Brixton Letter 11

BR to Constance Malleson

June 2, 1918

- AL

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-11

BRACERS 19308

<Brixton Prison>1

<early June 1918>2

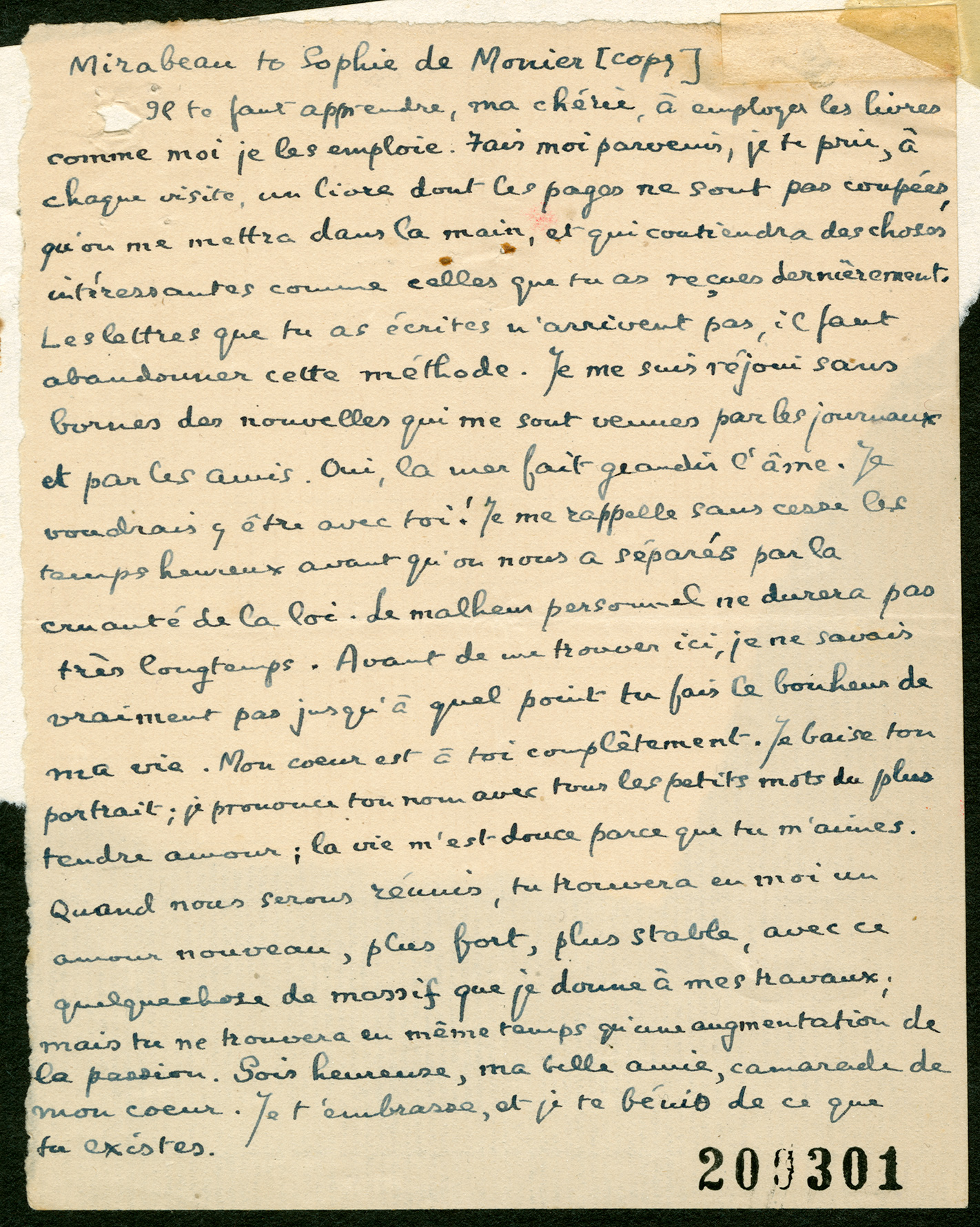

Mirabeau to Sophie de Monier [copy]3

Il te fauta apprendre, ma chérie, à employer les livres comme moi je les emploie.4 Fais moi parvenir, je te prie, à chaque visite, un livre dont les pages ne sont past coupées, qu’on me mettra dans la main, et qui contiendra des choses intéressantes comme celles que tu as reçues dernièrement. <Si> Les lettres que tu as écrites n’arrivent pas, il faut abandonner cette méthode. Je me suis réjoui sans bornes des nouvelles qui me sont venues par les journaux et par les amis. Oui, la mer fait grandir l’âme.5 Je voudrais y être avec toi! Je me rappelle sans cesse les temps heureux avant qu’on nous a séparés par la cruauté de la loi. Le malheur personnel ne durera pas très longtemps. Avant de me trouver ici, je ne savais vraiment pas jusqu’à quel point tu fais le bonheur de ma vie. Mon coeur est à toi complètement. Je baise ton portrait;6 je prononce ton nom avec tous les petits mots du plus tendre amour; la vie m’est douce parce que tu m’aimes. Quand nous serons réunis, tu trouverab en moi un amour nouveau, plus fort, plus stable, avec ce quelquechose de massif que je donne à mes travaux; mais tu ne trouvera en même temps qu’une augmentation de la passion. Sois heureuse, ma belle amie, camarade de mon coeur. Je t’embrasse, et je te bénis de ce que tu existes.

<Translation:>

You need to learn, my dear, how to use books as I use them. I beg you, at each visit, to bring a book in which the pages are not cut, which I shall put in your hand, and which will contain some interesting things like those you’ve received lately. <If> the letters which you have written don’t arrive, it will be necessary to abandon this method. I am happy to receive unlimited news which comes to me from newspapers and friends. Yes, the sea enlarges the soul. I should like to be there with you. I think constantly about the happy times before we were separated by the cruelty of the law. This personal misfortune will not last long. Before finding myself here, I did not really know just how much happiness you brought into my life. My heart belongs to you completely. I kiss your picture; I pronounce your name with all the small words of the most tender love; life is sweet because you love me. When we are together again, you will find in me a new love, stronger, more stable, with something very solid that I give to my work; but you will not find at the same time an increase in passion. Be happy, my love, my heart’s comrade. I hug you, and I bless you for existing.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from BR’s unsigned, handwritten original in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. He filled a quarter-sheet (torn from a full sheet) of ruled paper in a very tiny script and folded it once horizontally.

- 2

[date] In BR’s letter to Frank of 3 June 1918 (Letter 12), he noted in a message to Rinder that he had written something in French for Colette (as Percy) and that it was inside the International Journal. The present letter may be what BR was referring to; hence the date of early June. Rinder replied in a letter sent by Frank and Elizabeth of 6 June 1918 (BRACERS 46918) that she had sent the International Journal but was sorry it was unsuccessful. It must then be supposed that the present letter turned up later. At any rate, it must be contemporaneous with the start of concealing letters in books and journals.

- 3

Mirabeau to Sophie de Monier [copy] Comte de Mirabeau (1749–1791), French revolutionary statesman. Sophie de Monier (sic) was the name he used for Marie Thérèse Sophie Richard de Ruffey, Marquise de Monnier (1754–1789), during their illicit affair. His letters to Sophie when he was imprisoned in the castle at Vincennes were first published in 1793. What follows is actually a love letter from BR to Colette, which also gives her instructions on how to smuggle letters in and out of prison. Later on BR began reading the original correspondence (Letter 43). In this note at the head of Colette’s typed copy of Letter 11, Colette herself explained BR’s temporary reliance on the French language: “At first, to prevent any chance of discovery, the letters were written in the form of <French> quotations.”

- 4

Il te faut apprendre … à employer les livres comme moi je les emploie. Colette had been writing to BR surreptitiously, as “G.J.”, through The Times Personals (see, e.g., note 17 to Letter 2). In addition, messages from “G.J.” and “Percy” had been placed in “official” letters received by BR from Frank and Elizabeth and Gladys Rinder. These messages may have been extracted from entire letters from Colette (e.g. BRACERS 113134), which she later confusingly designated as “official” in order to distinguish them from her later, smuggled correspondence to BR. Although she later made typescripts of what she later called “official” letters, BR would have seen them in Brixton only as messages from “G.J.” or “Percy”. Colette kept open the channels of communication to BR through his brother, sister-in-law and Rinder for a few more weeks, and the last Times Personal from “G.J.” did not appear until 27 June 1918. Both of Colette’s methods of reaching BR — along with his ruse of writing letters to her in French disguised as historical documents — were superseded by their adoption of the subterfuge recommended here. Her earliest smuggled letter to BR is probably that dated 24 June 1918 (BRACERS 113135), while he wrote to her illicitly in English for the first time on 11 June (Letter 17). Ottoline was already delivering contraband correspondence to BR, once concealing a letter, that of 28–30 May, folded many times (BRACERS 114745) in a tiny bunch of flowers (see R. Gathorne-Hardy, ed., Ottoline at Garsington: Memoirs of Lady Ottoline Morrell, 1915–1918 [London: Faber and Faber, 1974], p. 252).

- 5

Oui, la mer fait grandir l’âme. The sea’s function of “enlarging” the soul is in keeping with BR's ethic of impersonal self-enlargement (see K. Blackwell, The Spinozistic Ethics of Bertrand Russell [London: Allen & Unwin, 1985]). Colette wrote about the sea in her letter of 4 June (BRACERS 113134). However, that letter is not an original, so the date is not verifiable. She also wrote about the sea in a message (as G.J.) contained in Frank’s letter of 6 June (BRACERS 46918).

- 6

ton portrait The photograph of Colette taken for BR in 1916 by E.O. Hoppé (1878–1972); it can be viewed above the transcription of each of his prison letters to her.

Textual Notes

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.

Elizabeth Russell

Elizabeth Russell, born Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941), was a novelist who in 1891 married Graf von Arnim-Schlagenthin. She became known as “Elizabeth”, the name she used in publishing Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898), and she remained widely known as Elizabeth von Arnim, although the Library of Congress catalogues her as Mary Annette (Beauchamp), Countess von Arnim. She was a widow when she married BR’s brother, Frank, on 11 February 1916. The marriage was quickly in difficulty; she left it for good in March 1919, but they were never divorced and she remained Countess Russell (becoming Dowager Countess after Frank’s death in 1931).

Frank Russell

John Francis (“Frank”) Stanley Russell (1865–1931; 2nd Earl Russell from 1878), BR’s older brother. Author of Lay Sermons (1902), Divorce (1912), and My Life and Adventures (1923). BR remembered Frank bullying him as a child and as having the character and appearance of a Stanley, but also as giving him his first geometry lessons (Auto. 1: 26, 36). He was accomplished in many fields: sailor, electrician, house builder, pioneer motorist, local politician, lawyer, businessman and company director, and (later) constructive junior member of the second Labour Government. Frank was married three times. The first marriage involved serious legal actions by and against his wife and her mother, but a previous scandal, which ended his career at Oxford, had an overshadowing effect on his life (see Ruth Derham, “‘A Very Improper Friend’: the Influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell”, Russell 37 [2017]: 271–87). The second marriage was to Mollie Sommerville (see Ian Watson, “Mollie, Countess Russell”, Russell 23 [2003]: 65–8). The third was to Elizabeth, Countess von Arnim. Despite difficulties with him, BR declared from prison: “No prisoner can ever have had such a helpful brother” (Letter 20).

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Heart’s Comrade

Colette first called BR her “heart’s comrade” in her letter of 17 November 1916 (BRACERS 112964). On 9 December (BRACERS 112977), she explained: “I want you as comrade as well as lover.” On 9 April 1917 (BRACERS 19145), he reciprocated the sentiment for the first time. In a letter of 1 January 1918 (BRACERS 19260), BR was so upset with her that he could no longer call her “heart’s comrade”. After their relationship was patched up, he wrote on 16 February 1918 (BRACERS 19290): “I do really feel you now again my Heart’s Comrade.” The last time that BR expressed the sentiment in a letter to her was 26 August 1921 (BRACERS 19742).

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.