Brixton Letter 102

BR to Ottoline Morrell

September 11, 1918

- ALS

- Texas

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-102

BRACERS 18692

<Brixton Prison>1

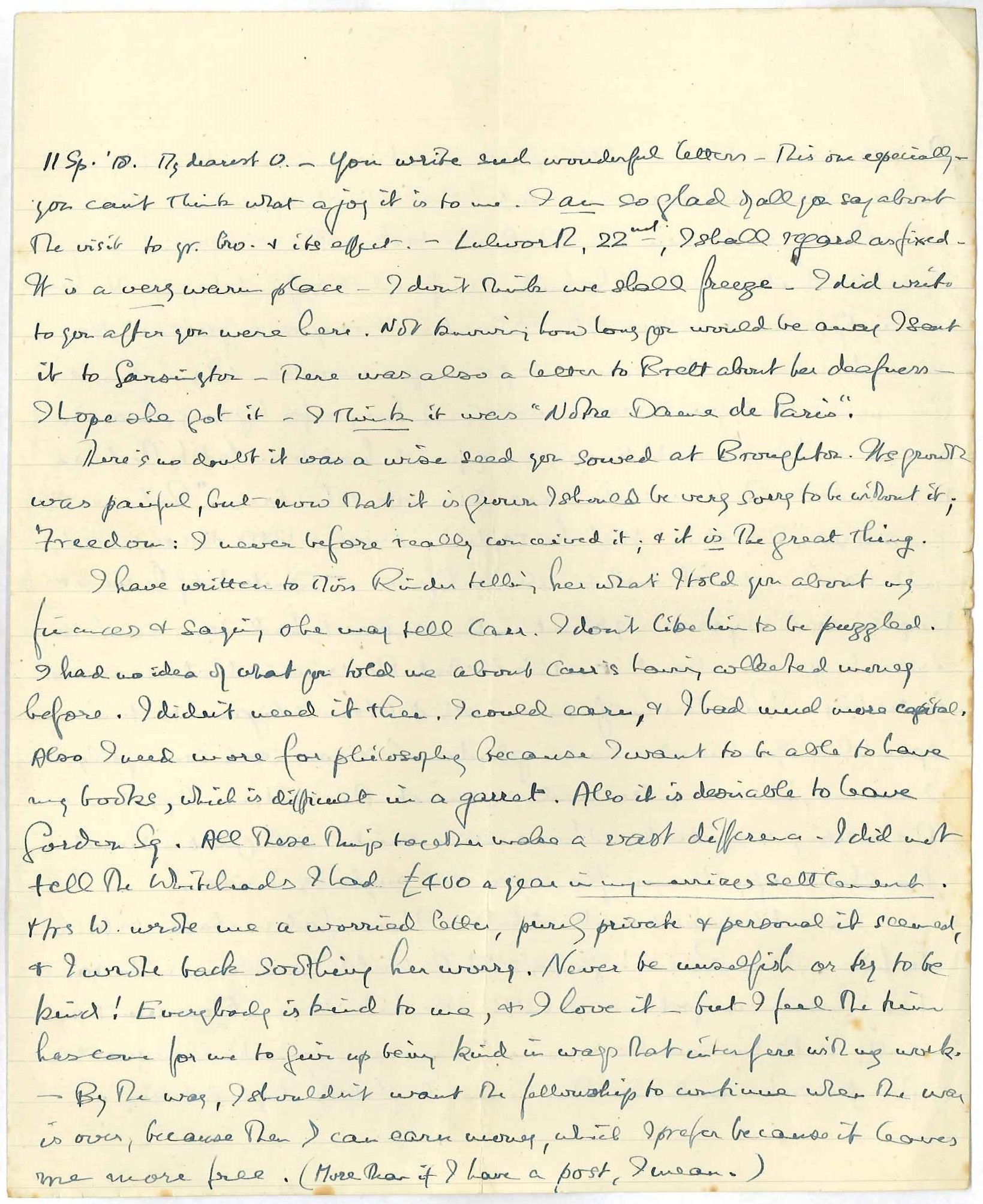

11 Sp. ’18.

My dearest O.

You write such wonderful letters — this one especially2 — you can’t think what a joy it is to me. I am so glad of all you say about the visit to your brother3 and its effect. — Lulworth, 22nd, I shall regard as fixed.4 It is a very warm place — I don’t think we shall freeze. I did write to you after you were here.5 Not knowing how long you would be away I sent it to Garsington — there was also a letter to Brett about her deafness — I hope she got it.6 I think it was Notre Dame de Paris.7

There’s no doubt it was a wise seed you sowed at Broughton.8 Its growth was painful, but now that it is grown I should be very sorry to be without it; Freedom: I never before really conceived it; and it is the great thing.

I have written to Miss Rinder9 telling her what I told you about my finances and saying she may tell Carr. I don’t like him to be puzzled. I had no idea of what you told me about Carr’s having collected money before.10 I didn’t need it then. I could earn, and I had much more capital.11 Also I need more for philosophy because I want to be able to have my books, which is difficult in a garret. Also it is desirable to leave Gordon Sq. All these things together make a vast difference. I did not tell the Whiteheads I had £400 a year in my marriage settlement.12 Mrs W. wrote me a worried letter, purely private and personal it seemed, and I wrote back soothing her worry.13 Never be unselfish or try to be kind! Everybody is kind to me, and I love it — but I feel the time has come for me to give up being kind in ways that interfere with my work. — By the way, I shouldn’t want the fellowship to continue when the war is over, because then I can earn money, which I prefer because it leaves me more free. (More than if I have a post, I mean.)

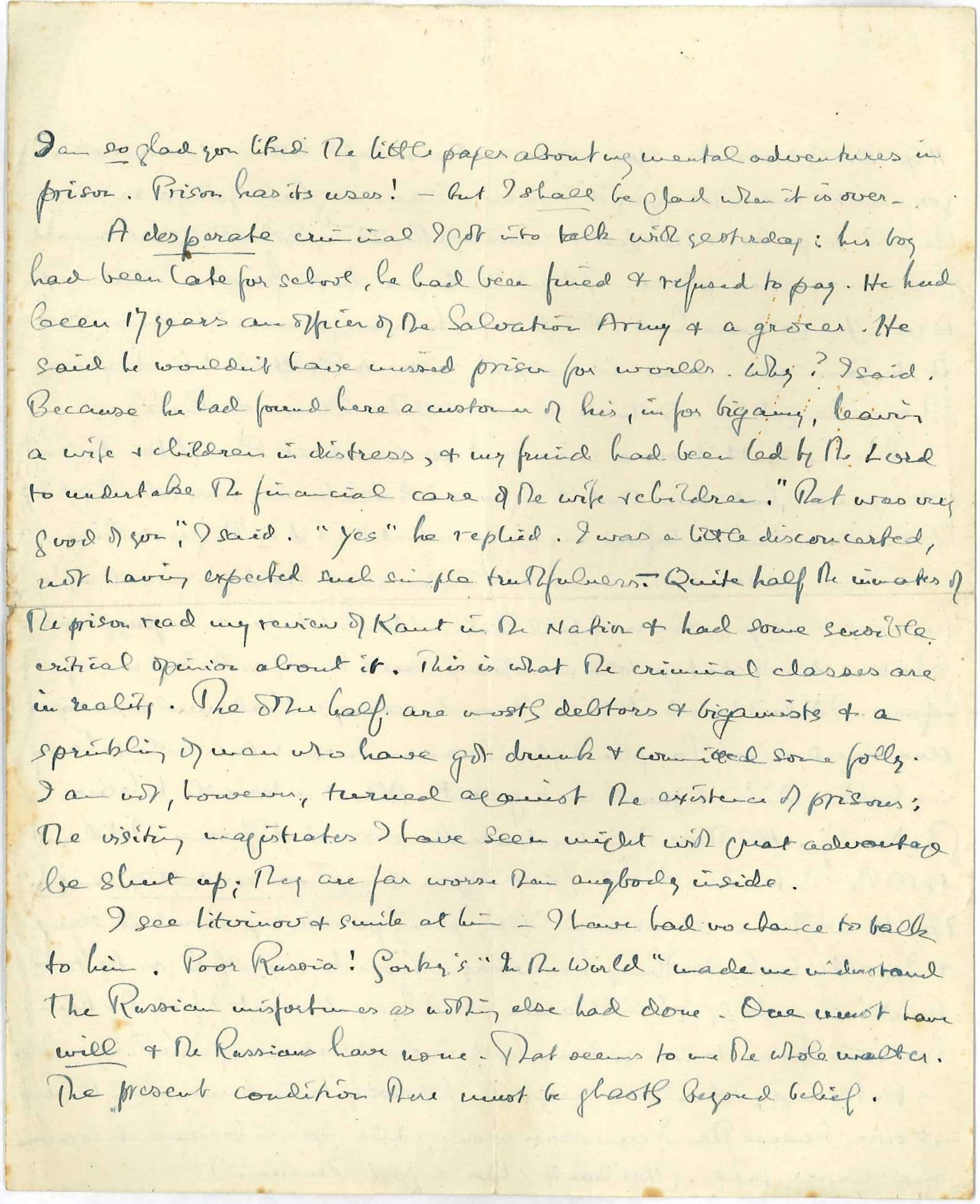

I am so glad you liked the little paper about my mental adventures in prison.14 Prison has its uses! — but I shall be glad when it is over.

A desperate criminal15 I got into talk with yesterday: his boy had been late for school, he had been fined and refused to pay. He had been 17 years an officer of the Salvation Army and a grocer. He said he wouldn’t have missed prison for worlds. Why? I said. Because he had found here a customer of his, in for bigamy, leaving a wife and children in distress, and my friend had been led by the Lord to undertake the financial care of the wife and children. “That was very good of you”, I said. “Yes” he replied. I was a little disconcerted, not having expected such simple truthfulness. — Quite half the inmates of the prison read my review of Kant in the Nation16 and had some sensible critical opinion about it. This is what the criminal classes are in reality. The other half are mostly debtors and bigamists and a sprinkling of men who have got drunk and committed some folly. I am not, however, turned against the existence of prisons: the visiting magistrates17 I have seen might with great advantage be shut up; they are far worse than anybody inside.

I see Litvinov and smile at him18 — I have had no chance to talk to him. Poor Russia! Gorky’s In the World19 made me understand the Russian misfortunes as nothing else had done. One must have will and the Russians have none. That seems to me the whole matter. The present condition there20 must be ghastly beyond belief.

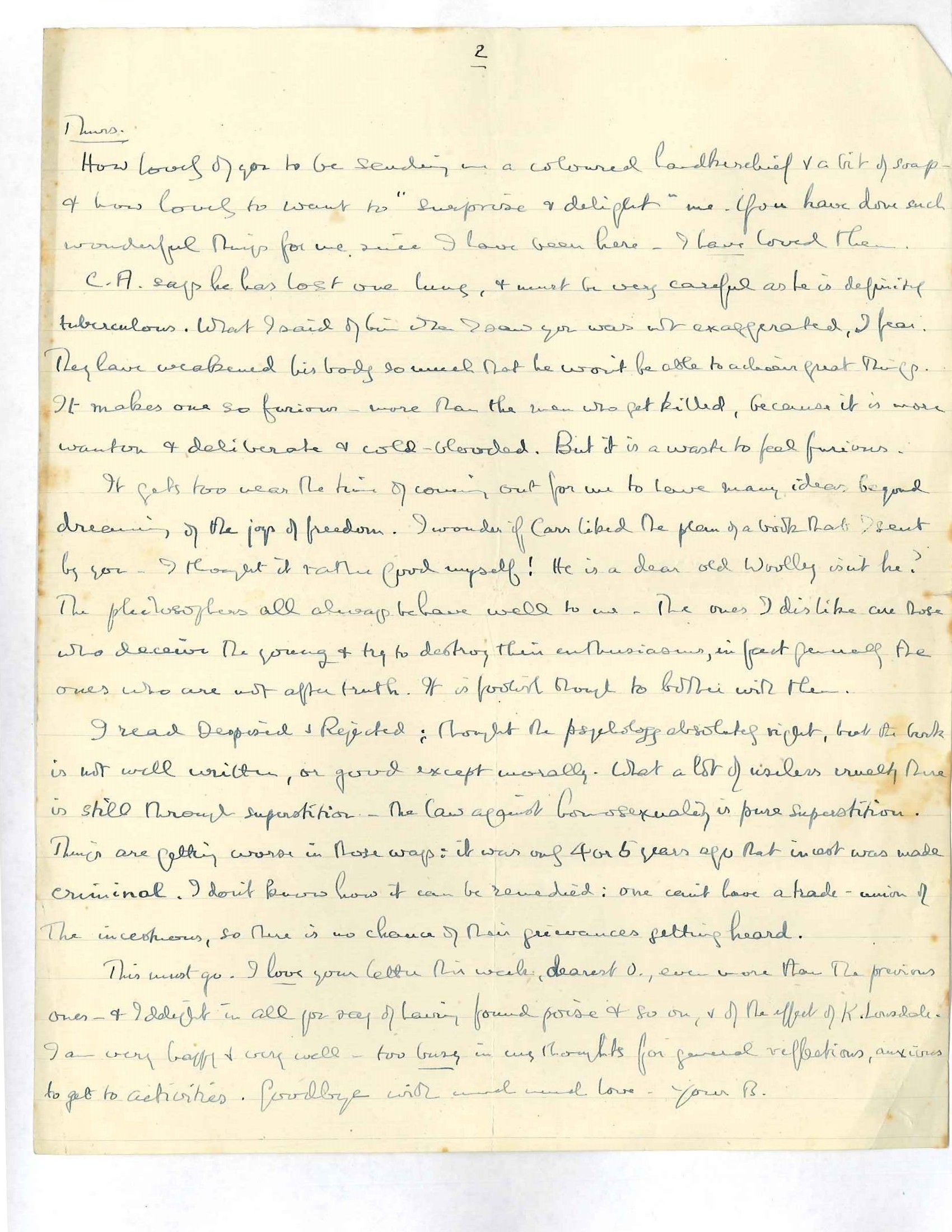

Thurs.

How lovely of you to be sending me a coloured handkerchief and a bit of soap21 — and how lovely to want to “surprise and delight” me. You have done such wonderful things for me since I have been here. I have loved them.

C.A. says he has lost one lung, and must be very careful as he is definitely tuberculous. What I said of him when I saw you was not exaggerated, I fear. They have weakened his body so much that he won’t be able to achieve great things. It makes one so furious — more than the men who get killed, because it is more wanton and deliberate and cold-blooded. But it is a waste to feel furious.

It gets too near the time of coming out for me to have many ideas beyond dreaming of the joys of freedom. I wonder if Carr liked the plan of a book22 that I sent by you. I thought it rather good myself! He is a dear old Woolley23 isn’t he? The philosophers all always behave well to me. The ones I dislike are those who deceive the young and try to destroy their enthusiasms, in fact generally the ones who are not after truth. It is foolish though to bother with them.

I read Despised and Rejected;24 thought the psychology absolutely right, but the book is not well written, or good except morally. What a lot of useless cruelty there is still through superstition — the law against homosexuality25 is pure superstition. Things are getting worse in those ways: it was only 4 or 5 years ago that incest was made criminal.26 I don’t know how it can be remedied: one can’t have a trade-union of the incestuous, so there is no chance of their grievances getting heard.

This must go. I love your letter this week,27 dearest O., even more than the previous ones — and I delight in all you say of having found poise and so on, and of the effect of K. Lonsdale.28 I am very happy and very well — too busy in my thoughts for general reflections, anxious to get to activities. Goodbye with much much love.

Your

B.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from digital scans of the initialled original in BR’s hand in the Morrell papers at the University of Texas at Austin. The first sheet was folded three times; the second sheet, twice, with the verso blank except for “Lady Ottoline” written on both exposed quarter-sheets. The second sheet, whose text begins “Thurs. | How lovely of you”, was scanned with the original of Letter 70, but belongs with the present letter, for in it BR was anxious to hear of Carr’s reception of the book outline that BR sent via Ottoline (see note 22 below). Moreover, Ottoline’s week in Kirkby Lonsdale did not begin until 29 August (see note 3 below).

- 2

letters — this one especially Undated, the letter to which BR replied here is at BRACERS 114758.

- 3

visit to your brother Ottoline spent the week of 29 August to 4 September 1918 at Underley Hall, just outside Kirkby Lonsdale in the Lake District, where her brother Henry Cavendish-Bentinck (1863–1931), Conservative M.P., lived in the country house inherited by his wife, Lady Olivia. “I loved being with Henry”, she reported. “He was so dear and so human and full of kindness to Humanity so extraordinarily tender to Humanity — you know really how I love that, perhaps it is soppy of me — but he and I are alike in that and it’s the way one is made” (BRACERS 114758). Ottoline had four brothers and one half-brother. BR had met Henry, her favourite, in 1911 (Miranda Seymour, Ottoline Morrell: Life on a Grand Scale [London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1992], pp. 150–1). Henry shared with a handful of other Conservative politicians (Lord Hugh Cecil and Lord Parmoor most notably) serious qualms about the harsh and illiberal treatment of C.O.s.

- 4

Lulworth, 22nd, I shall regard as fixed Keenly anticipating this visit to the Dorset coast in late October, BR told Ottoline after his release that he was “counting on Lulworth” (3 Oct. 1918, BRACERS 18698). Despite BR’s assumption that the arrangements were settled, Ottoline dropped out of the planned trip on 7 October (BRACERS 114761), and BR ended up going to Lulworth with Colette instead, on 16–19 October.

- 5

I did write to you after you were here Probably it was Letter 89, which Ottoline did not receive.

- 6

letter to Brett about her deafness … hope she got itLetter 88 to Bloomsbury artist Dorothy Brett, who had suffered dramatic, progressive hearing-loss after undergoing surgery for appendicitis in 1902. She did not receive this letter.

- 7

I think it was Notre Dame de Paris BR’s letter to Brett was smuggled out of Brixton in a copy of this Gothic novel by Victor Hugo, first published in 1831, or another book loaned to him by the Trevelyans (see Letter 88).

- 8

it was a wise seed you sowed at BroughtonOttoline had remembered the conversation in a Broughton churchyard of which BR reminded her in his letter of 4 September (Letter 94). Regarding the moral “wildness” that she had pressed upon BR in August 1912, Ottoline queried whether she had sown “a wise seed”, before answering, “Yes. Devil Take it. It must be — growth is essential even if it means passing through Fire” (9–10 Sept. 1918, BRACERS 114758). BR wholeheartedly agreed with this assessment of a defining moment in his emotional life, having already told her (four years previously) that “what you said entered into the depths of me and has dominated all my thought ever since” (22 Feb. 1914, BRACERS 18140).

- 9

I have written to Miss Rinder The letter about BR’s finances is not extant in the Russell Archives.

- 10

Carr’s having collected money before When on 6 September Ottoline travelled with Gladys Rinder to discuss the fellowship plan with Wildon Carr at his West Sussex home, he disclosed that he had once already raised a subscription for BR from among academic philosophers. But Carr returned the funds after being convinced by the Whiteheads that BR’s finances were much less parlous than Carr had assumed. According to Ottoline, this occurred “some months ago” (BRACERS 114758), probably before BR’s trial. BR readily conceded that he had been more financially secure then, but that Carr was mistaken in thinking that BR’s marriage settlement (see below) alone was worth £400 “clear” per annum. Carr drew this incorrect inference after being shown BR’s “soothing” letter to Evelyn Whitehead (see below). His misunderstanding did have some bearing on the fellowship plan, Ottoline related in the same letter, because after his prior fundraising experience, Carr “naturally now doesn’t feel inclined to start off asking again.” In explaining BR’s finances to Carr, Rinder presumably mentioned, inter alia, the capital he had gifted to T.S. Eliot. This may not have reassured Carr, who, Ottoline suspected, “thinks you play ducks and drakes with your money and give it away to Causes and if he gave you more — it would go the same way.” That Carr had reservations about the financial aspect of the proposed action on BR’s behalf does not mean, however, that he was anything less than fully supportive of it — merely that, as Rinder noted, “he won’t be responsible for collection of money for Fellowship” (6 Sept. 1918, BRACERS 79633).

- 11

I had much more capital The disbursements from BR’s capital since 1917 are unknown, but they may have included the gift of £3,000 in debentures to T.S. Eliot (Auto. 2: 19) and large legal expenses.

- 12

my marriage settlement The historic purpose of such legal agreements was to afford married women a measure of financial security of which they were deprived by the common-law doctrine of couverture. Until the late-Victorian era, wives enjoyed no legal standing separate from their husbands’ and could not hold property in their own right. A typical marriage settlement placed all or part of a bride’s dowry assets in trust. The practice persisted among the well-to-do even after the Married Women’s Property Act became law in 1882, and it was not unusual for the groom’s family to contribute to a settlement as well, and for both husband and wife to be beneficiaries — as appears to have been the case with BR and Alys, for BR had his own settlement trust. A list of the financial securities tied to BR’s marriage settlement (compiled shortly after his divorce from Alys in September 1921) shows assets of approximately £10,000 (see BRACERS 80113). The income generated by the settlement three years previously cannot be ascertained precisely, for some of the investments were held in stocks. Moreover, in indicating to Rinder that this amount was less than £400 net, BR was probably taking into account the charitable dispersal of his unearned income — which was considerable (see note 13 below) and included, several years earlier, gifts totalling several thousand pounds to the Whiteheads. The most definite information about the marriage settlement in 1918 is that the interest on a £3,600 mortgage owned by BR had increased from 4% to 5½% (see BRACERS 80113). This promised to yield an additional £54 per annum, for a sum of almost £200 gross produced from just one source of income in the marriage settlement. BR would have deducted income tax and life insurance to get net income (see Letter 12).

- 13

I wrote back soothing her worry In the only surviving letter from BR to Evelyn Whitehead (27 July 1917, BRACERS 119038), he had tried to assuage her concern that he was struggling financially: “I still have £400 a year clear apart from what I earn. I was very hard up for a time, because I had got into the way of giving away what I don’t earn, and I couldn’t stop suddenly — I had counted on Trinity and America to keep me going and both failed simultaneously. But I succeeded in letting my flat (it is still let), and soon I found new ways of earning money, more than before — by writing and lecturing. The result is that I am better off than I was while I was at Trinity”. Clearly he did not limit the account of his income to that from his marriage settlement.

- 14

little paper about my mental adventures in prison I.e., Letter 90, 31 August 1918, which begins: “There never was such a place for crowding images”. Ottoline referred to it in the postscript to her previous letter (BRACERS 114757).

- 15

A desperate criminal He is described in BR’s “Are Criminals Worse Than Other People?” (New York American, 29 Oct. 1931, p. 15; in Mortals and Others [London: Routledge, 2009], p. 30).

- 16

my review of Kant in the Nation “Pure Reason at Königsberg”, a largely favourable assessment of Norman Kemp Smith, A Commentary to Kant’s “Critique of Pure Reason” (London: Macmillan, 1918), in The Nation 23 (20 July 1918): 426, 428; 14 in Papers 8. He concluded the review thus: “It is with a strange heartache that one looks back to the days when the Königsberg philosopher lived a life of pure reason; in our time the life of reason is more difficult and more painful.” BR almost never failed to allude, in some way, to his own situation in what he wrote in prison for publication under his own name.

- 17

magistrates BR had written in Roads to Freedom: “People who take a rosy view of human nature might have supposed that the duties of a magistrate would be among disagreeable trades, like cleaning sewers; but a cynic might contend that the pleasures of vindictiveness and moral superiority are so great that there is no difficulty in finding well-to-do elderly gentlemen who are willing, without pay, to send helpless wretches to the torture of prison” (London: Allen & Unwin, 1918, p. 112).

- 18

I see Litvinov and smile at him Early in 1918 Maxim Litvinov (1876–1951), a future Soviet foreign minister, obtained de facto recognition as Bolshevik Russia’s diplomatic representative to Britain. He and his staff were interned in Brixton for several weeks in retaliation for the arrest of Robert Bruce Lockhart, his London counterpart in Moscow, who stood accused with other British agents of conspiring to sabotage the revolution (Britain had that summer launched a military intervention against the fledgling Bolshevik regime.) But a prisoner exchange was hastily negotiated and both men were soon released and repatriated. BR and Litvinov would have acknowledged each other because they had previously met on at least three separate occasions (see Papers 14: lxxix–lxxx).

- 19

Gorky’s In the World Translated by Gertrude M. Foakes (London: T. Werner Laurie, 1918), this was the second volume of autobiography by Russian revolutionary and writer Maxim Gorky (1868–1936). It chronicled the grim and drab reality of the Russian lives encountered by Gorky as a runaway orphan wandering and working across the Tsarist Empire. While visiting Russia with a British Labour Delegation in May 1920, BR had a short audience with an ailing Gorky in Petrograd. He found him “the most lovable, and to me the most sympathetic, of all the Russians I saw” (The Practice and Theory of Bolshevism [London: Allen & Unwin, 1920], p. 43).

- 20

The present condition there Famine had gripped not only the Bolshevik heartland of Russia but also the more peripheral zones contested or controlled by Allied-backed White Russians fighting to overthrow Lenin’s regime. Shortages of fuel and consumer goods, disrupted transportation networks, and collapsing urban infrastructure only added to the woes of the Russian people during this phase of the civil war. In the spring of 1918 a raft of statist economic measures was introduced to revive industry and ease the supply of food to the towns. In the short term, however, this policy of “war communism” only exacerbated the problem of rural hoarding and brought class war to the countryside with a vengeance as peasant farmers resisted the forced requisitioning (see Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy: the Russian Revolution, 1891–1924 [London: Cape, 1996], pp. 603–22).

- 21

a coloured handkerchief and a bit of soap Ottoline referred to her intention to send these in her letter of 25–27 August 1918 (BRACERS 114756).

- 22

if Carr liked the plan of a book The “plan and outline” which had been sent to the philosopher H. Wildon Carr seem to be the manuscript titled “Bertrand Russell’s Notes on the New Work Which He Intends to Undertake” (RA 210.006570; typed carbon, 210.006571; the carbon, which alone is titled, is printed in Papers 8: App. II). The piece is incorrectly dated there “the first months of 1918”. It was instead the fruit of some months of research in Brixton, and the manuscript has the prison governor’s initials, “CH”. The verso of folio 3 of the manuscript was annotated by BR: “Words, Thoughts and Things. [To be given to Wildon Carr, and shown to any one whom it may interest.]” There is a further note by BR, in pencil: “Carr per Miss Rinder, Thursday”. The manuscript begins: “If circumstances permit, the following is the work upon which I shall be engaged in the immediate future: Plan for a work on ‘Things, Words, and Thoughts’, being the section dealing with cognition in a large projected work, Analysis of Mind.” Rinder told BR in her letter of 5–6 September 1918 (BRACERS 79632) that “Dr. Carr has your notes for your projected work. Don’t understand your reference to typescript for D.W. <Dorothy Wrinch.> Does it refer to a typed copy of these notes?” It surely did so refer. It is safe to assume that this plan of BR’s projected work, written between the morning Letter 69 to Colette and the evening Letter 70 to Ottoline on 14 August 1918, was the one that Carr had in September.

- 23

Woolley “Wildon Carr the philosopher, whom Elizabeth called the woolly Lamb.” (BR’s note at BRACERS 119473.)

- 24

Despised and Rejected The main character in this novel by Austrian-born British author Rose Laure Allatini (1890–1980) (writing as A.T. Fitzroy) was a homosexual composer and a C.O. imprisoned for refusing to enlist. Allatini was certainly courting controversy by tackling the themes of homosexuality and pacifism. In October 1918 the publisher of Despised and Rejected (London: C.W. Daniel, 1918) was prosecuted under the Defence of the Realm Act, fined £100 with £10 costs and ordered to surrender his stock of the proscribed book (“‘Despised and Rejected’”, The Times, 11 Oct. 1918, p. 5).

- 25

law against homosexuality The Criminal Law Amendment Act (1885) reinforced the legal prohibition of male homosexuality by proscribing all sexual acts between men (but not women) as offences of gross indecency punishable by two years’ imprisonment with hard labour. Convictions on such charges were much easier to secure than for the separate and more serious felony offence of sodomy, which had first been outlawed by a Tudor statute, remained a capital crime until 1861, and carried the possibility of a life sentence thereafter. As intimated to Ottoline, BR was vigorously opposed to Britain’s criminalization of homosexuality, which in Marriage and Morals (London: Allen & Unwin, 1929) he blamed on “a barbarous and ignorant superstition, in favour of which no rational argument of any sort or kind can be advanced” (p. 90). In the 1950s he joined the Homosexual Law Reform Society to help liberalize and ultimately repeal the law on homosexuality.

- 26

Things are getting worse … 4 or 5 years ago … incest was made criminal Until passage of the Punishment of Incest Bill in 1908, sexual relations between siblings, or parents and children or grandchildren, were not offences under the criminal law. These sexual relations had been prohibited hitherto only by English canon law — following the stern biblical injunction against incest in Leviticus 18: 6 — under which, however, penance was the sole punitive sanction. Evidently BR was far from reassured by the more stringent disciplinary powers (of imprisonment for up to seven years) conferred upon the State ten years previously (not “4 or 5 years ago”). His opposition to this measure was partly grounded in a deep-seated and lasting mistrust of all such legislative proscriptions (see, e.g., his notes for “Morals in Legislation”, a 1954 speech about obscenity law, which also mention his brother’s objections to the 1908 Act [Papers 28: 459]). Although BR certainly appreciated the social importance of the incest taboo (see New Hopes for a Changing World [London: Allen & Unwin, 1951], pp. 60–1), he also considered its power disproportionate to the harm inflicted in some cases. He illustrated this point by reference to a novel he had first read in Brixton more than thirty years beforehand (see Letter 100): “Defoe’s Moll Flanders is far from exemplary, and commits many crimes without a qualm; but when she finds that she has inadvertently married her brother she is appalled, and can no longer endure him as a husband although they had lived happily together for years. This is fiction, but it is certainly true to life” (Human Society in Ethics and Politics [London: Allen & Unwin, 1954], p. 30).

- 27

your letter this week See note 2 above.

- 28

K. Lonsdale “Her brother Lord Henry Cavendish Bentinck lived at Kirkby Lonsdale.” (BR’s note at BRACERS 119473.)

57 Gordon Square

The London home of BR’s brother, Frank, 57 Gordon Square is in Bloomsbury. BR lived there, when he was in London, from August 1916 to April 1918, with the exception of January and part of February 1917.

Annotations by BR

In the late 1940s, when BR was going through his archives, and in the 1950s when he was revising his Autobiography, he would occasionally annotate letters. He did this to sixteen of the Brixton letters. Links to them are gathered here for convenient access to these new texts. In the annotations to the letters they are always followed by “(BR’s note.)”

Letter 2, note 5 happy.

5, note 6 congratulations to G.J.

9, note 28 bit of Girondin history.

12, note 6 friend.

15, note 2 (the letter in general).

20, note 7 G.J.

31, note 3 Dr’s treatment.

40, notes 9, 10 Ld. G.L.G, Lady B’s.

44, note 14 S.S.

48, note 48 Mother Julian’s Bird.

57, notes 13, 16 Ld. Granville’s to Ly. B., bless that Dr. … seat of intellect.

70, note 15 Mrs Scott.

73, note 12 E.S.P. Haynes.

76, note 4 Cave.

85, note 2 Marsh on Rupert.

102, notes 23, 28 Woolley, K. Lonsdale.

General Annotations

Brett note from Auto. 2: 93

Cousens note from Auto. 2: 71

Kyle note with her letters to BR

Rinder note from Auto. 2: 88n.

Silcox note on BRACERS 80365

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Clifford Allen

(Reginald) Clifford Allen (1889–1939; Baron Allen of Hurtwood, 1932) was a socialist politician and publicist who joined the Cambridge University Fabian Society while studying at Peterhouse College (1908–11). After graduating he became active in the Independent Labour Party in London and helped establish a short-lived labour newspaper, the Daily Citizen. During the war Allen was an inspiring and effective leader of the C.O. movement as chairman of the No-Conscription Fellowship, which he co-founded with Fenner Brockway in November 1914. Court-martialled and imprisoned three times after his claim for absolute exemption from war service was rejected, Allen became desperately ill during his last spell of incarceration. He was finally released from the second division of Winchester Prison on health grounds in December 1917, but not before contracting the tuberculosis with which he was finally diagnosed in September 1918. He was dogged by ill health for the rest of his life. BR had enormous affection and admiration for Allen (e.g., 68 in Papers 13, 46 in Papers 14), a trusted wartime political associate. From February 1919 until March 1920 he even shared Allen’s Battersea apartment. A close friendship was soured, however, by Allen’s rejection of BR’s unforgiving critique of the Bolshevik regime, which both men witnessed at first hand with the British Labour Delegation to Russia in May 1920 (see Papers 15: 507). Yet Allen was far from revolutionary himself and did not even identify with the left wing of the ILP (which he chaired in the early 1920s). He was elevated to the peerage as a supporter of Ramsay MacDonald’s National Government, an administration despised by virtually the entire labour movement. Although Allen’s old intimacy with BR was never restored after the Russia trip, any lingering estrangement did not inhibit him from enrolling his daughter, Joan Colette (“Polly”) at the Russells’ Beacon Hill School.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.

Dorothy Brett

Dorothy Eugénie Brett (1883–1977), painter, benefitted from the patronage of Ottoline Morrell, who set up a studio for her at Garsington Manor. She lived there for three years (1916–19), becoming friends with J. Middleton Murry and Katherine Mansfield, among other visitors to the Morrells’ country home. Brett was the daughter of Liberal politician and courtier Viscount Esher. Notwithstanding her generous encouragement of Brett’s work, Ottoline could become impatient with her guest’s acute deafness, about which BR wrote compassionately in Letter 88. BR’s note below that letter in Auto. 2: 93 reads: “The lady to whom the above letter is addressed was a daughter of Lord Esher but was known to all her friends by her family name of Brett. At the time when I wrote the above letter, she was spending most of her time at Garsington with the Morrells. She went later to New Mexico in the wake of D.H. Lawrence.”

Dorothy Wrinch

Dorothy Maud Wrinch (1894–1976), mathematician, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. She studied mathematics and philosophy at Girton College, Cambridge, and came under BR’s influence in her second year when she took his course on mathematical logic. She taught mathematics at University College, London, 1918–21, and then at Oxford, 1922–30. Her first publications were in mathematical logic and philosophy, and during the 1920s she wrote on the philosophy of science. But in the 1930s her interests turned to mathematical biology and crystallography, and in 1935 she moved to the United States on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship and remained there for the rest of her life. Unfortunately, as a biologist she is best known for a long and stubborn controversy with Linus Pauling about the structure of proteins in which he was right and she was wrong. See Marjorie Senechal, I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science (New York: Oxford U. P., 2013). Chapter 7 is devoted to Wrinch’s interactions with BR in Brixton.

Elizabeth Russell

Elizabeth Russell, born Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941), was a novelist who in 1891 married Graf von Arnim-Schlagenthin. She became known as “Elizabeth”, the name she used in publishing Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898), and she remained widely known as Elizabeth von Arnim, although the Library of Congress catalogues her as Mary Annette (Beauchamp), Countess von Arnim. She was a widow when she married BR’s brother, Frank, on 11 February 1916. The marriage was quickly in difficulty; she left it for good in March 1919, but they were never divorced and she remained Countess Russell (becoming Dowager Countess after Frank’s death in 1931).

Evelyn Whitehead

Evelyn (Willoughby-Wade) Whitehead (1865–1961). Educated in a French convent, she married Alfred North Whitehead in 1891. Her suffering, during an apparent angina attack, inspired BR’s profound sympathy and occasioned a storied episode which he described as a “mystic illumination” (Auto. 1: 146). Through her he supported the Whitehead family finances during the writing of Principia Mathematica. During the early stages of his affair with Ottoline Morrell, she was BR’s confidante. They maintained their mutual affection during the war, despite the loss of her airman son, Eric. BR last visited Evelyn in 1950 in Cambridge, Mass., when he found her in very poor health.

Fellowship Plan

Since the upper-age limit for compulsory military service had been increased to 50 in April 1918, BR was faced with the unnerving prospect of being conscripted after his release from Brixton. Early in his imprisonment he was already wondering about his “position when I emerge from here” (Letter 9). While his conviction was still under appeal, he had broached with Clifford Allen and Gilbert Murray the possibility of avoiding military service, not by asserting his conscientious objection to it, but by obtaining accreditation of his philosophical research as work of national importance (see note to Letter 24). The Pelham Committee, set up by the Board of Trade in March 1916, was responsible for the designation of essential occupations and recommending to the local tribunals, who adjudicated claims for exemption from military service, that C.O.s be considered for such positions. BR reasoned to Murray on 2 April that a dispensation to practise philosophy (as opposed to working outside his profession), would enable to him to “avoid prison without compromise” — i.e., of his political and moral opposition to conscription (BRACERS 52367). Although BR intended to withdraw from political work, he told Murray two days later, he would not promise to abstain from peace campaigning (BRACERS 52369). It should be noted that C.O.s who accepted alternative service in special Home Office camps were expressly prohibited from engaging in pacifist activities (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 231).

BR was far from sanguine about the prospect of success before a local tribunal. But he came to think (by early June) that his chances would be improved if his academic supporters interceded directly with the Minister of National Service, Sir Auckland Geddes. In addition, he calculated that such entreaties would be more effective if those acting on his behalf could secure and even endow a fellowship for him and thereby have “something definite to put before Geddes” (Letter 12; see also Letters 15 and 19). BR definitely wanted to rededicate himself to philosophy and would have welcomed a new source of income from academic employment (see Letter 22). But the “financial aspect was quite secondary”, he reminded Frank on 24 June (Letter 27); he was interested in the fellowship plan primarily as a safeguard against being called up, for teachers over 45 were not subject to the provisions of the recently amended Military Service Act. In the same letter, however, BR told his brother that “I wish it <the plan> dropped” on account of reservations expressed to him in person by Wildon Carr and A.N. Whitehead (see also Letter 31), two philosophers whom he respected but who seemed to doubt whether BR’s financial needs were as great as they appeared (see note to Letter 102).

Yet BR’s retreat was only temporary. On 8 August, he expressed to Ottoline a renewed interest in the initiative, and a few days later, she, her husband and Gladys Rinder met in London to discuss the matter. As Ottoline reported to BR, “we all felt that it was useless to wait for others to start and we decided that P. and I should go and see Gilbert M. and try and get him to work it with the Philosophers” (11 Aug. 1918, BRACERS 114754). BR probably wanted Murray to spearhead this lobbying (see also Letters 65 and 70) because of his political respectability and prior success in persuading professional philosophers to back an appeal to the Home Secretary for BR’s sentence to be served in the first division (see Letter 6). Murray did play a leading role but not until early the following month, when BR was anxious for the fellowship plan to succeed as his release date neared. The scheme finally gathered momentum after a meeting between Ottoline, Rinder and Carr on 6 September 1918, at which the philosopher and educationist T. Percy Nunn, another academic supporter of BR, was also present. Within a few days Murray had drafted a statement with an appeal for funds, which was endorsed by Carr, Whitehead, Nunn, Samuel Alexander, Bernard Bosanquet, G. Dawes Hicks, A.E. Taylor and James Ward. This memorial was then circulated in confidence to philosophers and others, but only after BR’s release from Brixton. (Financial pledges had already been made by a few of BR’s friends and admirers, notably Lucy Silcox and Siegfried Sassoon.) BR’s solicitor, J.J. Withers, became treasurer of this endowment fund, the goal of which was to provide BR with £150 or £200 per annum over three years. On 30 August BR had confessed to Ottoline that he did not want an academic position “very far from London” (Letter 89) and reiterated this desire in a message to Murray communicated by Rinder (Letter 97). On 6 September Rinder (BRACERS 79633) hinted that she already knew where the appointment would be, but there are no other indications that a particular establishment had been decided upon. Ultimately, no affiliation was contemplated for BR, so the memorial stated, because “in the present state of public feeling no ordinary university institution is likely to be willing to employ him as a teacher” (copy in BRACERS 56750). The circular talked instead of a “special Lectureship”, and the £100 BR received from the fund early in 1919 was explicitly issued as payment for lectures (on “The Analysis of Mind”; see syllabus, in Papers 9: App. III.1) that he would deliver that spring. BR’s solicitor also informed him that provision existed to pay him a further £100 for an autumn lecture course (see syllabus, ibid.: App. III.2), and Withers anticipated that these arrangements might “last two or three years” (2 Jan. 1919, BRACERS 81764). BR had already obtained a £50 gift from the fund in November 1918. Somewhat ironically, the critical importance of a teaching component to the fellowship plan — as insurance against conscription — was reduced by the authorities hesitating to hound BR any further after his imprisonment, and all but nullified by the end of the war a few weeks later. (There were no fresh call-ups, but the last of the C.O.s already in prison were not released until August 1919, and conscription remained in effect until April 1920.)

Gladys Rinder

W. Gladys Rinder worked for the No-Conscription Fellowship and was “chiefly concerned with details in the treatment of pacifist prisoners” (BR’s note, Auto. 2: 88). More specifically, she helped administer the Conscientious Objectors’ Information Bureau, a joint advisory committee set up in May 1916 and representing two other anti-conscription organizations — the Friends’ Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation — as well as the NCF. One C.O. later testified to her “able and zealous” management of this repository of records on individual C.O.s (see John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience: a History, 1916–1919 [London: Allen & Unwin, 1922], p. 186). Rinder exhibited similar qualities in assisting with the distribution of BR’s correspondence from prison and in writing him official and smuggled letters. Her role in the NCF changed in June 1918, and after the Armistice she assumed control of a new department dedicated to campaigning for the immediate release of all imprisoned C.O.s. She appears to have lost touch with BR after the war but continued her peace advocacy, which included publishing occasionally on international affairs. In 1924 she travelled to Washington, DC, as part of the British delegation to a congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Decades later Colette remembered Rinder to Kenneth Blackwell as somebody who “seemed about 40 in 1916–18. She was a completely nondescript person, but efficient, and kind” (BRACERS 121687).

Governor of Brixton Prison / Carleton Haynes

Captain Carleton Haynes (1858–1945), the Governor of Brixton Prison in 1918, was a retired army officer and a cousin of BR’s acquaintance, the radical lawyer and author E.S.P. Haynes. In March 1919 BR sent Haynes, in jest, a copy (now in the Russell Archives) of his newly published Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy — so that the governor’s collection of works written by inmates while under his charge would “not ... be incomplete” (BRACERS 123167).

H. Wildon Carr

Herbert Wildon Carr (1857–1931), Professor of Philosophy at King’s College, London, from 1918 and Visiting Professor at the University of Southern California from 1925. Carr came to philosophy late in life after a lucrative career as a stockbroker. His philosophy was an idiosyncratic amalgam of Bergsonian vitalism and Leibnizian monadology, which, he thought, was supported by modern biology and the theory of relativity. He wrote books on Bergson and Leibniz at opposite ends of his philosophical career and a book on relativity in the middle. His philosophy would have made him an unlikely ally of BR’s, but it was Carr who organized BR’s two courses of public lectures, on philosophy of mathematics and the philosophy of logical atomism, which brought BR back to philosophy and improved his finances in 1917–18. Carr had great administrative talents, which he employed also on behalf of the Aristotelian Society during his long association with it. He was its president in 1916–18 and continued to edit its Proceedings until 1929.

Russell Chambers

34 Russell Chambers, Bury Street (since renamed Bury Place), London WC1, BR’s flat since 1911. Helen Dudley rented the flat in late 1916 or early 1917. In May 1918 she sublet it to Clare Annesley. Colette moved in on 9 September 1918 and stayed until June 1919. BR did not give up the lease until December 1923. See S. Turcon, “Russell Chambers, Other London Flats, and Country Homes, 1911–1923”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 150 (Fall 2014): 30–4. “Russell Chambers, Other London Flats, and Country Homes, 1911–1923”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin, no. 150 (Fall 2014): 30–4.

T.S. Eliot

The poet and critic Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888–1965) was a student of BR’s at Harvard in 1914. BR had sensed his ability, especially “a certain exquisiteness of appreciation” (to Lucy Donnelly, 11 May 1914; SLBR 1: 491), but did not see a genius in embryo. After Eliot travelled to England later the same year, to study philosophy at Oxford under H.H. Joachim, BR became something of a father figure to the younger man. He also befriended Eliot’s (English) wife, Vivienne, whom he had hastily married in 1915 and with whom BR may have had an affair the following year. BR shared his Bloomsbury apartment (at 34 Russell Chambers) with the couple for more than a year after their marriage, and jointly rented a property with them in Marlow, Bucks. (see Letter 78). He further eased Eliot’s monetary concerns by arranging paid reviewing for him and giving him £3,000 in debentures from which BR was reluctant, on pacifist grounds, to collect the income (Auto. 2: 19). Eliot’s financial security was much improved by obtaining a position at Lloyd’s Bank in 1917, but during BR’s imprisonment he faced uncertainty of a different kind as the shadow of conscription loomed over him (see, e.g., Letter 27). Nine years after the war ended Eliot returned the securities (BRACERS 76480).

Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Morrell, née Cavendish-Bentinck (1873–1938). Ottoline, who was the half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland and grew up in the politically involved aristocracy, studied at St. Andrews and Oxford. She married, in 1902, Philip Morrell (1870–1943), who became a Liberal M.P. in 1910. She is best known as a Bloomsbury literary and artistic hostess. BR and she had a passionate but non-exclusive love affair from 1911 to 1916. They remained friends for life. She published no books of her own but kept voluminous diaries (now in the British Library) and was an avid photographer of her guests at Garsington Manor, near Oxford. (The photos are published in Lady Ottoline’s Album [1976] and mounted at the website of the National Portrait Gallery.) In the 1930s she had a large selection of BR’s letters to her typed, omitting sensitive passages. BR’s letters to her are with the bulk of her papers at the University of Texas, Austin.