Brixton Letter 28

BR to Constance Malleson

June 25, 1918

- AL

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-28

BRACERS 19334

<Brixton Prison>1

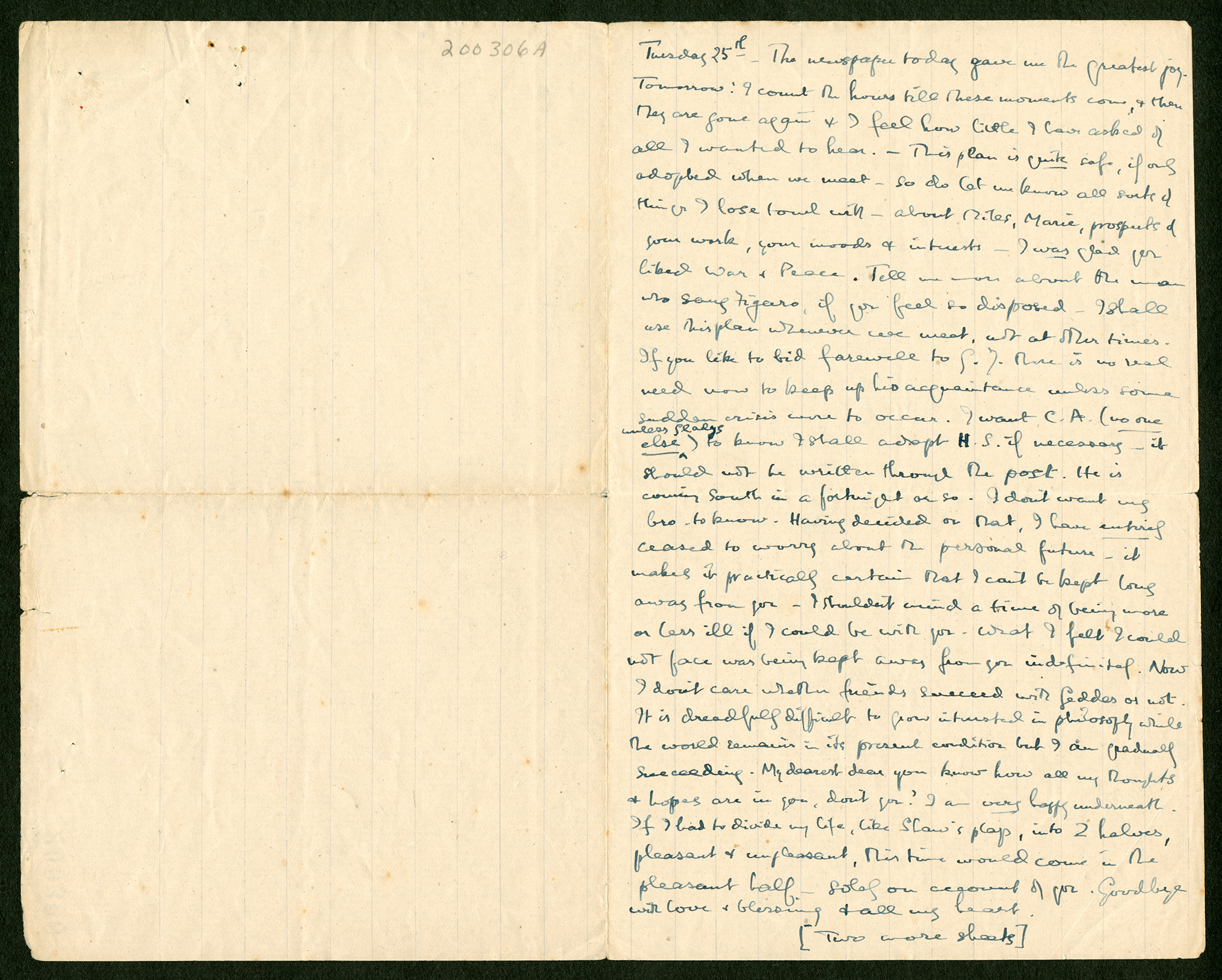

Tuesday 25th.

The newspaper today2 gave me the greatest joy. Tomorrow! I count the hours till these moments come,3 and then they are gone again and I feel how little I have asked of all I wanted to hear. — This plan is quite safe, if only adopted when we meet4 — so do let me know all sorts of things I lose touch with — about Miles, Marie,5 prospects of your work, your moods and interests. I was glad you liked War and Peace.6 Tell me more about the man who sang Figaro,7 if you feel so disposed. I shall use this plan whenever we meet, not at other times. If you like to bid farewell to G.J.8 there is no real need now to keep up his acquaintance unless some sudden crisis were to occur. I want C.A. (no one else unless Gladys)a to know I shall adopt H.S.9 if necessary — it should not be written through the post. He is coming South in a fortnight or so. I don’t want my brother to know. Having decided on that, I have entirely ceased to worry about the personal future — it makes it practically certain that I can’t be kept long away from you — I shouldn’t mind a time of being more or less ill if I could be with you. What I felt I could not face was being kept away from you indefinitely. Now I don’t care whether friends succeed with Geddes10 or not. It is dreadfully difficult to grow interested in philosophy while the world remains in its present condition but I am gradually succeeding. My dearest dear you know how all my thoughts and hopes are in you, don’t you? I am very happy underneath. If I had to divide my life, like Shaw’s plays,11 into 2 halves, pleasant and unpleasant, this time would come in the pleasant half — solely on account of you. Goodbye with love and blessing and all my heart.

[Two more sheets]12

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the unsigned, single-sheet original in BR’s hand in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. It is written on the verso of the letter of 21 June 1918 (Letter 24).

- 2

newspaper today There was a Times Personal placed this day by Colette as “G.J.”: “So lonely. You have all my love” (BRACERS 96084).

- 3

till these moments come When he had visitors at the prison.

- 4

This plan is quite safe, if only adopted when we meet The plan of hiding letters in the uncut pages of books which would be exchanged during prison visits.

- 5

Marie Marie Blanche was an actress and friend of Colette’s. In a message as “C.O’N” in a letter from Gladys Rinder to BR, 21 June 1918 (BRACERS 116615), Colette wrote that Marie had been ill, had had an operation, was now in a nursing home and getting better. In Letter 22 BR, clearly assuming that the “illness” was a pregnancy, asked if the child Marie was going to have was Miles’s.

- 6

liked War and PeaceColette, in a message as “G.J.”, made reference to some of Tolstoy’s characters (letter from Rinder, BRACERS 79616).

- 7

the man who sang Figaro Frederick Ranalow (1873–1953), a baritone, was born in Dublin and studied at the Royal Academy of Music. In a message as G.J. in a letter from Frank and Elizabeth Russell, 6 June 1918 (BRACERS 46918), Colette wrote: “At Manchester I made friends with Ranalow, who sings Figaro.” Colette had written more expansively about Ranalow two days earlier in a letter she later designated “official”, which BR did not receive (BRACERS 113134). “On my way up to Manchester I found myself in the same railway carriage as Frederick Ranalow (nice though naive) who sings in Figaro for <Sir Thomas> Beecham.” Thus BR’s query in this letter. Again, a response was not forthcoming until Colette’s letter of 26 July 1918 (BRACERS 113145): “Ranalow. But I never saw him again; and had told you all there was to tell in a previous letter. On tour one runs into theatre people in that way, specially on Sunday trains.…”

- 8

G.J. Pseudonym used by Colette in letters and in The Times Personals. Now that they could smuggle letters in and out of prison, one of their previous means of communicating — through the Times Personals column — was abandoned.

- 9

H.S. Hunger strike.

- 10

friends succeed with Geddes I.e., in promoting the fellowship plan.

- 11

like Shaw’s plays Shaw’s plays had been collected and published as Plays: Pleasant and Unpleasant (2 vols., 1898).

- 12

[Two more sheets] These sheets are no longer with this letter and, even if extant, could not be editorially identified.

Textual Notes

- a

unless Gladys Inserted.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Clifford Allen

(Reginald) Clifford Allen (1889–1939; Baron Allen of Hurtwood, 1932) was a socialist politician and publicist who joined the Cambridge University Fabian Society while studying at Peterhouse College (1908–11). After graduating he became active in the Independent Labour Party in London and helped establish a short-lived labour newspaper, the Daily Citizen. During the war Allen was an inspiring and effective leader of the C.O. movement as chairman of the No-Conscription Fellowship, which he co-founded with Fenner Brockway in November 1914. Court-martialled and imprisoned three times after his claim for absolute exemption from war service was rejected, Allen became desperately ill during his last spell of incarceration. He was finally released from the second division of Winchester Prison on health grounds in December 1917, but not before contracting the tuberculosis with which he was finally diagnosed in September 1918. He was dogged by ill health for the rest of his life. BR had enormous affection and admiration for Allen (e.g., 68 in Papers 13, 46 in Papers 14), a trusted wartime political associate. From February 1919 until March 1920 he even shared Allen’s Battersea apartment. A close friendship was soured, however, by Allen’s rejection of BR’s unforgiving critique of the Bolshevik regime, which both men witnessed at first hand with the British Labour Delegation to Russia in May 1920 (see Papers 15: 507). Yet Allen was far from revolutionary himself and did not even identify with the left wing of the ILP (which he chaired in the early 1920s). He was elevated to the peerage as a supporter of Ramsay MacDonald’s National Government, an administration despised by virtually the entire labour movement. Although Allen’s old intimacy with BR was never restored after the Russia trip, any lingering estrangement did not inhibit him from enrolling his daughter, Joan Colette (“Polly”) at the Russells’ Beacon Hill School.

Fellowship Plan

Since the upper-age limit for compulsory military service had been increased to 50 in April 1918, BR was faced with the unnerving prospect of being conscripted after his release from Brixton. Early in his imprisonment he was already wondering about his “position when I emerge from here” (Letter 9). While his conviction was still under appeal, he had broached with Clifford Allen and Gilbert Murray the possibility of avoiding military service, not by asserting his conscientious objection to it, but by obtaining accreditation of his philosophical research as work of national importance (see note to Letter 24). The Pelham Committee, set up by the Board of Trade in March 1916, was responsible for the designation of essential occupations and recommending to the local tribunals, who adjudicated claims for exemption from military service, that C.O.s be considered for such positions. BR reasoned to Murray on 2 April that a dispensation to practise philosophy (as opposed to working outside his profession), would enable to him to “avoid prison without compromise” — i.e., of his political and moral opposition to conscription (BRACERS 52367). Although BR intended to withdraw from political work, he told Murray two days later, he would not promise to abstain from peace campaigning (BRACERS 52369). It should be noted that C.O.s who accepted alternative service in special Home Office camps were expressly prohibited from engaging in pacifist activities (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 231).

BR was far from sanguine about the prospect of success before a local tribunal. But he came to think (by early June) that his chances would be improved if his academic supporters interceded directly with the Minister of National Service, Sir Auckland Geddes. In addition, he calculated that such entreaties would be more effective if those acting on his behalf could secure and even endow a fellowship for him and thereby have “something definite to put before Geddes” (Letter 12; see also Letters 15 and 19). BR definitely wanted to rededicate himself to philosophy and would have welcomed a new source of income from academic employment (see Letter 22). But the “financial aspect was quite secondary”, he reminded Frank on 24 June (Letter 27); he was interested in the fellowship plan primarily as a safeguard against being called up, for teachers over 45 were not subject to the provisions of the recently amended Military Service Act. In the same letter, however, BR told his brother that “I wish it <the plan> dropped” on account of reservations expressed to him in person by Wildon Carr and A.N. Whitehead (see also Letter 31), two philosophers whom he respected but who seemed to doubt whether BR’s financial needs were as great as they appeared (see note to Letter 102).

Yet BR’s retreat was only temporary. On 8 August, he expressed to Ottoline a renewed interest in the initiative, and a few days later, she, her husband and Gladys Rinder met in London to discuss the matter. As Ottoline reported to BR, “we all felt that it was useless to wait for others to start and we decided that P. and I should go and see Gilbert M. and try and get him to work it with the Philosophers” (11 Aug. 1918, BRACERS 114754). BR probably wanted Murray to spearhead this lobbying (see also Letters 65 and 70) because of his political respectability and prior success in persuading professional philosophers to back an appeal to the Home Secretary for BR’s sentence to be served in the first division (see Letter 6). Murray did play a leading role but not until early the following month, when BR was anxious for the fellowship plan to succeed as his release date neared. The scheme finally gathered momentum after a meeting between Ottoline, Rinder and Carr on 6 September 1918, at which the philosopher and educationist T. Percy Nunn, another academic supporter of BR, was also present. Within a few days Murray had drafted a statement with an appeal for funds, which was endorsed by Carr, Whitehead, Nunn, Samuel Alexander, Bernard Bosanquet, G. Dawes Hicks, A.E. Taylor and James Ward. This memorial was then circulated in confidence to philosophers and others, but only after BR’s release from Brixton. (Financial pledges had already been made by a few of BR’s friends and admirers, notably Lucy Silcox and Siegfried Sassoon.) BR’s solicitor, J.J. Withers, became treasurer of this endowment fund, the goal of which was to provide BR with £150 or £200 per annum over three years. On 30 August BR had confessed to Ottoline that he did not want an academic position “very far from London” (Letter 89) and reiterated this desire in a message to Murray communicated by Rinder (Letter 97). On 6 September Rinder (BRACERS 79633) hinted that she already knew where the appointment would be, but there are no other indications that a particular establishment had been decided upon. Ultimately, no affiliation was contemplated for BR, so the memorial stated, because “in the present state of public feeling no ordinary university institution is likely to be willing to employ him as a teacher” (copy in BRACERS 56750). The circular talked instead of a “special Lectureship”, and the £100 BR received from the fund early in 1919 was explicitly issued as payment for lectures (on “The Analysis of Mind”; see syllabus, in Papers 9: App. III.1) that he would deliver that spring. BR’s solicitor also informed him that provision existed to pay him a further £100 for an autumn lecture course (see syllabus, ibid.: App. III.2), and Withers anticipated that these arrangements might “last two or three years” (2 Jan. 1919, BRACERS 81764). BR had already obtained a £50 gift from the fund in November 1918. Somewhat ironically, the critical importance of a teaching component to the fellowship plan — as insurance against conscription — was reduced by the authorities hesitating to hound BR any further after his imprisonment, and all but nullified by the end of the war a few weeks later. (There were no fresh call-ups, but the last of the C.O.s already in prison were not released until August 1919, and conscription remained in effect until April 1920.)

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Marie Blanche

Marie Blanche (1891–1973) studied at the Academy of Dramatic Arts where she met Colette. She sang as well as acted and had a successful career on the London stage in the 1920s. A photograph of her appeared in The Times, 20 March 1923, p. 16.

Miles Malleson

Miles Malleson (1888–1969), actor and playwright, was born in Croydon, Surrey, the son of Edmund and Myrrha Malleson. He married his first wife, a fellow actor, Lady Constance Annesley (stage name, Colette O’Niel), in 1915. They had met at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts). Their marriage was an “open” one. In 1914 Miles enlisted in the City of London Fusiliers and was sent to Malta. He became ill and was discharged, unfit for further service. He became active in the No-Conscription Fellowship and wrote anti-war stage plays as well as a pamphlet, Cranks and Commonsense (1916). In the 1930s he began to write for the screen and act in films, in which he became a very well-known character actor, as well as continuing his stage career at the Old Vic in London. He married three times: his second marriage was to Joan Billson, a physician (married 1923, divorced 1940), with whom he had two children; his third wife was Tatiana Lieven, an actress (married 1946). He died in London in March 1969.

Sir Auckland Geddes

Sir Auckland Geddes (1879–1954; 1st Baron Geddes, 1942) was returned unopposed as Conservative M.P. for Basingstoke in a by-election held in October 1917. Before this entry into civilian public life, he held the rank of Brigadier-General as director of recruiting at the War Office. He was an ardent champion of conscription even in peacetime and had a long-standing interest in the military, which he expressed before the war as a volunteer medical officer in the British Army Reserve. He had studied medicine and was Professor of Anatomy at McGill University, Montreal, when the outbreak of war prompted an immediate return to Britain in order to enlist. After a riding accident rendered Geddes unfit for front-line duties, he became a staff officer in France with a remit covering the supply and deployment of troops. He performed similar duties at the War Office until his appointment in August 1917 as a Minister of National Service with broad powers over both military recruitment and civilian labour. Geddes held two more Cabinet positions in Lloyd George’s post-war Coalition Government before his appointment in 1920 as British Ambassador to the United States. After returning from Washington on health grounds three years later, Geddes embarked upon a successful business career, becoming chairman in 1925 of the Rio Tinto mining company. See Oxford DNB.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.