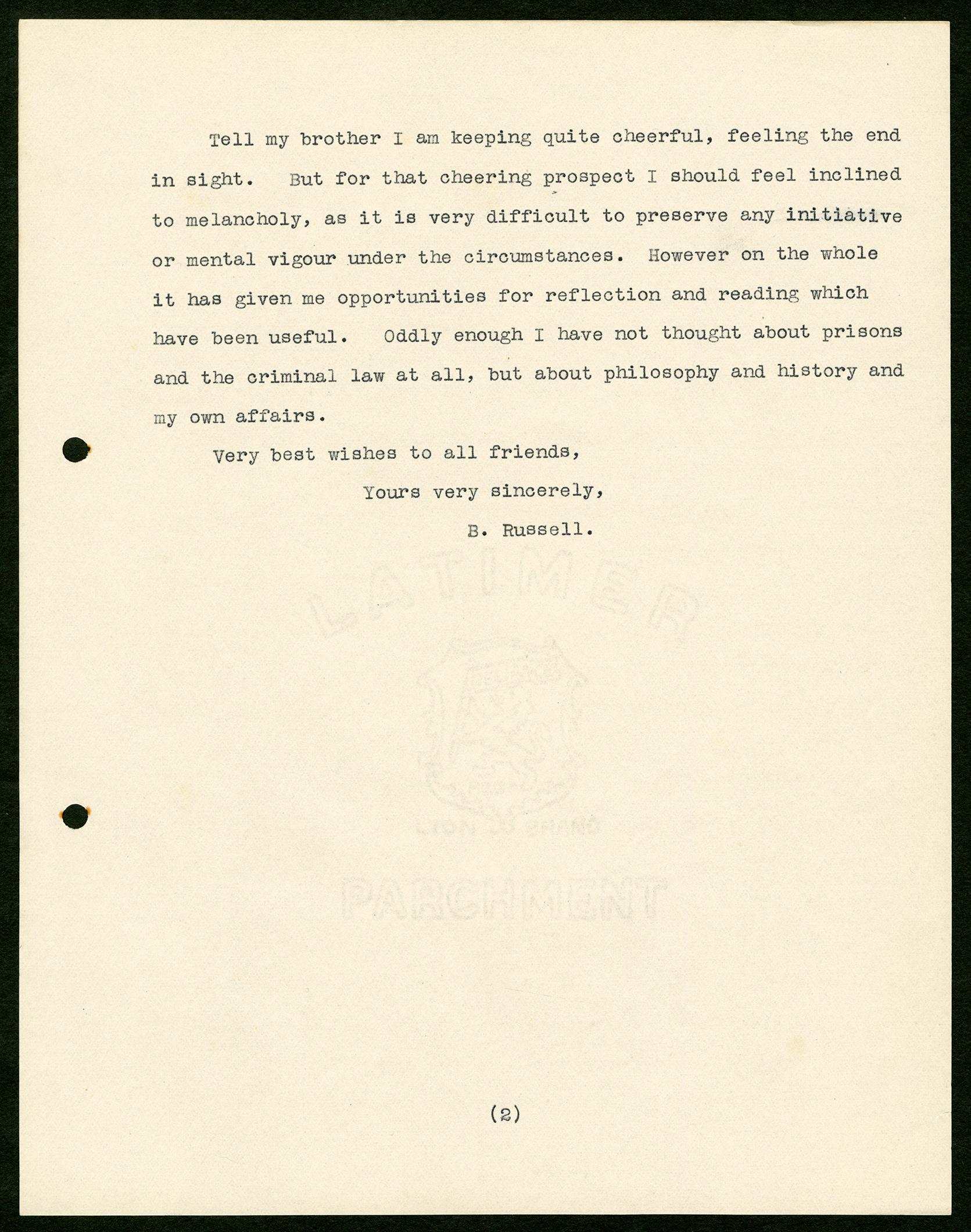

Tell my brother I am keeping quite cheerful, feeling the end in sight. But for that cheering prospect I should feel inclined to melancholy, as it is very difficult to preserve any initiative or mental vigour under the circumstances. However on the whole it has given me opportunities for reflection and reading which have been useful. Oddly enough I have not thought about prisons and the criminal law at all,8 but about philosophy and history and my own affairs.

Very best wishes to all friends,

Yours very sincerely

B. Russell.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from a typed carbon copy (document RA1 710.054845), which has corrections in Rinder’s hand. A second typed copy (document 201182) is in the Malleson papers, also in the Russell Archives, and is judged to be later as it appears to be a retyping of document .054845 or its ribbon copy.

- 2

Thanks for letter. The letter is unidentified.

- 3

Have been reading about Voltaire and Frederick Frederick II (called “the Great”, 1712–1786, ruled from 1740) was a prototypical enlightened despot, impatient with ancien régime conventions and influenced by the outlook of the French philosophes. Indeed, he corresponded with Voltaire before persuading him in 1750 to visit the royal estate in Potsdam. But relations between Prussian monarch and French thinker were strained, and Voltaire broke from Frederick three years later.

- 4

“On lui présenta … Voltaire.” [Translation:] “He was presented with an album, asking him to write something in it. The last traveller had put down these words followed by his name: If God be for us, who can be against us? M. de Voltaire wrote below: The big Prussian battalions. Voltaire.” See also textual note a.

- 5

similar sentiment … present poet Laureate … less than 4 years ago A few days after the outbreak of war, The Times (8 Aug. 1914, p. 7) published a jingoistic call to arms by Robert Bridges, poet laureate since his appointment the previous year by King George V. This short poem, entitled “Wake Up, England”, opened as follows: “Thou careless, awake! / Thou peacemakers, fight! / Stand, England, for honour, / And God guard the Right!”

- 6

Allied successes Early Allied gains in the second Battle of the Marne (see note 21 to Letter 44) had turned into a major strategic victory. Although this forward movement stalled on 6 August 1918, only two days later a new attack (the Battle of Amiens) was successfully launched from a different sector of the Western Front. The action was the first in a series of Allied assaults that rapidly pushed the German Army into retreat across the entire front and resulted, barely 100 days later, in the signing of the Armistice.

- 7

fall of Robespierre ... victories of the armies When the radical Jacobin Maximilien Robespierre (1758–1794) ultimately fell victim to the reign of terror he had helped unleash the previous year, French revolutionary armies had just achieved significant victories in the Battles of Tourcoing in northern France and of Fleurus in Flanders (18 May and 26 June 1794, respectively). The French then succeeded in pushing Coalition forces across the Rhine and in occupying Belgium, southern Holland and parts of the Rhineland.

- 8

prisons and the criminal law at all BR had a chapter, “Government and the Law”, in Roads to Freedom (1918), in which he described what he knew of prison conditions before he went in (p. 135), and then a footnote in the second printing (1919) reporting on his experience: “This was written before the author had any personal experience of the prison system. He personally met with nothing but kindness at the hands of the prison officials” (ibid.). He was on the Prison System Enquiry Committee, formed in early 1919 and three years later delivering its report, English Prisons Today by Stephen Hobhouse and A. Fenner Brockway (London: Longmans, Green). Six years later BR read and reviewed Prisons and Common Sense (London: J.B. Lippincott, 1924) by American penal reformer Thomas Mott Osborne (The New Leader, London, 9, no. 7 [14 Nov. 1924]: 3, 4), and in 1931 he wrote a Hearst column entitled “Are Criminals Worse than Other People?” (reprinted in Mortals and Others [London: Routledge, 2009], pp. 32–4). In the 1950s BR joined campaigns in opposition to capital punishment and the legal proscription of homosexuality.

Textual Notes

- a

“On lui présenta … Voltaire.” The French text in Rinder’s typed transcription of BR’ letter is here corrected from “Ou lui présenta un album, eu le priant d’y écreire quelque chose. Le dernier voyageur y avait mis ces mots suivis de son nom: Si Deus pro nobis, quis contra nos. M. de Voltaire écririt dessous Les gros bataillons prussiens. Voltaire.” See Sébastian G. Longchamp and Jean-Louis Wagnière, Mémoires sur Voltaire: et sur ses ouvrages (Paris: André, 1826), 1: 35. See note 4 above for the translated quotation.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).