Brixton Letter 19

BR to Ottoline Morrell

June 16, 1918

- ALS

- Texas

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-19

BRACERS 18678

<Brixton Prison>1

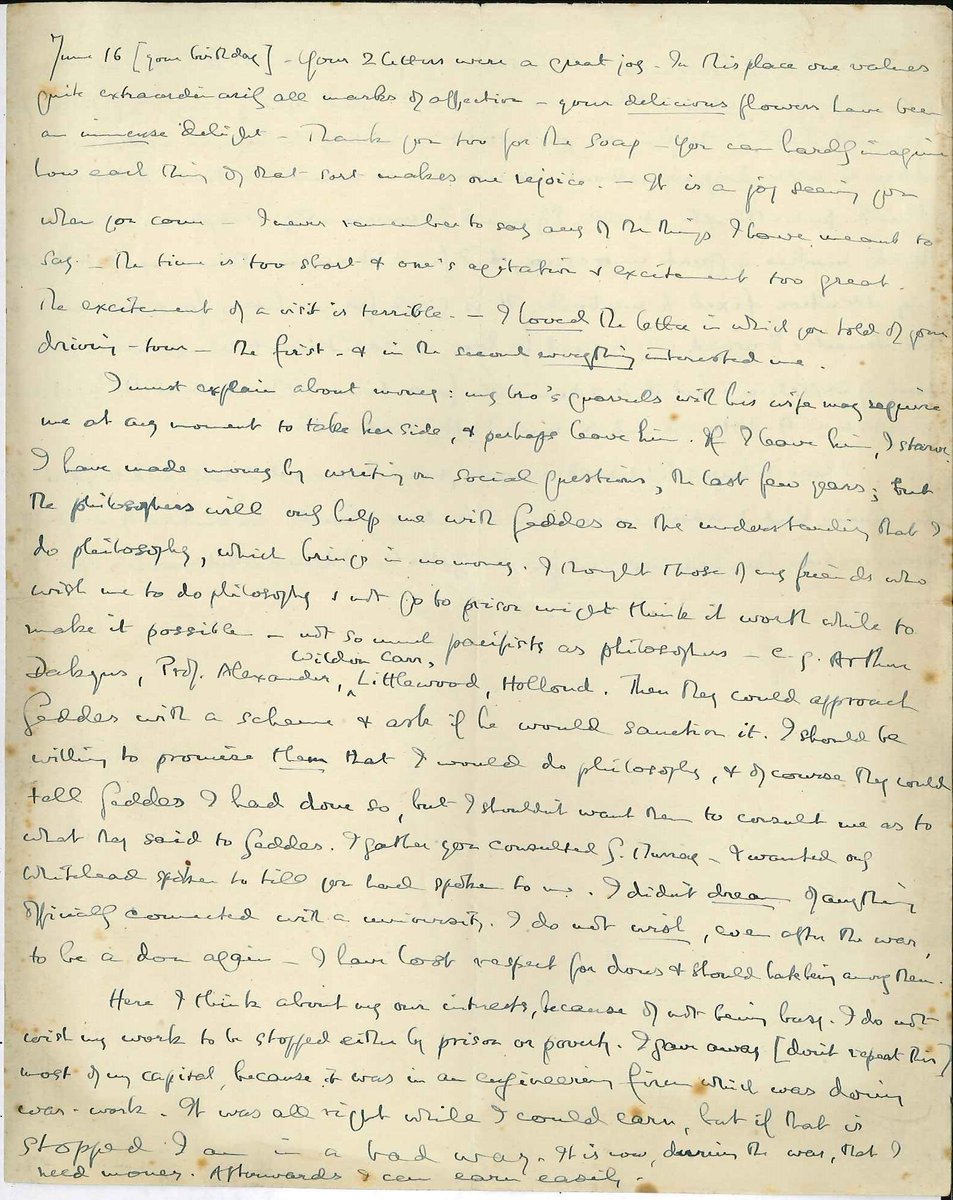

June 16 [your birthday].

Your 2 letters2 were a great joy. In this place one values quite extraordinarily all marks of affection — your delicious flowers have been an immense delight. Thank you too for the soap. You can hardly imagine how each thing of that sort makes one rejoice. — It is a joy seeing you when you come. I never remember to say any of the things I have meant to say — the time is too short and one’s agitation and excitement too great. The excitement of a visit is terrible. — I loved the letter in which you told of your driving-tour3 — the first — and the second everything interested me.

I must explain about money: my brother’s quarrels with his wife4 may require me at any moment to take her side, and perhaps leave him. If I leave him, I starve. I have made money by writing on social questions,5 the last few years; but the philosophers will only help me with Geddes on the understanding that I do philosophy, which brings in no money. I thought those of my friends who wish me to do philosophy and not go to prison might think it worth while to make it possible — not so much pacifists as philosophers — e.g. Arthur Dakyns, Prof. Alexander, Wildon Carr,a Littlewood, Hollond. Then they could approach Geddes with a scheme and ask if he would sanction it. I should be willing to promise them that I would do philosophy, and of course they could tell Geddes I had done so, but I shouldn’t want them to consult me as to what they said to Geddes. I gather you consulted G. Murray. I wanted only Whitehead spoken to till you had spoken to me. I didn’t dream of anything officially connected with a university. I do not wish, even after the war, to be a don again — I have lost respect for dons and should hate being among them.

Here I think about my own interests, because of not being busy. I do not wish my work to be stopped either by prison or poverty. I gave away [don’t repeat this] most of my capital, because it was in an engineering firm6 which was doing war-work. It was all right while I could earn, but if that is stopped I am in a bad way. It is now, during the war, that I need money. Afterwards I can earn easily.

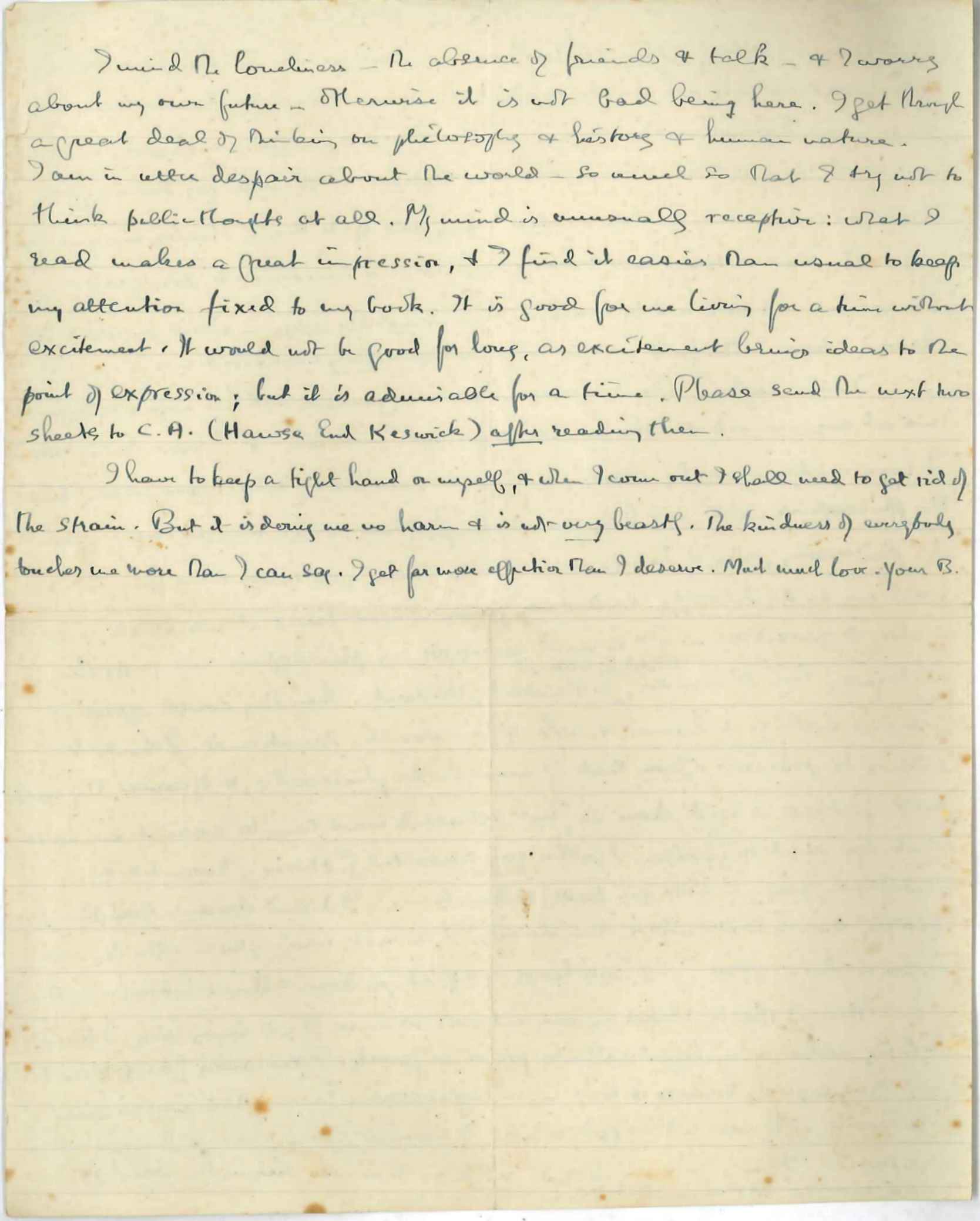

I mind the loneliness — the absence of friends and talk — and I worry about my own future — otherwise it is not bad being here. I get through a great deal of thinking on philosophy and history and human nature. I am in utter despair about the world — so much so that I try not to think public thoughts at all. My mind is unusually receptive: what I read makes a great impression, and I find it easier than usual to keep my attention fixed to my book. It is good for me living for a time without excitement. It would not be good for long, as excitement brings ideas to the point of expression; but it is admirable for a time. Please send the next two sheets to C.A. (Hawse End Keswick)7 after reading them.8

I have to keep a tight hand on myself, and when I come out I shall need to get rid of the strain. But it is doing me no harm and is not very beastly. The kindness of everybody touches me more than I can say. I get far more affection than I deserve. Much more love.

Your

B.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from a digital scan of BR’s initialled, handwritten, single-sheet letter in the Ottoline Morrell papers, Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin.

- 2

Your 2 letters BR numbered the letters he received in prison from Ottoline. No. I was written between 28 and 30 May 1918 (BRACERS 114745), and no. II was dated 1 June (BRACERS 114746). Both were smuggled into Brixton, the first by Ottoline concealing it in a small bunch of flowers (see R. Gathorne-Hardy, ed., Ottoline at Garsington: Memoirs of Lady Ottoline Morrell, 1915–1918 [London: Faber and Faber, 1974], p. 251). But BR could only have been referring here to one of these letters, for the only other mention by Ottoline of her driving-tour with Philip is in a message that Gladys Rinder placed in her letter to BR dated 25 May 1918 (BRACERS 79611).

- 3

your driving-tour See note 8 to Letter 12.

- 4

my brother’s quarrels with his wife BR’s brother, Frank, was married to the novelist “Elizabeth”. The couple had married in 1916 and never got along. Frank was bullying, prone to tantrums, and in 1918 adulterous. Elizabeth’s biographer described Elizabeth as appeasing him (Karen Usborne, ‘Elizabeth’: the Author of Elizabeth and Her German Garden (London: Bodley Head, 1986), pp. 190–5. Elizabeth’s daughter described her mother’s demeanour as “martyrdom” (Leslie de Charms, Elizabeth of the German Garden (London: Heinemann, 1958), p. 178.

- 5

writing on social questions 1916 was the turning-point in BR’s authorial career when he realized he could earn a living from his pen. That year he gave two series of public lectures, “Principles of Social Reconstruction” in London, and “The World as It Can Be Made” in various cities outside London. There were ticket receipts, at least from the first series, and then there were books, Principles of Social Reconstruction (1916; Why Men Fight in the US in 1917) and Political Ideals (1917, US only). Several chapters from each series were published in non-academic periodicals. In addition, he published other articles in periodicals that paid him fees. (See K. Blackwell and H. Ruja, A Bibliography of Bertrand Russell [London and New York: Routledge, 1994].)

- 6

I gave away … in an engineering firm BR had transferred £3,000 of debentures in this company (Plenty & Son Ltd. of Newbury) to his friend T.S. Eliot, who was then employed as a schoolteacher in High Wycombe but still struggling financially. More crucially, BR felt obliged on pacifist grounds to decline the income generated by these securities, which Eliot eventually returned to him in 1927 (BRACERS 76480). For more detail, see Eliot’s letters to BR of 16 May and 5 October 1927 (The Letters of T.S. Eliot, Vol. 3: 1926–1927, ed. Valerie Eliot and John Haffenden [New Haven: Yale U. P., 2012]).

- 7

Hawse End Keswick Where Catherine Marshall’s parents lived in the Lake District, in the former county of Westmorland (now in Cumbria). Allen and she were travelling together as a couple as he continued in his efforts to recuperate after being released from prison on health grounds in December 1917.

- 8

next two sheets … after reading them I.e., Letter 18.

Textual Notes

- a

Wildon Carr Inserted.

A.N. Whitehead

Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947), Cambridge-educated mathematician and philosopher. From 1884 to 1910 he was a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, and lecturer in mathematics there; from 1911 to 1924 he taught in London, first at University College and then at the Imperial College of Science and Technology; in 1924 he took up a professorship in philosophy at Harvard and spent the rest of his life in America. BR took mathematics courses with him as an undergraduate, which led to a lifelong friendship. Whitehead’s first major work was A Treatise on Universal Algebra (1898), which treated selected mathematical theories as “systems of symbolic reasoning”. Like BR’s The Principles of Mathematics (1903), it was intended as the first of two volumes; but in 1900 he and BR discovered Giuseppe Peano’s work in symbolic logic, and each decided to set aside his projected second volume to work together on a more comprehensive treatment of mathematics using Peano’s methods. The result was the three volumes of Principia Mathematica (1910–13), which occupied the pair for over a decade. After Principia was published, Whitehead’s interests, like BR’s, turned to the empirical sciences and, finally, after his move to America, to pure metaphysics. See Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: the Man and His Work, 2 vols. (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins U. P., 1985–90).

Arthur Dakyns

Arthur Lindsay Dakyns (1883–1941), a barrister, had been befriended by BR when Dakyns was an Oxford undergraduate and the Russells were living at Bagley Wood. BR once described Dakyns to Gilbert Murray as “a disciple” (16 May 1905, BRACERS 79178) and wrote warmly of him to Lucy Donnelly as “the only person up here (except the Murrays) that I feel as a real friend” (1 Jan. 1906; Auto. 1: 181). During the First World War Dakyns enlisted in the Royal Army Medical Corps and served in France. BR had become acquainted with the H. Graham Dakyns family, who resided in Haslemere, Surrey, after he and Alys moved to nearby Fernhurst in 1896. He corresponded with both father and son.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Clifford Allen

(Reginald) Clifford Allen (1889–1939; Baron Allen of Hurtwood, 1932) was a socialist politician and publicist who joined the Cambridge University Fabian Society while studying at Peterhouse College (1908–11). After graduating he became active in the Independent Labour Party in London and helped establish a short-lived labour newspaper, the Daily Citizen. During the war Allen was an inspiring and effective leader of the C.O. movement as chairman of the No-Conscription Fellowship, which he co-founded with Fenner Brockway in November 1914. Court-martialled and imprisoned three times after his claim for absolute exemption from war service was rejected, Allen became desperately ill during his last spell of incarceration. He was finally released from the second division of Winchester Prison on health grounds in December 1917, but not before contracting the tuberculosis with which he was finally diagnosed in September 1918. He was dogged by ill health for the rest of his life. BR had enormous affection and admiration for Allen (e.g., 68 in Papers 13, 46 in Papers 14), a trusted wartime political associate. From February 1919 until March 1920 he even shared Allen’s Battersea apartment. A close friendship was soured, however, by Allen’s rejection of BR’s unforgiving critique of the Bolshevik regime, which both men witnessed at first hand with the British Labour Delegation to Russia in May 1920 (see Papers 15: 507). Yet Allen was far from revolutionary himself and did not even identify with the left wing of the ILP (which he chaired in the early 1920s). He was elevated to the peerage as a supporter of Ramsay MacDonald’s National Government, an administration despised by virtually the entire labour movement. Although Allen’s old intimacy with BR was never restored after the Russia trip, any lingering estrangement did not inhibit him from enrolling his daughter, Joan Colette (“Polly”) at the Russells’ Beacon Hill School.

Elizabeth Russell

Elizabeth Russell, born Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941), was a novelist who in 1891 married Graf von Arnim-Schlagenthin. She became known as “Elizabeth”, the name she used in publishing Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898), and she remained widely known as Elizabeth von Arnim, although the Library of Congress catalogues her as Mary Annette (Beauchamp), Countess von Arnim. She was a widow when she married BR’s brother, Frank, on 11 February 1916. The marriage was quickly in difficulty; she left it for good in March 1919, but they were never divorced and she remained Countess Russell (becoming Dowager Countess after Frank’s death in 1931).

Fellowship Plan

Since the upper-age limit for compulsory military service had been increased to 50 in April 1918, BR was faced with the unnerving prospect of being conscripted after his release from Brixton. Early in his imprisonment he was already wondering about his “position when I emerge from here” (Letter 9). While his conviction was still under appeal, he had broached with Clifford Allen and Gilbert Murray the possibility of avoiding military service, not by asserting his conscientious objection to it, but by obtaining accreditation of his philosophical research as work of national importance (see note to Letter 24). The Pelham Committee, set up by the Board of Trade in March 1916, was responsible for the designation of essential occupations and recommending to the local tribunals, who adjudicated claims for exemption from military service, that C.O.s be considered for such positions. BR reasoned to Murray on 2 April that a dispensation to practise philosophy (as opposed to working outside his profession), would enable to him to “avoid prison without compromise” — i.e., of his political and moral opposition to conscription (BRACERS 52367). Although BR intended to withdraw from political work, he told Murray two days later, he would not promise to abstain from peace campaigning (BRACERS 52369). It should be noted that C.O.s who accepted alternative service in special Home Office camps were expressly prohibited from engaging in pacifist activities (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 231).

BR was far from sanguine about the prospect of success before a local tribunal. But he came to think (by early June) that his chances would be improved if his academic supporters interceded directly with the Minister of National Service, Sir Auckland Geddes. In addition, he calculated that such entreaties would be more effective if those acting on his behalf could secure and even endow a fellowship for him and thereby have “something definite to put before Geddes” (Letter 12; see also Letters 15 and 19). BR definitely wanted to rededicate himself to philosophy and would have welcomed a new source of income from academic employment (see Letter 22). But the “financial aspect was quite secondary”, he reminded Frank on 24 June (Letter 27); he was interested in the fellowship plan primarily as a safeguard against being called up, for teachers over 45 were not subject to the provisions of the recently amended Military Service Act. In the same letter, however, BR told his brother that “I wish it <the plan> dropped” on account of reservations expressed to him in person by Wildon Carr and A.N. Whitehead (see also Letter 31), two philosophers whom he respected but who seemed to doubt whether BR’s financial needs were as great as they appeared (see note to Letter 102).

Yet BR’s retreat was only temporary. On 8 August, he expressed to Ottoline a renewed interest in the initiative, and a few days later, she, her husband and Gladys Rinder met in London to discuss the matter. As Ottoline reported to BR, “we all felt that it was useless to wait for others to start and we decided that P. and I should go and see Gilbert M. and try and get him to work it with the Philosophers” (11 Aug. 1918, BRACERS 114754). BR probably wanted Murray to spearhead this lobbying (see also Letters 65 and 70) because of his political respectability and prior success in persuading professional philosophers to back an appeal to the Home Secretary for BR’s sentence to be served in the first division (see Letter 6). Murray did play a leading role but not until early the following month, when BR was anxious for the fellowship plan to succeed as his release date neared. The scheme finally gathered momentum after a meeting between Ottoline, Rinder and Carr on 6 September 1918, at which the philosopher and educationist T. Percy Nunn, another academic supporter of BR, was also present. Within a few days Murray had drafted a statement with an appeal for funds, which was endorsed by Carr, Whitehead, Nunn, Samuel Alexander, Bernard Bosanquet, G. Dawes Hicks, A.E. Taylor and James Ward. This memorial was then circulated in confidence to philosophers and others, but only after BR’s release from Brixton. (Financial pledges had already been made by a few of BR’s friends and admirers, notably Lucy Silcox and Siegfried Sassoon.) BR’s solicitor, J.J. Withers, became treasurer of this endowment fund, the goal of which was to provide BR with £150 or £200 per annum over three years. On 30 August BR had confessed to Ottoline that he did not want an academic position “very far from London” (Letter 89) and reiterated this desire in a message to Murray communicated by Rinder (Letter 97). On 6 September Rinder (BRACERS 79633) hinted that she already knew where the appointment would be, but there are no other indications that a particular establishment had been decided upon. Ultimately, no affiliation was contemplated for BR, so the memorial stated, because “in the present state of public feeling no ordinary university institution is likely to be willing to employ him as a teacher” (copy in BRACERS 56750). The circular talked instead of a “special Lectureship”, and the £100 BR received from the fund early in 1919 was explicitly issued as payment for lectures (on “The Analysis of Mind”; see syllabus, in Papers 9: App. III.1) that he would deliver that spring. BR’s solicitor also informed him that provision existed to pay him a further £100 for an autumn lecture course (see syllabus, ibid.: App. III.2), and Withers anticipated that these arrangements might “last two or three years” (2 Jan. 1919, BRACERS 81764). BR had already obtained a £50 gift from the fund in November 1918. Somewhat ironically, the critical importance of a teaching component to the fellowship plan — as insurance against conscription — was reduced by the authorities hesitating to hound BR any further after his imprisonment, and all but nullified by the end of the war a few weeks later. (There were no fresh call-ups, but the last of the C.O.s already in prison were not released until August 1919, and conscription remained in effect until April 1920.)

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).

Gilbert Murray

Gilbert Murray (1866–1957), distinguished classical scholar and dedicated liberal internationalist. He was Regius Professor of Greek at Oxford, 1908–36, and chair of the League of Nations Union, 1923–36. He and BR enjoyed a long and close friendship that was ruptured temporarily by bitter disagreement over the First World War. After Murray published The Foreign Policy of Sir Edward Grey, 1906–1915, in defence of Britain’s pre-war diplomacy, BR responded with a detailed critique, The Policy of the Entente, 1904–1914: a Reply to Professor Gilbert Murray (37 in Papers 13). Yet Murray still took the lead in campaigning to get BR’s sentence reassigned from the second to the first division and (later) in leading an appeal for professional and financial backing of an academic appointment for BR upon his release (the “fellowship plan”, which looms large in his prison correspondence). BR was still thankful for Murray’s exertions some 40 years later. See his portrait of Murray, “A Fifty-Six Year Friendship”, in Murray, An Unfinished Autobiography with Contributions by His Friends, ed. Jean Smith and Arnold Toynbee (London: Allen & Unwin, 1960).

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

H. Wildon Carr

Herbert Wildon Carr (1857–1931), Professor of Philosophy at King’s College, London, from 1918 and Visiting Professor at the University of Southern California from 1925. Carr came to philosophy late in life after a lucrative career as a stockbroker. His philosophy was an idiosyncratic amalgam of Bergsonian vitalism and Leibnizian monadology, which, he thought, was supported by modern biology and the theory of relativity. He wrote books on Bergson and Leibniz at opposite ends of his philosophical career and a book on relativity in the middle. His philosophy would have made him an unlikely ally of BR’s, but it was Carr who organized BR’s two courses of public lectures, on philosophy of mathematics and the philosophy of logical atomism, which brought BR back to philosophy and improved his finances in 1917–18. Carr had great administrative talents, which he employed also on behalf of the Aristotelian Society during his long association with it. He was its president in 1916–18 and continued to edit its Proceedings until 1929.

H.A. Hollond

Captain Henry Arthur Hollond (1884–1974), in civilian life, was a legal scholar who had become friendly with BR after being elected a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1909. The two men also briefly shared rooms at Harvard in spring 1914, where Hollond was studying law and BR was lecturing on logic and epistemology (see SLBR 1: 481). A few months later Hollond enlisted and became a staff officer at British headquarters in France. He remained a Fellow of Trinity for the rest of his life and later served the college as Dean and Vice-Master, as well as holding a university professorship in English law (1943–50). BR’s presumption that Hollond would advocate for him may have been misplaced. When he returned to Trinity in 1944, BR was deeply hurt after seeing a letter indicating that Hollond had not supported him when he was dismissed from his lectureship at the college in 1916. He stewed over this early betrayal until finally initiating a break from Hollond in 1964 (BRACERS 7637).

J.E. Littlewood

John Edensor Littlewood (1885–1977), mathematician. In 1908 he became a fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, and remained one for the rest of his life. In 1910 he succeeded Whitehead as college lecturer in mathematics and began his extraordinarily fruitful, 35-year collaboration with G.H. Hardy. During the First World War he worked on ballistics for the British Army. He and BR were to share Newlands farm, near Lulworth, during the summer of 1919. Littlewood had two children, Philip and Ann Streatfeild, with the wife of Dr. Raymond Streatfeild.

Philip Morrell

Philip Morrell, Ottoline’s husband (1870–1943), whom she had married in 1902 and with whom, four years later, she had twins — Julian, and her brother, Hugh, who died in infancy. The Morrells were wealthy Oxfordshire brewers, although Philip’s father was a solicitor. He won the Oxfordshire seat of Henley for the Liberal Party in 1906 but held this Conservative stronghold only until the next general election, four years later. For the second general election of 1910 he ran successfully for the Liberals in the Lancashire manufacturing town of Burnley. But Morrell’s unpopular anti-war views later cost him the backing of the local Liberal Association, and his failure to regain the party’s nomination for the post-war election of 1918 (see Letter 89) effectively ended his short political career. Unlike many other Liberal critics of British war policy (including BR), Morrell did not transfer his political allegiance to the Labour Party. Although Ottoline and her husband generally tolerated each other’s extra-marital affairs, a family crisis ensued when in 1917 Philip impregnated both his wife’s maid and his secretary (see Letter 48).

Samuel Alexander

The Australian-born British philosopher Samuel Alexander (1859–1938) was originally an Hegelian whose outlook gradually shifted towards realism. He tutored at Lincoln College, Oxford, for more than a decade before accepting in 1893 a professorship at the University of Manchester, where he remained for the rest of his career. A former President of the Aristotelian Society (1908–11), Alexander joined Gilbert Murray and H. Wildon Carr in urging academic philosophers to endorse their appeal to the Home Secretary for BR to be assigned the status of a first-division prisoner (see Papers 14: 395).

Sir Auckland Geddes

Sir Auckland Geddes (1879–1954; 1st Baron Geddes, 1942) was returned unopposed as Conservative M.P. for Basingstoke in a by-election held in October 1917. Before this entry into civilian public life, he held the rank of Brigadier-General as director of recruiting at the War Office. He was an ardent champion of conscription even in peacetime and had a long-standing interest in the military, which he expressed before the war as a volunteer medical officer in the British Army Reserve. He had studied medicine and was Professor of Anatomy at McGill University, Montreal, when the outbreak of war prompted an immediate return to Britain in order to enlist. After a riding accident rendered Geddes unfit for front-line duties, he became a staff officer in France with a remit covering the supply and deployment of troops. He performed similar duties at the War Office until his appointment in August 1917 as a Minister of National Service with broad powers over both military recruitment and civilian labour. Geddes held two more Cabinet positions in Lloyd George’s post-war Coalition Government before his appointment in 1920 as British Ambassador to the United States. After returning from Washington on health grounds three years later, Geddes embarked upon a successful business career, becoming chairman in 1925 of the Rio Tinto mining company. See Oxford DNB.

T.S. Eliot

The poet and critic Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888–1965) was a student of BR’s at Harvard in 1914. BR had sensed his ability, especially “a certain exquisiteness of appreciation” (to Lucy Donnelly, 11 May 1914; SLBR 1: 491), but did not see a genius in embryo. After Eliot travelled to England later the same year, to study philosophy at Oxford under H.H. Joachim, BR became something of a father figure to the younger man. He also befriended Eliot’s (English) wife, Vivienne, whom he had hastily married in 1915 and with whom BR may have had an affair the following year. BR shared his Bloomsbury apartment (at 34 Russell Chambers) with the couple for more than a year after their marriage, and jointly rented a property with them in Marlow, Bucks. (see Letter 78). He further eased Eliot’s monetary concerns by arranging paid reviewing for him and giving him £3,000 in debentures from which BR was reluctant, on pacifist grounds, to collect the income (Auto. 2: 19). Eliot’s financial security was much improved by obtaining a position at Lloyd’s Bank in 1917, but during BR’s imprisonment he faced uncertainty of a different kind as the shadow of conscription loomed over him (see, e.g., Letter 27). Nine years after the war ended Eliot returned the securities (BRACERS 76480).

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.