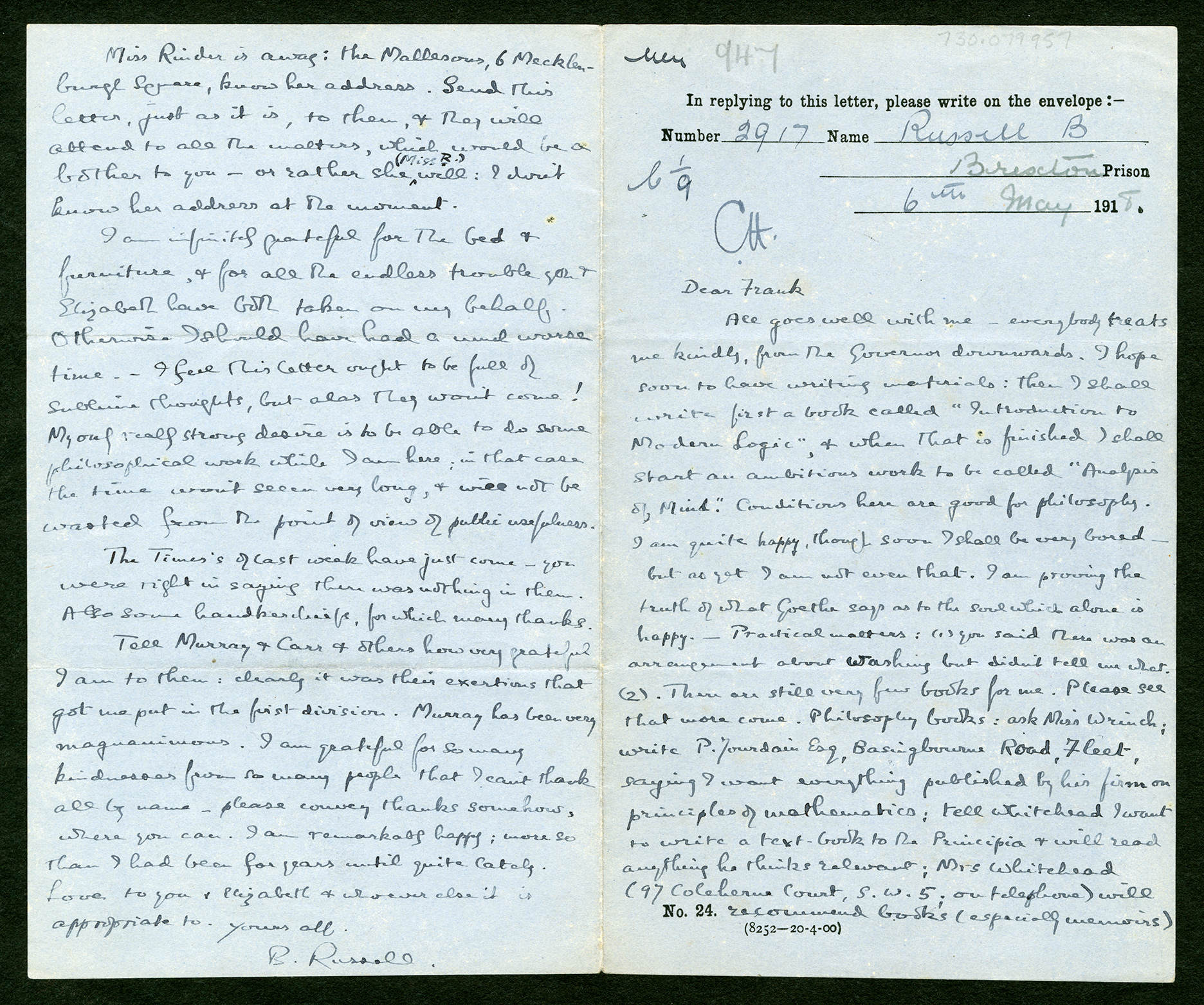

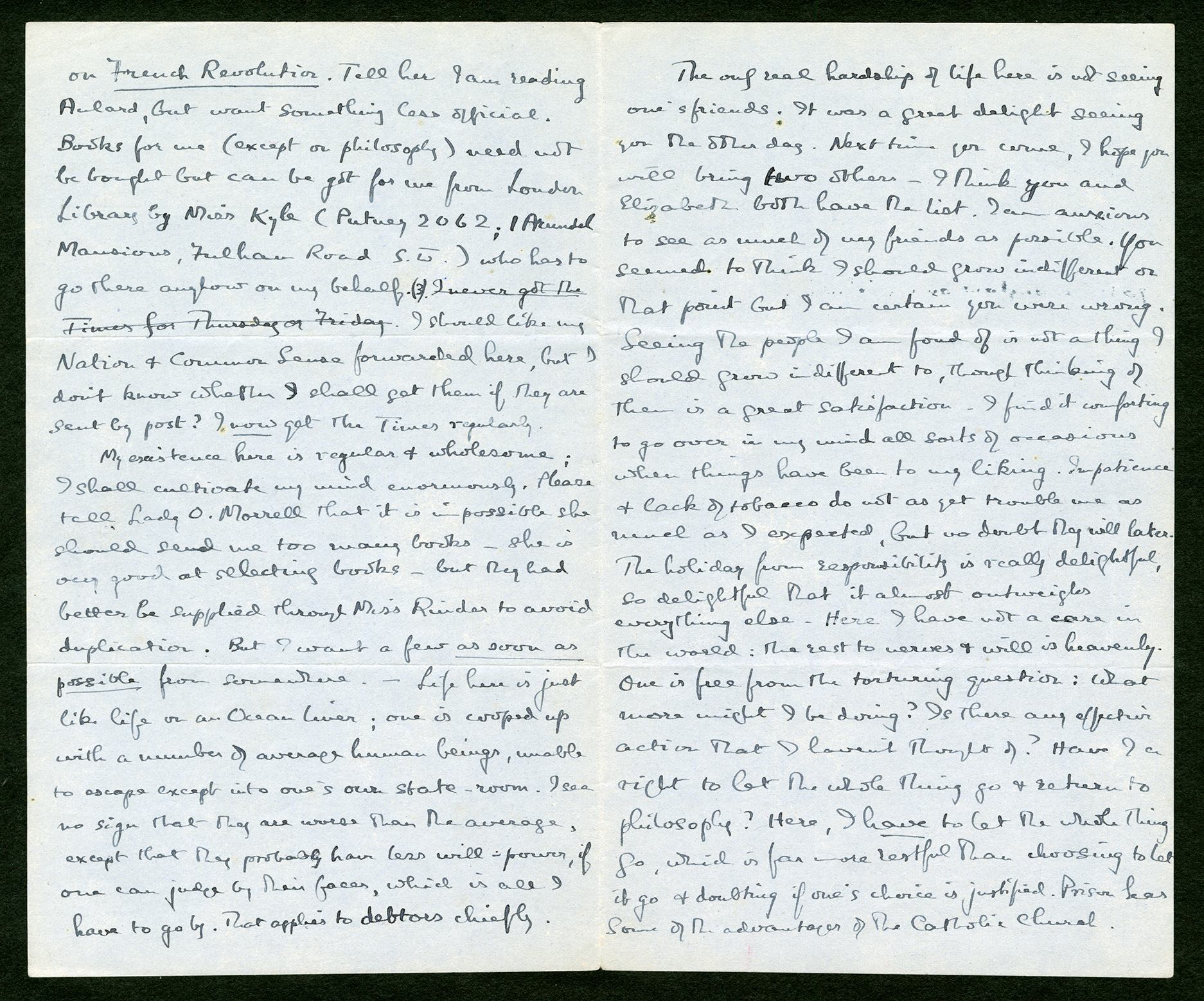

Brixton Letter 2

BR to Frank Russell

May 6, 1918

- ALS

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-2SLBR 2: #312

BRACERS 46911

<letterhead>1

Number 2917 Name Russell B

Brixton Prison

6th May 1918.

Dear Frank

All goes well with me — everybody treats me kindly, from the Governor2 downwards. I hope soon to have writing materials: then I shall write first a book called Introduction to Modern Logic,3 and when that is finished I shall start an ambitious work to be called Analysis of Mind.4 Conditions here are good for philosophy. I am quite happy, though soon I shall be very bored — but as yet I am not even that. I am proving the truth of what Goethe says as to the soul which alone is happy.5 — Practical matters: (1) you said there was an arrangement about washing6 but didn’t tell me what. (2). There are still very few books for me. Please see that more come. Philosophy books: ask Miss Wrinch; write P. Jourdain Esq, Basingbourne Road, Fleet, saying I want everything published by his firm7 on principles of mathematics; tell Whitehead I want to write a text-book to the Principia8 and will read anything he thinks relevant; Mrs Whitehead (97 Coleherne Court, S.W.5; on telephone) will recommend books (especially memoirs) on French Revolution. Tell her I am reading Aulard,9 but want something less official. Books for me (except on philosophy) need not be bought but can be got for me from London Library by Miss Kyle (Putney 2062; 1 Arundel Mansions, Fulham Road S.W.)a who has to go there anyhow on my behalf. (3).b I should like my Nation10 and Common Sense11 forwarded here, but I don’t know whether I shall get them if they are sent by post? I now get the Times regularly.

My existence here is regular and wholesome; I shall cultivate my mind enormously. Please tell Lady O. Morrell that it is impossible she should send me too many books — she is very good at selecting books — but they had better be supplied through Miss Rinder to avoid duplication. But I want a few as soon as possible from somewhere. — Life here is just like life on an Ocean liner; one is cooped up with a number of average human beings, unable to escape except into one’s own state-room. I see no sign that they are worse than the average, except that they probably have less will-power, if one can judge by their faces, which is all I have to go by. That applies to debtors chiefly.

The only real hardshipc of life here is not seeing one’s friends. It was a great delight seeing you the other day. Next time you come, I hope you will bring two others — I think you and Elizabeth both have the list.12 I am anxious to see as much of my friends as possible. You seemed to think I should grow indifferent on that point but I am certain you were wrong. Seeing the people I am fond of is not a thing I should grow indifferent to, though thinking of them is a great satisfaction. I find it comforting to go over in my mind all sorts of occasions when things have been to my liking. Impatience and lack of tobacco13 do not as yet trouble me as much as I expected, but no doubt they will later. The holiday from responsibility is really delightful, so delightful that it almost outweighs everything else. Here I have not a care in the world: the rest to nerves and will is heavenly. One is free from the torturing question: What more might I be doing?14 Is there any effective action that I haven’t thought of? Have I a right to let the whole thing go and return to philosophy?15 Here, I have to let the whole thing go, which is far more restful than choosing to let it go and doubting if one’s choice is justified. Prison has some of the advantages of the Catholic Church.

Miss Rinder is away: the Mallesons,16 6 Mecklenburgh Square, know her address. Send this letter, just as it is, to them, and they will attend to all the matters, which would be a bother to you — or rather she (Miss R.)d will: I don’t know her address at the moment.

I am infinitely grateful for the bed and furniture, and for all the endless trouble you and Elizabeth have both taken on my behalf. Otherwise I should have had a much worse time. — I feel this letter ought to be full of sublime thoughts, but alas they won’t come! My only really strong desire is to be able to do some philosophical work while I am here; in that case the time won’t seem very long, and will not be wasted from the point of view of public usefulness.

The Times’s of last week have just come — you were right in saying there was nothing in them.17 Also some handkerchiefs, for which many thanks.

Tell Murray and Carr and others how very grateful I am to them: clearly it was their exertions18 that got me put in the first division. Murray has been very magnanimous. I am grateful for so many kindnesses from so many people that I can’t thank all by name — please convey thanks somehow, where you can. I am remarkably happy; more so than I had been for years until quite lately. Love to you and Elizabeth and whoever else it is appropriate to.

Yours aff.e

B. Russell.

- 1

[document] Included in Frank Russell’s files in the Russell Archives, the letter was edited from the signed original in BR’s handwriting. On the blue correspondence form of the prison system, it consists of a single sheet folded once vertically; all four sides are filled. Particulars, such as BR’s name and number, were entered in an unknown hand. Prisoners’ correspondence was subject to the approval of the governor or his deputy. This letter has “CH” (for “Carleton Haynes”) handwritten at the top, making it an official letter. Among the several markings on the letter is a cumulative number (“947”) added in the late 1940s as BR was going through his papers (see K. Blackwell, “Doing Archival History with BRACERS”, Bertrand Russell Research Centre Newsletter, no. 2 [autumn 2003]: 3–4). Other Brixton letters are numbered similarly, as they were encountered in the same envelope or folder. The letter was published as #312 in Vol. 2 of BR’s Selected Letters.

- 2

Governor Captain Carleton Haynes.

- 3

writing materials … Introduction to Modern Logic It was not until 16 May 1918 (Letter 5) that BR was able to note “Ink, fountain pen, etc. just come”. Their arrival may be a clue to when he started writing the book, whose title soon became Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy. If so, he reported astonishing progress, reaching 20,000 words by 21 May (Letter 7) and nearly 70,000 by 27 May (Letter 9). But it may only indicate a change of writing materials. The first two chapters of the manuscript (RA Rec. Acq. 412, fos. 1–25) are in a greyish black ink. From Chapter 3 on (202 fos.), the ink is dark blue and the pen nib thinner. All, or almost all, of the last sixteen of the eighteen chapters, therefore, seem to have been written between 16 and 27 May. It was a remarkable achievement: approaching 65,000 words in eleven (or twelve) days. Allen & Unwin published the book in March 1919. It was based on a course of public lectures, “The Philosophy of Mathematics” (see BRACERS 47442) that BR gave in autumn 1917. BR embedded in the chapter on Descriptions an eloquent defiance of his situation: “It may be thought excessive to devote two chapters to one word, but to the philosophical mathematician it is a word of very great importance: like Browning’s Grammarian with the enclitic δε, I would give the doctrine of this word if I were ‘dead from the waist down’ and not merely in a prison” (p. 167). A corrected edition with variants is at https://people.umass.edu/klement/imp/imp.html.

- 4

an ambitious work … Analysis of Mind Quite how ambitious is shown by the two-page outline printed in Papers 8: App. II — and that was only of “the section dealing with cognition in a large projected work, Analysis of Mind” (Papers 8: 313). The Analysis of Mind, as it was published in June 1921, is a shadow of this massive work, preparing which was BR’s main philosophical task while in prison. The Analysis of Mind marks a major change in direction for BR’s philosophy, not only in the topics dealt with, but in his more naturalist, empiricist approach to them. Prison was a time of philosophical change for BR.

- 5

happy. “Glücklich allein ist die Seele die liebt.” (BR’s note.) (His note is on the document at BRACERS 116553.)This is Klärchen’s lyric “Freudvoll und Leidvoll” in Act III of Goethe’s play Egmont (1788), which translates as “Happy alone is the soul that loves”.

- 6

arrangement about washing Frank wrote the next day: “The Governor told me that your washing could be done near the prison, and the Warder or the caterer would make the arrangements for you” (BRACERS 46912).

- 7

firm In 1912, Jourdain was English editor of The Monist, a journal owned by Open Court, an American publisher which published mainly philosophy.

- 8

text-book to the Principia Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy might well be thought to be a “text-book to the Principia”, but it cannot have been that book which BR had in mind here: for one thing, the Introduction was already well in hand, for BR had given the public lecture series titled “The Philosophy of Mathematics” on which the book was based in autumn 1917; for another, he did not need Whitehead’s advice on reading in order to complete it. The “text-book” mentioned here referred to a different project. BR had had it in mind for some time to write a book on logic to expound and presumably defend the logic which forms the basis of Principia Mathematica and which is, as many critics have complained, too casually and informally stated in the Introduction there. Alas, it was never written.

- 9

Aulard Presumably Alphonse Aulard’s Histoire politique de la révolution française (1901).

- 10

NationThe Nation was a political and literary weekly, 1907–21, edited for its entirety by H.W. Massingham until it merged with The Athenaeum and then The New Statesman. BR regularly contributed book reviews, starting in 1907. During his time at Brixton, he published in the Nation a book review (14 in Papers 8; see mentions in Letters 4 and 102) and a letter to the editor (Letter 39).

- 11

Common SenseA radical weekly edited by F.W. Hirst, who had lately organized the raising of a £425 subscription to finance BR’s unsuccessful appeal (see Papers 14: 394). In a message sent via Gladys Rinder, H.W. Massingham hoped that BR would contact Hirst, who was “so fond of him, and so immensely admiring of him” (25 May 1918, BRACERS 79611). Surprisingly, BR never contributed to Common Sense, at any rate under his own name.

- 12

list No such primary list by BR of potential visitors is extant, and we cannot know who was on it. But certain names are missing from a secondary list of names in Letter 5 (to Frank), which lists “Extra people for Visits, in order of preference”. Conspicuously absent from the secondary list are: Frank and Elizabeth Russell, Constance Malleson, Ottoline Morrell, A.N. Whitehead, Wildon Carr, John Withers, Gladys Rinder, Clifford Allen and Dorothy Wrinch. For a list compiled from the correspondence of the period of those who did visit him in prison, or who were mentioned as possible visitors, see appendix 4 of S. Turcon’s “Like a Shattered Vase: Russell’s 1918 Prison Letters”, Russell 30 (2010): 101–25. Rinder’s letter of 9 August 1918 (BRACERS 79625) adds three names to those in appendix 4 of the article: those of Robert C. Trevelyan, and (as possibles) Ralph G. Hawtrey and T.J. Cobden-Sanderson.

- 13

tobacco BR was a lifelong pipe-smoker since the age of nineteen (BR to Max Roseblume, 22 March 1940, BRACERS 46486; BRACERS 10395 and 14343; see also L.P. Smith to BR, 3 Dec. 1891, BRACERS 80826, Auto. 1: 90; and, for his pipe tobacco, Letter 99, note 17).

- 14

What more might I be doing? Prior to his imprisonment BR had been active in advocating for the C.O.s, opposing the war, and publicizing his model for post-war social reconstruction.

- 15

right to … return to philosophy The question was hardly moot, for BR had returned to philosophy in 1917 — teaching students in mathematical Logic (Jean Nicod, Dorothy Wrinch, Victor Lenzen, Raphael Demos and possibly others), preparing the new edition of Philosophical Essays (retitled Mysticism and Logic [see note 6 in Letter 30]), offering the lecture course “The Philosophy of Mathematics” in the autumn, planning a revised or rewritten edition of The Principles of Mathematics, and preparing 1918’s course “The Philosophy of Logical Atomism”. As he wrote Jourdain on 4 September, “My interest in philosophy is reviving, and I expect before long I shall come back to it altogether” (BRACERS 77871; I. Grattan-Guinness, Dear Russell — Dear Jourdain [London: Duckworth, 1977], p. 142). N. Griffin puts the revival at (at least) the beginning of August (SLBR 2: 117).

- 16

Mallesons Constance (“Colette”) Malleson and her husband, Miles.

- 17

nothing in them This is not a comment on the quality of the journalism. Colette had arranged to send messages to him via the Personals column. Hence BR’s concern that he got his copy of The Times on time. Colette’s first message, using the code name “G.J.”, appeared on 7 May. For her text see BRACERS 96064.

- 18

their exertionsCarr, Murray and Samuel Alexander, a former president of the Aristotelian Society, had signed and circulated to academic philosophers an appeal to the Home Secretary for BR’s sentence to be served in the first division — lest his extraordinary intellectual gifts be impaired by the extremely harsh conditions of confinement in the second. In his Autobiography (2: 34) BR later acknowledged the efforts made on his behalf by the Foreign Secretary (and philosopher), Arthur Balfour, who may have discreetly influenced the magistrate’s concession of first-division status at BR’s appeal hearing (see also R. Gathorne-Hardy, ed., Ottoline at Garsington: Memoirs of Lady Ottoline Morrell, 1915–1918 [London: Faber and Faber, 1974], p. 251).

Textual Notes

- a

Fulham Road S.W. BR wrote the final letter of her postal code with a macron over the W (“W̅”), as he sometimes did to specify a capital W in logic and on envelopes. There are more examples in the originals of Letters 4 and 6. The “character” resurfaced in BR’s “Reply to Criticisms” in The Philosophy of Bertrand Russell, ed. P.A. Schilpp (Evanston and Chicago: Northwestern U., 1944), pp. 715–16), and was reprinted as such in Papers 11: 44.

- b

(3). BR here deleted “I never got the Times for Thursday or Friday”.

- c

hardship He expected it (delete this test note).

- d

(Miss R.) Inserted.

- e

Yours aff. Short for “Yours affectionately”. An informal way of closing a letter.

A.N. Whitehead

Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947), Cambridge-educated mathematician and philosopher. From 1884 to 1910 he was a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, and lecturer in mathematics there; from 1911 to 1924 he taught in London, first at University College and then at the Imperial College of Science and Technology; in 1924 he took up a professorship in philosophy at Harvard and spent the rest of his life in America. BR took mathematics courses with him as an undergraduate, which led to a lifelong friendship. Whitehead’s first major work was A Treatise on Universal Algebra (1898), which treated selected mathematical theories as “systems of symbolic reasoning”. Like BR’s The Principles of Mathematics (1903), it was intended as the first of two volumes; but in 1900 he and BR discovered Giuseppe Peano’s work in symbolic logic, and each decided to set aside his projected second volume to work together on a more comprehensive treatment of mathematics using Peano’s methods. The result was the three volumes of Principia Mathematica (1910–13), which occupied the pair for over a decade. After Principia was published, Whitehead’s interests, like BR’s, turned to the empirical sciences and, finally, after his move to America, to pure metaphysics. See Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: the Man and His Work, 2 vols. (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins U. P., 1985–90).

Annotations by BR

In the late 1940s, when BR was going through his archives, and in the 1950s when he was revising his Autobiography, he would occasionally annotate letters. He did this to sixteen of the Brixton letters. Links to them are gathered here for convenient access to these new texts. In the annotations to the letters they are always followed by “(BR’s note.)”

Letter 2, note 5 happy.

5, note 6 congratulations to G.J.

9, note 28 bit of Girondin history.

12, note 6 friend.

15, note 2 (the letter in general).

20, note 7 G.J.

31, note 3 Dr’s treatment.

40, notes 9, 10 Ld. G.L.G, Lady B’s.

44, note 14 S.S.

48, note 48 Mother Julian’s Bird.

57, notes 13, 16 Ld. Granville’s to Ly. B., bless that Dr. … seat of intellect.

70, note 15 Mrs Scott.

73, note 12 E.S.P. Haynes.

76, note 4 Cave.

85, note 2 Marsh on Rupert.

102, notes 23, 28 Woolley, K. Lonsdale.

General Annotations

Brett note from Auto. 2: 93

Cousens note from Auto. 2: 71

Kyle note with her letters to BR

Rinder note from Auto. 2: 88n.

Silcox note on BRACERS 80365

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Clifford Allen

(Reginald) Clifford Allen (1889–1939; Baron Allen of Hurtwood, 1932) was a socialist politician and publicist who joined the Cambridge University Fabian Society while studying at Peterhouse College (1908–11). After graduating he became active in the Independent Labour Party in London and helped establish a short-lived labour newspaper, the Daily Citizen. During the war Allen was an inspiring and effective leader of the C.O. movement as chairman of the No-Conscription Fellowship, which he co-founded with Fenner Brockway in November 1914. Court-martialled and imprisoned three times after his claim for absolute exemption from war service was rejected, Allen became desperately ill during his last spell of incarceration. He was finally released from the second division of Winchester Prison on health grounds in December 1917, but not before contracting the tuberculosis with which he was finally diagnosed in September 1918. He was dogged by ill health for the rest of his life. BR had enormous affection and admiration for Allen (e.g., 68 in Papers 13, 46 in Papers 14), a trusted wartime political associate. From February 1919 until March 1920 he even shared Allen’s Battersea apartment. A close friendship was soured, however, by Allen’s rejection of BR’s unforgiving critique of the Bolshevik regime, which both men witnessed at first hand with the British Labour Delegation to Russia in May 1920 (see Papers 15: 507). Yet Allen was far from revolutionary himself and did not even identify with the left wing of the ILP (which he chaired in the early 1920s). He was elevated to the peerage as a supporter of Ramsay MacDonald’s National Government, an administration despised by virtually the entire labour movement. Although Allen’s old intimacy with BR was never restored after the Russia trip, any lingering estrangement did not inhibit him from enrolling his daughter, Joan Colette (“Polly”) at the Russells’ Beacon Hill School.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.

Dorothy Wrinch

Dorothy Maud Wrinch (1894–1976), mathematician, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. She studied mathematics and philosophy at Girton College, Cambridge, and came under BR’s influence in her second year when she took his course on mathematical logic. She taught mathematics at University College, London, 1918–21, and then at Oxford, 1922–30. Her first publications were in mathematical logic and philosophy, and during the 1920s she wrote on the philosophy of science. But in the 1930s her interests turned to mathematical biology and crystallography, and in 1935 she moved to the United States on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship and remained there for the rest of her life. Unfortunately, as a biologist she is best known for a long and stubborn controversy with Linus Pauling about the structure of proteins in which he was right and she was wrong. See Marjorie Senechal, I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science (New York: Oxford U. P., 2013). Chapter 7 is devoted to Wrinch’s interactions with BR in Brixton.

Elizabeth Russell

Elizabeth Russell, born Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941), was a novelist who in 1891 married Graf von Arnim-Schlagenthin. She became known as “Elizabeth”, the name she used in publishing Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898), and she remained widely known as Elizabeth von Arnim, although the Library of Congress catalogues her as Mary Annette (Beauchamp), Countess von Arnim. She was a widow when she married BR’s brother, Frank, on 11 February 1916. The marriage was quickly in difficulty; she left it for good in March 1919, but they were never divorced and she remained Countess Russell (becoming Dowager Countess after Frank’s death in 1931).

Eva Kyle

Eva Kyle ran a typing service. She did work for the No-Conscription Fellowship and took BR’s dictation of his book, Roads to Freedom, in the early months of 1918. He annotated a letter from her: “She was an admirable typist but very fat. We all agreed that she was worth her weight in gold, though that was saying a great deal.” Her prison letter to him is clever and amusing. She typed his major prison writings and apologized for the amount of the invoice when he emerged.

Evelyn Whitehead

Evelyn (Willoughby-Wade) Whitehead (1865–1961). Educated in a French convent, she married Alfred North Whitehead in 1891. Her suffering, during an apparent angina attack, inspired BR’s profound sympathy and occasioned a storied episode which he described as a “mystic illumination” (Auto. 1: 146). Through her he supported the Whitehead family finances during the writing of Principia Mathematica. During the early stages of his affair with Ottoline Morrell, she was BR’s confidante. They maintained their mutual affection during the war, despite the loss of her airman son, Eric. BR last visited Evelyn in 1950 in Cambridge, Mass., when he found her in very poor health.

First Division

As part of a major reform of the English penal system, the Prison Act (1898) had created three distinct categories of confinement for offenders sentenced to two years or less (without hard labour) in a “local” prison. (A separate tripartite system of classification applied to prisoners serving longer terms of penal servitude in Britain’s “convict” prisons.) For less serious crimes, the courts were to consider the “nature of the offence” and the “antecedents” of the guilty party before deciding in which division the sentence would be served. But in practice such direction was rarely given, and the overwhelming majority of offenders was therefore assigned third-division status by default and automatically subjected to the harshest (local) prison discipline (see Victor Bailey, “English Prisons, Penal Culture, and the Abatement of Imprisonment, 1895–1922”, Journal of British Studies 36 [1997]: 294). Yet prisoners in the second division, to which BR was originally sentenced, were subject to many of the same rigours and rules as those in the third. Debtors, of whom there were more than 5,000 in local prisons in 1920, constituted a special class of inmate, whose less punitive conditions of confinement were stipulated in law rather than left to the courts’ discretion.

The exceptional nature of the first-division classification that BR obtained from the unsuccessful appeal of his conviction should not be underestimated. The tiny minority of first-division inmates was exempt from performing prison work, eating prison food and wearing prison clothes. They could send and receive a letter and see visitors once a fortnight (more frequently than other inmates could do), furnish their cells, order food from outside, and hire another prisoner as a servant. As BR’s dealings with the Brixton and Home Office authorities illustrate, prison officials determined the nature and scope of these and other privileges (for some of which payment was required). “The first division offenders are the aristocrats of the prison world”, concluded the detailed inquiry of two prison reformers who had been incarcerated as conscientious objectors: “The rules affecting them have a class flavour … and are evidently intended to apply to persons of some means” (Stephen Hobhouse and A. Fenner Brockway, eds., English Prisons To-day [London: Longmans, Green, 1922], p. 221). BR’s brother described his experience in the first division at Holloway prison, where he spent three months for bigamy in 1901, in My Life and Adventures (London: Cassell, 1923), pp. 286–90. Frank Russell paid for his “lodgings”, catered meals were served by “magnificent attendants in the King’s uniform”, and visitors came three times a week. In addition, the governor spent a half-hour in conversation with him daily. At this time there were seven first-class misdemeanants, who exercised (or sat about) by themselves. Frank concluded that he had “a fairly happy time”, and “I more or less ran the prison as St. Paul did after they had got used to him.” BR’s privileges were not quite so splendid as Frank’s, but he too secured a variety of special entitlements (see Letter 5).

French Revolution Reading

In Letter 2 (6 May 1918) BR instructed his brother to ask Evelyn Whitehead to “recommend books (especially memoirs) on French Revolution”, and reported that he was already reading “Aulard” — presumably Alphonse Aulard’s Histoire politique de la révolution française (Paris: A. Colin, 1901). In a message to Ottoline sent via Frank ten days later (Letter 5), BR hinted that he was especially interested in the period after August 1792, which he felt was “very like the present day”. On 27 May (Letter 9), he conveyed to Frank his disappointment that Evelyn had not yet procured for him any memoirs of the revolutionary era, and that Eva Kyle had only furnished him with The Principal Speeches of the Statesmen and Orators of the French Revolution, 1789–1795, ed. H. Morse Stephens, 2 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1892). This was “not the sort of book I want, BR complained”, but “an old stager history which I have read before” (in Feb. 1902: “What Shall I Read?”, Papers 1: 365). Fortunately, some of the desired literature reached him shortly afterwards, including The Private Memoirs of Madame Roland, ed. Edward Gilpin Johnson (London: Grant Richards, 1901: see Letter 12) — or else a different edition of the doomed Girondin’s prison writings — and the Memoirs of the Comtesse de Boigne, ed. Charles Nicoullaud, 3 vols. (London: Heinemann, 1907: see Letter 15). In Letter 48, BR told Ottoline that he was “absorbed in a 3-volume Mémoire” of the Comte de Mirabeau. The edition has not been identified, but quotations attributed to the same aristocratic revolutionary in Letter 44 appear in Lettres d’amour de Mirabeau, précédées d’une étude sur Mirabeau par Mario Proth (Paris: Garnier Frères, 1874). Some weeks after writing Letter 11 to Colette as one purportedly from Mirabeau to Sophie de Monier (sic), BR actually read the lovers’ prison correspondence, possibly in Benjamin Gastineau’s edition: Les Amours de Mirabeau et de Sophie de Monnier, suivis des lettres choisies de Mirabeau à Sophie, de lettres inédites de Sophie, et du testament de Mirabeau par Jules Janin (Paris: Chez tous les libraires, 1865). BR’s reading on the French Revolution also included letters from Études révolutionnaires, ed. James Guillaume, 2 vols. (Paris: Stock, 1908–09), the collection he misleadingly cited as the source for two other illicit communications to Colette (Letters 8 and 10). Also of relevance (Letter 57) were Napoleon Bonaparte’s letters to his first wife, Joséphine de Beauharnais, which BR may have read in this well-known English translation edited by Henry Foljambe Hall: Letters to Josephine, 1796–1812 (London: J.M. Dent, 1901). Finally, BR obtained a hostile, cross-channel perspective on the French Revolution and Napoleon from Lord Granville’s Private Correspondence, 1781–1821, ed. Castalia, Countess Granville, 2 vols. (London: J. Murray, 1917: see Letters 40, 41 and 44). Commenting towards the end of his sentence on the mental freedom that he had been able to preserve in Brixton, BR wrote about living “in the French Revolution” among other times and places (Letter 90). His immersion in this tumultuous era may have been deeper still if he perused other works not mentioned in his Brixton letters — which he may well have done. Yet BR’s examination of the French Revolution was not at all programmatic (as intimated perhaps by his preference for personal accounts (diaries and letters in addition to memoirs) — unlike much of his philosophical prison reading. Although his political writings are scattered with allusions to the French Revolution (in which he was interested long before Brixton), BR never produced a major study of it. Just over a year after his imprisonment, however, he did publish a scathing and even profound review of reactionary author Nesta H. Webster’s history of the French Revolution, which certainly drew on his reservoir of knowledge about the period (“The Seamy Side of Revolution”, The Athenaeum, no. 4,665 [26 Sept. 1919]: 943–4; Papers 15: 19). While imprisoned briefly in Brixton for a second time, in September 1961, Russell returned to the era of the French Revolution and Napoleon, “enjoying … immensely” (Letter 105) this biography of Mme. de Staël: J. Christopher Herold, Mistress to an Age: a Life of Madame de Staël (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1959; Russell’s library).

Gilbert Murray

Gilbert Murray (1866–1957), distinguished classical scholar and dedicated liberal internationalist. He was Regius Professor of Greek at Oxford, 1908–36, and chair of the League of Nations Union, 1923–36. He and BR enjoyed a long and close friendship that was ruptured temporarily by bitter disagreement over the First World War. After Murray published The Foreign Policy of Sir Edward Grey, 1906–1915, in defence of Britain’s pre-war diplomacy, BR responded with a detailed critique, The Policy of the Entente, 1904–1914: a Reply to Professor Gilbert Murray (37 in Papers 13). Yet Murray still took the lead in campaigning to get BR’s sentence reassigned from the second to the first division and (later) in leading an appeal for professional and financial backing of an academic appointment for BR upon his release (the “fellowship plan”, which looms large in his prison correspondence). BR was still thankful for Murray’s exertions some 40 years later. See his portrait of Murray, “A Fifty-Six Year Friendship”, in Murray, An Unfinished Autobiography with Contributions by His Friends, ed. Jean Smith and Arnold Toynbee (London: Allen & Unwin, 1960).

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Governor of Brixton Prison / Carleton Haynes

Captain Carleton Haynes (1858–1945), the Governor of Brixton Prison in 1918, was a retired army officer and a cousin of BR’s acquaintance, the radical lawyer and author E.S.P. Haynes. In March 1919 BR sent Haynes, in jest, a copy (now in the Russell Archives) of his newly published Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy — so that the governor’s collection of works written by inmates while under his charge would “not ... be incomplete” (BRACERS 123167).

H. Wildon Carr

Herbert Wildon Carr (1857–1931), Professor of Philosophy at King’s College, London, from 1918 and Visiting Professor at the University of Southern California from 1925. Carr came to philosophy late in life after a lucrative career as a stockbroker. His philosophy was an idiosyncratic amalgam of Bergsonian vitalism and Leibnizian monadology, which, he thought, was supported by modern biology and the theory of relativity. He wrote books on Bergson and Leibniz at opposite ends of his philosophical career and a book on relativity in the middle. His philosophy would have made him an unlikely ally of BR’s, but it was Carr who organized BR’s two courses of public lectures, on philosophy of mathematics and the philosophy of logical atomism, which brought BR back to philosophy and improved his finances in 1917–18. Carr had great administrative talents, which he employed also on behalf of the Aristotelian Society during his long association with it. He was its president in 1916–18 and continued to edit its Proceedings until 1929.

H.W. Massingham

H.W. Massingham (1860–1924), radical journalist and founding editor in 1907 of The Nation, a publication which superseded The Speaker and soon became Britain’s foremost Liberal weekly. Almost immediately the editor of the new periodical started to host a weekly luncheon (usually at the National Liberal Club), which became a vital forum for the exchange of “New Liberal” ideas and strategies between like-minded politicians, publicists and intellectuals (see Alfred F. Havighurst, Radical Journalist: H.W. Massingham, 1860–1924 [Cambridge: U. P., 1974], pp. 152–3). On 4 August 1914, BR attended a particularly significant Nation lunch, at which Massingham appeared still to be in favour of British neutrality (see Papers 13: 6) — which had actually ended at the stroke of midnight. By the next day, however, Massingham (like many Radical critics of Britain’s pre-war diplomacy) had come to accept the case for military intervention, a position he maintained (not without misgivings) for the next two years. Massingham was still at the helm of the Nation when it merged with the more literary-minded Athenaeum in 1921; he finally relinquished editorial control two years later. In 1918 he served on Miles and Constance Malleson’s Experimental Theatre Committee.

J.J. Withers

John James Withers (1863–1939; knighted 1929) was senior partner in the prominent City law firm that bore his name and was located near the legal district of the Temple. Specialists in family law (although clearly not to the exclusion of other services), Withers & Co. acted for both BR and his brother for many years. In 1926 Withers was elected unopposed as Conservative M.P. for Cambridge University and held the seat for the remainder of his life.

Miles Malleson

Miles Malleson (1888–1969), actor and playwright, was born in Croydon, Surrey, the son of Edmund and Myrrha Malleson. He married his first wife, a fellow actor, Lady Constance Annesley (stage name, Colette O’Niel), in 1915. They had met at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts). Their marriage was an “open” one. In 1914 Miles enlisted in the City of London Fusiliers and was sent to Malta. He became ill and was discharged, unfit for further service. He became active in the No-Conscription Fellowship and wrote anti-war stage plays as well as a pamphlet, Cranks and Commonsense (1916). In the 1930s he began to write for the screen and act in films, in which he became a very well-known character actor, as well as continuing his stage career at the Old Vic in London. He married three times: his second marriage was to Joan Billson, a physician (married 1923, divorced 1940), with whom he had two children; his third wife was Tatiana Lieven, an actress (married 1946). He died in London in March 1969.

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

Philip Jourdain

Philip Edward Bertrand Jourdain (1879–1919), Cambridge-educated logician and historian of mathematics and logic. As a student at Cambridge he took BR’s course on mathematical logic in 1901–02 and subsequently wrote many articles on mathematical logic, set theory, and the foundations of mathematics, among a number of other topics. His extraordinary productivity was achieved despite the ravages of Friedreich’s ataxia, a form of progressive paralysis that killed him in 1919. His extensive correspondence with BR was published (with commentary) in I. Grattan-Guinness, Dear Russell — Dear Jourdain (London: Duckworth, 1977).

Principia Mathematica

Principia Mathematica, the monumental, three-volume work coauthored with Alfred North Whitehead and published in 1910–13, was the culmination of BR’s work on the foundations of mathematics. Conceived around 1901 as a replacement for the projected second volumes of BR’s Principles of Mathematics (1903) and of Whitehead’s Universal Algebra (1898), PM was intended to show how classical mathematics could be derived from purely logical principles. For a large swath of arithmetic this was done by actually producing the derivations. A fourth volume on geometry, to be written by Whitehead alone, was never finished. In 1925–27 BR, on his own, produced a second edition, adding a long introduction, three appendices and a list of definitions to the first volume and corrections to all three. (See B. Linsky, The Evolution of Principia Mathematica [Cambridge U. P., 2011].) In this edition, under the influence of Wittgenstein, he attempted to extensionalize the underlying intensional logic of the first edition.

Samuel Alexander

The Australian-born British philosopher Samuel Alexander (1859–1938) was originally an Hegelian whose outlook gradually shifted towards realism. He tutored at Lincoln College, Oxford, for more than a decade before accepting in 1893 a professorship at the University of Manchester, where he remained for the rest of his career. A former President of the Aristotelian Society (1908–11), Alexander joined Gilbert Murray and H. Wildon Carr in urging academic philosophers to endorse their appeal to the Home Secretary for BR to be assigned the status of a first-division prisoner (see Papers 14: 395).

The Nation

A political and literary weekly, 1907–21, edited for its entirety by H.W. Massingham before it merged with The Athenaeum and then The New Statesman. BR regularly contributed book reviews, starting in 1907. During his time at Brixton, he published there a book review (14 in Papers 8; mentioned in Letters 4 and 102) and a letter to the editor (Letter 39). In August 1914 The Nation hastily abandoned its longstanding support for British neutrality, rejecting an impassioned defence of this position written by BR on the day that Britain declared war (1 in Papers 13). For the next two years the publication gave its editorial backing (albeit with mounting reservations) to the quest for a decisive Allied victory. At the same time, it consistently upheld civil liberties against the encroachments of the wartime state, and by early 1917 had started calling for a negotiated peace as well. The Nation had recovered its dissenting credentials, but for allegedly “defeatist” coverage of the war was hit with an export embargo imposed in March 1917 by Defence of the Realm Regulation 24B.

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).