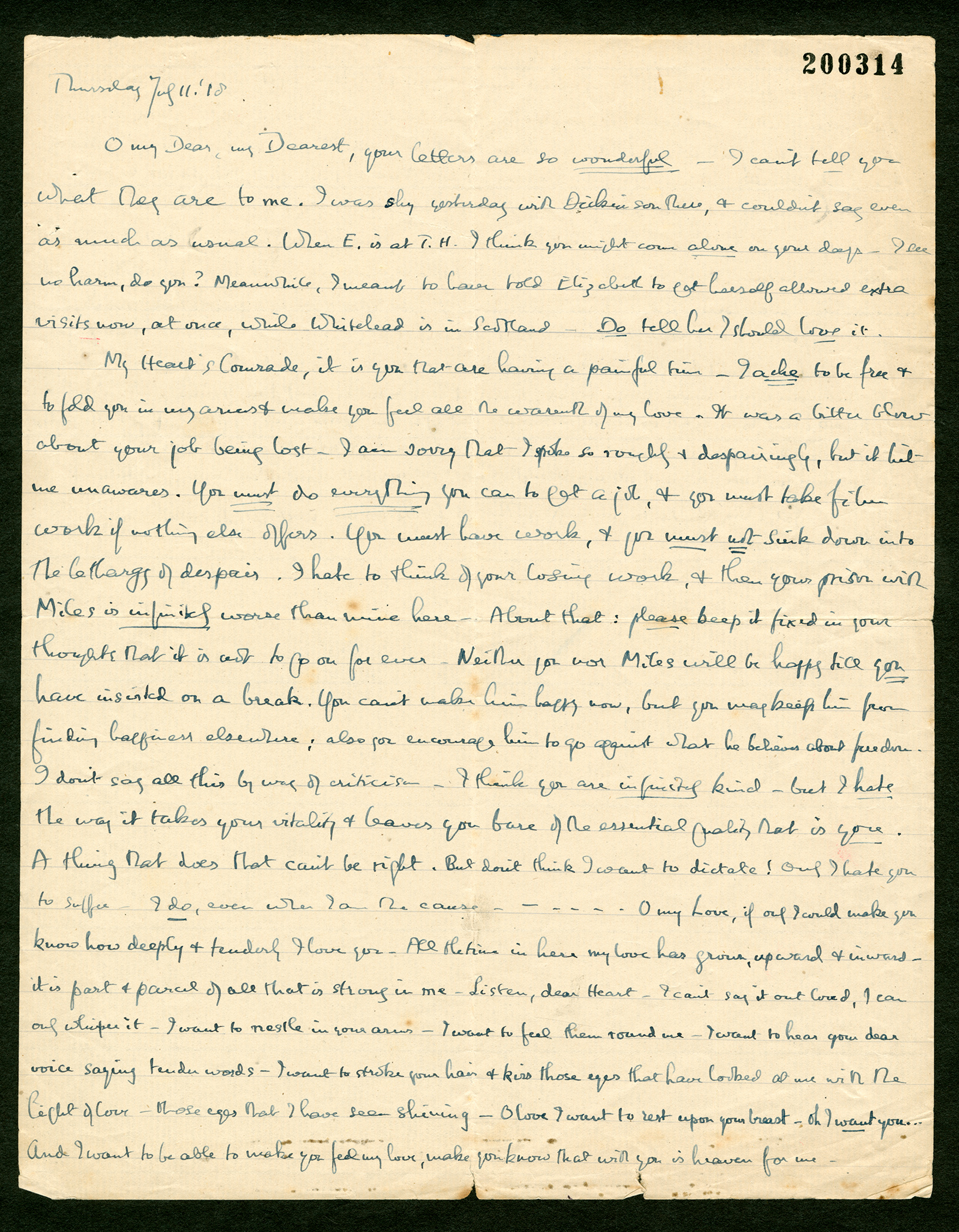

Brixton Letter 37

BR to Constance Malleson

July 11, 1918

- AL

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-37

BRACERS 19319

<Brixton Prison>1

Thursday July 11. ’18

O my Dear, my Dearest, your letters2 are so wonderful — I can’t tell you what they are to me. I was shy yesterday with Dickinson there,3 and couldn’t say even as much as usual. When E. is at T.H. I think you might come alone on your days. I see no harm, do you? Meanwhile, I meant to have told Elizabeth to get herself allowed extra visits now, at once, while Whitehead is in Scotland. Do tell her I should love it.

My Heart’s Comrade, it is you that are having a painful time. I ache to be free and to fold you in my arms and make you feel all the warmth of my love. It was a bitter blow about your job being lost.4 I am sorry that I spoke so roughly and despairingly, but it hit me unawares. You must do everything you can to get a job, and you must take film work if nothing else offers. You must have work, and you must not sink down into the lethargy of despair. I hate to think of your losing work, and then your prison with Miles is infinitely worse than mine here. About that: please keep it fixed in your thoughts that it is not to go on for ever. Neither you nor Miles will be happy till you have insisted on a break. You can’t make him happy now, but you may keep him from finding happiness elsewhere; also you encourage him to go against what he believes about freedom. I don’t say all this by way of criticism. I think you are infinitely kind — but I hate the way it takes your vitality and leaves you bare of the essential quality that is you. A thing that does that can’t be right. But don’t think I want to dictate! Only I hate you to suffer — I do, even when I am the cause.a

O my Love, if only I could make you know how deeply and tenderly I love you. All the time in here my love has grown, upward and inward — it is part and parcel of all that is strong in me. Listen, dear Heart — I can’t say it out loud, I can only whisper it. I want to nestle in your arms — I want to feel them round me — I want to hear your dear voice saying tender words — I want to stroke your hair and kiss those eyes that have looked at me with the light of love — those eyes that I have seen shining. O love I want to rest upon your breast — oh I want you.b And I want to be able to make you feel my love, make you know that with you is heaven for me.

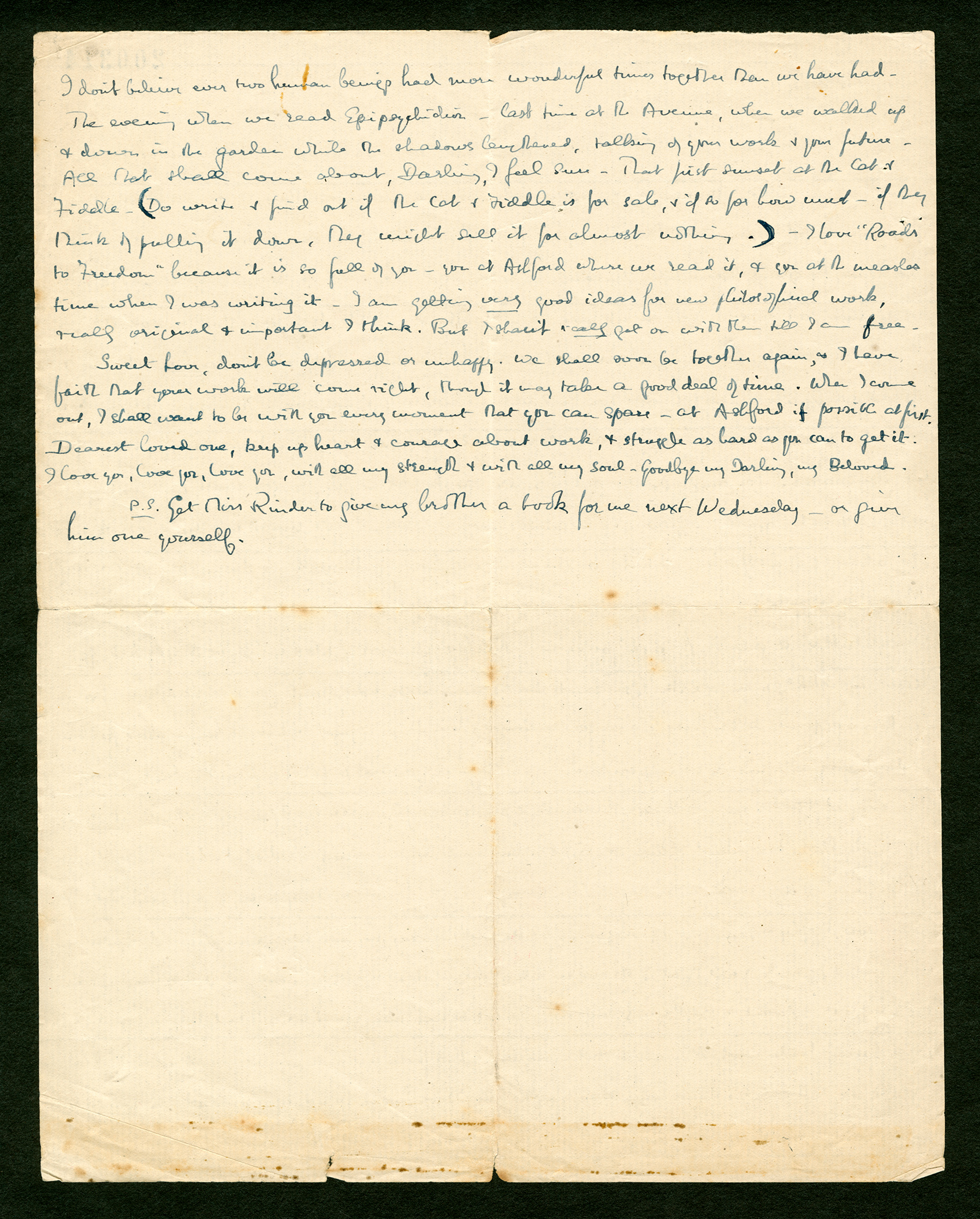

I don’t believe ever two human beings had more wonderful times together than we have had. The evening when we read Epipsychidion5 — last time at the Avenue, when we walked up and down in the garden while the shadows lengthened, talking of your work and your future. All that shall come about, Darling, I feel sure. That first sunset at the Cat and Fiddle.6 (Do write and find out if the Cat and Fiddle is for sale, and if so for how much — if they think of pulling it down, they might sell it for almost nothing.) — I love Roads to Freedom7 because it is so full of you — you at Ashford where we read it, and you at the measles time8 when I was writing it. I am getting very good ideas for new philosophical work, really original and important I think. But I shan’t really get on with them till I am free.

Sweet Love, don’t be depressed or unhappy. We shall soon be together again, and I have faith that your work will come right, though it may take a good deal of time. When I come out, I shall want to be with you every moment that you can spare — at Ashford if possible at first. Dearest loved one, keep up heart and courage about work, and struggle as hard as you can to get it. I love you, love you, love you, with all my strength and with all my soul. Goodbye my Darling, my Beloved.

P.S. Get Miss Rinder to give my brother a book for me9 next Wednesday — or give him one yourself.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the unsigned original in BR’s hand in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. The single sheet was folded twice.

- 2

your letters Colette had written him three letters earlier in July 1918. Her letter of 5 July (BRACERS 113137) was the most personal with memories of their time together. Her letter of 6 July (BRACERS 113138) mainly concerned hunger strikes. Another letter, also written on 6 July (BRACERS 113139), conveyed her impression of visiting him in prison as well as her memory of the time they spent in Ashford. It is not possible to know how many of these letters BR had received by the date of the present letter from him.

- 3

with Dickinson there BR’s old Cambridge friend, Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, had accompanied Colette on the previous day’s prison visit.

- 4

your job being lost No correspondence up to this point had mentioned a specific job. In a later letter Colette indicated that an American Colonel, J. Mitchell, whom she met at a luncheon party hosted by her mother at Claridges on 17 July, had told her that an underling of his had done her out of a job (18 July 1918, BRACERS 113143).

- 5

evening when we read Epipsychidion BR read Shelley’s poem Epipsychidion (1821) to Colette the first time they vacationed near Ashford Carbonel in August 1917. In his Autobiography BR recalled that he had read the poem to his first fiancée, Alys Pearsall Smith (1: 83).

- 6

the Cat and Fiddle … for sale The “Cat and Fiddle” pub in Derbyshire where Colette and BR vacationed twice, most recently just before he went into prison. See S. Turcon, “Then and Now: Bertie and Colette’s Escapes to the Peak District and Welsh Borderlands”, Russell 34 (2014): 117–30. In her letter of 5 July 1918 (BRACERS 113137) Colette had written: “Isn’t it awful to think we mayn’t be able to go to the Cat & Fiddle ever again.” She annotated this remark in her “Letters to Bertrand Russell from Constance Malleson, 1916–1969”, p. 243 (typescript in RA). “There was talk of closing or knocking down the Cat and Fiddle. The tenant-landlord was in fact obliged to move out, although Russell tried to help him by writing to the ground-landlord who happened to be Russell’s maternal uncle (Lord Stanley of Alderley).” The Cat & Fiddle did remain standing although Colette and BR never visited it again.

- 7

Roads to Freedom Published in the UK on 1 December 1918; in the US as Proposed Roads to Freedom in March 1919.

- 8

the measles timeColette had the measles in early March 1918.

- 9

give my brother a book for me The occasion for this instruction is unknown.

Textual Notes

A.N. Whitehead

Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947), Cambridge-educated mathematician and philosopher. From 1884 to 1910 he was a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, and lecturer in mathematics there; from 1911 to 1924 he taught in London, first at University College and then at the Imperial College of Science and Technology; in 1924 he took up a professorship in philosophy at Harvard and spent the rest of his life in America. BR took mathematics courses with him as an undergraduate, which led to a lifelong friendship. Whitehead’s first major work was A Treatise on Universal Algebra (1898), which treated selected mathematical theories as “systems of symbolic reasoning”. Like BR’s The Principles of Mathematics (1903), it was intended as the first of two volumes; but in 1900 he and BR discovered Giuseppe Peano’s work in symbolic logic, and each decided to set aside his projected second volume to work together on a more comprehensive treatment of mathematics using Peano’s methods. The result was the three volumes of Principia Mathematica (1910–13), which occupied the pair for over a decade. After Principia was published, Whitehead’s interests, like BR’s, turned to the empirical sciences and, finally, after his move to America, to pure metaphysics. See Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: the Man and His Work, 2 vols. (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins U. P., 1985–90).

Boismaison

Colette and BR vacationed at a house, The Avenue, owned by Mrs. Agnes Woodhouse and her husband, in the countryside near Ashford Carbonel, Shropshire, in August 1917. They nicknamed the house “Boismaison”. Agnes Woodhouse took in paying guests. Their first visit was idyllic. They returned for other vacations — in 1918 before he entered prison and in April 1919. Their plan to go soon after he got out of prison failed because their relationship faltered for a time. They discussed returning in the summer of 1919 — a booking was even made for 12–19 July — but in the end they didn’t go. See S. Turcon, “Then and Now: Bertie and Colette’s Escapes to the Peak District and Welsh Borderlands”, Russell 34 (2014): 117–30.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Elizabeth Russell

Elizabeth Russell, born Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941), was a novelist who in 1891 married Graf von Arnim-Schlagenthin. She became known as “Elizabeth”, the name she used in publishing Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898), and she remained widely known as Elizabeth von Arnim, although the Library of Congress catalogues her as Mary Annette (Beauchamp), Countess von Arnim. She was a widow when she married BR’s brother, Frank, on 11 February 1916. The marriage was quickly in difficulty; she left it for good in March 1919, but they were never divorced and she remained Countess Russell (becoming Dowager Countess after Frank’s death in 1931).

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).

G. Lowes Dickinson

Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson (1862–1932) was a Fellow and Lecturer of King’s College, Cambridge, where he had moved inside the same tight circle of friends as the undergraduate BR. According to BR, “Goldie” (as he was fondly known to intimates) “inspired affection by his gentleness and pathos” (Auto. 1: 63). As a scholar, his interests ranged across politics, history and philosophy. Also a passionate internationalist, Dickinson was an energetic promoter of future war prevention by a League to Enforce Peace. And he was a poet: BR copied three of his poems into “All the Poems That We Have Most Enjoyed Together”: Bertrand Russell’s Commonplace Book, ed. K. Blackwell (Hamilton, ON: McMaster U. Library P., 2018), pp. 8–13.

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Heart’s Comrade

Colette first called BR her “heart’s comrade” in her letter of 17 November 1916 (BRACERS 112964). On 9 December (BRACERS 112977), she explained: “I want you as comrade as well as lover.” On 9 April 1917 (BRACERS 19145), he reciprocated the sentiment for the first time. In a letter of 1 January 1918 (BRACERS 19260), BR was so upset with her that he could no longer call her “heart’s comrade”. After their relationship was patched up, he wrote on 16 February 1918 (BRACERS 19290): “I do really feel you now again my Heart’s Comrade.” The last time that BR expressed the sentiment in a letter to her was 26 August 1921 (BRACERS 19742).

Miles Malleson

Miles Malleson (1888–1969), actor and playwright, was born in Croydon, Surrey, the son of Edmund and Myrrha Malleson. He married his first wife, a fellow actor, Lady Constance Annesley (stage name, Colette O’Niel), in 1915. They had met at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts). Their marriage was an “open” one. In 1914 Miles enlisted in the City of London Fusiliers and was sent to Malta. He became ill and was discharged, unfit for further service. He became active in the No-Conscription Fellowship and wrote anti-war stage plays as well as a pamphlet, Cranks and Commonsense (1916). In the 1930s he began to write for the screen and act in films, in which he became a very well-known character actor, as well as continuing his stage career at the Old Vic in London. He married three times: his second marriage was to Joan Billson, a physician (married 1923, divorced 1940), with whom he had two children; his third wife was Tatiana Lieven, an actress (married 1946). He died in London in March 1969.

Priscilla, Lady Annesley

Priscilla, Lady Annesley (1870–1941), second wife of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl of Annesley (1831–1908) and mother of Lady Constance Malleson. Colette described her mother as “among the most beautiful women of her day” with a love of bright colours and walking (After Ten Years [London: Cape, 1931], pp. 12–14).

Telegraph House

Telegraph House, the country home of BR’s brother, Frank. It is located on the South Downs near Petersfield, Hants., and North Marden, W. Sussex. See S. Turcon, “Telegraph House”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 154 (Fall 2016): 45–69.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.