Brixton Letter 105

BR to Edith Russell

September 15, 1961

- ALS

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila TurconCite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/

brixton-letter-105

BRACERS 20274

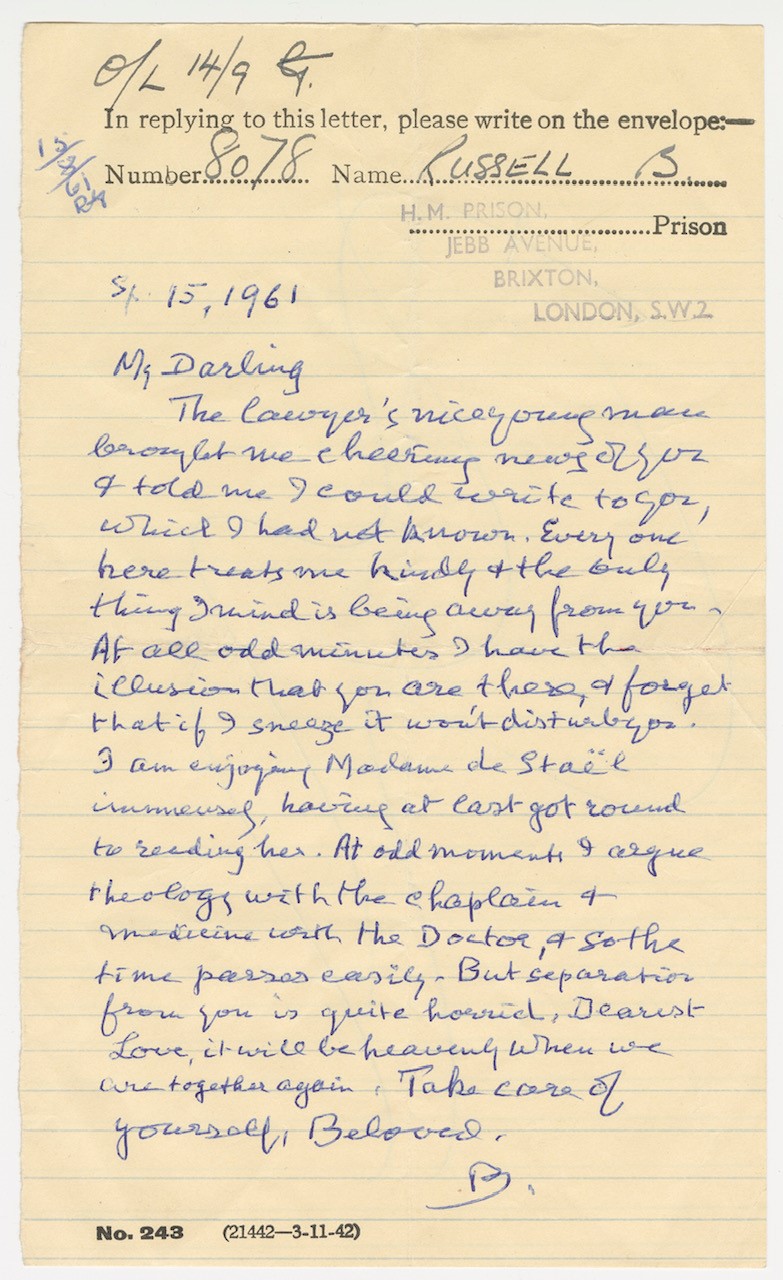

<letterhead>1

Number 8078 Name Russell B.

H.M. PRISON2

JEBB AVENUE,

BRIXTON,

LONDON, S.W.2

Sp 15, 1961

The lawyer’s nice young man4 brought me cheering news of you and told me I could write to you, which I had not known. Every one here treats me kindly and the only thing I mind is being away from you. At all odd minutes I have the illusion that you are there, and forget that if I sneeze it won’t disturb you. I am enjoying Madame de Staël immensely, having at last got round to reading her.5 At odd moments I argue theology with the chaplain6 and medicine with the Doctor,7 and so the time passes easily. But separation from you is quite horrid, Dearest Love, it will be heavenly when we are together again.8 Take care of yourself, Beloved.

B.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from a photocopy in the Russell Archives of the initialled, single-sheet original in BR’s hand. The whereabouts of the original is unknown. There are apparent prison markings, possibly of approval, at the head of the letter: “O/L 14/9 G.”

- 2

H.M. PRISON In September 1961 BR served a second, much shorter sentence in Brixton. As in 1918, his confinement was a direct result of his peace advocacy, which intensified after he became founding president in October 1960 of the Committee of 100, a small anti-nuclear group that favoured civil disobedience. Capping months of protest in which BR was heavily involved (see Auto. 3: 111–18), the Committee of 100 was pushing for a meeting in Trafalgar Square on 17 September, to be followed by a sit-down action in nearby Parliament Square. These demonstrations were to take place at a perilous juncture of the Cold War, with the Berlin Wall having been raised in August 1961 and both superpowers poised to resume nuclear testing. Although permission to gather had been withheld from the organizers (see “Trafalgar Square Meeting”, BR’s letter to The Times, 22 Aug. 1961, p. 9), planning for the events continued apace. As a result, 50 members of the Committee of 100 were summonsed under the medieval Justices of the Peace Act (1361), for inciting breaches of the peace. When 37 defendants, including BR and Edith, appeared before Judge Bertram Reece at Bow St. magistrates’ court on 12 September, all but five refused to be bound over with sureties of good behaviour. The presiding magistrate then handed down 27 prison sentences of one month and four of two months (“Prison for 32 Anti-Nuclear Supporters”, The Times, 13 Sept. 1961, p. 5). BR received one of the longer sentences, but after medical evidence was presented to the court his term was reduced to one week, which he served in Brixton from 12 to 18 September. The same sentence was passed on Edith Russell, who was imprisoned in Holloway. In debating legal strategy three days before these proceedings, the Committee of 100 had considered appealing their anticipated convictions, for publicity purposes, but decided against this because they were “a body calling for civil disobedience and … an appeal through the courts against conviction for so doing would be confusing” (mimeograph minutes, RA2 760.101631). (As it turned out, BR’s initial sentencing alone garnered worldwide attention.) The London demonstration that the authorities wanted to forestall occurred anyway, attracted “unprecedented numbers” (Auto. 3: 117), and resulted in over 1,300 arrests. Since the crowd was prevented from marching down Whitehall to Parliament Square, the sit-down was staged in Trafalgar Square instead (see “1,314 Arrests in Trafalgar Square Disorders”, The Times, 18 Sept. 1961, p. 10).

- 3

DarlingEdith’s only prison letter to BR is dated three days earlier (BRACERS 120273).

- 4

lawyer’s … young man He was likely the Mr. Holland mentioned in Edith’s prison letter (BRACERS 120273) and in BR’s letter of 26 September 1961 to H.S. Pigott of Coward, Chance & Co. (BRACERS 116495). BR thanked Pigott and Holland for the trouble taken “to diminish the discomforts of prison”.

- 5

de Staël Russell’s library has J. Christopher Herold’s Mistress to an Age: a Life of Madame de Staël (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1959). BR told this publisher on 23 September 1961, a few days after his release, that he had “read the life of Mme de Staël in prison where it proved very consoling” (BRACERS 127424). Anne Louise Germaine de Staël-Holstein (1766–1817) was a vocal critic of Napoleon’s authoritarianism and was forced into exile during his rule. Continuing his interest in the French Revolution and its aftermath, BR had already referred favourably to her in “The Superior Virtue of the Oppressed” (1937; 35 in Papers 21).

- 6

chaplain Unidentified.

- 7

Doctor Possibly Francis H. Brisby, who was principal medical officer at Brixton in 1958 (three years before BR’s second imprisonment there) and a vice-president of the Medico-Legal Society until 1966.

- 8

together again BR and Edith were reunited on 18 September after serving their sentences of one week (Monk 2: 420; SLBR 2: 547; Clark, Life, p. 591). There is a same-day photo of them in in their London garden. Another appeared in the London Evening News that day.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Edith Russell

Edith Russell (1900–1978) was an American biographer and part-time academic at Bryn Mawr College with whom BR became acquainted through his American friend Lucy Donnelly. She was the author of Wilfred Scawen Blunt (1938) and Carey Thomas of Bryn Mawr (1947). The former Edith Bronson Finch became BR’s fourth wife in 1952. She was a director of the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation.

French Revolution Reading

In Letter 2 (6 May 1918) BR instructed his brother to ask Evelyn Whitehead to “recommend books (especially memoirs) on French Revolution”, and reported that he was already reading “Aulard” — presumably Alphonse Aulard’s Histoire politique de la révolution française (Paris: A. Colin, 1901). In a message to Ottoline sent via Frank ten days later (Letter 5), BR hinted that he was especially interested in the period after August 1792, which he felt was “very like the present day”. On 27 May (Letter 9), he conveyed to Frank his disappointment that Evelyn had not yet procured for him any memoirs of the revolutionary era, and that Eva Kyle had only furnished him with The Principal Speeches of the Statesmen and Orators of the French Revolution, 1789–1795, ed. H. Morse Stephens, 2 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1892). This was “not the sort of book I want, BR complained”, but “an old stager history which I have read before” (in Feb. 1902: “What Shall I Read?”, Papers 1: 365). Fortunately, some of the desired literature reached him shortly afterwards, including The Private Memoirs of Madame Roland, ed. Edward Gilpin Johnson (London: Grant Richards, 1901: see Letter 12) — or else a different edition of the doomed Girondin’s prison writings — and the Memoirs of the Comtesse de Boigne, ed. Charles Nicoullaud, 3 vols. (London: Heinemann, 1907: see Letter 15). In Letter 48, BR told Ottoline that he was “absorbed in a 3-volume Mémoire” of the Comte de Mirabeau. The edition has not been identified, but quotations attributed to the same aristocratic revolutionary in Letter 44 appear in Lettres d’amour de Mirabeau, précédées d’une étude sur Mirabeau par Mario Proth (Paris: Garnier Frères, 1874). Some weeks after writing Letter 11 to Colette as one purportedly from Mirabeau to Sophie de Monier (sic), BR actually read the lovers’ prison correspondence, possibly in Benjamin Gastineau’s edition: Les Amours de Mirabeau et de Sophie de Monnier, suivis des lettres choisies de Mirabeau à Sophie, de lettres inédites de Sophie, et du testament de Mirabeau par Jules Janin (Paris: Chez tous les libraires, 1865). BR’s reading on the French Revolution also included letters from Études révolutionnaires, ed. James Guillaume, 2 vols. (Paris: Stock, 1908–09), the collection he misleadingly cited as the source for two other illicit communications to Colette (Letters 8 and 10). Also of relevance (Letter 57) were Napoleon Bonaparte’s letters to his first wife, Joséphine de Beauharnais, which BR may have read in this well-known English translation edited by Henry Foljambe Hall: Letters to Josephine, 1796–1812 (London: J.M. Dent, 1901). Finally, BR obtained a hostile, cross-channel perspective on the French Revolution and Napoleon from Lord Granville’s Private Correspondence, 1781–1821, ed. Castalia, Countess Granville, 2 vols. (London: J. Murray, 1917: see Letters 40, 41 and 44). Commenting towards the end of his sentence on the mental freedom that he had been able to preserve in Brixton, BR wrote about living “in the French Revolution” among other times and places (Letter 90). His immersion in this tumultuous era may have been deeper still if he perused other works not mentioned in his Brixton letters — which he may well have done. Yet BR’s examination of the French Revolution was not at all programmatic (as intimated perhaps by his preference for personal accounts (diaries and letters in addition to memoirs) — unlike much of his philosophical prison reading. Although his political writings are scattered with allusions to the French Revolution (in which he was interested long before Brixton), BR never produced a major study of it. Just over a year after his imprisonment, however, he did publish a scathing and even profound review of reactionary author Nesta H. Webster’s history of the French Revolution, which certainly drew on his reservoir of knowledge about the period (“The Seamy Side of Revolution”, The Athenaeum, no. 4,665 [26 Sept. 1919]: 943–4; Papers 15: 19). While imprisoned briefly in Brixton for a second time, in September 1961, Russell returned to the era of the French Revolution and Napoleon, “enjoying … immensely” (Letter 105) this biography of Mme. de Staël: J. Christopher Herold, Mistress to an Age: a Life of Madame de Staël (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1959; Russell’s library).

Edith Russell

Edith Russell (1900–1978) was an American biographer and part-time academic at Bryn Mawr College with whom BR became acquainted through his American friend Lucy Donnelly. She was the author of Wilfred Scawen Blunt (1938) and Carey Thomas of Bryn Mawr (1947). The former Edith Bronson Finch became BR’s fourth wife in 1952. She was a director of the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation.