Brixton Letter 18

BR to Clifford Allen

June 16, 1918

- TL(TC)

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-18Papers 14: 98

BRACERS 131594

<Brixton Prison>

<18 June 1918>

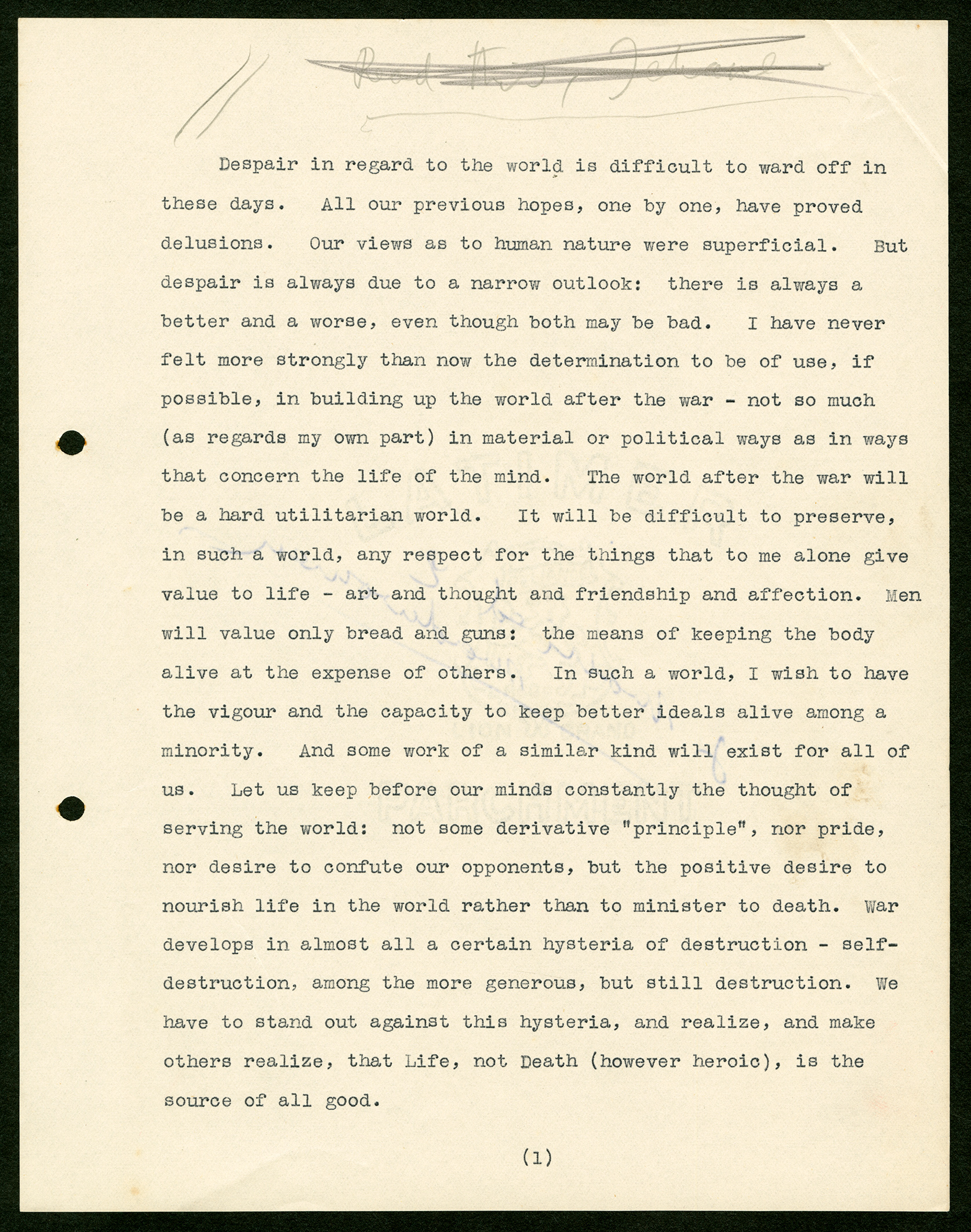

Despair in regard to the world1 is difficult to ward off in these days. All our previous hopes, one by one, have proved delusions. Our views as to human nature were superficial. But despair is always due to a narrow outlook: there is always a better and a worse, even though both may be bad. I have never felt more strongly than now the determination to be of use, if possible, in building up the world after the war — not so much (as regards my own part) in material or political ways as in ways that concern the life of the mind. The world after the war will be a hard utilitarian world. It will be difficult to preserve, in such a world, any respect for the things that to me alone give value to life — art and thought and friendship and affection. Men will value only bread and guns: the means of keeping the body alive at the expense of others. In such a world, I wish to have the vigour and the capacity to keep better ideals alive among a minority. And some work of a similar kind will exist for all of us. Let us keep before our minds constantly the thought of serving the world: not some derivative “principle”, nor pride, nor desire to confute our opponents, but the positive desire to nourish life in the world rather than to minister to death. War develops in almost all a certain hysteria of destruction — self-destruction, among the more generous, but still destruction. We have to stand out against this hysteria, and realize, and make others realize, that Life, not Death (however heroic), is the source of all good.

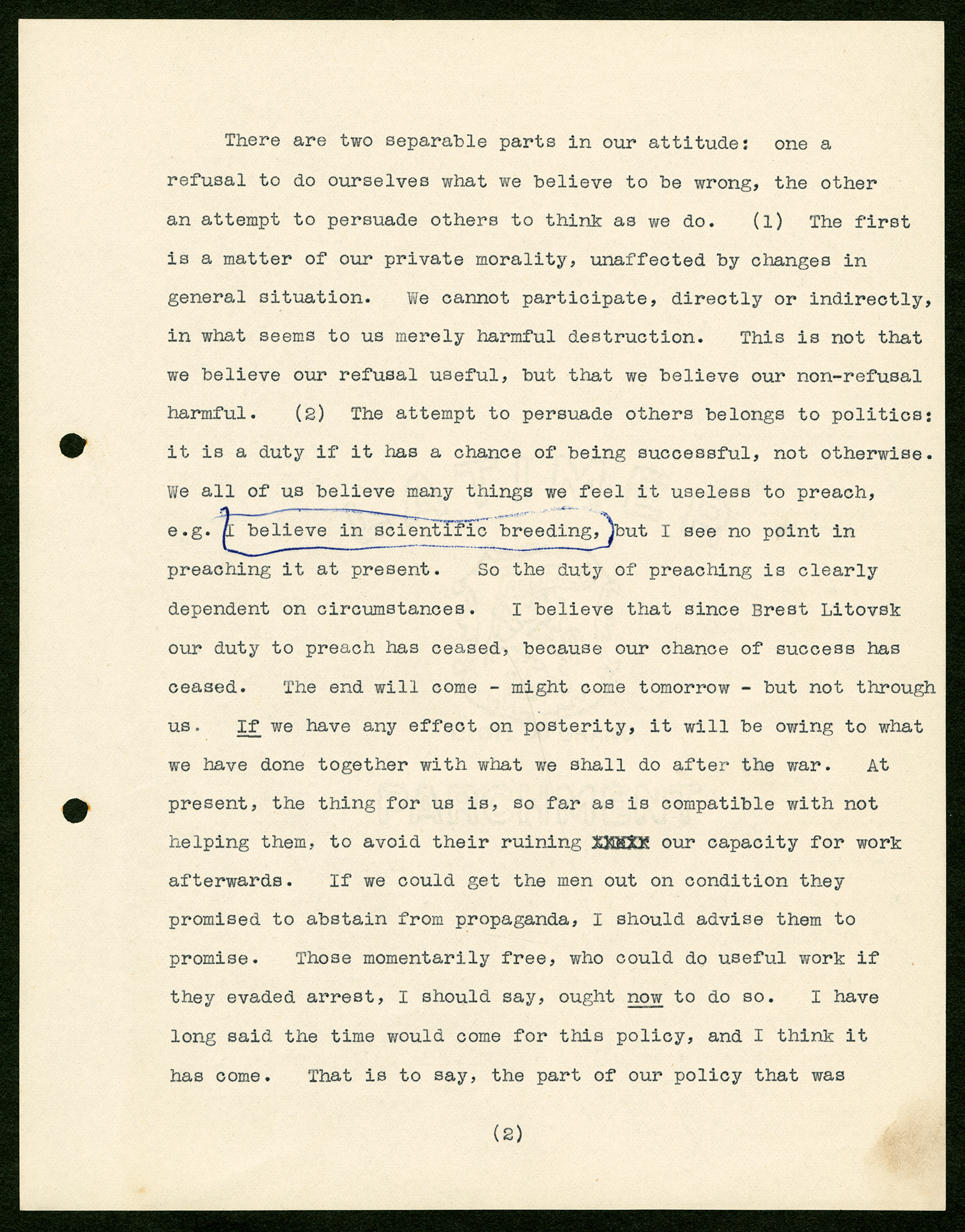

There are two separable parts in our attitude: one a refusal to do ourselves what we believe to be wrong, the other an attempt to persuade others to think as we do. (1) The first is a matter of our private morality, unaffected by changes in <the> general situation. We cannot participate, directly or indirectly, in what seems to us merely harmful destruction. This is not that we believe our refusal useful, but that we believe our non-refusal harmful. (2) The attempt to persuade others belongs to politics: it is a duty if it has a chance of being successful, not otherwise. We all of us believe many things we feel it useless to preach, e.g. I believe in scientific breeding,2 but I see no point in preaching it at present. So the duty of preaching is clearly dependent on circumstances. I believe that since Brest Litovsk our duty to preach has ceased, because our chance of success has ceased.3 The end will come — might come tomorrow — but not through us. If we have any effect on posterity, it will be owing to what we have done together with what we shall do after the war. At present, the thing for us is, so far as is compatible with not helping them, to avoid their ruining our capacity for work afterwards. If we could get the men out on condition they promised to abstain from propaganda, I should advise them to promise. Those momentarily free, who could do useful work if they evaded arrest, I should say, ought now to do so. I have long said the time would come for this policy, and I think it has come. That is to say, the part of our policy that was political (aimed at affecting public opinion) should be altered. It is a duty to attempt to stop a runaway horse, at whatever personal risk, but not a runaway express train. Our political duty, now, I hold, is entirely to be in readiness for after the war, and efficient when that times comes (if ever).

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from an untitled typed copy in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. There is another copy elsewhere in the Russell Archives and one in the Morrell papers at Texas. The letter was originally enclosed as a manuscript of two sheets with BR’s letter to Ottoline of 16 June 1918: “Please send the next two sheets to C.A. (Hawse End Keswick) after reading them.” Ottoline wrote in her next letter in a way that reveals that she had read the letter: “I feel very strongly about surviving the War and keeping together a few souls who have The Light. They will be Needed dreadfully. — It will be a bitter world afterwards. — That is one of the New painful things one has to face. This cruel feeling — bitterness — and as you and I did Not cause it — It seems hard!!” (BRACERS 114747). Gladys Rinder wrote BR about the document in a letter of very late June or early July: “CA sent me that note and asked me to have part of it copied. You have put into words what many of us have been groping for.... I do so thoroughly agree with what you say about ‘serving the world’ through ‘the positive desire to nourish life in the world rather than minister to death.’” (This suggests that there was more to the original letter than the statement-like extract printed here.) The quotations are from the document. Siegfried Sassoon, who was shown a version of it in hospital in early August 1918 (Ottoline to BR, BRACERS 114753), regarded it as a letter to Lady Ottoline and copied it into his diary. He remarked first that death was a stimulus to life. “Bertrand Russell said it, very finely, in a letter (to Ottoline Morrell) written in 1918, when he was in prison: ‘I wish to have the vigour and capacity to keep better ideals alive among a minority<....> We have to stand out against this hysteria and realise, and make others realise, that life, not death (however heroic) is the source of all good.’ I ask no better credo than that” (Sassoon, Diaries 1920–1922, ed. Rupert Hart-Davis [London: Faber and Faber, 1981], p. 191). The letter was published as 98 in Papers 14.

- 2

scientific breeding Like many of his progressive contemporaries, BR was influenced by the early-twentieth-century vogue for eugenics. His advocacy of birth control can be understood in this light, but so can his approval of compulsory sterilization for the “feeble-minded” (see Marriage and Morals [London: Allen & Unwin, 1929], p. 166). At root, BR was driven by a concern that the poorest and least intelligent sections of the population were reproducing the most rapidly. While he shared questionable eugenic assumptions about heritability, he regarded the supposed dysgenic effects of this “differential birth-rate” as more socially than biologically determined. He could therefore graft his understanding of eugenics onto an ideology of social reform, whereas many eugenists took a Social Darwinist and laissez-faire view of the state (see Stephen Heathorn, “Explaining Russell’s Eugenic Discourse in the 1920s”, Russell 25 [2005]: 107–39). Although BR later sensed the totalitarian implications of “scientific breeding” — especially after the entire eugenics movement was discredited by Nazi racial theories and policies — he never completely disavowed this contentious strain of social thought (see Auto. 3: 173).

- 3

since Brest Litovsk our duty … chance of success has ceased This separate peace between the Bolsheviks and the Central Powers (signed on 3 March 1918) formally ended Russian participation in the war and allowed Germany to concentrate its military resources on the Western Front. While Allied leaders were alarmed by the strategic implications of the treaty, British peace campaigners were disheartened by the grasping territorial gains made by the Central Powers at the expense of the former Tsarist Empire. Many, including BR, had argued hitherto that Germany would be amenable to a general peace without annexations or indemnities if only the Allies signalled their willingness to compromise. See also Letter 9.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

Siegfried Sassoon

Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967), soldier awarded the MC and anti-war poet. Ottoline had befriended him in 1916, and the following year, when Sassoon refused to return to his regiment after being wounded, she and BR helped publicize this protest, which probably saved him from a court martial. BR even assisted Sassoon in revising his famous anti-war statement, which was read to the House of Commons by a Liberal M.P. on 30 July 1917. Sassoon’s actions were an embarrassment to the authorities, for he was well known as both a poet and a war hero. Unable to hush the case up, the government acted with unexpected subtlety and declared Sassoon to be suffering from shell-shock and sent him to Craiglockhart War Hospital for Officers, near Edinburgh. After a period of recuperation in Scotland overseen by military psychiatrist Capt. W.H.R. Rivers, Sassoon decided to return to the Front (see Jean Moorcroft Wilson, Siegfried Sassoon: Soldier, Poet, Lover, Friend [New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2014]). He was again wounded in July 1918 and was convalescing in Britain during some of BR’s imprisonment. Although each admired the other’s stand on the war, BR and Sassoon were never close in later years. Yet Sassoon did pledge £50 to the fellowship plan fund (see BRACERS 114758), and decades later he donated a manuscript in support of BR’s International War Crimes Tribunal (see BRACERS 79066).

Clifford Allen

(Reginald) Clifford Allen (1889–1939; Baron Allen of Hurtwood, 1932) was a socialist politician and publicist who joined the Cambridge University Fabian Society while studying at Peterhouse College (1908–11). After graduating he became active in the Independent Labour Party in London and helped establish a short-lived labour newspaper, the Daily Citizen. During the war Allen was an inspiring and effective leader of the C.O. movement as chairman of the No-Conscription Fellowship, which he co-founded with Fenner Brockway in November 1914. Court-martialled and imprisoned three times after his claim for absolute exemption from war service was rejected, Allen became desperately ill during his last spell of incarceration. He was finally released from the second division of Winchester Prison on health grounds in December 1917, but not before contracting the tuberculosis with which he was finally diagnosed in September 1918. He was dogged by ill health for the rest of his life. BR had enormous affection and admiration for Allen (e.g., 68 in Papers 13, 46 in Papers 14), a trusted wartime political associate. From February 1919 until March 1920 he even shared Allen’s Battersea apartment. A close friendship was soured, however, by Allen’s rejection of BR’s unforgiving critique of the Bolshevik regime, which both men witnessed at first hand with the British Labour Delegation to Russia in May 1920 (see Papers 15: 507). Yet Allen was far from revolutionary himself and did not even identify with the left wing of the ILP (which he chaired in the early 1920s). He was elevated to the peerage as a supporter of Ramsay MacDonald’s National Government, an administration despised by virtually the entire labour movement. Although Allen’s old intimacy with BR was never restored after the Russia trip, any lingering estrangement did not inhibit him from enrolling his daughter, Joan Colette (“Polly”) at the Russells’ Beacon Hill School.