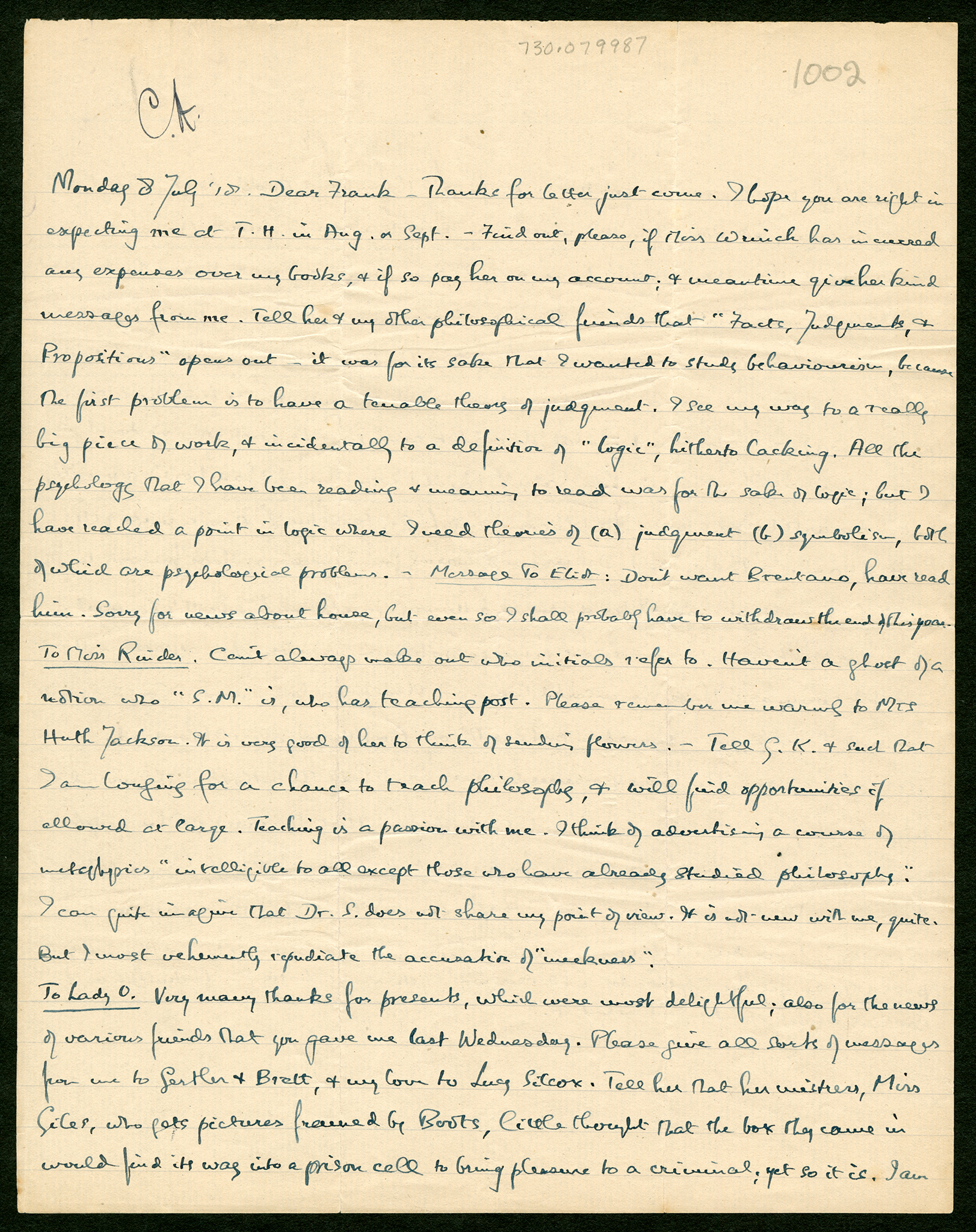

Brixton Letter 34

BR to Frank Russell

July 8, 1918

- ALS

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-34

BRACERS 46924

<Brixton Prison>1

Monday 8 July ’18.

Dear Frank

Thanks for letter2 just come. I hope you are right in expecting me at T.H.3 in Aug. or Sept. — Find out, please, if Miss Wrinch has incurred any expenses over my books, and if so pay her on my account; and meantime give her kind messages from me. Tell her and my other philosophical friends that “Facts, Judgments, and Propositions”4 opens out — it was for its sake that I wanted to study behaviourism, because the first problem is to have a tenable theory of judgment. I see my way to a really big piece of work, and incidentally to a definition of “logic”,5 hitherto lacking. All the psychology that I have been reading and meaning to read was for the sake of logic; but I have reached a point in logic where I need theories of (a) judgment (b) symbolism, both of which are psychological problems. — Message to Eliot: Don’t want Brentano, have read him.6 Sorry for news about house,7 but even so I shall probably have to withdraw the end of this year. To Miss Rinder. Can’t always make out who initials refer to. Haven’t a ghost of a notion who “S.M.”8 is, who has teaching post. Please remember me warmly to Mrs Huth Jackson.9 It is very good of her to think of sending flowers. — Tell G.K.10 and such that I am longing for a chance to teach philosophy, and will find opportunities if allowed at large. Teaching is a passion with me. I think of advertising a course of metaphysics “intelligible to all except those who have already studied philosophy.” I can quite imagine that Dr. S. does not share my point of view.11 It is not new with me, quite. But I most vehemently repudiate the accusation of “meekness”.12

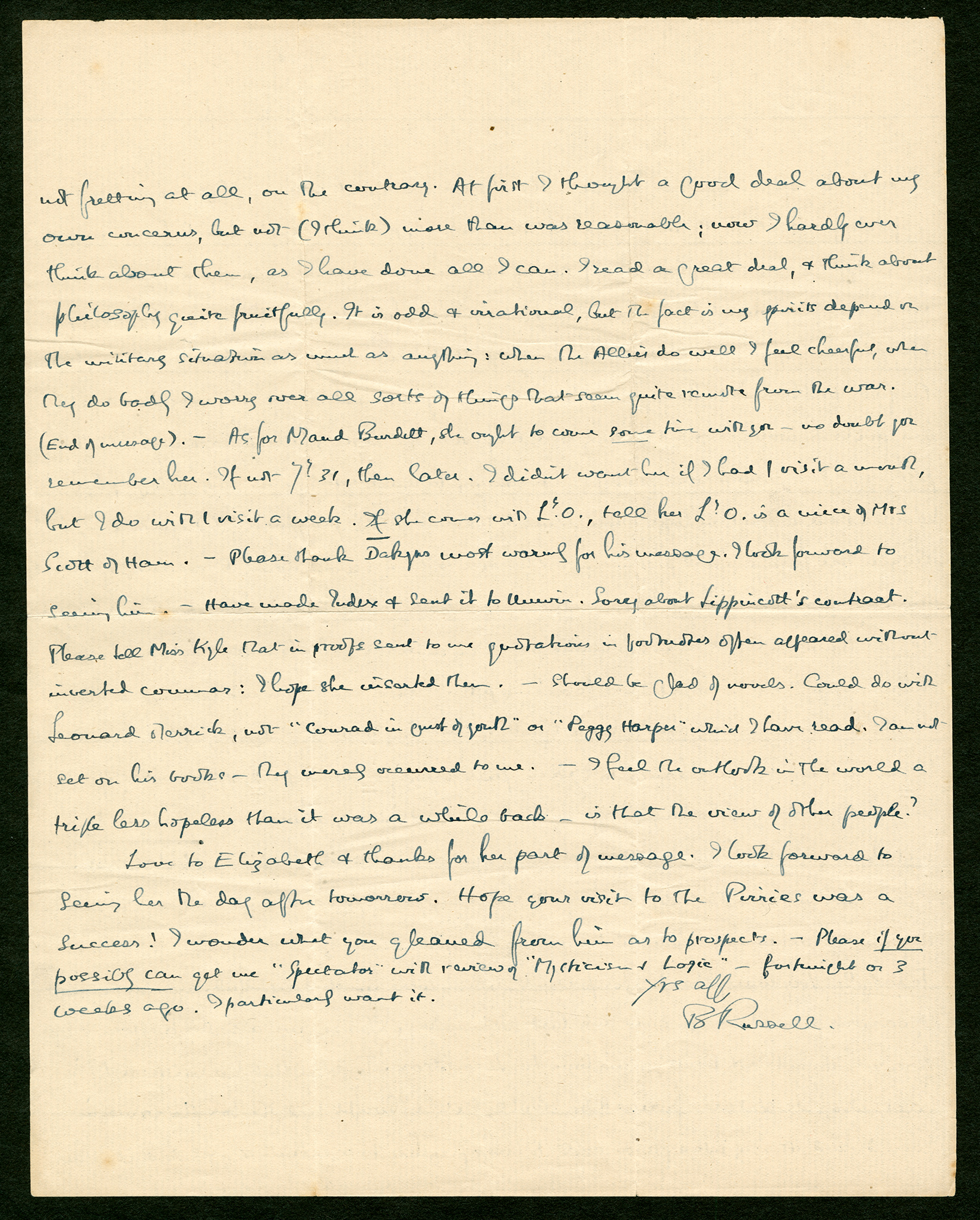

To Lady O. Very many thanks for presents, which were most delightful; also for the news of various friends that you gave me last Wednesday. Please give all sorts of messages from me to Gertler and Brett,13 and my love to Lucy Silcox. Tell her that her mistress, Miss Giles, who gets pictures framed by Boots,14 little thought that the box they came in would find its way into a prison cell to bring pleasure to a criminal; yet so it is. I am not fretting at all, on the contrary. At first I thought a good deal about my own concerns, but not (I think) more than was reasonable; now I hardly ever think about them, as I have done all I can. I read a great deal, and think about philosophy quite fruitfully. It is odd and irrational, but the fact is my spirits depend on the military situation as much as anything: when the Allies do well I feel cheerful, when they do badly I worry over all sorts of things that seem quite remote from the war. (End of message). — As for Maud Burdett, she ought to come some time with you — no doubt you remember her. If not Jy. 31, then later. I didn’t want her if I had 1 visit a month,15 but I do with 1 visit a week. If she comes with Ly. O., tell her Ly. O. is a niece of Mrs Scott of Ham.16 — Please thank Dakyns most warmly for his message.17 I look forward to seeing him. — Have made Index18 and sent it to Unwin. Sorry about Lippincott’s contract.19 Please tell Miss Kyle that in proofs sent to me quotations in footnotes often appeared without inverted commas: I hope she inserted them. — Should be glad of novels. Could do with Leonard Merrick,20 not Conrad in quest of youth or Peggy Harper which I have read. I am not set on his books — they merely occurred to me. — I feel the outlook in the world a trifle less hopeless than it was a while back — is that the view of other people?

Love to Elizabeth and thanks for her part of message. I look forward to seeing her the day after tomorrow. Hope your visit to the Pirries21 was a success! I wonder what you gleaned from him as to prospects. — Please if you possibly can get me Spectator with review of Mysticism and Logic22 — fortnight or 3 weeks ago. I particularly want it.

Yrs aff

B Russell.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the signed, handwritten original in the Frank Russell files in the Russell Archives. The letter covers both sides of a single sheet ruled on one side; it has three folds. It was an “official” letter, approved by “CH”, which are the initials of the Brixton Governor.

- 2

Thanks for letter Dated 5 July 1918 (BRACERS 116765).

- 3

T.H. BR’s getting to Telegraph House in August or September would have required an earlier release from Brixton than expected and that, in turn, would have required the success of Frank Russell’s efforts on his behalf.

- 4

“Facts, Judgments, and Propositions” These views were eventually published as “On Propositions: What They Are and How They Mean” (1919; 20 in Papers 8). Propositions, as BR now conceived them, were the objects of judgments (or belief). They were symbolic in nature because they represented possible states of affairs and psychology was involved because representation depended upon the mind. While he was in prison, BR changed his mind as to whether belief was the first problem for a theory of mind; he came to think that desire was the place to start. He discussed the matter at greater length in a message to Wrinch in Letter 51.

- 5

a really big piece of work … definition of “logic” Quite how big is revealed in his untitled outline of part of the project (Papers 8: App. II). (BR corrected the typescript, which was given the title “Bertrand Russell’s Notes on the New Work Which He Plans to Undertake”.) The outline, however, does not include the definition of logic. BR had considered the problem of defining logic in the final chapter of Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy (1919) but without coming to a satisfactory conclusion. Alas, he gives little further information as to what definition he now had in mind, except the remark that “Theory of true judgments most nearly gives what is in fact being studied in what we call ‘logic’” (18g of Papers 8: 266–7), which requires considerable elaboration to make it satisfactory.

- 6

Message to Eliot: Don’t want Brentano, have read him In his letter of 3 June 1918 (Letter 12; BRACERS 46917), BR had asked his brother if T.S. Eliot could recommend any books on “the psychology of belief — not causes, but analysis”. In a message conveyed by Frank’s letter of 5 July (BRACERS 46923), Eliot had suggested Franz Brentano’s “Classification of Psychical Phenomena” — in the original German presumably (Von der Klassifikation der psychischen Phänomene [Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, 1911]), as no English translation was in print. BR’s earlier psychological views had been heavily influenced by Brentano and his act–object school of psychology (which included two of BR’s teachers, G.F. Stout and James Ward), but in Analysis of Mind (1921) Brentano is one of the philosophers criticized.

- 7

house The Eliots rented a cottage at 31 West Street in the village of Marlow, Bucks., on 5 December 1917. BR had a financial obligation with regard to the rental, and he contributed furniture as well. (See note 12 to Letter 103.) Frank had relayed a message from Eliot. He had approached all possible acquaintances on sharing (or subletting) the cottage, but with no result.

- 8

S.M. “D.M.” was meant, for Dorothy Mackenzie (later Cousens).

- 9

remember me warmly to Mrs Huth Jackson Writer and society hostess Annabel (“Tiny”) Huth Jackson (née Grant Duff, 1870–1944) was a childhood friend of BR’s and a frequent visitor to Pembroke Lodge; she lived at York House, in Twickenham, on the opposite bank of the Thames. Although often terrorized by Frank, she remembered these excursions fondly and BR as a “solemn little boy in a blue velvet suit … always kind” (A Victorian Childhood [London: Methuen, 1932], p. 62). On 10 January 1917 she had communicated to BR her admiration of “the perfectly splendid stand you have made for principles against the whole of England” (BRACERS 1646).

- 10

G.K. George Kaufmann (later Adams, 1894–1963) was an “absolutist” C.O. who had been sentenced to two years’ hard labour early in 1917. He had previously studied chemistry at Christ’s College, Cambridge (from where he graduated in 1915) and served as president of the Cambridge University Socialist Society. On BR’s advice, he shifted his intellectual focus to projective geometry, while cultivating an enduring, parallel interest in the “spiritual science” of anthroposophy.

- 11

Dr. S.does not share my point of view The message from Rinder in Frank and Elizabeth Russell’s letter to BR of 5 July 1918 (BRACERS 46923) indicates that Letter 18 had been circulated to members of the No-Conscription Fellowship. Its Acting Chairman, the Quaker physician Dr. Alfred Salter, seems to have objected to BR’s advice that pacifist proselytizing was useless at present. “His robust optimism appears to me to have no solid foundation”, observed Rinder. Salter probably also disapproved of BR’s suggestion that imprisoned “absolutists” should now pledge to abstain from pacifist propaganda if such assurances secured their release and engagement in work of national importance. Many “absolutists” and most Quakers would have rejected civilian employment on such terms, and in all fairness Clifford Allen (no friend of NCF fanaticism) also disliked BR’s suggestion (see BRACERS 74282).

- 12

I … repudiate the accusation of “meekness” The “accusation” does not seem to have been levelled by Dr. Salter (see above), even though it could have been, in response to the political restraint recommended by BR in Letter 18 as a temporary tactic. In her own letter to BR written in early July, as opposed to the message in Frank and Elizabeth’s in which Salter is mentioned, Rinder had commented: “So glad to receive so good an account from your last visitors, only don’t grow too meek!” ([July 1918], BRACERS 79617). She may have been sharing a private joke with BR, derived from H.W. Massingham’s published response to BR’s conviction, which claimed that “Everybody who knows Mr. Russell knows that he would not hurt a fly, though he would freely give his body to be burned in any cause that he thought to be righteous one” (The Nation 23 [16 Feb. 1918]: 617). No doubt BR welcomed the backing of The Nation but so disliked the imputation of its editor that he remembered it over 40 years later in a passage comparing himself to Gilbert Murray. Far from being meek, BR then confessed, he had been prone to “outbreaks of savage indignation in which I wished to give pain to those whom I hated” (Gilbert Murray: an Unfinished Autobiography, ed. Jean Smith and Arnold Toynbee [London: Allen & Unwin, 1960], p. 208). See also Letter 31, in which BR insisted to Ottoline that “Hatred of some sort is quite necessary — it needn’t be towards people. But without some admixture of hate one becomes too soft and loses energy.”

- 13

Gertlerand Brett Bloomsbury artists Mark Gertler (1891–1939) and Dorothy Brett both enjoyed the patronage of Lady Ottoline Morrell, who even set up a studio for the latter during her three-year residence at Garsington Manor (1916–19). Gertler was also a frequent visitor to the Morrells’ Oxfordshire estate, where he too painted and was one of many C.O.s to be nominally employed there in alternative service as an agricultural labourer. See Letter 88 to Brett.

- 14

Miss Giles … Boots Nothing has been discovered about Miss Giles other than that she was a teacher at St. Felix, the girls’ school in Southwold, Suffolk, of which BR’s friend Lucy Silcox was headmistress. It seems that a box with her name on it was used by both Silcox and Ottoline to transport some (unidentified) gifts to BR. For many decades the Boots Pure Drug Company, the retail chemist, offered picture-framing (among other non-pharmaceutical services) at its numerous High Street branches.

- 15

if I had 1 visit a month In Letter 3 BR assumed that weekly first division visits, which he requested, would replace fortnightly visits.

- 16

Lady O. is a niece of Mrs Scott of Ham. Caroline Louisa Warren Scott, née Burnaby (1832–1918), was successively the widow of Charles Bentinck, Ottoline’s brother, and of Henry Warren Scott, and was a great-grandmother to Elizabeth II.

- 17

thank Dakyns … for his message On 27 June 1918, Arthur Dakyns, a close friend (see Letter 41), assured BR that he would “come from the ends of the earth” to see him, even “if only for a minute or two” (BRACERS 76251). He visited BR in Brixton on 17 July.

- 18

index BR had sent his index for Roads to Freedom to Unwin. A Russellian index may have humorous entries: this one includes “Chewing-gum” and “Button-hooks”.

- 19

Lippincott’s contract Despite various efforts by Frank and suggestions by BR, the contract could not be located in the latter’s papers at Gordon Square. However, a typed carbon copy, with seals, is in the Russell Archives (BRACERS 70492) and dated 11 October 1917.

- 20

Could do with Leonard Merrick A British actor turned writer, Leonard Merrick (née Miller, 1864–1939) was the author of some eleven novels, including Conrad in Quest of His Youth (1903) and The Position of Peggy Harper (1911).

- 21

your visit to the Pirries Frank had “business relations” with William James Pirrie (1847–1924, Baron Pirrie, 1906), which were mentioned but not specified in the letter of Friday, 5 July (BRACERS 116765) in which he notified his brother that he and Elizabeth would be spending the weekend with the chairman of the giant Belfast shipbuilding concern, Harland and Wolff, and his wife, Margaret (c.1857–1935). Ten years previously, the Canadian-born Ulster businessman had been the only other peer to vote with Frank on the second reading of the latter’s Divorce Law Reform Bill.

- 22

Spectator with review of Mysticism and LogicThe review, titled “Mysticism and Logic”, appeared in no. 4,695 (22 June 1918): 647–8. It had been brought to BR’s attention by Lucy Silcox (see BRACERS 80383). The anonymous reviewer, purportedly male, is identified in the marked copy of The Spectator as Mrs. C. Williams-Ellis, the former Amabel Strachey (1893–1984) and daughter of the Spectator’s editor, John St. Loe Strachey. Her brother was John Strachey. She was to be literary editor in 1922–23. In 1915 she married the architect Major Clough Williams-Ellis, who soon began building Portmeirion, the Italianate village close to BR’s final home in North Wales. In 1960 he prefaced a sci-fi anthology edited by Amabel, Vol. 1 of Out of This World. It’s not known, however, when they became friends or whether BR ever knew she was the reviewer. For the review’s content and BR’s response, see Letter 53.

57 Gordon Square

The London home of BR’s brother, Frank, 57 Gordon Square is in Bloomsbury. BR lived there, when he was in London, from August 1916 to April 1918, with the exception of January and part of February 1917.

Arthur Dakyns

Arthur Lindsay Dakyns (1883–1941), a barrister, had been befriended by BR when Dakyns was an Oxford undergraduate and the Russells were living at Bagley Wood. BR once described Dakyns to Gilbert Murray as “a disciple” (16 May 1905, BRACERS 79178) and wrote warmly of him to Lucy Donnelly as “the only person up here (except the Murrays) that I feel as a real friend” (1 Jan. 1906; Auto. 1: 181). During the First World War Dakyns enlisted in the Royal Army Medical Corps and served in France. BR had become acquainted with the H. Graham Dakyns family, who resided in Haslemere, Surrey, after he and Alys moved to nearby Fernhurst in 1896. He corresponded with both father and son.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Clifford Allen

(Reginald) Clifford Allen (1889–1939; Baron Allen of Hurtwood, 1932) was a socialist politician and publicist who joined the Cambridge University Fabian Society while studying at Peterhouse College (1908–11). After graduating he became active in the Independent Labour Party in London and helped establish a short-lived labour newspaper, the Daily Citizen. During the war Allen was an inspiring and effective leader of the C.O. movement as chairman of the No-Conscription Fellowship, which he co-founded with Fenner Brockway in November 1914. Court-martialled and imprisoned three times after his claim for absolute exemption from war service was rejected, Allen became desperately ill during his last spell of incarceration. He was finally released from the second division of Winchester Prison on health grounds in December 1917, but not before contracting the tuberculosis with which he was finally diagnosed in September 1918. He was dogged by ill health for the rest of his life. BR had enormous affection and admiration for Allen (e.g., 68 in Papers 13, 46 in Papers 14), a trusted wartime political associate. From February 1919 until March 1920 he even shared Allen’s Battersea apartment. A close friendship was soured, however, by Allen’s rejection of BR’s unforgiving critique of the Bolshevik regime, which both men witnessed at first hand with the British Labour Delegation to Russia in May 1920 (see Papers 15: 507). Yet Allen was far from revolutionary himself and did not even identify with the left wing of the ILP (which he chaired in the early 1920s). He was elevated to the peerage as a supporter of Ramsay MacDonald’s National Government, an administration despised by virtually the entire labour movement. Although Allen’s old intimacy with BR was never restored after the Russia trip, any lingering estrangement did not inhibit him from enrolling his daughter, Joan Colette (“Polly”) at the Russells’ Beacon Hill School.

Dorothy Brett

Dorothy Eugénie Brett (1883–1977), painter, benefitted from the patronage of Ottoline Morrell, who set up a studio for her at Garsington Manor. She lived there for three years (1916–19), becoming friends with J. Middleton Murry and Katherine Mansfield, among other visitors to the Morrells’ country home. Brett was the daughter of Liberal politician and courtier Viscount Esher. Notwithstanding her generous encouragement of Brett’s work, Ottoline could become impatient with her guest’s acute deafness, about which BR wrote compassionately in Letter 88. BR’s note below that letter in Auto. 2: 93 reads: “The lady to whom the above letter is addressed was a daughter of Lord Esher but was known to all her friends by her family name of Brett. At the time when I wrote the above letter, she was spending most of her time at Garsington with the Morrells. She went later to New Mexico in the wake of D.H. Lawrence.”

Dorothy Cousens

Dorothy Cousens (née Mackenzie) had been the fiancée of Graeme West, a soldier who had written to BR from the Front about politics. The Diary of a Dead Officer, a collection of his letters and memorabilia edited by Cyril Joad, was published in 1918 by Allen & Unwin. BR got to know Mackenzie after West was killed in action in April 1917 (she, “on the news of his death, became blind for three weeks” [BR’s note, Auto. 2: 71]) and provided some work for her and the man she married, Hilderic Cousens. Decades later she explained to K. Blackwell how she knew BR: “I had a break-down when most of my generation were either killed or in prison and Bertrand Russell was kind and helped me back to sanity” (29 July 1978, BRACERS 121877). She donated Letter 63 and a much later handwritten letter (BRACERS 55813), on the death of Hilderic, to the Russell Archives.

Dorothy Wrinch

Dorothy Maud Wrinch (1894–1976), mathematician, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. She studied mathematics and philosophy at Girton College, Cambridge, and came under BR’s influence in her second year when she took his course on mathematical logic. She taught mathematics at University College, London, 1918–21, and then at Oxford, 1922–30. Her first publications were in mathematical logic and philosophy, and during the 1920s she wrote on the philosophy of science. But in the 1930s her interests turned to mathematical biology and crystallography, and in 1935 she moved to the United States on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship and remained there for the rest of her life. Unfortunately, as a biologist she is best known for a long and stubborn controversy with Linus Pauling about the structure of proteins in which he was right and she was wrong. See Marjorie Senechal, I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science (New York: Oxford U. P., 2013). Chapter 7 is devoted to Wrinch’s interactions with BR in Brixton.

Dr. Alfred Salter

Dr. Alfred Salter (1873–1945), socialist and pacifist physician, replaced BR as Acting Chairman of the NCF in January 1918. For two decades he had been dedicated both professionally and politically to the working-class poor of Bermondsey. In 1898 Salter moved there into a settlement house founded by the Rev. John Scott Lidgett to minister to the health, social and educational needs of this chronically deprived borough in south-east London. In establishing a general practice in Bermondsey, Salter forsook the very real prospect of advancement in the medical sciences (at which he had excelled as a student at Guy’s). Shortly after his marriage to fellow settlement house worker Ada Brown in 1900, the couple joined the Society of Friends and Salter became active in local politics as a Liberal councillor. In 1908 he became a founding member of the Independent Labour Party’s Bermondsey branch and twice ran for Parliament there under its banner before winning the seat for the ILP in 1922. Although he lost it the following year, he was again elected in October 1924 and represented the constituency for the last twenty years of his life, during which he remained a consistently strong pacifist voice inside the ILP. Salter was an indefatigable organizer whose steely political will and fixed sense of purpose made him, in BR’s judgement, inflexible and doctrinaire when it came to the nuances of conscientious objection. See Oxford DNB and A. Fenner Brockway, Bermondsey Story: the Life of Alfred Salter (London: Allen & Unwin, 1949).

Elizabeth Russell

Elizabeth Russell, born Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941), was a novelist who in 1891 married Graf von Arnim-Schlagenthin. She became known as “Elizabeth”, the name she used in publishing Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898), and she remained widely known as Elizabeth von Arnim, although the Library of Congress catalogues her as Mary Annette (Beauchamp), Countess von Arnim. She was a widow when she married BR’s brother, Frank, on 11 February 1916. The marriage was quickly in difficulty; she left it for good in March 1919, but they were never divorced and she remained Countess Russell (becoming Dowager Countess after Frank’s death in 1931).

Eva Kyle

Eva Kyle ran a typing service. She did work for the No-Conscription Fellowship and took BR’s dictation of his book, Roads to Freedom, in the early months of 1918. He annotated a letter from her: “She was an admirable typist but very fat. We all agreed that she was worth her weight in gold, though that was saying a great deal.” Her prison letter to him is clever and amusing. She typed his major prison writings and apologized for the amount of the invoice when he emerged.

First Division

As part of a major reform of the English penal system, the Prison Act (1898) had created three distinct categories of confinement for offenders sentenced to two years or less (without hard labour) in a “local” prison. (A separate tripartite system of classification applied to prisoners serving longer terms of penal servitude in Britain’s “convict” prisons.) For less serious crimes, the courts were to consider the “nature of the offence” and the “antecedents” of the guilty party before deciding in which division the sentence would be served. But in practice such direction was rarely given, and the overwhelming majority of offenders was therefore assigned third-division status by default and automatically subjected to the harshest (local) prison discipline (see Victor Bailey, “English Prisons, Penal Culture, and the Abatement of Imprisonment, 1895–1922”, Journal of British Studies 36 [1997]: 294). Yet prisoners in the second division, to which BR was originally sentenced, were subject to many of the same rigours and rules as those in the third. Debtors, of whom there were more than 5,000 in local prisons in 1920, constituted a special class of inmate, whose less punitive conditions of confinement were stipulated in law rather than left to the courts’ discretion.

The exceptional nature of the first-division classification that BR obtained from the unsuccessful appeal of his conviction should not be underestimated. The tiny minority of first-division inmates was exempt from performing prison work, eating prison food and wearing prison clothes. They could send and receive a letter and see visitors once a fortnight (more frequently than other inmates could do), furnish their cells, order food from outside, and hire another prisoner as a servant. As BR’s dealings with the Brixton and Home Office authorities illustrate, prison officials determined the nature and scope of these and other privileges (for some of which payment was required). “The first division offenders are the aristocrats of the prison world”, concluded the detailed inquiry of two prison reformers who had been incarcerated as conscientious objectors: “The rules affecting them have a class flavour … and are evidently intended to apply to persons of some means” (Stephen Hobhouse and A. Fenner Brockway, eds., English Prisons To-day [London: Longmans, Green, 1922], p. 221). BR’s brother described his experience in the first division at Holloway prison, where he spent three months for bigamy in 1901, in My Life and Adventures (London: Cassell, 1923), pp. 286–90. Frank Russell paid for his “lodgings”, catered meals were served by “magnificent attendants in the King’s uniform”, and visitors came three times a week. In addition, the governor spent a half-hour in conversation with him daily. At this time there were seven first-class misdemeanants, who exercised (or sat about) by themselves. Frank concluded that he had “a fairly happy time”, and “I more or less ran the prison as St. Paul did after they had got used to him.” BR’s privileges were not quite so splendid as Frank’s, but he too secured a variety of special entitlements (see Letter 5).

Gilbert Murray

Gilbert Murray (1866–1957), distinguished classical scholar and dedicated liberal internationalist. He was Regius Professor of Greek at Oxford, 1908–36, and chair of the League of Nations Union, 1923–36. He and BR enjoyed a long and close friendship that was ruptured temporarily by bitter disagreement over the First World War. After Murray published The Foreign Policy of Sir Edward Grey, 1906–1915, in defence of Britain’s pre-war diplomacy, BR responded with a detailed critique, The Policy of the Entente, 1904–1914: a Reply to Professor Gilbert Murray (37 in Papers 13). Yet Murray still took the lead in campaigning to get BR’s sentence reassigned from the second to the first division and (later) in leading an appeal for professional and financial backing of an academic appointment for BR upon his release (the “fellowship plan”, which looms large in his prison correspondence). BR was still thankful for Murray’s exertions some 40 years later. See his portrait of Murray, “A Fifty-Six Year Friendship”, in Murray, An Unfinished Autobiography with Contributions by His Friends, ed. Jean Smith and Arnold Toynbee (London: Allen & Unwin, 1960).

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Governor of Brixton Prison / Carleton Haynes

Captain Carleton Haynes (1858–1945), the Governor of Brixton Prison in 1918, was a retired army officer and a cousin of BR’s acquaintance, the radical lawyer and author E.S.P. Haynes. In March 1919 BR sent Haynes, in jest, a copy (now in the Russell Archives) of his newly published Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy — so that the governor’s collection of works written by inmates while under his charge would “not ... be incomplete” (BRACERS 123167).

H.W. Massingham

H.W. Massingham (1860–1924), radical journalist and founding editor in 1907 of The Nation, a publication which superseded The Speaker and soon became Britain’s foremost Liberal weekly. Almost immediately the editor of the new periodical started to host a weekly luncheon (usually at the National Liberal Club), which became a vital forum for the exchange of “New Liberal” ideas and strategies between like-minded politicians, publicists and intellectuals (see Alfred F. Havighurst, Radical Journalist: H.W. Massingham, 1860–1924 [Cambridge: U. P., 1974], pp. 152–3). On 4 August 1914, BR attended a particularly significant Nation lunch, at which Massingham appeared still to be in favour of British neutrality (see Papers 13: 6) — which had actually ended at the stroke of midnight. By the next day, however, Massingham (like many Radical critics of Britain’s pre-war diplomacy) had come to accept the case for military intervention, a position he maintained (not without misgivings) for the next two years. Massingham was still at the helm of the Nation when it merged with the more literary-minded Athenaeum in 1921; he finally relinquished editorial control two years later. In 1918 he served on Miles and Constance Malleson’s Experimental Theatre Committee.

Lucy Silcox

Lucy Mary Silcox (1862–1947), headmistress of St. Felix school in Southwold, Suffolk (1909–26), feminist, and long-time friend of BR’s, whom he had known since at least 1906. On a letter from her, he wrote that she was “one of my dearest friends until her death ” (BR’s note, BRACERS 80365). After learning of BR’s conviction and sentencing by the Bow St. magistrate, a distraught Silcox reported to him that she had been “shut out in such blackness and desolation” (2 Feb. 1918, BRACERS 80377). During BR’s imprisonment it was Silcox who brought to his attention the Spectator review of Mysticism and Logic. Years later (in 1928), when BR and Dora Russell had launched Beacon Hill School, Silcox came with Ottoline Morrell to visit it.

Maud Burdett

Maud Clara Frances Burdett (1872–1951) and BR were childhood playmates and had remained in intermittent contact ever since. She was a daughter of Sir Francis Burdett, 7th Baronet, whose family home in Richmond was close to Pembroke Lodge where BR grew up. Sensing her keen intelligence, BR was disappointed when Maud’s conventional mother and sister dissuaded her from entering Newnham College, Cambridge. BR’s anti-war stand later caused her “acute pain”, she wrote him on 29 April 1918 (BRACERS 75326), but this political disagreement did not deter her from wishing to visit him in Brixton. Although BR felt somewhat duly-bound to receive her, it is not clear that he ever did.

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

Stanley Unwin

Stanley Unwin (1884–1968; knighted in 1946) became, in the course of a long business career, an influential figure in British publishing and, indeed, the book trade globally — for which he lobbied persistently for the removal of fiscal and bureaucratic impediments to the sale of printed matter (see his The Truth about a Publisher: an Autobiographical Record [London: Allen & Unwin, 1960], pp. 294–304). In 1916 Principles of Social Reconstruction became the first of many BR titles to appear under the imprint of Allen & Unwin, with which his name as an author is most closely associated. Along with G.D.H. Cole, R.H. Tawney and Harold Laski, BR was notable among several writers of the Left on the publishing house’s increasingly impressive list of authors. Unwin himself was a committed pacifist who conscientiously objected to the First World War but chose to serve as a nurse in a Voluntary Aid Detachment. With occasional departures, BR remained with the company for the rest of his life (and posthumously), while Unwin also acted for him as literary agent with book publishers in most overseas markets.

T.S. Eliot

The poet and critic Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888–1965) was a student of BR’s at Harvard in 1914. BR had sensed his ability, especially “a certain exquisiteness of appreciation” (to Lucy Donnelly, 11 May 1914; SLBR 1: 491), but did not see a genius in embryo. After Eliot travelled to England later the same year, to study philosophy at Oxford under H.H. Joachim, BR became something of a father figure to the younger man. He also befriended Eliot’s (English) wife, Vivienne, whom he had hastily married in 1915 and with whom BR may have had an affair the following year. BR shared his Bloomsbury apartment (at 34 Russell Chambers) with the couple for more than a year after their marriage, and jointly rented a property with them in Marlow, Bucks. (see Letter 78). He further eased Eliot’s monetary concerns by arranging paid reviewing for him and giving him £3,000 in debentures from which BR was reluctant, on pacifist grounds, to collect the income (Auto. 2: 19). Eliot’s financial security was much improved by obtaining a position at Lloyd’s Bank in 1917, but during BR’s imprisonment he faced uncertainty of a different kind as the shadow of conscription loomed over him (see, e.g., Letter 27). Nine years after the war ended Eliot returned the securities (BRACERS 76480).

Telegraph House

Telegraph House, the country home of BR’s brother, Frank. It is located on the South Downs near Petersfield, Hants., and North Marden, W. Sussex. See S. Turcon, “Telegraph House”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 154 (Fall 2016): 45–69.

The J.B. Lippincott Company

J.B. Lippincott Company, founded in 1836, was one of the world’s largest publishers. How it came to approach BR in 1917 is unknown, but it followed upon the success of the Century Company’s US publication of Why Men Fight (1917), the retitled Principles of Social Reconstruction (1916). See Letter 21, note 6.

The Nation

A political and literary weekly, 1907–21, edited for its entirety by H.W. Massingham before it merged with The Athenaeum and then The New Statesman. BR regularly contributed book reviews, starting in 1907. During his time at Brixton, he published there a book review (14 in Papers 8; mentioned in Letters 4 and 102) and a letter to the editor (Letter 39). In August 1914 The Nation hastily abandoned its longstanding support for British neutrality, rejecting an impassioned defence of this position written by BR on the day that Britain declared war (1 in Papers 13). For the next two years the publication gave its editorial backing (albeit with mounting reservations) to the quest for a decisive Allied victory. At the same time, it consistently upheld civil liberties against the encroachments of the wartime state, and by early 1917 had started calling for a negotiated peace as well. The Nation had recovered its dissenting credentials, but for allegedly “defeatist” coverage of the war was hit with an export embargo imposed in March 1917 by Defence of the Realm Regulation 24B.

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).