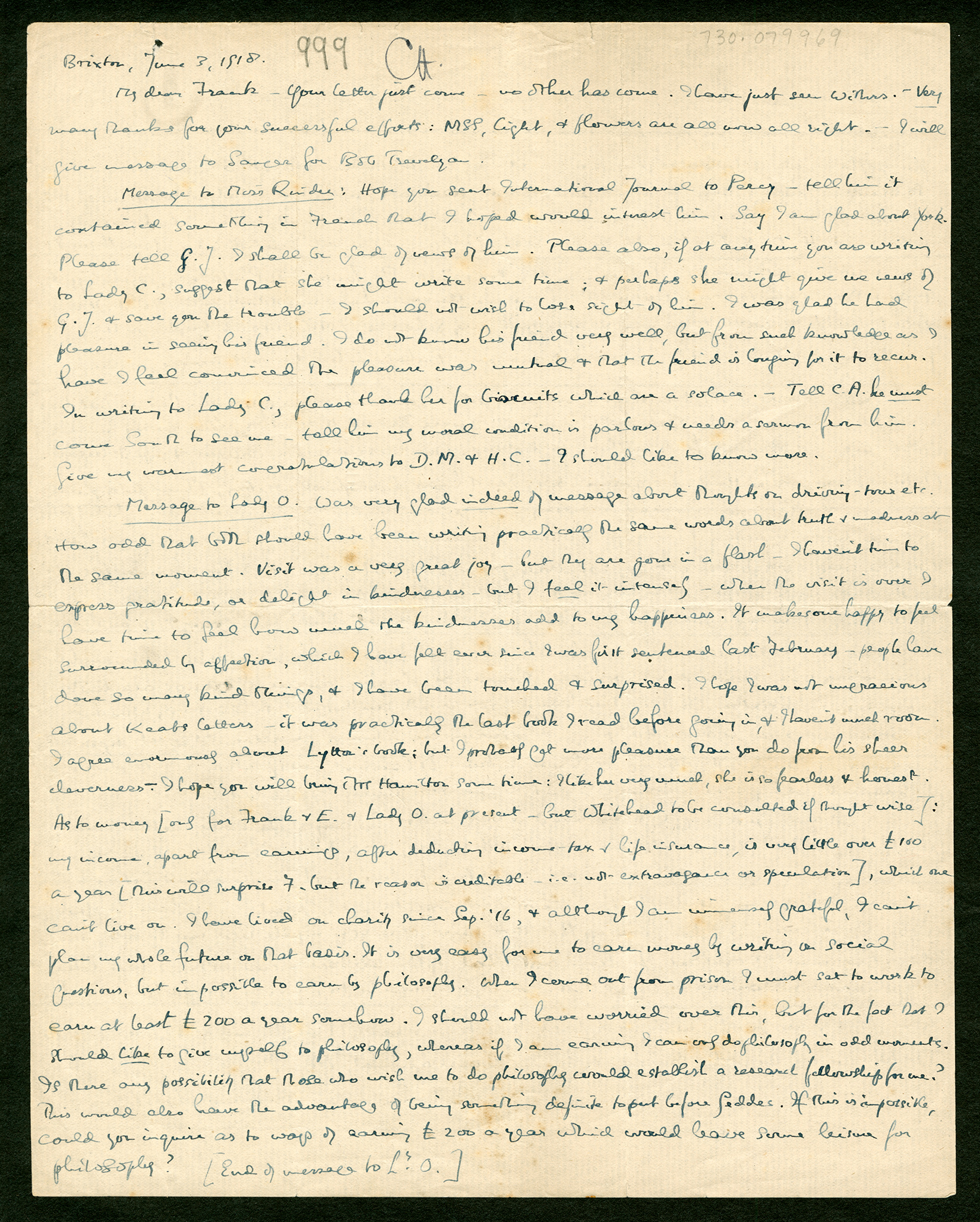

Brixton Letter 12

BR to Frank Russell

June 3, 1918

- ALS

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-12Auto. 2: 86

BRACERS 46917

My dear Frank

Your letter2 just come — no other has come. I have just seen Withers. — Very many thanks for your successful efforts: MSS, light, and flowers are all now all right. — I will give message to Sanger for Bob Trevelyan.3

Message to Miss Rinder: Hope you sent International Journal to Percy — tell him it contained something in French4 that I hoped would interest him. Say I am glad about York.5 Please tell G.J. I shall be glad of news of him. Please also, if at any time you are writing to Lady C., suggest that she might write some time; and perhaps she might give me news of G.J. and save you the trouble — I should not wish to lose sight of him. I was glad he had pleasure in seeing his friend.6 I do not know his friend very well, but from such knowledge as I have I feel convinced the pleasure was mutual and that the friend is longing for it to recur. In writing to Lady C., please thank her for biscuits which are a solace. — Tell C.A. he must come South to see me — tell him my moral condition is parlous and needs a sermon from him. Give my warmest congratulations to D.M. and H.C.7 — I should like to know more.

Message to Lady O. Was very glad indeed of message about thoughts on driving-tour etc.8 How odd that both should have been writing practically the same words about truth and madness at the same moment.9 Visit was a very great joy — but they are gone in a flash — I haven’t time to express gratitude, or delight in kindnesses — but I feel it intensely — when the visit is over I have time to feel how much the kindnesses add to my happiness. It makes one happy to feel surrounded by affection, which I have felt ever since I was first sentenced last February — people have done so many kind things, and I have been touched and surprised. I hope I was not ungracious about Keats letters10 — it was practically the last book I read before going in, and I haven’t much room. I agree enormously about Lytton’s book;11 but I probably get more pleasure than you do from his sheer cleverness. — I hope you will bring Mrs Hamilton12 some time: I like her very much, she is so fearless and honest. As to money [only for Frank and E. and Lady O. at present — but Whitehead to be consulted if thought wise]: my income, apart from earnings,13 after deducting income tax and life insurance, is very little over £100 a year [this will surprise F. but the reason is creditable — i.e. not extravagance or speculation],14 which one can’t live on. I have lived on charity since Sep. ’16, and although I am immensely grateful, I can’t plan my whole future on that basis. It is very easy for me to earn money by writing on social questions, but impossible to earn by philosophy.15 When I come out from prison I must set to work to earn at least £200 a year somehow. I should not have worried over this, but for the fact that I should like to give myself to philosophy, whereas if I am earning I can only do philosophy in odd moments. Is there any possibility that those who wish me to do philosophy could establish a research fellowship for me? This would also have the advantage of being something definite to put before Geddes. If this is impossible, could you inquire as to ways of earning £200 a year which would leave some leisure for philosophy? [End of message to Ly. O.]

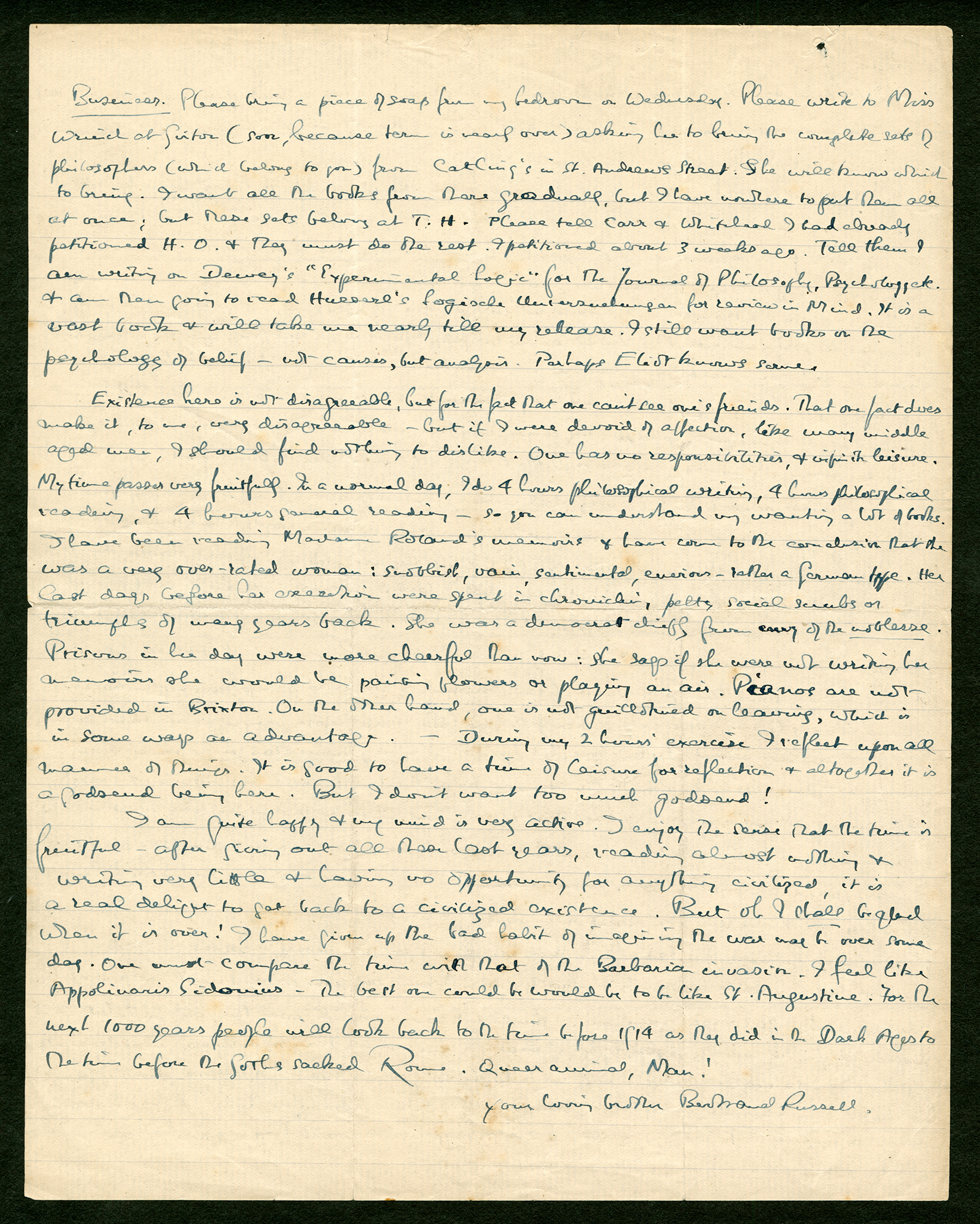

Business. Please bring a piece of soap from my bedroom on Wednesday. Please write to Miss Wrinch at Girton (soon, because term is nearly over) asking her to bring the complete sets of philosophers (which belong to you) from Catling’s in St. Andrews Street.16 She will know which to bring. I want all the books from there gradually, but I have nowhere to put them all at once; but these sets belong at T.H. Please tell Carr and Whitehead I had already petitioned H. O.17 and they must do the rest. I petitioned about 3 weeks ago. Tell them I am writing on Dewey’s Experimental Logic18 for the Journal of Philosophy, Psychology etc. and am then going to read Husserl’s Logische Untersuchungen for review in Mind.19 It is a vast book and will take me nearly till my release. I still want books on the psychology of belief — not causes, but analysis. Perhaps Eliot knows some.20

Existence here is not disagreeable, but for the fact that one can’t see one’s friends. That one fact does make it, to me, very disagreeable — but if I were devoid of affection, like many middle aged men, I should find nothing to dislike. One has no responsibilities, and infinite leisure. My time passes very fruitfully. In a normal day, I do 4 hours philosophical writing, 4 hours philosophical reading, and 4 hours general reading — so you can understand my wanting a lot of books. I have been reading Madame Roland’s memoirs21 and have come to the conclusion that she was a very over-rated woman: snobbish, vain, sentimental, envious — rather a German type. Her last days before her execution were spent in chronicling petty social snubs or triumphs of many years back. She was a democrat chiefly from envy of the noblesse. Prisons in her day were more cheerful than now: she says if she were not writing her memoirs she would be painting flowers or playing an air. Pianos are not provided in Brixton. On the other hand, one is not guillotined on leaving, which is in some ways an advantage. — During my two hours’ exercise I reflect upon all manner of things. It is good to have a time of leisure for reflection and altogether it is a godsend being here. But I don’t want too much godsend!

I am quite happy and my mind is very active. I enjoy the sense that the time is fruitful — after giving out all these last years, reading almost nothing and writing very little and having no opportunity for anything civilized, it is a real delight to get back to a civilized existence. But oh I shall be glad when it is over! I have given up the bad habit of imagining the war may be over some day. One must compare the time with that of the Barbarian invasion. I feel like Appolinaris Sidonius22 — the best one could be would be to be like St. Augustine.23 For the next 1000 years people will look back to the time before 1914 as they did in the Dark Ages to the time before the Goths sacked Rome. Queer animal, Man!

Your loving brother

Bertrand Russell.

- 1

[document] The document was edited from the signed original in BR’s handwriting in the Russell Archives. On thin, ruled, laid paper, it consists of a single sheet filled on both sides. It was folded once horizontally and twice vertically. Prisoners’ correspondence was subject to the Governor’s approval. This letter has “CH” (for Carleton Haynes) handwritten at the top, making it an “official” letter, despite not having been written on the blue correspondence form of the prison system. The letter was extracted in BR’s Autobiography, 2: 86.

- 2

your letterFrank Russell’s letter of 31 May 1918 (BRACERS 46916).

- 3

message to Sanger for Bob Trevelyan BR had placed C.P. Sanger, the multi-talented barrister, second on his “extra” list of preferred visitors (see Letter 5), and he probably intended to use him as a courier of this (unfortunately missing) communication to another old Cambridge friend, the poet and translator Robert Trevelyan (1872–1951).

- 4

International Journal to Percy … something in French BR had secreted a short letter (Letter 11) to Colette inside an issue of a periodical, probably The International Journal of Ethics. (See the contents of the April 1918 issue, which could have interested BR and at 150 pages was thick enough to conceal a letter; he had contributed to this periodical as recently as July 1916 [B&R C16.15].) She appears not to have received the letter. BR identified “Percy” in a note at BRACERS 116566: “Another pseudonym for Colette.” “Percy” was a nickname used by Colette’s family and which she continued to use in family correspondence decades later.

- 5

York Early in BR’s incarceration Colette had been in York (and Manchester and Scarborough), touring with a theatre company, playing the role of Mabel in Phyl (author unknown).

- 6

friend “G.J. is one of Colette’s pseudonyms. The friend I do not know very well is myself.” (BR’s note at BRACERS 93478.)

- 7

warmest congratulations to D.M. and H.C.Dorothy Mackenzie had been the fiancée of Lieut. A. Graeme West, a soldier who had written to BR from the Front about politics (see his letters in Auto. 2: 71–2, 76). The Diary of a Dead Officer, a collection of his letters and memorabilia edited by Cyril Joad, was published in 1918 by Allen & Unwin. After West was killed in action in April 1917, BR got to know both Mackenzie and the man she would soon marry, “H.C.”, Hilderic Cousens (1896–1962), a C.O. who after the war became a schoolteacher of Latin and Greek. In a letter written decades later, Dorothy Cousens reminded BR of how she and her late husband had become acquainted: “Long ago in 1918 you contrived for Hilderic and me to work for you in the B<ritish> Museum and get to know each other” (13 March 1962, BRACERS 76030).

- 8

driving-tour In a message conveyed in Gladys Rinder’s letter to BR of 25 May 1918, Ottoline gave a brief account of her “short driving tour round the country” with Philip Morrell, and their enjoyment of the great natural beauty (BRACERS 79611). For a lengthier recollection of this journey, see R. Gathorne-Hardy, ed., Ottoline at Garsington: Memoirs of Lady Ottoline Morrell, 1915–1918 (London: Faber and Faber, 1974), pp. 247–8.

- 9

How odd that both … truth and madness at the same moment. By “both” BR meant Ottoline and himself. On 28–30? May 1918 (BRACERS 114745), Ottoline wrote: “I have been very depressed lately — for I seem to have torn the Veil off from Life — and left it all so naked and bear<sic> — sun, sun — and I have almost invited those who have not had the desire to look into the eyes of truth — but my faith always returns and I know that the residue that is Left is Sublime — and that Life altho tragic throughout — is worth it — any suffering is worth that divine something that only comes to those whose belief is beaten about by every wind that can blow.” BR had written in Letter 9: “The contrast with Bates is remarkable: one sees how our generation, in comparison, is a little mad, because it has allowed itself glimpses of the truth, and the truth is spectral, insane, ghastly: the more men see of it, the less mental health they retain. The Victorians (dear souls) were sane and successful because they never came anywhere near truth. But for my part I would rather be mad with truth than sane with lies.”

- 10

Keats lettersLetters of John Keats to His Family and Friends, ed. Sidney Colvin (London: Macmillan, 1891; Russell’s library).

- 11

agree enormously about Lytton’s book Ottoline was herself agreeing with BR’s defence of the Victorians (and his attack on Strachey) in a message delivered to her via Gladys Rinder (Letter 7). On 28 May Ottoline had provided BR with this brief critique of Eminent Victorians (1918): “I admire it and think it very good but it hurts me, hurts me to feel the smile and snigger that those fine men who were willing to be thought foolish for their fate — Cooke <Gordon?> in L.S. It is a book that just suits the ordinary clever men of today who are not thinking of risking anything for Faith — indeed they see no Vision — nor believe enough in anything to be carried away out of the ranks of the ‘men of the street’” (BRACERS 114745). See also Letter 27, in which BR (without hinting at the sheer enjoyment he derived from the book) expressed guarded approval of a Times editorial criticizing it.

- 12

I hope you will bring Mrs Hamilton Mary Agnes (“Molly”) Hamilton (1882–1966) was seventh on the list of possible visitors drawn up by BR for Frank in Letter 5. A socialist peace campaigner, novelist and journalist, she became one of the first members of the Union of Democratic Control in August 1914. She was acquainted with both Lady Ottoline Morrell and the pacifist literary circle around her at Garsington Manor. After the war Hamilton served for a time as deputy-editor of the Independent Labour Party weekly, The New Leader, and was briefly (1929–31) Labour M.P. for Blackburn.

- 13

my income, apart from earnings This would have included income from his marriage settlement. See note 22 in Letters 15and note 12 in102.

- 14

reason is creditable As BR told Evelyn Whitehead the previous year, he “had got into the way of giving away what I don’t earn” (BRACERS 119038).

- 15

impossible to earn by philosophy BR’s logic lectures early in the year (“The Philosophy of Logical Atomism”) produced very little income for him, as evidenced by the earnings record in his 1917–18 pocket diary. The course earned him only £10 (Papers 8: 157–8).

- 16

complete sets of philosophers … Catling’s in St. Andrews Street Catling & Son was the Cambridge auction house which had managed the public sale of possessions from BR’s rooms at Trinity College in July 1916 (see S. Turcon, “Russell Sold Up”, Russell 6 [1986]: 71–6). These goods had been distrained after BR refused to pay the £100 fine imposed by his first conviction under the Defence of the Realm Act. But friends had resolved to buy back his library — to BR’s slight regret, since he felt that his defiance had been rendered “somewhat futile” by this kindness (Auto. 2: 33). Yet he was relieved that his library — not least its “complete sets of philosophers”, to which he had attached special value at the time (BRACERS 18582) — had not been dispersed. BR reminded his brother that these volumes belonged to him, presumably because they had been part of their father’s collection. Shortly before the auction BR had also been deprived of his lectureship by the Trinity College Council and was thereby compelled to vacate his rooms. BR had stored these books, and possibly other possessions, at Catling & Son rather than at his London flat (which was often sublet) or either of his brother’s homes.

- 17

petitioned H.O. See Letter 4. Frank had written on 31 May: “With regard to Dr. Carr and Professor Whitehead the Home Office suggest that you should definitely petition them asking for an extra visit once a week for either or both these gentlemen, setting out clearly that it is for professional reasons connected with your work” (BRACERS 46916).

- 18

I am writing on Dewey’s Experimental Logic Published as “Professor Dewey’s Essays in Experimental Logic”, The Journal of Philosophy, Psychology and Scientific Methods 16 (2 Jan. 1919): 5–26 (B&R C19.02); 16 in Papers 8, it was a surprisingly conciliatory defence of his own views against Dewey’s criticism. BR completed his 10,000 word review by early June (see Letter 15). His library holds the copy of Essays in Experimental Logic (Chicago: U. of Chicago P., 1916) that he read and annotated during his imprisonment.

- 19

read Husserl’s Logische Untersuchungen for review in Mind Logische Untersuchungen, 2 vols., 2nd ed. (Halle: Max Niemeyer, 1913 [part 1 of vol. 2]). While in prison BR did read the first volume of this “vast book” by the German philosopher and founder of phenomenology, Edmund Husserl (1859–1938), but he never did write a review of it. The second edition of the second volume was in two parts, and the second part did not appear until 1921. (See Letter 15.) Nikolay Milkov, “Edmund Husserl and Bertrand Russell, 1905–1918” (in Peter Stone, ed., Bertrand Russell’s Life and Legacy [Wilmington, DE: Vernon P., 2017], p. 84) discusses BR’s intention to write a review, but he cites only one letter (Letter 15) from BR and none to him.

- 20

Perhaps Eliot knows some Frank evidently passed on BR's request, for on 5 July Frank quoted a message from Eliot to BR (BRACERS 116765): “Would Brentano’s ‘Classification of Psychical Phenomena’ interest you? I have it.” Since there was then no English translation, he would have meant Brentano’s Von der Klassifikation der psychischen Phänomene [Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, 1911]). See Letter 34, note 6.

- 21

I have been reading Madame Roland’s memoirs Possibly The Private Memoirs of Madame Roland, ed. Edward Gilpin Johnson (London: Grant Richards, 1901), the reissue of an English translation first published in London only two years after the prominent Girondin (née Marie-Jeanne Philipon, 1754–1793), perished in the Terror. This exculpatory account of her moderate political faction’s role in the French Revolution was hastily written during the five months’ imprisonment that preceded her execution by guillotine.

- 22

One must compare ... Barbarian invasion … Appolinaris Sidonius The poems and letters of Gallo-Roman aristocrat Sidonius Apollinaris (c.430–489) shed light on the traditions of both early Christianity and late Antiquity, which were alike threatened in the fifth century by incursions of Germanic tribes into the Western Roman Empire. As Bishop of Auvergne (Clermont) in 474, Sidonius Apollinaris mounted a final, doomed defence of Roman Auvergne against the invading Visigoths.

- 23

the best ... like St. Augustine St. Augustine of Hippo (354–430) wrote The City of God as the entire Western Roman Empire stood threatened by Germanic invaders; he died while the port-city in Roman Carthage, of which he was bishop, was under siege by the Vandals. Although the main purpose of his most famous theological treatise was to challenge those blaming the rise of Christianity for the decline of Rome, its truly valuable legacy, according to BR in an eloquent aside written in 1946, was “to sum up the best elements of the perishing civilization and to give them a lasting ideal form, making some kind of beacon of light in the long darkness. This is a great task, and I hope there is someone in our age who can accomplish it” (Papers 11: 82). During the Second World War BR was again inclined to compare himself to St. Augustine (see SLBR 2: 379).

A.N. Whitehead

Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947), Cambridge-educated mathematician and philosopher. From 1884 to 1910 he was a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, and lecturer in mathematics there; from 1911 to 1924 he taught in London, first at University College and then at the Imperial College of Science and Technology; in 1924 he took up a professorship in philosophy at Harvard and spent the rest of his life in America. BR took mathematics courses with him as an undergraduate, which led to a lifelong friendship. Whitehead’s first major work was A Treatise on Universal Algebra (1898), which treated selected mathematical theories as “systems of symbolic reasoning”. Like BR’s The Principles of Mathematics (1903), it was intended as the first of two volumes; but in 1900 he and BR discovered Giuseppe Peano’s work in symbolic logic, and each decided to set aside his projected second volume to work together on a more comprehensive treatment of mathematics using Peano’s methods. The result was the three volumes of Principia Mathematica (1910–13), which occupied the pair for over a decade. After Principia was published, Whitehead’s interests, like BR’s, turned to the empirical sciences and, finally, after his move to America, to pure metaphysics. See Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: the Man and His Work, 2 vols. (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins U. P., 1985–90).

Annotations by BR

In the late 1940s, when BR was going through his archives, and in the 1950s when he was revising his Autobiography, he would occasionally annotate letters. He did this to sixteen of the Brixton letters. Links to them are gathered here for convenient access to these new texts. In the annotations to the letters they are always followed by “(BR’s note.)”

Letter 2, note 5 happy.

5, note 6 congratulations to G.J.

9, note 28 bit of Girondin history.

12, note 6 friend.

15, note 2 (the letter in general).

20, note 7 G.J.

31, note 3 Dr’s treatment.

40, notes 9, 10 Ld. G.L.G, Lady B’s.

44, note 14 S.S.

48, note 48 Mother Julian’s Bird.

57, notes 13, 16 Ld. Granville’s to Ly. B., bless that Dr. … seat of intellect.

70, note 15 Mrs Scott.

73, note 12 E.S.P. Haynes.

76, note 4 Cave.

85, note 2 Marsh on Rupert.

102, notes 23, 28 Woolley, K. Lonsdale.

General Annotations

Brett note from Auto. 2: 93

Cousens note from Auto. 2: 71

Kyle note with her letters to BR

Rinder note from Auto. 2: 88n.

Silcox note on BRACERS 80365

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

C.P. Sanger

Charles Percy Sanger (1871–1930) and BR remained close friends after their first-year meeting at Trinity College, to which both won mathematics scholarships and where their brilliance was almost equally rated. They were elected to the Cambridge Apostles and obtained their fellowships at the same time. After being called to the Bar, Sanger became an erudite legal scholar and was an able economist with great facility in languages as well. BR fondly recalled his “perfect combination of penetrating intellect and warm affection” (Auto. 1: 57).

Clifford Allen

(Reginald) Clifford Allen (1889–1939; Baron Allen of Hurtwood, 1932) was a socialist politician and publicist who joined the Cambridge University Fabian Society while studying at Peterhouse College (1908–11). After graduating he became active in the Independent Labour Party in London and helped establish a short-lived labour newspaper, the Daily Citizen. During the war Allen was an inspiring and effective leader of the C.O. movement as chairman of the No-Conscription Fellowship, which he co-founded with Fenner Brockway in November 1914. Court-martialled and imprisoned three times after his claim for absolute exemption from war service was rejected, Allen became desperately ill during his last spell of incarceration. He was finally released from the second division of Winchester Prison on health grounds in December 1917, but not before contracting the tuberculosis with which he was finally diagnosed in September 1918. He was dogged by ill health for the rest of his life. BR had enormous affection and admiration for Allen (e.g., 68 in Papers 13, 46 in Papers 14), a trusted wartime political associate. From February 1919 until March 1920 he even shared Allen’s Battersea apartment. A close friendship was soured, however, by Allen’s rejection of BR’s unforgiving critique of the Bolshevik regime, which both men witnessed at first hand with the British Labour Delegation to Russia in May 1920 (see Papers 15: 507). Yet Allen was far from revolutionary himself and did not even identify with the left wing of the ILP (which he chaired in the early 1920s). He was elevated to the peerage as a supporter of Ramsay MacDonald’s National Government, an administration despised by virtually the entire labour movement. Although Allen’s old intimacy with BR was never restored after the Russia trip, any lingering estrangement did not inhibit him from enrolling his daughter, Joan Colette (“Polly”) at the Russells’ Beacon Hill School.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.

Dorothy Cousens

Dorothy Cousens (née Mackenzie) had been the fiancée of Graeme West, a soldier who had written to BR from the Front about politics. The Diary of a Dead Officer, a collection of his letters and memorabilia edited by Cyril Joad, was published in 1918 by Allen & Unwin. BR got to know Mackenzie after West was killed in action in April 1917 (she, “on the news of his death, became blind for three weeks” [BR’s note, Auto. 2: 71]) and provided some work for her and the man she married, Hilderic Cousens. Decades later she explained to K. Blackwell how she knew BR: “I had a break-down when most of my generation were either killed or in prison and Bertrand Russell was kind and helped me back to sanity” (29 July 1978, BRACERS 121877). She donated Letter 63 and a much later handwritten letter (BRACERS 55813), on the death of Hilderic, to the Russell Archives.

Dorothy Wrinch

Dorothy Maud Wrinch (1894–1976), mathematician, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. She studied mathematics and philosophy at Girton College, Cambridge, and came under BR’s influence in her second year when she took his course on mathematical logic. She taught mathematics at University College, London, 1918–21, and then at Oxford, 1922–30. Her first publications were in mathematical logic and philosophy, and during the 1920s she wrote on the philosophy of science. But in the 1930s her interests turned to mathematical biology and crystallography, and in 1935 she moved to the United States on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship and remained there for the rest of her life. Unfortunately, as a biologist she is best known for a long and stubborn controversy with Linus Pauling about the structure of proteins in which he was right and she was wrong. See Marjorie Senechal, I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science (New York: Oxford U. P., 2013). Chapter 7 is devoted to Wrinch’s interactions with BR in Brixton.

Evelyn Whitehead

Evelyn (Willoughby-Wade) Whitehead (1865–1961). Educated in a French convent, she married Alfred North Whitehead in 1891. Her suffering, during an apparent angina attack, inspired BR’s profound sympathy and occasioned a storied episode which he described as a “mystic illumination” (Auto. 1: 146). Through her he supported the Whitehead family finances during the writing of Principia Mathematica. During the early stages of his affair with Ottoline Morrell, she was BR’s confidante. They maintained their mutual affection during the war, despite the loss of her airman son, Eric. BR last visited Evelyn in 1950 in Cambridge, Mass., when he found her in very poor health.

Fellowship Plan

Since the upper-age limit for compulsory military service had been increased to 50 in April 1918, BR was faced with the unnerving prospect of being conscripted after his release from Brixton. Early in his imprisonment he was already wondering about his “position when I emerge from here” (Letter 9). While his conviction was still under appeal, he had broached with Clifford Allen and Gilbert Murray the possibility of avoiding military service, not by asserting his conscientious objection to it, but by obtaining accreditation of his philosophical research as work of national importance (see note to Letter 24). The Pelham Committee, set up by the Board of Trade in March 1916, was responsible for the designation of essential occupations and recommending to the local tribunals, who adjudicated claims for exemption from military service, that C.O.s be considered for such positions. BR reasoned to Murray on 2 April that a dispensation to practise philosophy (as opposed to working outside his profession), would enable to him to “avoid prison without compromise” — i.e., of his political and moral opposition to conscription (BRACERS 52367). Although BR intended to withdraw from political work, he told Murray two days later, he would not promise to abstain from peace campaigning (BRACERS 52369). It should be noted that C.O.s who accepted alternative service in special Home Office camps were expressly prohibited from engaging in pacifist activities (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 231).

BR was far from sanguine about the prospect of success before a local tribunal. But he came to think (by early June) that his chances would be improved if his academic supporters interceded directly with the Minister of National Service, Sir Auckland Geddes. In addition, he calculated that such entreaties would be more effective if those acting on his behalf could secure and even endow a fellowship for him and thereby have “something definite to put before Geddes” (Letter 12; see also Letters 15 and 19). BR definitely wanted to rededicate himself to philosophy and would have welcomed a new source of income from academic employment (see Letter 22). But the “financial aspect was quite secondary”, he reminded Frank on 24 June (Letter 27); he was interested in the fellowship plan primarily as a safeguard against being called up, for teachers over 45 were not subject to the provisions of the recently amended Military Service Act. In the same letter, however, BR told his brother that “I wish it <the plan> dropped” on account of reservations expressed to him in person by Wildon Carr and A.N. Whitehead (see also Letter 31), two philosophers whom he respected but who seemed to doubt whether BR’s financial needs were as great as they appeared (see note to Letter 102).

Yet BR’s retreat was only temporary. On 8 August, he expressed to Ottoline a renewed interest in the initiative, and a few days later, she, her husband and Gladys Rinder met in London to discuss the matter. As Ottoline reported to BR, “we all felt that it was useless to wait for others to start and we decided that P. and I should go and see Gilbert M. and try and get him to work it with the Philosophers” (11 Aug. 1918, BRACERS 114754). BR probably wanted Murray to spearhead this lobbying (see also Letters 65 and 70) because of his political respectability and prior success in persuading professional philosophers to back an appeal to the Home Secretary for BR’s sentence to be served in the first division (see Letter 6). Murray did play a leading role but not until early the following month, when BR was anxious for the fellowship plan to succeed as his release date neared. The scheme finally gathered momentum after a meeting between Ottoline, Rinder and Carr on 6 September 1918, at which the philosopher and educationist T. Percy Nunn, another academic supporter of BR, was also present. Within a few days Murray had drafted a statement with an appeal for funds, which was endorsed by Carr, Whitehead, Nunn, Samuel Alexander, Bernard Bosanquet, G. Dawes Hicks, A.E. Taylor and James Ward. This memorial was then circulated in confidence to philosophers and others, but only after BR’s release from Brixton. (Financial pledges had already been made by a few of BR’s friends and admirers, notably Lucy Silcox and Siegfried Sassoon.) BR’s solicitor, J.J. Withers, became treasurer of this endowment fund, the goal of which was to provide BR with £150 or £200 per annum over three years. On 30 August BR had confessed to Ottoline that he did not want an academic position “very far from London” (Letter 89) and reiterated this desire in a message to Murray communicated by Rinder (Letter 97). On 6 September Rinder (BRACERS 79633) hinted that she already knew where the appointment would be, but there are no other indications that a particular establishment had been decided upon. Ultimately, no affiliation was contemplated for BR, so the memorial stated, because “in the present state of public feeling no ordinary university institution is likely to be willing to employ him as a teacher” (copy in BRACERS 56750). The circular talked instead of a “special Lectureship”, and the £100 BR received from the fund early in 1919 was explicitly issued as payment for lectures (on “The Analysis of Mind”; see syllabus, in Papers 9: App. III.1) that he would deliver that spring. BR’s solicitor also informed him that provision existed to pay him a further £100 for an autumn lecture course (see syllabus, ibid.: App. III.2), and Withers anticipated that these arrangements might “last two or three years” (2 Jan. 1919, BRACERS 81764). BR had already obtained a £50 gift from the fund in November 1918. Somewhat ironically, the critical importance of a teaching component to the fellowship plan — as insurance against conscription — was reduced by the authorities hesitating to hound BR any further after his imprisonment, and all but nullified by the end of the war a few weeks later. (There were no fresh call-ups, but the last of the C.O.s already in prison were not released until August 1919, and conscription remained in effect until April 1920.)

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Governor of Brixton Prison / Carleton Haynes

Captain Carleton Haynes (1858–1945), the Governor of Brixton Prison in 1918, was a retired army officer and a cousin of BR’s acquaintance, the radical lawyer and author E.S.P. Haynes. In March 1919 BR sent Haynes, in jest, a copy (now in the Russell Archives) of his newly published Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy — so that the governor’s collection of works written by inmates while under his charge would “not ... be incomplete” (BRACERS 123167).

H. Wildon Carr

Herbert Wildon Carr (1857–1931), Professor of Philosophy at King’s College, London, from 1918 and Visiting Professor at the University of Southern California from 1925. Carr came to philosophy late in life after a lucrative career as a stockbroker. His philosophy was an idiosyncratic amalgam of Bergsonian vitalism and Leibnizian monadology, which, he thought, was supported by modern biology and the theory of relativity. He wrote books on Bergson and Leibniz at opposite ends of his philosophical career and a book on relativity in the middle. His philosophy would have made him an unlikely ally of BR’s, but it was Carr who organized BR’s two courses of public lectures, on philosophy of mathematics and the philosophy of logical atomism, which brought BR back to philosophy and improved his finances in 1917–18. Carr had great administrative talents, which he employed also on behalf of the Aristotelian Society during his long association with it. He was its president in 1916–18 and continued to edit its Proceedings until 1929.

J.J. Withers

John James Withers (1863–1939; knighted 1929) was senior partner in the prominent City law firm that bore his name and was located near the legal district of the Temple. Specialists in family law (although clearly not to the exclusion of other services), Withers & Co. acted for both BR and his brother for many years. In 1926 Withers was elected unopposed as Conservative M.P. for Cambridge University and held the seat for the remainder of his life.

Lytton Strachey

Lytton Strachey (1880–1932), biographer, reviewer and a quintessential literary figure of the Bloomsbury Group. He is best known for his debunking portraits of Cardinal Manning, Florence Nightingale, Dr. Arnold and General Gordon, published together as Eminent Victorians (London: Chatto & Windus, 1918; Russell’s library), which BR read in Brixton with great amusement as well as some critical reservations (see Letter 7). Although Strachey was homosexual, he and the artist Dora Carrington were devoted to each other and from 1917 lived together in Tidmarsh, Berkshire. BR had become acquainted with the somewhat eccentric Strachey, a fellow Cambridge Apostle, while his slightly younger contemporary was reading history at Trinity College. He admired Strachey’s literary gifts, but doubted his intellectual honesty. Almost three decades later BR fleshed out the unflattering thumbnail of Strachey drawn for Ottoline in Letter 7, in a “Portrait from Memory” for BBC radio. Strachey was “indifferent to historical truth”, BR alleged in that broadcast, “and would always touch up the picture to make the lights and shades more glaring and the folly or wickedness of famous people more obvious” (The Listener 48 [17 July 1952]: 98). Main biography: Michael Holroyd, Lytton Strachey: a Critical Biography, 2 vols. (London: Heinemann, 1967–68).

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

Philip Morrell

Philip Morrell, Ottoline’s husband (1870–1943), whom she had married in 1902 and with whom, four years later, she had twins — Julian, and her brother, Hugh, who died in infancy. The Morrells were wealthy Oxfordshire brewers, although Philip’s father was a solicitor. He won the Oxfordshire seat of Henley for the Liberal Party in 1906 but held this Conservative stronghold only until the next general election, four years later. For the second general election of 1910 he ran successfully for the Liberals in the Lancashire manufacturing town of Burnley. But Morrell’s unpopular anti-war views later cost him the backing of the local Liberal Association, and his failure to regain the party’s nomination for the post-war election of 1918 (see Letter 89) effectively ended his short political career. Unlike many other Liberal critics of British war policy (including BR), Morrell did not transfer his political allegiance to the Labour Party. Although Ottoline and her husband generally tolerated each other’s extra-marital affairs, a family crisis ensued when in 1917 Philip impregnated both his wife’s maid and his secretary (see Letter 48).

Sir Auckland Geddes

Sir Auckland Geddes (1879–1954; 1st Baron Geddes, 1942) was returned unopposed as Conservative M.P. for Basingstoke in a by-election held in October 1917. Before this entry into civilian public life, he held the rank of Brigadier-General as director of recruiting at the War Office. He was an ardent champion of conscription even in peacetime and had a long-standing interest in the military, which he expressed before the war as a volunteer medical officer in the British Army Reserve. He had studied medicine and was Professor of Anatomy at McGill University, Montreal, when the outbreak of war prompted an immediate return to Britain in order to enlist. After a riding accident rendered Geddes unfit for front-line duties, he became a staff officer in France with a remit covering the supply and deployment of troops. He performed similar duties at the War Office until his appointment in August 1917 as a Minister of National Service with broad powers over both military recruitment and civilian labour. Geddes held two more Cabinet positions in Lloyd George’s post-war Coalition Government before his appointment in 1920 as British Ambassador to the United States. After returning from Washington on health grounds three years later, Geddes embarked upon a successful business career, becoming chairman in 1925 of the Rio Tinto mining company. See Oxford DNB.

T.S. Eliot

The poet and critic Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888–1965) was a student of BR’s at Harvard in 1914. BR had sensed his ability, especially “a certain exquisiteness of appreciation” (to Lucy Donnelly, 11 May 1914; SLBR 1: 491), but did not see a genius in embryo. After Eliot travelled to England later the same year, to study philosophy at Oxford under H.H. Joachim, BR became something of a father figure to the younger man. He also befriended Eliot’s (English) wife, Vivienne, whom he had hastily married in 1915 and with whom BR may have had an affair the following year. BR shared his Bloomsbury apartment (at 34 Russell Chambers) with the couple for more than a year after their marriage, and jointly rented a property with them in Marlow, Bucks. (see Letter 78). He further eased Eliot’s monetary concerns by arranging paid reviewing for him and giving him £3,000 in debentures from which BR was reluctant, on pacifist grounds, to collect the income (Auto. 2: 19). Eliot’s financial security was much improved by obtaining a position at Lloyd’s Bank in 1917, but during BR’s imprisonment he faced uncertainty of a different kind as the shadow of conscription loomed over him (see, e.g., Letter 27). Nine years after the war ended Eliot returned the securities (BRACERS 76480).

Telegraph House

Telegraph House, the country home of BR’s brother, Frank. It is located on the South Downs near Petersfield, Hants., and North Marden, W. Sussex. See S. Turcon, “Telegraph House”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 154 (Fall 2016): 45–69.

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).