Brixton Letter 59

BR to Constance Malleson

August 4, 1918

- AL

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-59

BRACERS 19340

<Brixton Prison>1

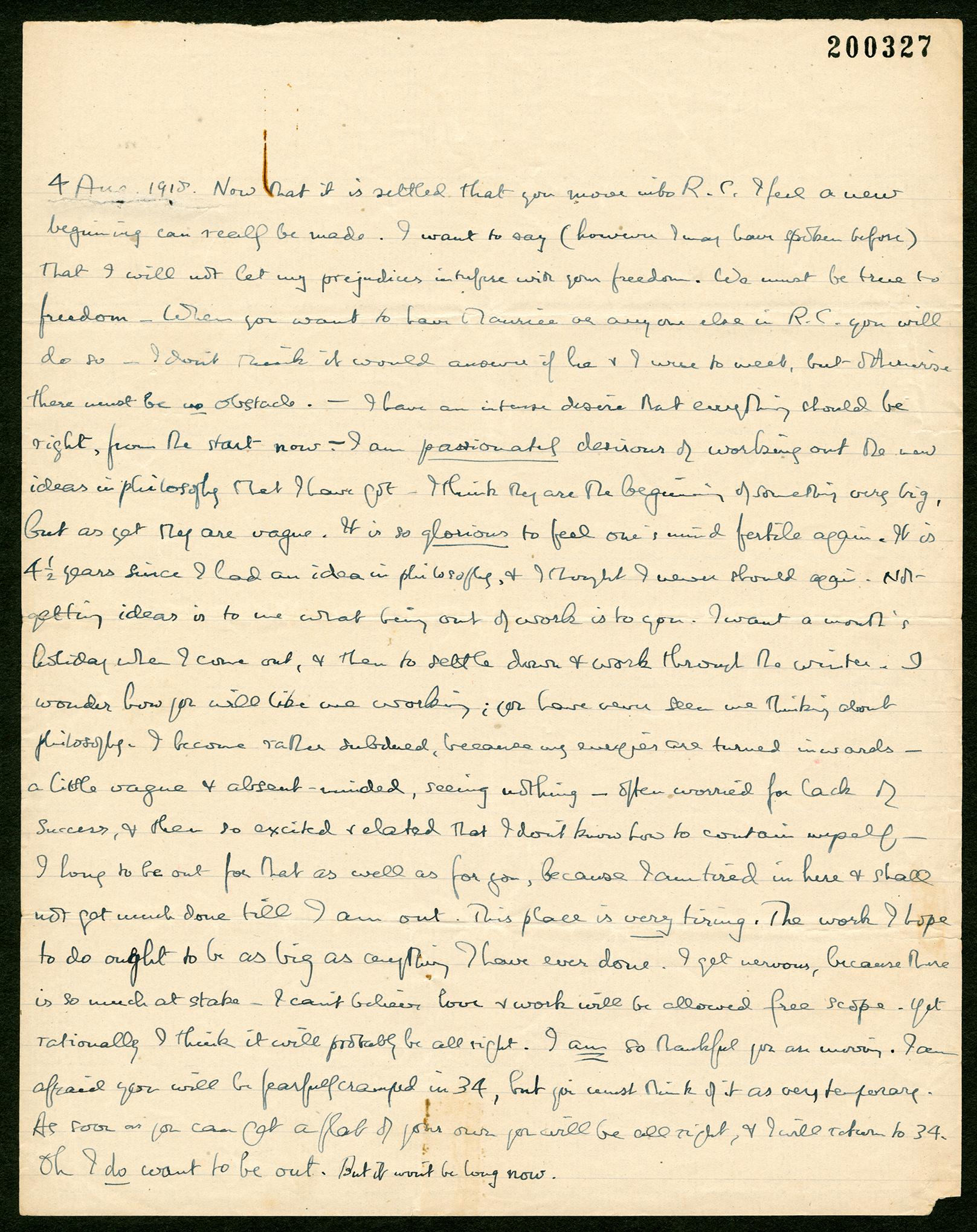

4 Aug. 1918.

Now that it is settled that you move into R.C. I feel a new beginning can really be made. I want to say (however I may have spoken before) that I will not let my prejudices interfere with your freedom. We must be true to freedom. When you want to have Maurice or any one else in R.C. you will do so. I don’t think it would answer if he and I were to meet, but otherwise there must be no obstacle. — I have an intense desire that everything should be right, from the start now. — I am passionately desirous of working out the new ideas in philosophy that I have got. I think they are the beginning of something very big, but as yet they are vague. It is so glorious to feel one’s mind fertile again. It is 4½ years since I had an idea2 in philosophy, and I thought I never should again. Not getting ideas is to me what being out of work is to you. I want a month’s holiday when I come out, and then to settle down and work through the winter. I wonder how you will like me working; you have never seen me thinking about philosophy. I become rather subdued, because my energies are turned inwards — a little vague and absent-minded, seeing nothing — often worried for lack of success, and then so excited and elated that I don’t know how to contain myself. I long to be out for that as well as for you, because I am tired in here and shall not get much done till I am out. This place is very tiring. The work I hope to do ought to be as big as anything I have ever done.3 I get nervous, because there is so much at stake — I can’t believe love and work will be allowed free scope. Yet rationally I think it will probably be all right. I am so thankful you are moving. I am afraid you will be fearfully cramped in 34,4 but you must think of it as very temporary. As soon as you can get a flat of your own you will be all right, and I will return to 34. Oh I do want to be out. But it won’t be long now.a

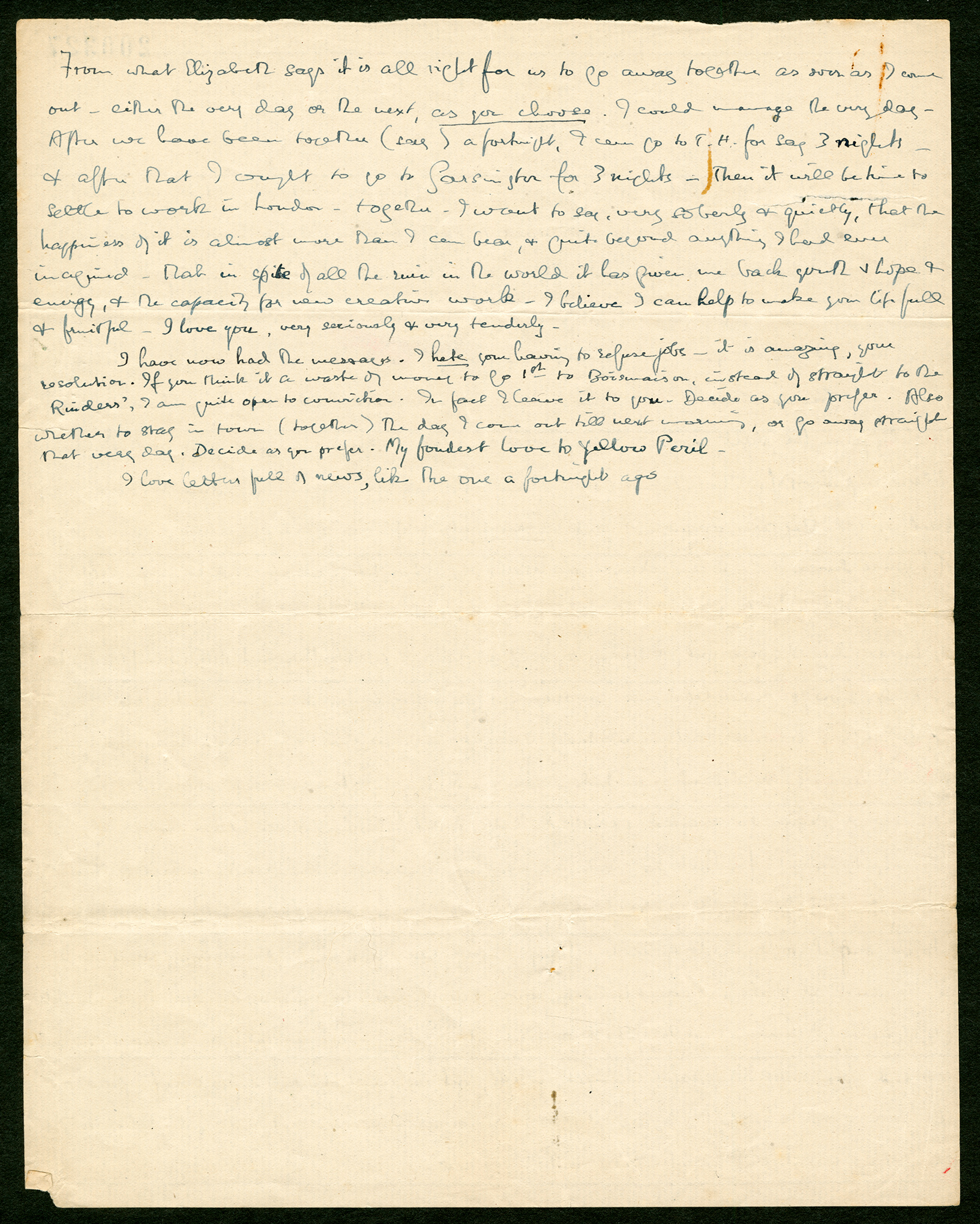

From what Elizabeth says it is all right for us to go away together as soon as I come out — either the very day or the next, as you choose. I could manage the very day. After we have been together (say) a fortnight, I can go to T.H. for say 3 nights — and after that I ought to go to Garsington for 3 nights. Then it will be time to settle to work in London — together. I want to say, very soberly and quietly, that the happiness of it is almost more than I can bear, and quite beyond anything I had ever imagined — that in spite of all the ruin in the world it has given me back youth and hope and energy, and the capacity for new creative work. I believe I can help to make your life full and fruitful. I love you, very seriously and very tenderly.

I have now had the messages. I hate your having to refuse jobs5 — it is amazing, your resolution. If you think it a waste of money to go 1st to Boismaison, instead of straight to the Rinders’,6 I am quite open to conviction. In fact I leave it to you. Decide as you prefer. Also whether to stay in town (together) the day I come out till next morning, or go away straight that very day. Decide as you prefer. My fondest love to Yellow Peril.7

I love letters full of news, like the one a fortnight ago.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from an unsigned sheet in BR’s handwriting in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. The sheet was folded twice so that the bottom half of the verso, which was left blank, formed a privacy cover consisting of two quarter-sheets.

- 2

4½ years since I had an idea BR was surely referring to his idea of a perspectival space of six dimensions, first published in “The Relation of Sense-Data to Physics” (Scientia 16 [July 1914]: 1–27; reprinted in Mysticism and Logic [1918]; 1 in Papers 8) and then in Our Knowledge of the External World, Lecture 3 (1914).

- 3

The work I hope to do ought to be as big as anything I have ever done. BR’s plans for what he was already calling “The Analysis of Mind” were certainly ambitious, as is revealed by the only surviving outline of them, “Bertrand Russell’s Notes on the New Work Which He Intends to Undertake” (Papers 8: App. II), which covered only the “section dealing with cognition” . But when he says the work will be “as big as anything I have ever done”, he must mean anything that he has done on his own, for it is hardly possible that he expected the work would be as big as Principia Mathematica. Even so, the work which eventually resulted, primarily a long paper “On Propositions: What They Are and How They Mean” (1919) and the book The Analysis of Mind (1921), even when taken together, fell far short in scale of The Principles of Mathematics (1903), the largest work he had done on his own by this time.

- 4

34 BR’s flat, 34 Russell Chambers, Bury Street (since renamed Bury Place), London WC1. It is unclear why BR thought she would be cramped there — her current flat, The Attic, appears to have been about the same size.

- 5

had the messages. I hateyou having to refuse jobs This presumably concerned Colette’s refusal to act in a film about Lloyd George (see also note 6 to Letter 64). Maurice Elvey directed The Life Story of David Lloyd George, a film completed in 1918 but never exhibited — possibly because of its subject’s withdrawal of support from the project (see Sarah Barrow and John White, eds., Fifty Key British Films [London and New York: Routledge, 2008], p. 8). It was “an intelligent little man”, probably Harry or Simon Rowson, who headed the Ideal Film Company, who approached Colette about the Lloyd George film (BRACERS 113147). See also Letter 87, note 12.

- 6

the Rinders’Miss Rinder offered her family’s cottage as a place to stay once BR left prison. Windmill Cottage was in Icklesham, near Winchelsea. Although not on the coast, it was not far away.

- 7

Yellow PerilColette’s dressing gown.

Textual Notes

- a

But it won’t be long now. Because of the difference in handwriting, this sentence must have been an after-thought.

Boismaison

Colette and BR vacationed at a house, The Avenue, owned by Mrs. Agnes Woodhouse and her husband, in the countryside near Ashford Carbonel, Shropshire, in August 1917. They nicknamed the house “Boismaison”. Agnes Woodhouse took in paying guests. Their first visit was idyllic. They returned for other vacations — in 1918 before he entered prison and in April 1919. Their plan to go soon after he got out of prison failed because their relationship faltered for a time. They discussed returning in the summer of 1919 — a booking was even made for 12–19 July — but in the end they didn’t go. See S. Turcon, “Then and Now: Bertie and Colette’s Escapes to the Peak District and Welsh Borderlands”, Russell 34 (2014): 117–30.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

David Lloyd George

Through ruthless political intrigue, David Lloyd George (1863–1945) emerged in December 1916 as the Liberal Prime Minister of a new and Conservative-dominated wartime Coalition Government. The “Welsh wizard” remained in that office for the first four years of the peace after a resounding triumph in the notorious “Coupon” general election of December 1918. BR despised the war leadership of Lloyd George as a betrayal of his Radical past as a “pro-Boer” critic of Britain’s South African War and as a champion of New Liberal social and fiscal reforms enacted before August 1914. BR was especially appalled by the Prime Minister’s stubborn insistence that the war be fought to a “knock-out” and by his punitive treatment of imprisoned C.O.s. For the latter policy, as BR angrily chastised Lloyd George at their only wartime meeting, “his name would go down to history with infamy” (Auto. 2: 24).

Elizabeth Russell

Elizabeth Russell, born Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941), was a novelist who in 1891 married Graf von Arnim-Schlagenthin. She became known as “Elizabeth”, the name she used in publishing Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898), and she remained widely known as Elizabeth von Arnim, although the Library of Congress catalogues her as Mary Annette (Beauchamp), Countess von Arnim. She was a widow when she married BR’s brother, Frank, on 11 February 1916. The marriage was quickly in difficulty; she left it for good in March 1919, but they were never divorced and she remained Countess Russell (becoming Dowager Countess after Frank’s death in 1931).

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Maurice Elvey

Maurice Elvey (1887–1967) was a prolific film director (of silent pictures especially) and enjoyed a very successful career in that industry lasting many decades. Born William Seward Folkard into a working-class family, Elvey changed his name around 1910, when he was acting. He directed his first film, The Fallen Idol, in 1913. By 1917, when he directed Colette in Hindle Wakes, he had married for a second time — to a sculptor, Florence Hill Clarke — his first marriage having ended in divorce. Elvey and Colette had an affair during the filming of Hindle Wakes, beginning in September 1917, which caused BR great anguish. In addition to his feeling of jealousy during his imprisonment, BR was worried over the rumour that Elvey was carrying a dangerous sexually transmitted disease. (See BR, “My First Fifty Years”, RA1 210.007050–fos. 127b, 128, and Monk, 2: 507). Colette later maintained that Elvey cleared himself (“Letters to Bertrand Russell from Constance Malleson, 1916–1969”, p. 154, typescript, RA). BR removed the allegation from the Autobiography as published (see 2: 37), but he remained fearful. After Elvey’s long-lost wartime film about the life of Lloyd George was rediscovered and restored in the 1990s, it premiered to considerable acclaim (see Letter 87, note 12).

Russell Chambers

34 Russell Chambers, Bury Street (since renamed Bury Place), London WC1, BR’s flat since 1911. Helen Dudley rented the flat in late 1916 or early 1917. In May 1918 she sublet it to Clare Annesley. Colette moved in on 9 September 1918 and stayed until June 1919. BR did not give up the lease until December 1923. See S. Turcon, “Russell Chambers, Other London Flats, and Country Homes, 1911–1923”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 150 (Fall 2014): 30–4. “Russell Chambers, Other London Flats, and Country Homes, 1911–1923”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 150 (Fall 2014): 30–4.

Telegraph House

Telegraph House, the country home of BR’s brother, Frank. It is located on the South Downs near Petersfield, Hants., and North Marden, W. Sussex. See S. Turcon, “Telegraph House”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 154 (Fall 2016): 45–69.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.