Brixton Letter 46

BR to Constance Malleson

July 24, 1918

- TL(TC)

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-46

BRACERS 131599

<Brixton Prison>1, 2

Yes, it makes one very lonely having the sort of power you wrote of.3 I seek out those few women who are not subservient — quite instinctively. Those whom one dominates cease to count; and yet one can’t help trying to dominate — it is a queer contradiction.

I am glad to know all about Maurice. You must fix your mind on parting from Miles (from living in the same house I mean) at latest when I come out — for his sake as well as yours, and of course for mine — for mine it is absolutely vital. When Miles is wearing you out you are lifeless and the essential quality of you is dead. I may not be at large very long — there is no certainty of escaping prison as a C.O.4 I shouldn’t urge all these things if I were not absolutely sure that both for you and Miles parting is <word missing>.a What makes prison trying is simply the longing for you. But for that I could settle down and vegetate. But I want you, quite terribly. And when I feel things are not prospering with you it grows much harder — I have such a fearful longing to be able to come out and comfort you. <page torn away here>b O my Heart’s Comrade, I feel so near you, so intimate.

Business Let the Attic if you can — we could never be happy there.5

- 1

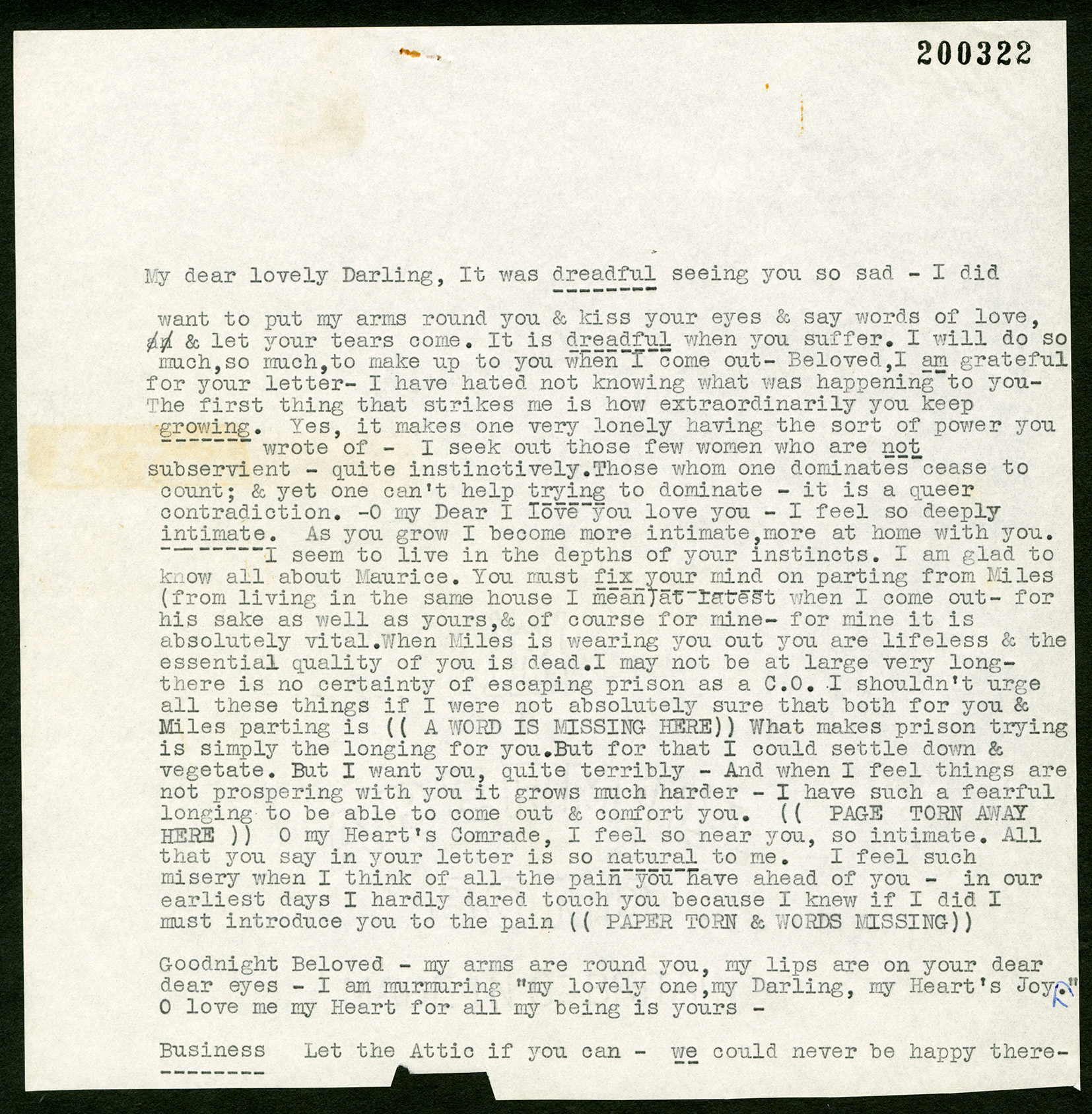

[document] This letter was edited from an unsigned, undated typescript (document 200322) in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. Colette noted on an accompanying slip that the original was missing. In fact, the typescript appears to be a composite of extracts from at least two letters whose originals are not extant in the Russell Archives. An earlier typescript of much of document 200322 is 201122 (of which there is a second, later typescript, RA1 710.052420). 201122 is the source of Letter 47. The portions of 200322 that do not appear in 201122 form the present letter.

- 2

[date] A typed note, presumably by Colette, that came to McMaster with the letter indicates that although the original letter is missing, it was written on a “‘Wed. evg.’, probably on or abt 24 July 1918.”

- 3

you wrote ofColette’s letter was not identified.

- 4

no certainty of escaping prison as a C.O. BR was concerned that since the military service age had been raised to 50 and that even though he would register as a conscientious objector, he might be either kept in prison once he had served his six-month sentence, or sent back almost immediately on his release.

- 5

Let the Attic if you can — we could never be happy there. It is not clear why BR felt that way. Miles had lived in the Attic with Colette, so BR may have wanted to make a fresh start elsewhere with her.

Textual Notes

- a

<a word is …> This remark was added by Colette in full caps when she made the transcription. A typed note indicates that the original is missing and “the following extracts are all that remain of it.”

- b

<page torn away here> This remark was added by Colette in full caps when she made the transcription. A typed note indicates that the original is missing and “the following extracts are all that remain of it.”

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Heart’s Comrade

Colette first called BR her “heart’s comrade” in her letter of 17 November 1916 (BRACERS 112964). On 9 December (BRACERS 112977), she explained: “I want you as comrade as well as lover.” On 9 April 1917 (BRACERS 19145), he reciprocated the sentiment for the first time. In a letter of 1 January 1918 (BRACERS 19260), BR was so upset with her that he could no longer call her “heart’s comrade”. After their relationship was patched up, he wrote on 16 February 1918 (BRACERS 19290): “I do really feel you now again my Heart’s Comrade.” The last time that BR expressed the sentiment in a letter to her was 26 August 1921 (BRACERS 19742).

Maurice Elvey

Maurice Elvey (1887–1967) was a prolific film director (of silent pictures especially) and enjoyed a very successful career in that industry lasting many decades. Born William Seward Folkard into a working-class family, Elvey changed his name around 1910, when he was acting. He directed his first film, The Fallen Idol, in 1913. By 1917, when he directed Colette in Hindle Wakes, he had married for a second time — to a sculptor, Florence Hill Clarke — his first marriage having ended in divorce. Elvey and Colette had an affair during the filming of Hindle Wakes, beginning in September 1917, which caused BR great anguish. In addition to his feeling of jealousy during his imprisonment, BR was worried over the rumour that Elvey was carrying a dangerous sexually transmitted disease. (See BR, “My First Fifty Years”, RA1 210.007050–fos. 127b, 128, and Monk, 2: 507). Colette later maintained that Elvey cleared himself (“Letters to Bertrand Russell from Constance Malleson, 1916–1969”, p. 154, typescript, RA). BR removed the allegation from the Autobiography as published (see 2: 37), but he remained fearful. After Elvey’s long-lost wartime film about the life of Lloyd George was rediscovered and restored in the 1990s, it premiered to considerable acclaim (see Letter 87, note 12).

Miles Malleson

Miles Malleson (1888–1969), actor and playwright, was born in Croydon, Surrey, the son of Edmund and Myrrha Malleson. He married his first wife, a fellow actor, Lady Constance Annesley (stage name, Colette O’Niel), in 1915. They had met at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts). Their marriage was an “open” one. In 1914 Miles enlisted in the City of London Fusiliers and was sent to Malta. He became ill and was discharged, unfit for further service. He became active in the No-Conscription Fellowship and wrote anti-war stage plays as well as a pamphlet, Cranks and Commonsense (1916). In the 1930s he began to write for the screen and act in films, in which he became a very well-known character actor, as well as continuing his stage career at the Old Vic in London. He married three times: his second marriage was to Joan Billson, a physician (married 1923, divorced 1940), with whom he had two children; his third wife was Tatiana Lieven, an actress (married 1946). He died in London in March 1969.

Russell Chambers

34 Russell Chambers, Bury Street (since renamed Bury Place), London WC1, BR’s flat since 1911. Helen Dudley rented the flat in late 1916 or early 1917. In May 1918 she sublet it to Clare Annesley. Colette moved in on 9 September 1918 and stayed until June 1919. BR did not give up the lease until December 1923. See S. Turcon, “Russell Chambers, Other London Flats, and Country Homes, 1911–1923”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 150 (Fall 2014): 30–4. “Russell Chambers, Other London Flats, and Country Homes, 1911–1923”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 150 (Fall 2014): 30–4.

The Attic

The Attic was the nickname of the flat at 6 Mecklenburgh Square, London WC1, rented by Colette and her husband, Miles Malleson. The house which contained this flat is no longer standing. “The spacious and elegant facades of Mecklenburgh Square began to be demolished in 1950. The houses on the north side were banged into dust in 1958. The New Attic was entirely demolished” (“Letters to Bertrand Russell from Constance Malleson, 1916–1969”, p. 109; typescript in RA).

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.