Brixton Letter 15

BR to Frank and Elizabeth Russell

June 10, 1918

- ALS

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-15

BRACERS 46919

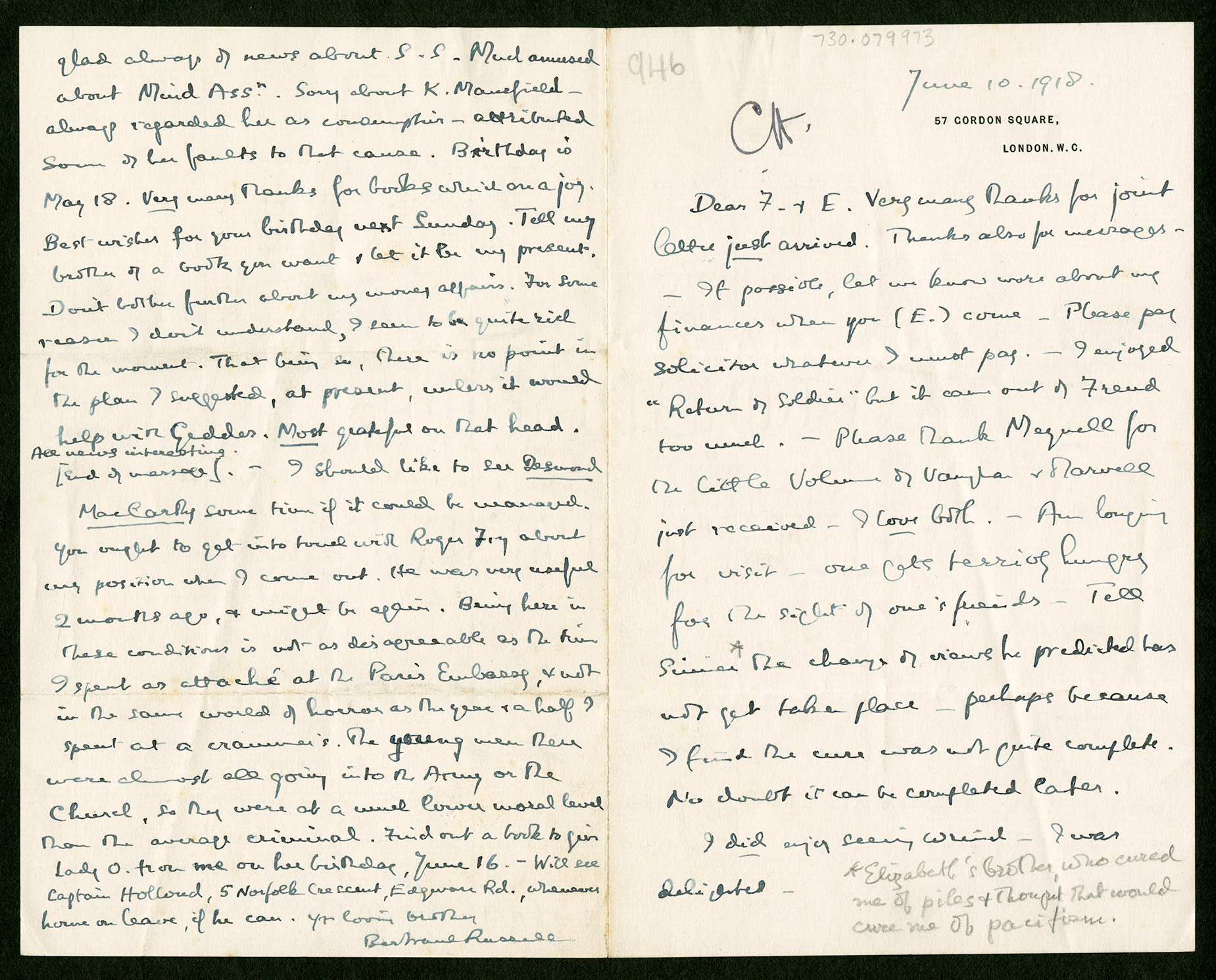

<letterhead>1, 2

57 GORDON SQUARE

LONDON. W.C.

[Brixton Prison]a

June 10. 1918.

Very many thanks for joint letter3 just arrived. Thanks also for messages. — If possible, let me know more about my finances when you (E.) come. Please pay solicitor4 whatever I must pay. — I enjoyed Return of Soldier5 but it came out of Freud too much. — Please thank Meynell for the little Volume of Vaughan and Marvell6 just received — I love both. — Am longing for visit — one gets terribly hungry for the sight of one’s friends. Tell Sinner7 the change of views he predicted has not yet taken place — perhaps because I find the cure was not quite complete. No doubt it can be completed later.

I did enjoy seeing Wrinch8 — I was delighted.

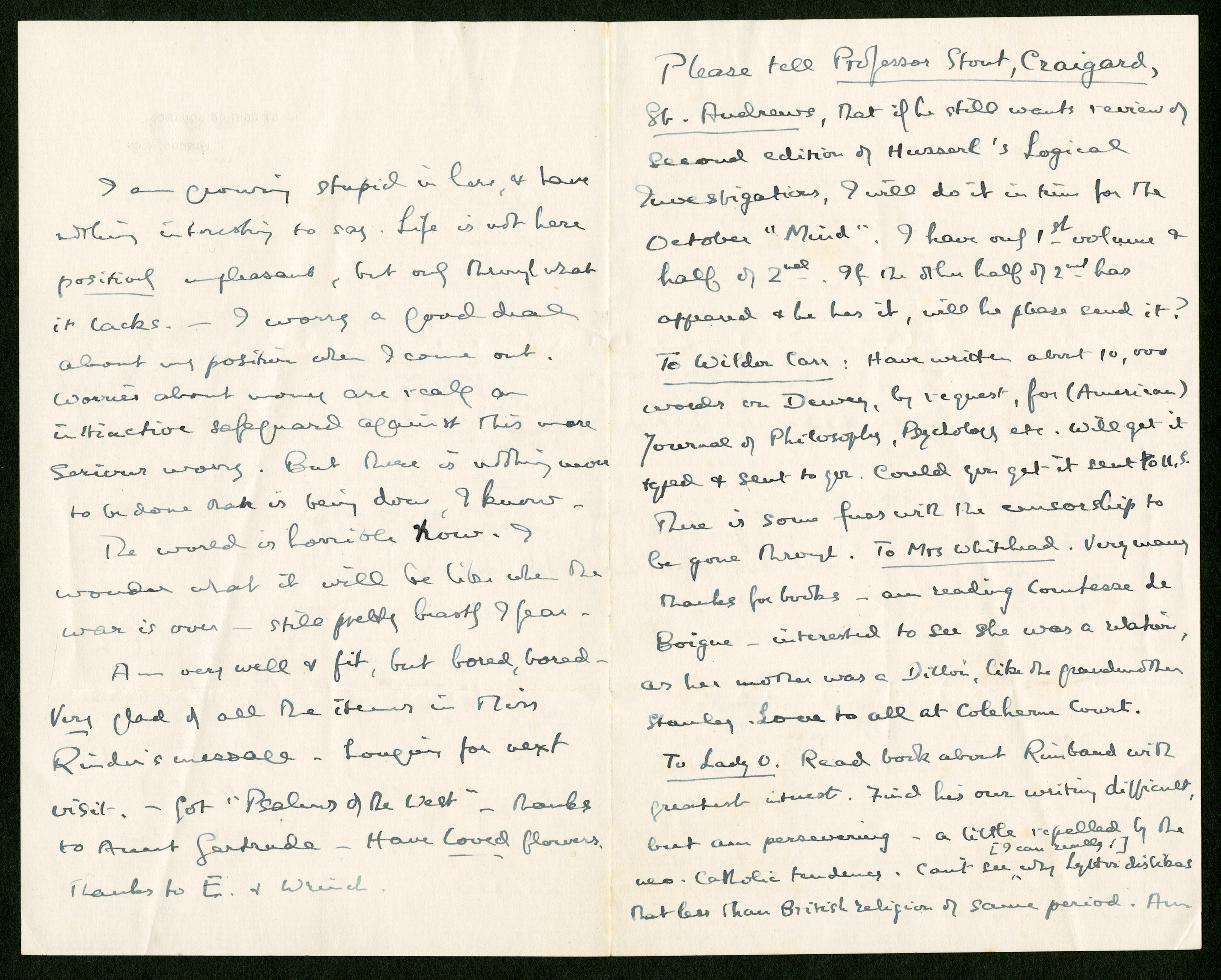

I am growing stupid in here, and have nothing interesting to say. Life is not here positively unpleasant, but only through what it lacks. — I worry a good deal about my position when I come out.9 Worries about money are really an instinctive safeguard against this more serious worry. But there is nothing more to be done than is being done, I know.

The world is horrible now. I wonder what it will be like when the war is over — still pretty beastly I fear.

Am very well and fit, but bored, bored. Very glad of all the items in Miss Rinder’s message.10 Longing for next visit. — Got Psalms of the West — thanks to Aunt Gertrude.11 Have loved flowers. Thanks to E. and Wrinch.

Please tell Professor Stout, Craigard, St. Andrews, that if he still wants review of second edition of Husserl’s Logical Investigations,12 I will do it in time for the October Mind. I have only 1st volume and half of 2nd.13 If the other half of 2nd has appeared and he has it, will he please send it? To Wildon Carr: Have written about 10,000 words on Dewey,14 by request, for (American) Journal of Philosophy, Psychology etc. Will get it typed and sent to you. Could you get it sent to U.S. There is some fuss with the censorship to be gone through. To Mrs. Whitehead. Very many thanks for books — am reading Comtesse de Boigne — interested to see she was a relation, as her mother was a Dillon, like the grandmother Stanley.15 Love to all at Coleherne Court.16

To Lady O. Read book about Rimbaud with greatest interest. Find his own writing difficult,17 but am persevering — a little repelled by the neo-Catholic tendency. Can’t see [I can really!]b why Lytton dislikes that less than British religion of same period.18 Am glad always of news about S.S. Much amused about Mind Assn.19 Sorry about K. Mansfield — always regarded her as consumptive20 — attributed some of her faults to that cause. Birthday is May 18.21 Very many thanks for books which are a joy. Best wishes for your birthday next Sunday. Tell my brother of a book you want and let it be my present. Don’t bother further about my money affairs. For some reason I don’t understand, I seem to be quite rich for the moment.22 That being so, there is no point in the plan I suggested, at present, unless it would help with Geddes. Most grateful on that head. All news interesting.c [End of message]. — I should like to see Desmond MacCarthy some time if it could be managed. You ought to get into touch with Roger Fry about my position when I come out. He was very useful 2 months ago,23 and might be again. Being here in these conditions is not as disagreeable as the time I spent as attaché24 at the Paris Embassy, and not in the same world of horror as the year and a half I spent at a crammer’s. The young men there25 were almost all going into the Army or the Church, so they were at a much lower moral level than the average criminal. Find out a book to give Lady O. from me on her birthday, June 16. — Will see Captain Hollond, 5 Norfolk Crescent, Edgware Rd., whenever home on leave, if he can.

Yr loving brother

Bertrand Russell

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the signed original in BR’s hand in the Frank Russell files in the Russell Archives. It was an “official” letter, approved by “CH”, the Prison Governor, despite being written on a single sheet of Frank Russell’s stationery. BR first made an outline of points to cover in the letter (all of which he did cover, though not quite in the same order). The outline is found on the verso of a half-sheet of BR’s notes on John B. Watson’s Behavior <i.e., Behaviorism> (New York: 1914) (RA 210.006574):

Messages.

To Stout about Husserl Hope see Desmond soon.

To Carr about Dewey Mrs Wd.: Thanks for books — interesting.

To O.: Wish I could see Garsington — amused about Mind Ass

Rimbaud — life interesting — find his work difficult — am persevering.

— Am glad of any news about S.S.

Sorry about K. Mansfield; always thought her consumptive.

Birthday: May 18. Books — very many thanks —

No news dull.

Prison not as bad as Paris Embassy — not nearly as bad as crammer’s. - 2

[BR’s note] “The above letter had to pass the censorship of the Governor of the prison, and was not allowed to fill more than one sheet. Hence the style.” (BR’s note at BRACERS 116580.)

- 3

joint letter From Frank and Elizabeth Russell, dated 6 June 1918 (BRACERS 46918).

- 4

pay solicitor I.e., Withers, for his visit concerning BR’s next publishing contract; see Letter 21.

- 5

I enjoyed Return of SoldierThe Return of the Soldier (London: Nisbet, 1918) is a fictional treatment by British writer Rebecca West (penname of Cicely Isabel Fairchild, 1892–1983) of the dramatic recovery, through psychoanalysis, of a shell-shocked British army officer. BR knew the author slightly from his acquaintance with her lover, H.G. Wells.

- 6

Please thank Meynell ... little Volume of Vaughan and MarvellHenry Vaughan, 1621–1695, Silurist; and Andrew Marvell, 1621–1678, Sometime M.P.: The Best of Both Worlds: A Choice Taken from Their Poems (London: Pelican P., 1918; Russell’s library). BR’s NCF colleague Francis Meynell had edited this anthology of metaphysical poetry and published it under the imprint of the small socialist press that he owned and managed. It was known for its outstanding typography.

- 7

Sinner “Nickname of Elizabeth’s brother, who cured me of piles and thought that would cure me of pacifism.” (BR’s note on original; revised by him at BRACERS 116580.) Sir Sydney Beauchamp (1861–1921), M.B., B.Ch., physician. He became resident medical officer with the British delegation at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. He was killed in a motor-bus accident.

- 8

I did enjoy seeing WrinchWrinch had visited BR on 5 June, with Frank and Elizabeth Russell.

- 9

my position when I come out BR was referring to the possibility of his being called up under the revised Military Service Act, against which unnerving prospect he had hatched, as a possible safeguard, the fellowship plan.

- 10

all the items in Miss Rinder’s message Her message was in Frank and Elizabeth’s letter of 6 June (BRACERS 46918). The most important item in it for BR would have been that Colette had not seen her sometime lover Maurice Elvey (see note 6 to Letter 22) since she left London. The message also referred to use of the International Journal; see Letter 12, note 4.

- 11

Got Psalms of the West — thanks to Aunt Gertrude Francis Albert Rollo Russell, Psalms of the West (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, 1889; Russell’s library): religious verse composed by BR’s unconventionally devout Uncle Rollo (1849–1914) and received courtesy of the latter’s second wife, “Aunt Gertrude”, i.e. Gertrude Ellen Cornelia Russell (1865–1942), sister of the Oxford idealist philosopher, H.H. Joachim.

- 12

Professor Stout, Craigard… review of … Husserl’s Logical Investigations A Cambridge philosopher who had been one of BR’s undergraduate tutors, George Frederick Stout (1860–1944) was editor of Mind from 1891 to 1920. Although BR never reviewed Logische Untersuchungen (2nd ed., 2 vols. [Halle: Max Niemeyer, 1913, Part 1 of Vol. 2; 1921, Part 2 of Vol. 2]), his prison reading did include the first volume of this “vast book” (Letter 12) by the German founder of phenomenology, Edmund Husserl (1859–1938). Instead, “in time for the October Mind”, BR completed for Stout a review (1918; 15 in Papers 8) of C.D. Broad’s Perception, Physics, and Reality (1914; see Letter 30, especially note 3).

- 13

I have only 1st volume and half of 2nd. The second edition of the second volume of Husserl’s book was in two parts; the second part did not appear until 1921.

- 14

10,000 words on Dewey See “Professor Dewey’s Essays in Experimental Logic”, The Journal of Philosophy, Psychology and Scientific Methods 16 (2 Jan. 1919): 5–26 (16 in Papers 8), a surprisingly conciliatory defence of his own views against Dewey’s criticism. Eva Kyle must have typed the review promptly, and BR received proofs and the copyedited typescript by the end of the summer (Letter 95, notes 11 and 12). BR’s library has the copy of Essays in Experimental Logic (Chicago: U. of Chicago P., 1916) annotated during his imprisonment.

- 15

am reading Comtesse de Boigne … a Dillon, like the grandmother Stanley Charles Nicoullaud, ed., Memoirs of the Comtesse de Boigne, 3 vols. (London: Heinemann, 1907). Adèle d’Osmond, Comtesse de Boigne (1781–1866) was descended on her mother’s side from an émigré branch of the same aristocratic family as her distant cousin and BR’s maternal grandmother, Lady Stanley (née Henrietta Maria Dillon-Lee, 1807–1895). Irish Jacobite refugees originally, these “French” Dillons were quickly assimilated into the military, diplomatic, ecclesiastical and court life of the ancien régime. For example, the future Comtesse was raised at the Palace of Versailles, and her ancestral relationship to BR can be traced through her uncle, Arthur Dillon, Archbishop of Narbonne, whose nephew was the family’s titular head, the 12th Viscount Dillon (BR’s great-great-grandfather), an Irish peer who had abjured his Catholicism in order to become fully integrated into British aristocratic life. The Comtesse would flee to England as a royalist refugee from the French Revolution, return to France under Napoleon’s imperial rule, but only regain lost privileges and position after the Bourbon Restoration, during which she achieved considerable renown as the hostess of a dazzling Parisian salon.

- 16

Coleherne Court Where Alfred and Evelyn Whitehead lived.

- 17

Find his own writing difficult In a message for Ottoline in Letter 20 to Gladys Rinder, BR indicated that he had read Rimbaud’s Une saison en enfer, a long prose poem published by the author in 1873.

- 18

Read book about Rimbaud … neo-Catholic tendency … same period Probably Paterne Berrichon, Jean-Arthur Rimbaud, le poète (1854–1873) (Paris: Mercure de France, 1912), which contains some discussion (pp. 290–1) of the Catholic bent of Une saison en enfer, a long prose poem published by the French symbolist in 1873. Also, on 15 August 1918, BR asked Colette to “Please send Paterne Berrichon on Rimbaud to Ottoline — it is hers and she wants it” (Letter 71). BR seems to have been teasing Ottoline about Rimbaud, whom both she (BRACERS 11746) and Lytton Strachey esteemed more than he did. The poet did not feature in Strachey’s Landmarks in French Literature (1912), but he discovered him a few years later and assured his brother James that “Rimbaud … is a good poet” (31 May 1916; quoted in Strachey’s The Really Interesting Question, and Other Papers, ed. Paul Levy [London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1972], p. 34). In Eminent Victorians Strachey mocked the early-Victorian Oxford Movement, which emphasized the common ground between Anglican and Catholic theology. One of Strachey’s subjects, Cardinal Manning, identified with this influential High Church faction before taking his Tractarianism a step further and converting to Catholicism in 1851.

- 19

Much amused about Mind Assn. Formed in 1900, the Mind Association remains one of the two most important philosophical bodies in Britain. BR may well have been a founding member (David Holdcroft, “Eighty-Seven Years of Minutes”, Mind 96 [1987]: 141–4). At the annual general meeting of the Association in early July 1918, Charles A. Mercier, a physician-philosopher whom BR had reviewed in 1912 (9 in Papers 6), proposed that “no person who had been convicted of felony or of a serious offence against the Defence of the Realm Act be admitted or allowed to continue as a member of the Association.” Obviously BR was a target of the rule, if not the only target. The rule failed to be accepted (Papers 6: 70–1). Ottoline had forwarded a clipping that Mrs. Hamilton had given her: “Philosophy and Pacifism: the Mind Association and the Case of Bertrand Russell”, Evening News, 29 May 1918. It reported an interview with Mercier. He had tried in January “to move a resolution that Mr. Russell should cease to be a member. The resolution was ruled out of order.” Now he was trying a different sort of resolution, omitting BR’s name. Mercier admitted: “I don’t suppose I shall get a single vote.…” For more about Mercier and his attempt to expel BR, see Dorothy Wrinch’s undated but early July 1918 letter about the meeting, BRACERS 81965.

- 20

K. Mansfield … always regarded her as consumptiveKatherine Mansfield was indeed consumptive. In the spring of 1918 she had gone to the south of France for the sake of her health, but then precipitately fled back through war-torn France to England, arriving in much worse condition than she left. Consumption was definitively diagnosed just before her marriage to J. Middleton Murry on 3 May 1918. Ottoline had reported, “It was a great shock to see her”; she had returned from France “quite changed — I fear consumption — very thin” (letter of 1 June 1918, BRACERS 114746).

- 21

Birthday is May 18Ottoline had asked whether BR’s birthday was 18 May or June (letter of 1 June 1918, BRACERS 114746).

- 22

quite rich for the moment In his pocket diary, at an unspecified date in June, BR recorded receiving from Allen & Unwin a payment of £61.15.3. The purchasing power of that sum was not negligible. In Letter 87, for example, BR allotted £1 to buy a presentfor Gladys Rinder for her efforts on his behalf. When there was a plan for Colette to rent his flat, the charge was to be 2 guineas (£2.2.0) a week (Letter 71). And he considered that he needed, after his release, “to earn at least £200 a year somehow” (Letter 12). In addition, Frank had told him on 31 May: “Clough <A.H. Clough and Miss B.A. Clough (BRACERS 80113)>is altering the security in your Marriage Settlement funds on his mortgage of £3600, and raising the interest from 4% to 5½%, which should give you an additional £54 a year” (BRACERS 46916). Colette, on the other hand, did not have BR’s concern to live within his earned income. Her earned income was very low at this time, but she had a sizeable unearned income (“Letters to Bertrand Russell from Constance Malleson, 1916–1969”, pp. 86–7 [typescript in RA]).

- 23

Roger Fry ... very useful 2 months ago As with so many of his lifelong friends, BR became acquainted with Roger Fry (1866–1934) at Trinity College, Cambridge. He remained close to his slightly older contemporary, the Bloomsbury painter and art historian and critic. Fry’s 1923 portrait of BR hangs in London’s National Portrait Gallery. How Fry had been recently useful to BR (it was during the time of his appeal) could not be determined.

- 24

time I spent as attaché BR was an honorary attaché at the British Embassy in Paris from 10 September to 1 December 1894. He accepted the position at the insistence of his grandmother, who was trying to separate him from Alys Pearsall Smith. They married as soon as the separation came to an end. He soon regretted accepting the position from the ambassador, Lord Dufferin, because almost immediately afterwards he received a more tempting offer to serve as private secretary to Radical Liberal M.P. John Morley.

- 25

year and a half I spent at a crammer’s. … young men there In preparation for the Trinity College scholarship examination, which he sat in December 1889, BR was a student for eighteen months at B.A. Green’s University and Army Tutors, in Southgate, London. A notebook in the Russell Archives preserves seven essays (2–8 in Papers 1) he wrote at this “Army crammer”, as he unflatteringly remembered the institution in his Autobiography (1: 42).In a deleted passage in a much later writing, “The Importance of Shelley” (1956), BR recalled his reaction to his fellow pupils: “Until I went to Cambridge, most of my contemporaries whom I knew filled me with disgust, so that my love of the human species was tempered by loathing of most of the examples I came across” (Papers 29: 586–7).

Textual Notes

57 Gordon Square

The London home of BR’s brother, Frank, 57 Gordon Square is in Bloomsbury. BR lived there, when he was in London, from August 1916 to April 1918, with the exception of January and part of February 1917.

A.N. Whitehead

Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947), Cambridge-educated mathematician and philosopher. From 1884 to 1910 he was a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, and lecturer in mathematics there; from 1911 to 1924 he taught in London, first at University College and then at the Imperial College of Science and Technology; in 1924 he took up a professorship in philosophy at Harvard and spent the rest of his life in America. BR took mathematics courses with him as an undergraduate, which led to a lifelong friendship. Whitehead’s first major work was A Treatise on Universal Algebra (1898), which treated selected mathematical theories as “systems of symbolic reasoning”. Like BR’s The Principles of Mathematics (1903), it was intended as the first of two volumes; but in 1900 he and BR discovered Giuseppe Peano’s work in symbolic logic, and each decided to set aside his projected second volume to work together on a more comprehensive treatment of mathematics using Peano’s methods. The result was the three volumes of Principia Mathematica (1910–13), which occupied the pair for over a decade. After Principia was published, Whitehead’s interests, like BR’s, turned to the empirical sciences and, finally, after his move to America, to pure metaphysics. See Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: the Man and His Work, 2 vols. (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins U. P., 1985–90).

Annotations by BR

In the late 1940s, when BR was going through his archives, and in the 1950s when he was revising his Autobiography, he would occasionally annotate letters. He did this to sixteen of the Brixton letters. Links to them are gathered here for convenient access to these new texts. In the annotations to the letters they are always followed by “(BR’s note.)”

Letter 2, note 5 happy.

5, note 6 congratulations to G.J.

9, note 28 bit of Girondin history.

12, note 6 friend.

15, note 2 (the letter in general).

20, note 7 G.J.

31, note 3 Dr’s treatment.

40, notes 9, 10 Ld. G.L.G, Lady B’s.

44, note 14 S.S.

48, note 48 Mother Julian’s Bird.

57, notes 13, 16 Ld. Granville’s to Ly. B., bless that Dr. … seat of intellect.

70, note 15 Mrs Scott.

73, note 12 E.S.P. Haynes.

76, note 4 Cave.

85, note 2 Marsh on Rupert.

102, notes 23, 28 Woolley, K. Lonsdale.

General Annotations

Brett note from Auto. 2: 93

Cousens note from Auto. 2: 71

Kyle note with her letters to BR

Rinder note from Auto. 2: 88n.

Silcox note on BRACERS 80365

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

C.D. Broad

Charlie Dunbar Broad (1887–1971), British philosopher, studied at Trinity College, Cambridge (1906–10), where he came in contact with BR, whose work had the greatest influence on him, though he was taught primarily by W.E. Johnson and J.M.E. McTaggart. (He wrote the definitive refutation of McTaggart’s philosophy after the latter’s death.) In 1911 BR examined Broad’s fellowship dissertation, which was published as Perception, Physics, and Reality (1914) and which BR reviewed in Mind in 1918 (15 in Papers 8). BR reviewed more books by Broad in the 1920s, and Broad returned the favour over the decades. Outstanding among his reviews was that of the first volume of BR’s Autobiography in The Philosophical Review 77 (1968): 455–73. From 1911 to 1920 Broad taught at St. Andrews University; in 1920 he moved to Bristol as Professor of Philosophy before returning to Trinity in 1923, where, as Knightbridge Professor of Moral Philosophy, he remained for the rest of his life. He wrote extensively on a wide range of philosophical topics, including ethics, philosophy of mind, philosophy of science, and psychical research. His philosophical writings are marked by the impartiality and clarity with which he stated, revised, and assessed the arguments and theories with which he was dealing, rather than by originality in his own position. BR and Moore were the two philosophers with whose views his were most closely aligned. Broad was evidently devoted to BR. One of the current editors was introduced to Broad upon visiting Trinity College Library in 1966. He was keen to hear about BR from someone who had recently talked with him. Following BR’s death Broad introduced a reprint of G.H. Hardy’s Bertrand Russell and Trinity: a College Controversy of the Last War (Cambridge U. P., 1944; 1970).

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.

Desmond MacCarthy

(Charles Otto) Desmond MacCarthy (1877–1952), literary critic, Cambridge Apostle, and a friend of BR’s since their Trinity College days in the 1890s. MacCarthy edited the Memoir (1910) of Lady John Russell.

Dorothy Wrinch

Dorothy Maud Wrinch (1894–1976), mathematician, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. She studied mathematics and philosophy at Girton College, Cambridge, and came under BR’s influence in her second year when she took his course on mathematical logic. She taught mathematics at University College, London, 1918–21, and then at Oxford, 1922–30. Her first publications were in mathematical logic and philosophy, and during the 1920s she wrote on the philosophy of science. But in the 1930s her interests turned to mathematical biology and crystallography, and in 1935 she moved to the United States on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship and remained there for the rest of her life. Unfortunately, as a biologist she is best known for a long and stubborn controversy with Linus Pauling about the structure of proteins in which he was right and she was wrong. See Marjorie Senechal, I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science (New York: Oxford U. P., 2013). Chapter 7 is devoted to Wrinch’s interactions with BR in Brixton.

Elizabeth Russell

Elizabeth Russell, born Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941), was a novelist who in 1891 married Graf von Arnim-Schlagenthin. She became known as “Elizabeth”, the name she used in publishing Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898), and she remained widely known as Elizabeth von Arnim, although the Library of Congress catalogues her as Mary Annette (Beauchamp), Countess von Arnim. She was a widow when she married BR’s brother, Frank, on 11 February 1916. The marriage was quickly in difficulty; she left it for good in March 1919, but they were never divorced and she remained Countess Russell (becoming Dowager Countess after Frank’s death in 1931).

Eva Kyle

Eva Kyle ran a typing service. She did work for the No-Conscription Fellowship and took BR’s dictation of his book, Roads to Freedom, in the early months of 1918. He annotated a letter from her: “She was an admirable typist but very fat. We all agreed that she was worth her weight in gold, though that was saying a great deal.” Her prison letter to him is clever and amusing. She typed his major prison writings and apologized for the amount of the invoice when he emerged.

Evelyn Whitehead

Evelyn (Willoughby-Wade) Whitehead (1865–1961). Educated in a French convent, she married Alfred North Whitehead in 1891. Her suffering, during an apparent angina attack, inspired BR’s profound sympathy and occasioned a storied episode which he described as a “mystic illumination” (Auto. 1: 146). Through her he supported the Whitehead family finances during the writing of Principia Mathematica. During the early stages of his affair with Ottoline Morrell, she was BR’s confidante. They maintained their mutual affection during the war, despite the loss of her airman son, Eric. BR last visited Evelyn in 1950 in Cambridge, Mass., when he found her in very poor health.

Fellowship Plan

Since the upper-age limit for compulsory military service had been increased to 50 in April 1918, BR was faced with the unnerving prospect of being conscripted after his release from Brixton. Early in his imprisonment he was already wondering about his “position when I emerge from here” (Letter 9). While his conviction was still under appeal, he had broached with Clifford Allen and Gilbert Murray the possibility of avoiding military service, not by asserting his conscientious objection to it, but by obtaining accreditation of his philosophical research as work of national importance (see note to Letter 24). The Pelham Committee, set up by the Board of Trade in March 1916, was responsible for the designation of essential occupations and recommending to the local tribunals, who adjudicated claims for exemption from military service, that C.O.s be considered for such positions. BR reasoned to Murray on 2 April that a dispensation to practise philosophy (as opposed to working outside his profession), would enable to him to “avoid prison without compromise” — i.e., of his political and moral opposition to conscription (BRACERS 52367). Although BR intended to withdraw from political work, he told Murray two days later, he would not promise to abstain from peace campaigning (BRACERS 52369). It should be noted that C.O.s who accepted alternative service in special Home Office camps were expressly prohibited from engaging in pacifist activities (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 231).

BR was far from sanguine about the prospect of success before a local tribunal. But he came to think (by early June) that his chances would be improved if his academic supporters interceded directly with the Minister of National Service, Sir Auckland Geddes. In addition, he calculated that such entreaties would be more effective if those acting on his behalf could secure and even endow a fellowship for him and thereby have “something definite to put before Geddes” (Letter 12; see also Letters 15 and 19). BR definitely wanted to rededicate himself to philosophy and would have welcomed a new source of income from academic employment (see Letter 22). But the “financial aspect was quite secondary”, he reminded Frank on 24 June (Letter 27); he was interested in the fellowship plan primarily as a safeguard against being called up, for teachers over 45 were not subject to the provisions of the recently amended Military Service Act. In the same letter, however, BR told his brother that “I wish it <the plan> dropped” on account of reservations expressed to him in person by Wildon Carr and A.N. Whitehead (see also Letter 31), two philosophers whom he respected but who seemed to doubt whether BR’s financial needs were as great as they appeared (see note to Letter 102).

Yet BR’s retreat was only temporary. On 8 August, he expressed to Ottoline a renewed interest in the initiative, and a few days later, she, her husband and Gladys Rinder met in London to discuss the matter. As Ottoline reported to BR, “we all felt that it was useless to wait for others to start and we decided that P. and I should go and see Gilbert M. and try and get him to work it with the Philosophers” (11 Aug. 1918, BRACERS 114754). BR probably wanted Murray to spearhead this lobbying (see also Letters 65 and 70) because of his political respectability and prior success in persuading professional philosophers to back an appeal to the Home Secretary for BR’s sentence to be served in the first division (see Letter 6). Murray did play a leading role but not until early the following month, when BR was anxious for the fellowship plan to succeed as his release date neared. The scheme finally gathered momentum after a meeting between Ottoline, Rinder and Carr on 6 September 1918, at which the philosopher and educationist T. Percy Nunn, another academic supporter of BR, was also present. Within a few days Murray had drafted a statement with an appeal for funds, which was endorsed by Carr, Whitehead, Nunn, Samuel Alexander, Bernard Bosanquet, G. Dawes Hicks, A.E. Taylor and James Ward. This memorial was then circulated in confidence to philosophers and others, but only after BR’s release from Brixton. (Financial pledges had already been made by a few of BR’s friends and admirers, notably Lucy Silcox and Siegfried Sassoon.) BR’s solicitor, J.J. Withers, became treasurer of this endowment fund, the goal of which was to provide BR with £150 or £200 per annum over three years. On 30 August BR had confessed to Ottoline that he did not want an academic position “very far from London” (Letter 89) and reiterated this desire in a message to Murray communicated by Rinder (Letter 97). On 6 September Rinder (BRACERS 79633) hinted that she already knew where the appointment would be, but there are no other indications that a particular establishment had been decided upon. Ultimately, no affiliation was contemplated for BR, so the memorial stated, because “in the present state of public feeling no ordinary university institution is likely to be willing to employ him as a teacher” (copy in BRACERS 56750). The circular talked instead of a “special Lectureship”, and the £100 BR received from the fund early in 1919 was explicitly issued as payment for lectures (on “The Analysis of Mind”; see syllabus, in Papers 9: App. III.1) that he would deliver that spring. BR’s solicitor also informed him that provision existed to pay him a further £100 for an autumn lecture course (see syllabus, ibid.: App. III.2), and Withers anticipated that these arrangements might “last two or three years” (2 Jan. 1919, BRACERS 81764). BR had already obtained a £50 gift from the fund in November 1918. Somewhat ironically, the critical importance of a teaching component to the fellowship plan — as insurance against conscription — was reduced by the authorities hesitating to hound BR any further after his imprisonment, and all but nullified by the end of the war a few weeks later. (There were no fresh call-ups, but the last of the C.O.s already in prison were not released until August 1919, and conscription remained in effect until April 1920.)

Francis Meynell

Francis Meynell (1891–1975; knighted 1946), journalist, publisher, and graphic designer, was one of BR’s colleagues in the No-Conscription Fellowship. After being called up in 1916 and refusing to serve, he was detained in military custody at Hounslow Barracks; he was released after a twelve-day hunger strike (see Letter 24). In 1915 Meynell founded the Pelican Press as a publishing outlet for peace propaganda and was also a contributing editor for the Independent Labour Party’s resolutely anti-war Daily Herald. BR evidently respected the political tenacity of Meynell, who remembered being told by him that “I like you … because in spite of your spats there is much of the guttersnipe about you” (Francis Meynell, My Lives [London: The Bodley Head, 1971], p. 89).

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).

George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

George Allen & Unwin Ltd., founded by Stanley Unwin in 1914, was BR’s chief British publisher, had published Principles of Social Reconstruction in 1916, and was in the process of publishing Roads to Freedom (1918) while BR was in Brixton.

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Governor of Brixton Prison / Carleton Haynes

Captain Carleton Haynes (1858–1945), the Governor of Brixton Prison in 1918, was a retired army officer and a cousin of BR’s acquaintance, the radical lawyer and author E.S.P. Haynes. In March 1919 BR sent Haynes, in jest, a copy (now in the Russell Archives) of his newly published Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy — so that the governor’s collection of works written by inmates while under his charge would “not ... be incomplete” (BRACERS 123167).

H. Wildon Carr

Herbert Wildon Carr (1857–1931), Professor of Philosophy at King’s College, London, from 1918 and Visiting Professor at the University of Southern California from 1925. Carr came to philosophy late in life after a lucrative career as a stockbroker. His philosophy was an idiosyncratic amalgam of Bergsonian vitalism and Leibnizian monadology, which, he thought, was supported by modern biology and the theory of relativity. He wrote books on Bergson and Leibniz at opposite ends of his philosophical career and a book on relativity in the middle. His philosophy would have made him an unlikely ally of BR’s, but it was Carr who organized BR’s two courses of public lectures, on philosophy of mathematics and the philosophy of logical atomism, which brought BR back to philosophy and improved his finances in 1917–18. Carr had great administrative talents, which he employed also on behalf of the Aristotelian Society during his long association with it. He was its president in 1916–18 and continued to edit its Proceedings until 1929.

H.A. Hollond

Captain Henry Arthur Hollond (1884–1974), in civilian life, was a legal scholar who had become friendly with BR after being elected a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1909. The two men also briefly shared rooms at Harvard in spring 1914, where Hollond was studying law and BR was lecturing on logic and epistemology (see SLBR 1: 481). A few months later Hollond enlisted and became a staff officer at British headquarters in France. He remained a Fellow of Trinity for the rest of his life and later served the college as Dean and Vice-Master, as well as holding a university professorship in English law (1943–50). BR’s presumption that Hollond would advocate for him may have been misplaced. When he returned to Trinity in 1944, BR was deeply hurt after seeing a letter indicating that Hollond had not supported him when he was dismissed from his lectureship at the college in 1916. He stewed over this early betrayal until finally initiating a break from Hollond in 1964 (BRACERS 7637).

J.J. Withers

John James Withers (1863–1939; knighted 1929) was senior partner in the prominent City law firm that bore his name and was located near the legal district of the Temple. Specialists in family law (although clearly not to the exclusion of other services), Withers & Co. acted for both BR and his brother for many years. In 1926 Withers was elected unopposed as Conservative M.P. for Cambridge University and held the seat for the remainder of his life.

Katherine Mansfield

Katherine Mansfield (1888–1923), pseudonym of Kathleen Mansfield Beauchamp, New Zealand-born short-story writer. After studying music in her native country, Mansfield moved to London in 1908, married George Bowden, a music teacher, whom she left after a few days, the marriage unconsummated. She was at the time pregnant from a previous affair. Her experiences in Bavaria, where the child was stillborn, became the background for her first collection of stories, In a German Pension (1911), most of which had been previously published in A.R. Orage’s journal, The New Age. In 1911 she met J. Middleton Murry, who fell quickly under her spell and with whom she was to be associated until the end of her life, though they frequently lived independently and married only in 1918. Her health had long been fragile, and in 1918 she was diagnosed with the tuberculosis which eventually killed her. BR met her in 1916 when she was living in Gower Street, near BR’s brother’s house in Gordon Square. For a short time they had an intimate friendship, but not an affair. BR found her talk, especially about what she planned to write, “marvellous, much better than her writing”. But “when she spoke about people she was envious, dark and full of alarming penetration in discovering what they least wished known.” She spoke in this vein of Ottoline Morrell. BR listened but in the end “believed very little of it” and, after that, saw Mansfield no more (Auto. 2: 27). Main biography: Antony Alpers, The Life of Katherine Mansfield (New York: Viking, 1980).

Lytton Strachey

Lytton Strachey (1880–1932), biographer, reviewer and a quintessential literary figure of the Bloomsbury Group. He is best known for his debunking portraits of Cardinal Manning, Florence Nightingale, Dr. Arnold and General Gordon, published together as Eminent Victorians (London: Chatto & Windus, 1918; Russell’s library), which BR read in Brixton with great amusement as well as some critical reservations (see Letter 7). Although Strachey was homosexual, he and the artist Dora Carrington were devoted to each other and from 1917 lived together in Tidmarsh, Berkshire. BR had become acquainted with the somewhat eccentric Strachey, a fellow Cambridge Apostle, while his slightly younger contemporary was reading history at Trinity College. He admired Strachey’s literary gifts, but doubted his intellectual honesty. Almost three decades later BR fleshed out the unflattering thumbnail of Strachey drawn for Ottoline in Letter 7, in a “Portrait from Memory” for BBC radio. Strachey was “indifferent to historical truth”, BR alleged in that broadcast, “and would always touch up the picture to make the lights and shades more glaring and the folly or wickedness of famous people more obvious” (The Listener 48 [17 July 1952]: 98). Main biography: Michael Holroyd, Lytton Strachey: a Critical Biography, 2 vols. (London: Heinemann, 1967–68).

Mary Hamilton

Mary Agnes (“Molly”) Hamilton (1882–1966), socialist peace campaigner, novelist and journalist, became one of the first members of the Union of Democratic Control in August 1914. She was acquainted with both Ottoline and the pacifist literary circle around her at Garsington Manor. After the war Hamilton served for a time as deputy-editor of the Independent Labour Party weekly, The New Leader, and was briefly (1929–31) Labour M.P. for Blackburn.

Maurice Elvey

Maurice Elvey (1887–1967) was a prolific film director (of silent pictures especially) and enjoyed a very successful career in that industry lasting many decades. Born William Seward Folkard into a working-class family, Elvey changed his name around 1910, when he was acting. He directed his first film, The Fallen Idol, in 1913. By 1917, when he directed Colette in Hindle Wakes, he had married for a second time — to a sculptor, Florence Hill Clarke — his first marriage having ended in divorce. Elvey and Colette had an affair during the filming of Hindle Wakes, beginning in September 1917, which caused BR great anguish. In addition to his feeling of jealousy during his imprisonment, BR was worried over the rumour that Elvey was carrying a dangerous sexually transmitted disease. (See BR, “My First Fifty Years”, RA1 210.007050–fos. 127b, 128, and Monk, 2: 507). Colette later maintained that Elvey cleared himself (“Letters to Bertrand Russell from Constance Malleson, 1916–1969”, p. 154, typescript, RA). BR removed the allegation from the Autobiography as published (see 2: 37), but he remained fearful. After Elvey’s long-lost wartime film about the life of Lloyd George was rediscovered and restored in the 1990s, it premiered to considerable acclaim (see Letter 87, note 12).

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

Siegfried Sassoon

Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967), soldier awarded the MC and anti-war poet. Ottoline had befriended him in 1916, and the following year, when Sassoon refused to return to his regiment after being wounded, she and BR helped publicize this protest, which probably saved him from a court martial. BR even assisted Sassoon in revising his famous anti-war statement, which was read to the House of Commons by a Liberal M.P. on 30 July 1917. Sassoon’s actions were an embarrassment to the authorities, for he was well known as both a poet and a war hero. Unable to hush the case up, the government acted with unexpected subtlety and declared Sassoon to be suffering from shell-shock and sent him to Craiglockhart War Hospital for Officers, near Edinburgh. After a period of recuperation in Scotland overseen by military psychiatrist Capt. W.H.R. Rivers, Sassoon decided to return to the Front (see Jean Moorcroft Wilson, Siegfried Sassoon: Soldier, Poet, Lover, Friend [New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2014]). He was again wounded in July 1918 and was convalescing in Britain during some of BR’s imprisonment. Although each admired the other’s stand on the war, BR and Sassoon were never close in later years. Yet Sassoon did pledge £50 to the fellowship plan fund (see BRACERS 114758), and decades later he donated a manuscript in support of BR’s International War Crimes Tribunal (see BRACERS 79066).

Sir Auckland Geddes

Sir Auckland Geddes (1879–1954; 1st Baron Geddes, 1942) was returned unopposed as Conservative M.P. for Basingstoke in a by-election held in October 1917. Before this entry into civilian public life, he held the rank of Brigadier-General as director of recruiting at the War Office. He was an ardent champion of conscription even in peacetime and had a long-standing interest in the military, which he expressed before the war as a volunteer medical officer in the British Army Reserve. He had studied medicine and was Professor of Anatomy at McGill University, Montreal, when the outbreak of war prompted an immediate return to Britain in order to enlist. After a riding accident rendered Geddes unfit for front-line duties, he became a staff officer in France with a remit covering the supply and deployment of troops. He performed similar duties at the War Office until his appointment in August 1917 as a Minister of National Service with broad powers over both military recruitment and civilian labour. Geddes held two more Cabinet positions in Lloyd George’s post-war Coalition Government before his appointment in 1920 as British Ambassador to the United States. After returning from Washington on health grounds three years later, Geddes embarked upon a successful business career, becoming chairman in 1925 of the Rio Tinto mining company. See Oxford DNB.