Brixton Letter 31

BR to Ottoline Morrell

July 2, 1918

- ALS

- Texas

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-31

BRACERS 18679

<Brixton Prison>1

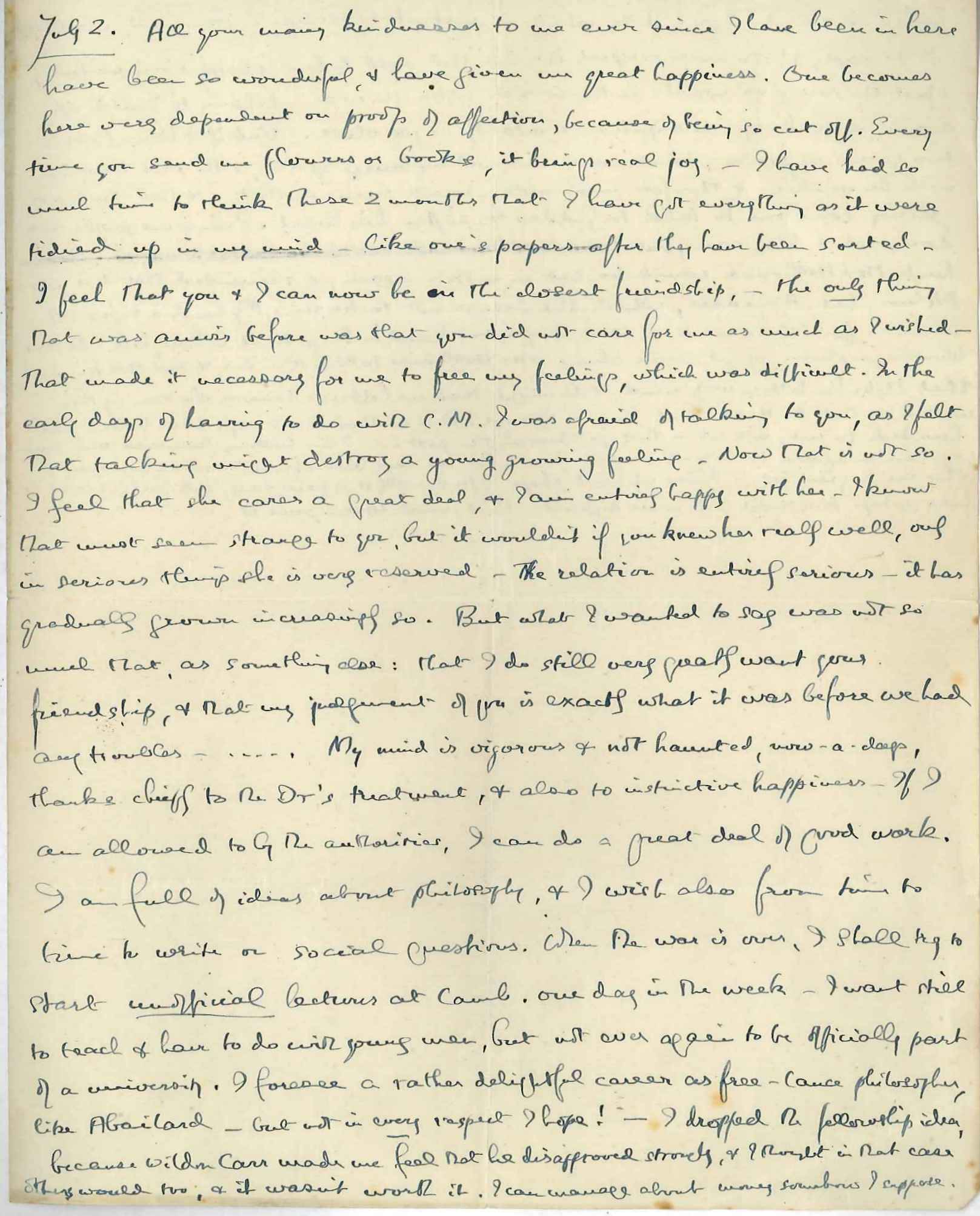

July 2.

All your many kindnesses to me ever since I have been in here have been so wonderful, and have given me great happiness. One becomes here very dependent on proofs of affection, because of being so cut off. Every time you send me flowers or books, it brings real joy. — I have had so much time to think these 2 months that I have got everything as it were tidied up in my mind — like one’s papers after they have been sorted. I feel that you and I can now be in the closest friendship, — the only thing that was amiss before was that you did not care for me as much as I wished — that made it necessary for me to free my feelings, which was difficult. In the early days of having to do with C.M.2 I was afraid of talking to you, as I felt that talking might destroy a young growing feeling. Now that is not so. I feel that she cares a great deal, and I am entirely happy with her. I know that must seem strange to you, but it wouldn’t if you knew her really well, only in serious things she is very reserved. The relation is entirely serious — it has gradually grown increasingly so. But what I wanted to say was not so much that, as something else: that I do still very greatly want your friendship, and that my judgment of you is exactly what it was before we had any troubles. …

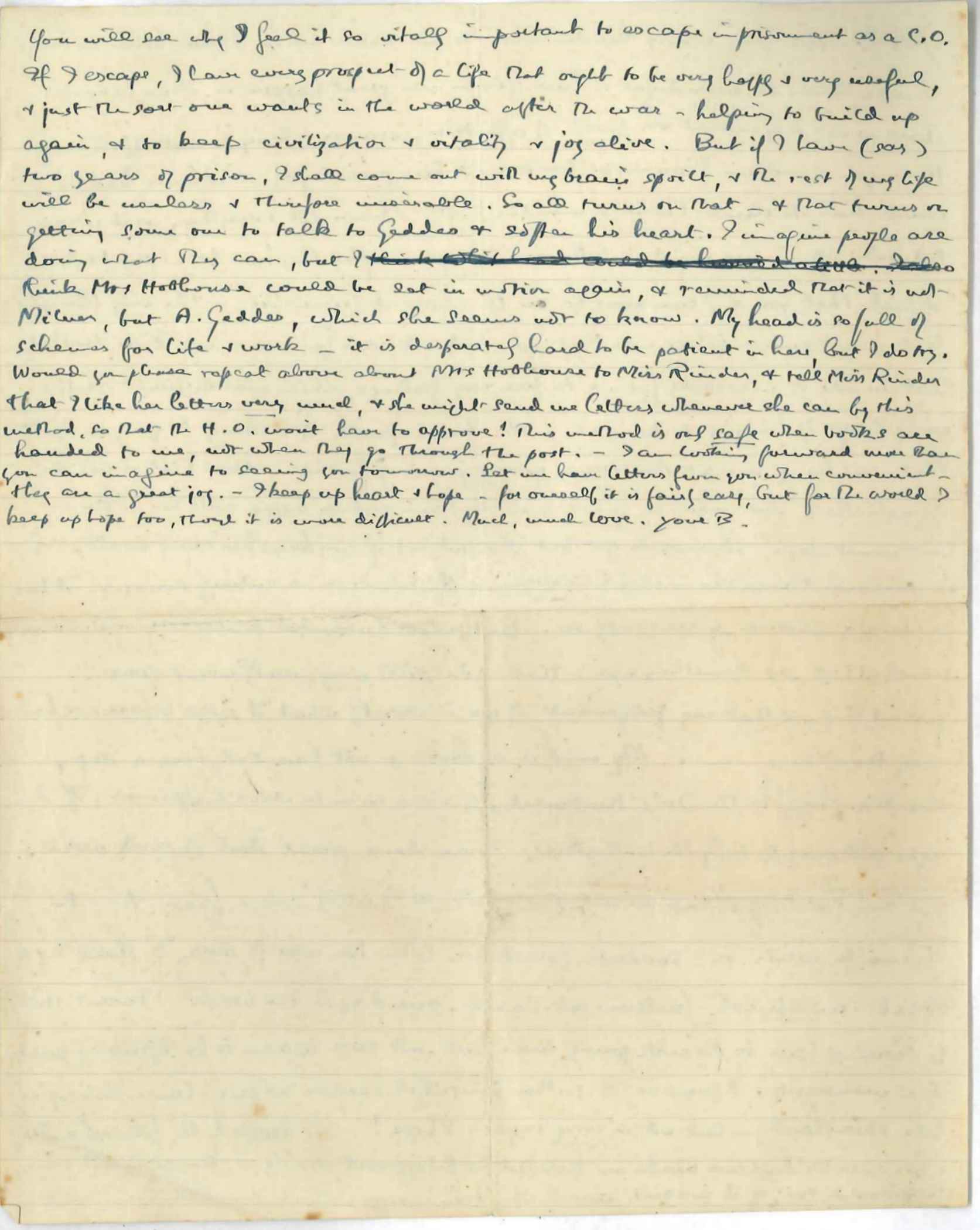

My minda is vigorous and not haunted, now-a-days, thanks chiefly to the Dr’s treatment,3 and also to instinctive happiness. If I am allowed to by the authorities, I can do a great deal of good work. I am full of ideas about philosophy, and I wish also from time to time to write on social questions. When the war is over, I shall try to start unofficial lectures at Camb. one day in the week. I want still to teach and have to do with young men, but not ever again to be officially part of a university.4 I foresee a rather delightful career as free-lance philosopher, like Abailard — but not in every respect5 I hope! — I dropped the fellowship idea, because Wildon Carr made me feel that he disapproved strongly, and I thought in that case others would too, and it wasn’t worth it. I can manage about money somehow I suppose. You will see why I feel it so vitally important to escape imprisonment as a C.O.6 If I escape, I have every prospect of a life that ought to be very happy and very useful, and just the sort one wants in the world after the war — helping to build up again, and to keep civilization and vitality and joy alive. But if I have (say) two years of prison, I shall come out with my brain spoilt, and the rest of my life will be useless and therefore miserable. So all turns on that — and that turns on getting some one to talk to Geddes7 and soften his heart. I imagine people are doing what they can, but I think Mrs Hobhouseb could be set in motion again, and reminded that it is not Milner,8 but A. Geddes, which she seems not to know. My head is so full of schemes for life and work — it is desperately hard to be patient in here, but I do try. Would you please repeat above about Mrs Hobhouse to Miss Rinder, and tell Miss Rinder that I like her letters9 very much, and she might send me letters whenever she can by this method,10 so that the H.O.11 won’t have to approve! This method is only safe when books are handed to me, not when they go through the post. — I am looking forward more than you can imagine to seeing you tomorrow. Let me have letters from you when convenient — they are a great joy. — I keep up heart and hope — for oneself it is fairly easy, but for the world I keep up hope too, though it is more difficult. Much, much love.

Your

B.

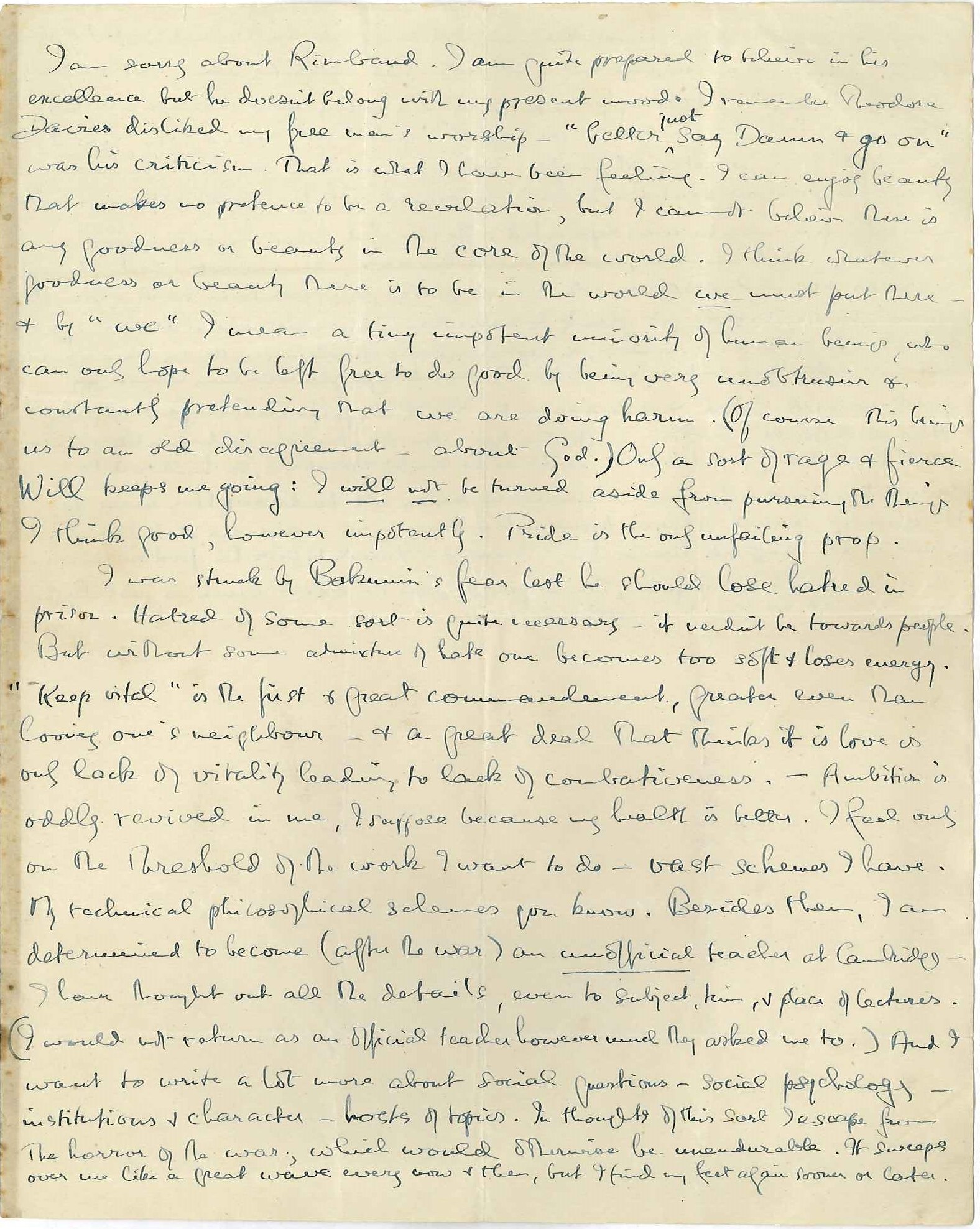

I am sorry about Rimbaud.12 I am quite prepared to believe in his excellence but he doesn’t belong with my present mood. I remember Theodore Davies disliked my “Free Man’s Worship”13, c — “better just say Damn and go on” was his criticism. That is what I have been feeling. I can enjoy beauty that makes no pretence to be a revelation, but I cannot believe there is any goodness or beauty in the core of the world. I think whatever goodness or beauty there is to be in the world we must put there — and by “we” I mean a tiny impotent minority of human beings, who can only hope to be left free to do good by being very unobtrusive and constantly pretending that we are doing harm.14 (Of course this brings us to an old disagreement — about God.) Only a sort of rage and fierce Will keeps me going: I will not be turned aside from pursuing the things I think good, however impotently. Pride is the only unfailing prop.

I was struck by Bakunin’s fear lest he should lose hatred in prison.15 Hatred of some sort is quite necessary — it needn’t be towards people. But without some admixture of hate one becomes too soft and loses energy. “Keep vital” is the first and great commandment, greater even than loving one’s neighbour — and a great deal that thinks it is love is only lack of vitality leading to lack of combativeness. — Ambition is oddly revived in me, I suppose because my health is better. I feel only on the threshold of the work I want to do — vast schemes I have. My technical philosophical schemes you know. Besides them, I am determined to become (after the war) an unofficial teacher at Cambridge. I have thought out all the details, even to subject, time, and place of lectures. (I would not return as an official teacher however much they asked me to.)d And I want to write a lot more about social questions — social psychology — institutions and character — hosts of topics. In thoughts of this sort I escape from the horror of the war, which would otherwise be unendurable. It sweeps over me like a great wave every now and then, but I find my feet again sooner or later.

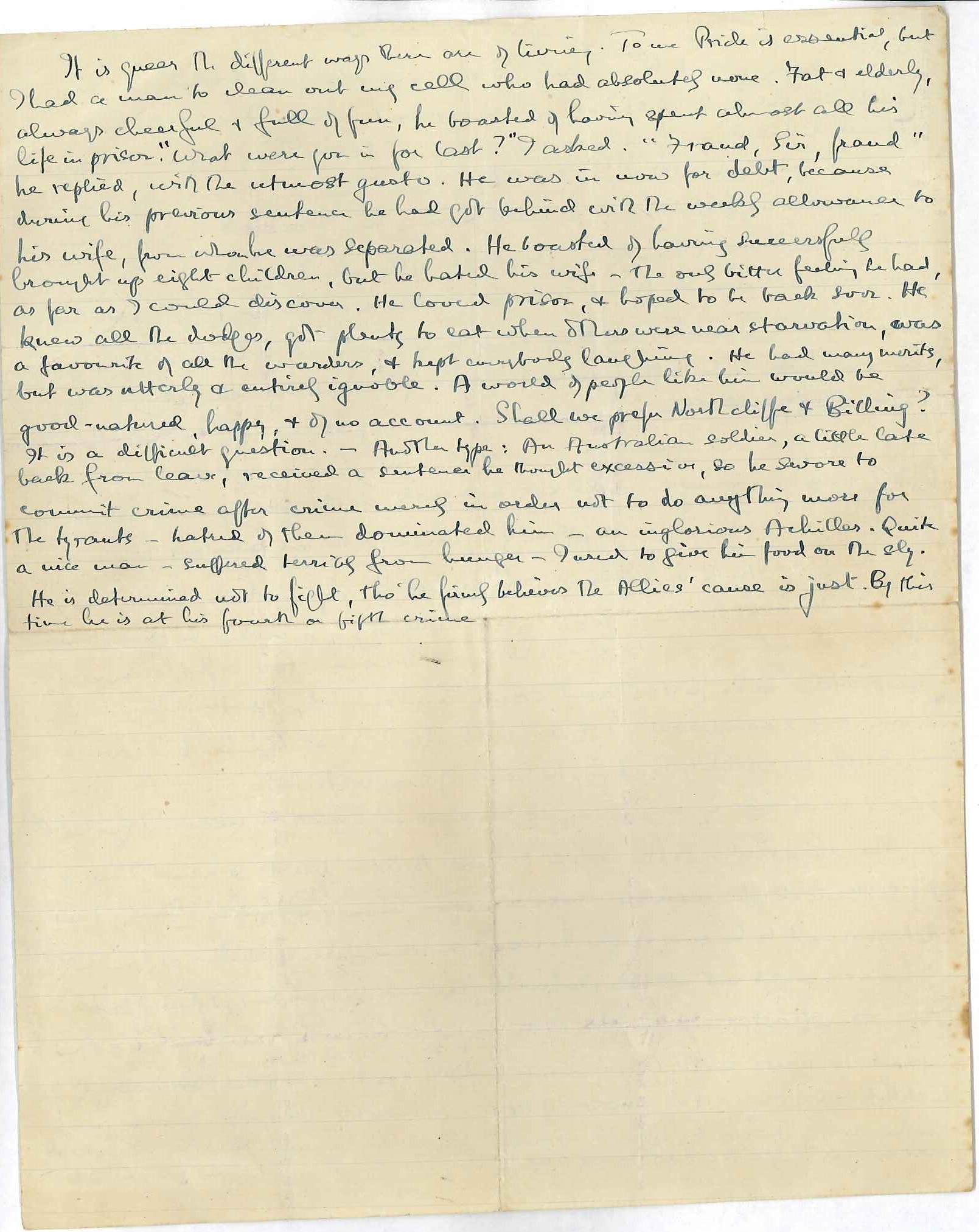

It is queer the different ways there are of living. To me Pride is essential, but I had a man to clean out my cell16 who had absolutely none. Fat and elderly, always cheerful and full of fun, he boasted of having spent almost all his life in prison. “What were you in for last?” I asked. “Fraud, Sir, fraud” he replied, with the utmost gusto. He was in now for debt, because during his previous sentence he had got behind with the weekly allowance to his wife, from whom he was separated. He boasted of having successfully brought up eight children, but he hated his wife — the only bitter feeling he had, as far as I could discover. He loved prison, and hoped to be back soon. He knew all the dodges, got plenty to eat when others were near starvation, was a favourite of all the warders, and kept everybody laughing. He had many merits, but was utterly and entirely ignoble. A world of people like him would be good-natured, happy, and of no account. Shall we prefer Northcliffe and Billing?17 It is a difficult question. — Another type: An Australian soldier, a little late back from leave,18 received a sentence he thought excessive, so he swore to commit crime after crime merely in order not to do anything more for the tyrants — hatred of them dominated him — an inglorious Achilles.19 Quite a nice man — suffered terribly from hunger — I used to give him food on the sly. He is determined not to fight, though he firmly believes the Allies’ cause is just. By this time he is at his fourth or fifth crime.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from a digital scan of BR’s initialled, handwritten original in the Morrell papers at the University of Texas at Austin. The sheet beginning “I am sorry about Rimbaud” was scanned with Letter 61, to which it manifestly did not belong. Instead, because of the continued discussion of Rimbaud’s merits, it surely belongs soon after Ottoline’s concluding mention of Rimbaud in her letter of 1 July 1918 (BRACERS 114748). BR had told her in a Letter 27 message that Rimbaud “means nothing to me”. The undated additional sheet may well have been written after Ottoline’s visit on 3 July.

- 2

early days of having to do with C.M.Ottoline expressed her shock at learning Colette had been BR’s mistress for nearly a year, in R. Gathorne-Hardy, ed., Ottoline at Garsington: Memoirs of Lady Ottoline Morrell, 1915–1918 (London: Faber and Faber, 1974, p. 178; see also p. 147). At the time she disguised her feelings and told BR she was glad for him (p. 178).

- 3

Dr’s treatment “For piles”.(BR’s note at BRACERS 119458.) The doctor was Elizabeth’s brother Sidney Beauchamp (1861–1921), M.B., B.Ch., physician. He became resident medical officer with the British delegation at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. He was killed in a motor-bus accident.

- 4

unofficial lectures at Camb. ... not ever officially part of a university Since being deprived of his lectureship in logic and the principles of mathematics by the Trinity College Council in July 1916, BR’s only realistic prospect of philosophical lecturing at Cambridge was on such ad hoc terms. He did not satisfy this ambition, but had already delivered two notable series of “unofficial” lectures in London(on philosophy of mathematics, from which his Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy emerged in prison, and “The Philosophy of Logical Atomism”). From May to June 1919 he presented a third series (“The Analysis of Mind”) at the same venue, Dr. Williams’ Library in Bloomsbury. Later in the year and in 1920 the series was doubled in length and given twice, at Dr. Williams’ Library and Morley College. Six months later BR’s Trinity College lectureship was restored, but almost his first action on accepting this five-year reappointment was to request a year’s leave of absence. In January 1921, while teaching in China, he tendered his resignation before ever becoming “officially part” of the university again (G.H. Hardy, Bertrand Russell and Trinity [Cambridge: Cambridge U. P., 1942, 1970], p. 57).

- 5

free-lance philosopher, like Abailard ...not in every respect The medieval philosopher Peter Abelard (c.1079–1142) was no conventional monastic scholar but lectured widely on both theology and logic — which repeatedly brought him into conflict with the Church. Yet BR was surely referring to the castration of Abelard by henchmen of the uncle of Héloïse, the lover whom he had secretly married, rather than to the heresy charges he faced later in life.

- 6

imprisonment as a C.O. BR was hinting at the possibility of prolonged detention in military or civil custody, should he be called up for military service after his release from Brixton, have his claim for absolute exemption rejected, and then refuse to undertake “alternative” war work. In April 1918 the upper-age limit for British conscripts had been raised from 40 to 50 (see Letter 6).

- 7

some one to talk to Geddes I.e., about the fellowship plan.

- 8

Mrs Hobhouse ... in motion again ... not Milner Margaret Hobhouse (1854–1921) was the mother of Stephen Hobhouse, a Quaker pacifist who in April 1917 had been sentenced to two years’ hard labour after being denied an absolute exemption from military service. But she was also the wife of a former Liberal Unionist M.P., while her son’s godfather was Alfred, Viscount Milner (1854–1925), the former colonial administrator and an influential member of Lloyd George’s War Cabinet. Although contemptuous of dissent and a “social-imperialist” who even favoured peacetime conscription, Milner was sympathetic to the plight of Hobhouse and other such religious C.O.s, whom he judged sincere and as neither “shirkers” nor “agitators”. At the prompting of Mrs. Hobhouse, Milner interceded discreetly on his godson’s behalf. Meanwhile, BR abetted the public campaign by secretly ghostwriting a letter (“Conscientious Objectors” [1917]) (Letter 12 was recently revised) to the New Statesman for Mrs. Hobhouse as well as a chapter of her book, ‘I Appeal unto Caesar’ (42 and 52 in Papers 14). In a notable political triumph for the C.O. movement, some 300 imprisoned “absolutists” were released before the year’s end. On 8 July 1918 Ottoline reported to BR that Rinder was planning to see Mrs. Hobhouse. Notwithstanding BR’s instruction, however, Ottoline insisted that Milner was the more influential contact: “Geddes would have to obey him and of course he is much more approachable than G. who is quite unhuman everyone says” (BRACERS 114749).

- 9

tell Miss Rinder that I like her letters Three of her letters survive from June 1918 (BRACERS 79614, 116585 and 79616).

- 10

by this method By smuggling letters into prison inside books and journals.

- 11

H.O. The Home Office, which was ultimately responsible for prison governance, although most administrative duties fell inside the remit of the Prison Commission, a statutory board created in 1877.

- 12

sorry about Rimbaud BR had already told Ottoline, also apologetically, in a message communicated to her by Frank, that the French symbolist poet Arthur Rimbaud (1854–1891) “means nothing to me” (Letter 27).

- 13

I remember Theodore Davies disliked my “Free Man’s Worship” BR was probably recalling a conversation with the late Theodore Llewelyn Davies (1871–1905), a close Cambridge friend who became a Treasury official. A journal (1 in Papers 12) kept by BR when he wrote his much-anthologized essay, “The Free Man’s Worship” (1903; 4 in ibid.), shows that he was in regular contact with both Theodore and his brother Crompton, who shared a Westminster home.

- 14

pretending that we are doing harm BR meant “harm” in the eyes of the minority, not from the point of view of the authorities (see Letter 18), with whom the minority pretended to cooperate.

- 15

Bakunin’s fear lest he should lose hatred in prison Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin (1814–1876) was first imprisoned in Saxony, where he was captured after leading the failed Dresden uprising of 1849. He was transferred into Austrian custody for a time before being incarcerated in Russia for six years. Although he suffered terribly, Bakunin “feared one thing above all”, according to James Guillaume, the French anthologizer of his writings whom BR quotes in the anarchism chapter of Roads to Freedom (London: Allen & Unwin, 1918), pp. 43–4: “He feared that he might cease to hate, that he might feel the sentiment of revolt which upheld him becoming extinguished in his heart, that he might come to pardon his persecutors and resign himself to his fate. But this fear was superfluous; his energy did not abandon him a single day, and he emerged from his cell the same man as when he entered.” The truth may have been more nuanced. While in St. Petersburg’s notorious Peter and Paul Fortress, Bakunin was ordered by Tsar Nicholas I to write a confession — a curious statement that remained unpublished until 1921, in which he justified his revolutionary past but also pleaded for clemency and blatantly appealed to the Tsar’s pan-Slavic chauvinism.

- 16

man to clean out my cell He is discussed in “Are Criminals Worse than Other People?” (1931; Mortals and Others [London: Routledge, 2009], p. 30).

- 17

Shall we prefer Northcliffe and Billing? In light of the ethical quandary posed by BR, it is worth noting that, in an earlier message to Ottoline, he had characterized Northcliffe as “sincere but evil” (Letter 7). Noel Pemberton Billing, aviator, Independent M.P. for East Hertfordshire (since March 1916), and publisher of The Imperialist, was another notorious Germanophobe. His flair for self-promotion had recently been demonstrated by his successful defence of a libel suit brought by a dancer in connection with Billing’s homophobic conspiracy theory — namely, that British public life was thoroughly debauched and that thousands of individuals were susceptible to blackmail by German spies.

- 18

Australian soldier, a little late back from leave He is also discussed in “Are Criminals Worse than Other People?”, Mortals and Others, pp. 29–30.

- 19

inglorious Achilles This mention of the renowned warrior from Greek mythology reminds one of the phrase “some mute inglorious Milton” from Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” (from which BR had used the first line, “The curfew tolls the knell of parting day”, as a propositional example in “On Denoting” [Papers 4: 421]).

Textual Notes

- a

My mind Preceded by a dash and five dots, which are taken, in the context of keeping to one smuggled sheet, as a paragraph break.

- b

think Mrs Hobhouse after deleted think Whitehead could be hurried a little.

- c

“Free Man’s Worship” Capitals and quotation marks were supplied editorially.

- d

(Of course this brings … God.) … (I would … me to.) The parentheses appear to be BR’s in the original; but in certain other letters they were supplied by Ottoline for her personal typescript of BR’s letters.

A.N. Whitehead

Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947), Cambridge-educated mathematician and philosopher. From 1884 to 1910 he was a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, and lecturer in mathematics there; from 1911 to 1924 he taught in London, first at University College and then at the Imperial College of Science and Technology; in 1924 he took up a professorship in philosophy at Harvard and spent the rest of his life in America. BR took mathematics courses with him as an undergraduate, which led to a lifelong friendship. Whitehead’s first major work was A Treatise on Universal Algebra (1898), which treated selected mathematical theories as “systems of symbolic reasoning”. Like BR’s The Principles of Mathematics (1903), it was intended as the first of two volumes; but in 1900 he and BR discovered Giuseppe Peano’s work in symbolic logic, and each decided to set aside his projected second volume to work together on a more comprehensive treatment of mathematics using Peano’s methods. The result was the three volumes of Principia Mathematica (1910–13), which occupied the pair for over a decade. After Principia was published, Whitehead’s interests, like BR’s, turned to the empirical sciences and, finally, after his move to America, to pure metaphysics. See Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: the Man and His Work, 2 vols. (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins U. P., 1985–90).

Annotations by BR

In the late 1940s, when BR was going through his archives, and in the 1950s when he was revising his Autobiography, he would occasionally annotate letters. He did this to sixteen of the Brixton letters. Links to them are gathered here for convenient access to these new texts. In the annotations to the letters they are always followed by “(BR’s note.)”

Letter 2, note 5 happy.

5, note 6 congratulations to G.J.

9, note 28 bit of Girondin history.

12, note 6 friend.

15, note 2 (the letter in general).

20, note 7 G.J.

31, note 3 Dr’s treatment.

40, notes 9, 10 Ld. G.L.G, Lady B’s.

44, note 14 S.S.

48, note 48 Mother Julian’s Bird.

57, notes 13, 16 Ld. Granville’s to Ly. B., bless that Dr. … seat of intellect.

70, note 15 Mrs Scott.

73, note 12 E.S.P. Haynes.

76, note 4 Cave.

85, note 2 Marsh on Rupert.

102, notes 23, 28 Woolley, K. Lonsdale.

General Annotations

Brett note from Auto. 2: 93

Cousens note from Auto. 2: 71

Kyle note with her letters to BR

Rinder note from Auto. 2: 88n.

Silcox note on BRACERS 80365

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.

David Lloyd George

Through ruthless political intrigue, David Lloyd George (1863–1945) emerged in December 1916 as the Liberal Prime Minister of a new and Conservative-dominated wartime Coalition Government. The “Welsh wizard” remained in that office for the first four years of the peace after a resounding triumph in the notorious “Coupon” general election of December 1918. BR despised the war leadership of Lloyd George as a betrayal of his Radical past as a “pro-Boer” critic of Britain’s South African War and as a champion of New Liberal social and fiscal reforms enacted before August 1914. BR was especially appalled by the Prime Minister’s stubborn insistence that the war be fought to a “knock-out” and by his punitive treatment of imprisoned C.O.s. For the latter policy, as BR angrily chastised Lloyd George at their only wartime meeting, “his name would go down to history with infamy” (Auto. 2: 24).

Elizabeth Russell

Elizabeth Russell, born Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941), was a novelist who in 1891 married Graf von Arnim-Schlagenthin. She became known as “Elizabeth”, the name she used in publishing Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898), and she remained widely known as Elizabeth von Arnim, although the Library of Congress catalogues her as Mary Annette (Beauchamp), Countess von Arnim. She was a widow when she married BR’s brother, Frank, on 11 February 1916. The marriage was quickly in difficulty; she left it for good in March 1919, but they were never divorced and she remained Countess Russell (becoming Dowager Countess after Frank’s death in 1931).

Fellowship Plan

Since the upper-age limit for compulsory military service had been increased to 50 in April 1918, BR was faced with the unnerving prospect of being conscripted after his release from Brixton. Early in his imprisonment he was already wondering about his “position when I emerge from here” (Letter 9). While his conviction was still under appeal, he had broached with Clifford Allen and Gilbert Murray the possibility of avoiding military service, not by asserting his conscientious objection to it, but by obtaining accreditation of his philosophical research as work of national importance (see note to Letter 24). The Pelham Committee, set up by the Board of Trade in March 1916, was responsible for the designation of essential occupations and recommending to the local tribunals, who adjudicated claims for exemption from military service, that C.O.s be considered for such positions. BR reasoned to Murray on 2 April that a dispensation to practise philosophy (as opposed to working outside his profession), would enable to him to “avoid prison without compromise” — i.e., of his political and moral opposition to conscription (BRACERS 52367). Although BR intended to withdraw from political work, he told Murray two days later, he would not promise to abstain from peace campaigning (BRACERS 52369). It should be noted that C.O.s who accepted alternative service in special Home Office camps were expressly prohibited from engaging in pacifist activities (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 231).

BR was far from sanguine about the prospect of success before a local tribunal. But he came to think (by early June) that his chances would be improved if his academic supporters interceded directly with the Minister of National Service, Sir Auckland Geddes. In addition, he calculated that such entreaties would be more effective if those acting on his behalf could secure and even endow a fellowship for him and thereby have “something definite to put before Geddes” (Letter 12; see also Letters 15 and 19). BR definitely wanted to rededicate himself to philosophy and would have welcomed a new source of income from academic employment (see Letter 22). But the “financial aspect was quite secondary”, he reminded Frank on 24 June (Letter 27); he was interested in the fellowship plan primarily as a safeguard against being called up, for teachers over 45 were not subject to the provisions of the recently amended Military Service Act. In the same letter, however, BR told his brother that “I wish it <the plan> dropped” on account of reservations expressed to him in person by Wildon Carr and A.N. Whitehead (see also Letter 31), two philosophers whom he respected but who seemed to doubt whether BR’s financial needs were as great as they appeared (see note to Letter 102).

Yet BR’s retreat was only temporary. On 8 August, he expressed to Ottoline a renewed interest in the initiative, and a few days later, she, her husband and Gladys Rinder met in London to discuss the matter. As Ottoline reported to BR, “we all felt that it was useless to wait for others to start and we decided that P. and I should go and see Gilbert M. and try and get him to work it with the Philosophers” (11 Aug. 1918, BRACERS 114754). BR probably wanted Murray to spearhead this lobbying (see also Letters 65 and 70) because of his political respectability and prior success in persuading professional philosophers to back an appeal to the Home Secretary for BR’s sentence to be served in the first division (see Letter 6). Murray did play a leading role but not until early the following month, when BR was anxious for the fellowship plan to succeed as his release date neared. The scheme finally gathered momentum after a meeting between Ottoline, Rinder and Carr on 6 September 1918, at which the philosopher and educationist T. Percy Nunn, another academic supporter of BR, was also present. Within a few days Murray had drafted a statement with an appeal for funds, which was endorsed by Carr, Whitehead, Nunn, Samuel Alexander, Bernard Bosanquet, G. Dawes Hicks, A.E. Taylor and James Ward. This memorial was then circulated in confidence to philosophers and others, but only after BR’s release from Brixton. (Financial pledges had already been made by a few of BR’s friends and admirers, notably Lucy Silcox and Siegfried Sassoon.) BR’s solicitor, J.J. Withers, became treasurer of this endowment fund, the goal of which was to provide BR with £150 or £200 per annum over three years. On 30 August BR had confessed to Ottoline that he did not want an academic position “very far from London” (Letter 89) and reiterated this desire in a message to Murray communicated by Rinder (Letter 97). On 6 September Rinder (BRACERS 79633) hinted that she already knew where the appointment would be, but there are no other indications that a particular establishment had been decided upon. Ultimately, no affiliation was contemplated for BR, so the memorial stated, because “in the present state of public feeling no ordinary university institution is likely to be willing to employ him as a teacher” (copy in BRACERS 56750). The circular talked instead of a “special Lectureship”, and the £100 BR received from the fund early in 1919 was explicitly issued as payment for lectures (on “The Analysis of Mind”; see syllabus, in Papers 9: App. III.1) that he would deliver that spring. BR’s solicitor also informed him that provision existed to pay him a further £100 for an autumn lecture course (see syllabus, ibid.: App. III.2), and Withers anticipated that these arrangements might “last two or three years” (2 Jan. 1919, BRACERS 81764). BR had already obtained a £50 gift from the fund in November 1918. Somewhat ironically, the critical importance of a teaching component to the fellowship plan — as insurance against conscription — was reduced by the authorities hesitating to hound BR any further after his imprisonment, and all but nullified by the end of the war a few weeks later. (There were no fresh call-ups, but the last of the C.O.s already in prison were not released until August 1919, and conscription remained in effect until April 1920.)

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

H. Wildon Carr

Herbert Wildon Carr (1857–1931), Professor of Philosophy at King’s College, London, from 1918 and Visiting Professor at the University of Southern California from 1925. Carr came to philosophy late in life after a lucrative career as a stockbroker. His philosophy was an idiosyncratic amalgam of Bergsonian vitalism and Leibnizian monadology, which, he thought, was supported by modern biology and the theory of relativity. He wrote books on Bergson and Leibniz at opposite ends of his philosophical career and a book on relativity in the middle. His philosophy would have made him an unlikely ally of BR’s, but it was Carr who organized BR’s two courses of public lectures, on philosophy of mathematics and the philosophy of logical atomism, which brought BR back to philosophy and improved his finances in 1917–18. Carr had great administrative talents, which he employed also on behalf of the Aristotelian Society during his long association with it. He was its president in 1916–18 and continued to edit its Proceedings until 1929.

Sir Auckland Geddes

Sir Auckland Geddes (1879–1954; 1st Baron Geddes, 1942) was returned unopposed as Conservative M.P. for Basingstoke in a by-election held in October 1917. Before this entry into civilian public life, he held the rank of Brigadier-General as director of recruiting at the War Office. He was an ardent champion of conscription even in peacetime and had a long-standing interest in the military, which he expressed before the war as a volunteer medical officer in the British Army Reserve. He had studied medicine and was Professor of Anatomy at McGill University, Montreal, when the outbreak of war prompted an immediate return to Britain in order to enlist. After a riding accident rendered Geddes unfit for front-line duties, he became a staff officer in France with a remit covering the supply and deployment of troops. He performed similar duties at the War Office until his appointment in August 1917 as a Minister of National Service with broad powers over both military recruitment and civilian labour. Geddes held two more Cabinet positions in Lloyd George’s post-war Coalition Government before his appointment in 1920 as British Ambassador to the United States. After returning from Washington on health grounds three years later, Geddes embarked upon a successful business career, becoming chairman in 1925 of the Rio Tinto mining company. See Oxford DNB.

Viscount Northcliffe

Alfred Charles Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe (1865–1922), press baron, whose stable of newspapers — especially the jingoistic Daily Mail — were militantly Germanophobic. For the last year of the war, Northcliffe promoted British war aims in an official capacity, as Director of Propaganda in Enemy Countries, although this government role did not inhibit his newspapers from challenging the political and military direction of the war effort.

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.