Brixton Letter 26

BR to Constance Malleson

June 24, 1918

- AL

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-26

BRACERS 19315

<Brixton Prison>1

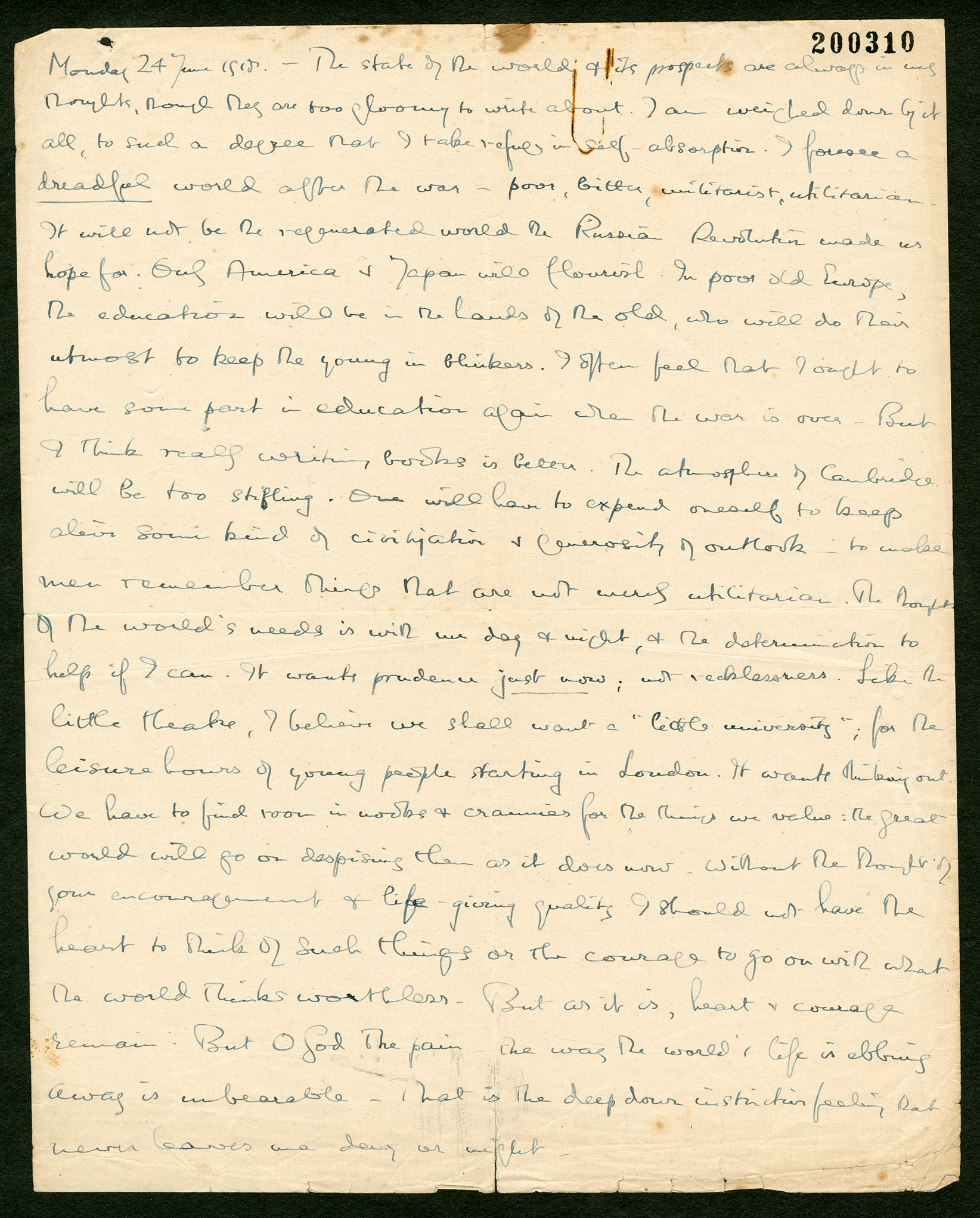

Monday 24 June 1918.

The state of the world and its prospects are always in my thoughts, though they are too gloomy to write about. I am weighed down by it all, to such a degree that I take refuge in self-absorption. I foresee a dreadful world after the war — poor, bitter, militarist, utilitarian. It will not be the regenerated world the Russian Revolution made us hope for.2 Only America and Japan will flourish. In poor old Europe, the education will be in the hands of the old, who will do their utmost to keep the young in blinkers. I often feel that I ought to have some part in education again when the war is over. But I think really writing books is better. The atmosphere of Cambridge3 will be too stifling. One will have to expend oneself to keep alive some kind of civilization and generosity of outlook — to make men remember things that are not merely utilitarian. The thought of the world’s needs is with me day and night, and the determination to help if I can. It wants prudence just now; not recklessness. Like the little theatre,4 I believe we shall want a “little university”; for the leisure hours of young people starting in London. It wants thinking out. We have to find room in nooks and crannies for the things we value: the great world will go on despising them as it does now. Without the thought of your encouragement and life-giving quality I should not have the heart to think of such things or the courage to go on with what the world thinks worthless. But as it is, heart and courage remain. But O God the pain — the way the world’s life is ebbing away is unbearable. That is the deep down instinctive feeling that never leaves me day or night.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the unsigned original in BR’s handwriting in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. The single sheet of laid paper, ruled on one side, was folded twice.

- 2

world the Russian Revolution made us hope for BR outlined his hopes for a regenerated world in “Russia Leads the Way”, The Tribunal, no. 52 (22 March 1917): 2; 23 in Papers 14. After the bloodless overthrow of the Tsarist regime in March 1917, and the ensuing calls of some Russian revolutionaries for a peace without annexations or indemnities, BR came to believe that a formula had been found not only for ending the war, but also for the radical, non-violent transformation of all belligerent states, including Britain. This optimistic phase of his political thinking peaked that summer (“A Pacifist Revolution” [50] and “Pacifism and Revolution” [51] in Papers 14), but he was soon disabused of such Utopian notions by the Allies’ grim resolve to carry on the fight at whatever cost and the British Government’s determined domestic offensive against dissenting voices such as his own.

- 3

Cambridge Where BR had been deprived of his lectureship in July 1916.

- 4

Like the little theatre Colette and her husband, Miles Malleson, were planning on founding an Experimental Theatre (BRACERS 113135).

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Experimental Theatre

Colette first mentioned that she and Miles were trying to start an Experimental Theatre in a letter of 24 June 1918 (BRACERS 113135), indicating that Miles would earn a tiny income from it. About a month later, she wrote that Elizabeth Russell had subscribed generously to the Theatre and that £700 had been raised, but hundreds still had to be found (BRACERS 113146). A few days later she wrote that Captain Stephen Gordon, a north-country lawyer working for the government, was to be the honorary treasurer, noting that he had “put most of the drive into the whole thing” (BRACERS 113147). During August Colette was happy with her involvement with the Theatre (Letter 68). John Galsworthy came to tea to discuss the project (c.14 Aug., BRACERS 113149). On 2 September she listed the members of the Theatre committee as “Desmond <MacCarthy>, Massingham, Galsworthy, and Dennis (Bradley)” (BRACERS 113155). The following day she wrote that she was learning three parts (BRACERS 113156). In her memoirs, Colette wrote about the “Experimental Little Theatre” but dated it 1919 (After Ten Years [London: Cape, 1931], pp. 129–30). An “artistic” theatre did get founded in 1920 in Hampstead, and John Galsworthy was connected to that venture, The Everyman Theatre — he was part of a reading committee which chose the works to be performed (The Times, 9 Sept. 1919, p. 8). The Everyman Theatre was under the direction of Norman MacDermott. In his book Everymania (London: Society for Theatre Research, 1975), he noted that he met Miles in the summer of 1918: they rented a store in Bloomsbury, had a cabinetmaker build sets, and put on plays with actors “bored with West-End theatres” (p. 10). It is likely that the Everyman Theatre was an out-growth of the Experimental Theatre.

Miles Malleson

Miles Malleson (1888–1969), actor and playwright, was born in Croydon, Surrey, the son of Edmund and Myrrha Malleson. He married his first wife, a fellow actor, Lady Constance Annesley (stage name, Colette O’Niel), in 1915. They had met at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts). Their marriage was an “open” one. In 1914 Miles enlisted in the City of London Fusiliers and was sent to Malta. He became ill and was discharged, unfit for further service. He became active in the No-Conscription Fellowship and wrote anti-war stage plays as well as a pamphlet, Cranks and Commonsense (1916). In the 1930s he began to write for the screen and act in films, in which he became a very well-known character actor, as well as continuing his stage career at the Old Vic in London. He married three times: his second marriage was to Joan Billson, a physician (married 1923, divorced 1940), with whom he had two children; his third wife was Tatiana Lieven, an actress (married 1946). He died in London in March 1969.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.