Brixton Letter 10

BR to Constance Malleson

May 27, 1918

- ALS

- McMaster

- Edited by

Kenneth Blackwell

Andrew G. Bone

Nicholas Griffin

Sheila Turcon

Cite The Collected Letters of Bertrand Russell, https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/brixton-letter-10SLBR 2: #315

BRACERS 19310

<Brixton Prison>1

<c.27 May 1918>2

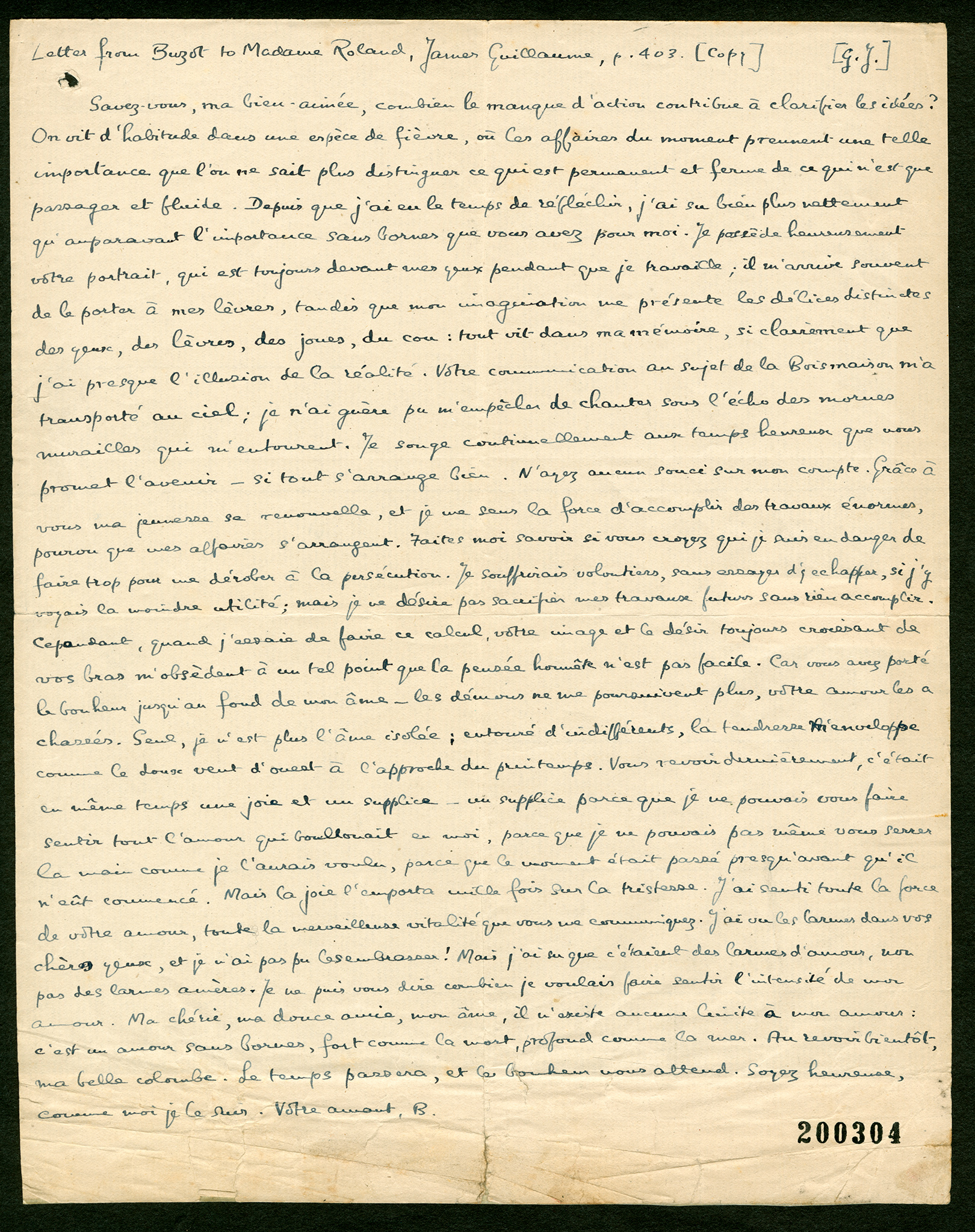

Letter from Buzot to Madame Roland,3 James Guillaume,4 p. 403 [Copy] [G.J.]5

Savez-vous, ma bien-aimée, combien le manque d’action contribue à clarifier les idées? On vit d’habitude dans une espèce de fièvre, où les affaires du moment prennent une telle importance que l’on ne sait plus distinguer ce qui est permanent et ferme de ce qui n’est que passager et fluide. Depuis que j’ai eu le temps de réfléchir, j’ai su bien plus nettement qu’auparavant l’importance sans bornes que vous avez pour moi. Je possède heureusement votre portrait, qui est toujours devant mes yeux pendant que je travaille; il m’arrive souvent de le porter à mes lèvres, tandis que mon imagination me présente les délices distinctes des yeux, des lèvres, des joues, du cou: tout vit dans ma mémoire, si clairement que j’ai presque l’illusion de la réalité. Votre communication au sujet de la Boismaison6 m’a transporté au ciel; je n’ai guère pu m’empêcher de chanter sous l’écho des mornes murailles qui m’entourent. Je songe continuellement aux temps heureux que nous promet l’avenir — si tout s’arrange bien. N’ayez aucun souci sur mon compte. Grâce à vous ma jeunesse se renouvelle, et je me sens la force d’accomplir des travaux énormes, pouroua que mes affaires s’arrangent. Faites moi savoir si vous croyez qui je suis en danger de faire trop pour me dérober à la persécution. Je souffrirais volontiers, sans essayer d’y echapper, si j’y voyais la moindre utilité; mais je ne désire pas sacrifier mes travaux futurs sans rien accomplir. Cependant, quand j’essaie de faire ce calcul, votre image et le désir toujours croissant de vos bras m’obsèdent à un tel point que la pensée honnête n’est pas facile. Car vous avez porté le bonheur jusqu’au fond de mon âme — les démons ne me poursuivent plus, votre amour les a chassés. Seul, je n’est plusb l’âme isolée; entouré d’indifférents, la tendresse m’enveloppe comme le doux vent d’ouest à l’approche du printemps. Vous revoir dernièrement, c’était en même temps une joie et un supplice — un supplice parce que je ne pouvais vous faire sentir tout l’amour qui bouillonnaitc en moi, parce que je ne pouvais pas même vous serrer la main comme je l’aurais voulu, parce que le moment était passé presqu’avant qu’il n’eût commencé. Mais la joie l’emporta mille fois sur la tristesse. J’ai senti toute la force de votre amour, toute la merveilleuse vitalité que vous me communiquez. J’ai vu les larmes dans vos chèrs yeux, et je n’ai pas pu les embrasser! Mais j’ai su que c’étaient des larmes d’amour, non pas des larmes amères. Je ne puis vous dire combien je voulais faire sentir l’intensité de mon amour. Ma chérie, ma douce amie, mon âme, il n’existe aucune limite à mon amour: c’est un amour sans bornes, fort comme la mort, profond comme la mer. Au revoir bientôt,d ma belle colombe. Le temps passera, et le bonheur vous attend. Soyez heureuse, comme moi je le suis.

Votre amant,

B.

<Translation:>

Do you know, my beloved, how much the lack of action contributes to clarifying ideas? Usually we live in a type of fever, in which the events of the moment take on such an importance that we no longer know how to distinguish what is permanent and fixed from what is only passing and fluid. Since I’ve had the time to reflect, I know more clearly than before the unlimited importance that you have for me. Fortunately I have your picture, which is always before my eyes while I work; I often bring it to my lips, while my imagination conjures up for me the individual delights of your eyes, your lips, your cheeks, your neck: everything lives in my memory, so clearly that I almost have the illusion of reality. Your message on the subject of Boismaison transported me to heaven; I could hardly stop myself from singing under the echo of the dull walls that surround me. I dream continuously of the happy times that are promised us in the future — if all goes well. Have no worry on my account. Thanks to you my youth has been renewed, and I feel strong enough to accomplish enormous tasks, provided that my affairs go well. Let me know if you think that I am in danger of doing too much to escape persecution. I should willingly suffer, without trying to escape from it, if I saw any use in it; but I don’t desire to sacrifice my future work without accomplishing anything. However, when I try to do this calculation, your image and the ever-growing desire for your arms obsesses me so much that honest thought isn’t easy. Because you bring happiness to the bottom of my soul — the demons no longer pursue me, your love has chased them away. Alone, I am no longer an isolated soul; surrounded by indifference, tenderness envelops me like the soft westerly wind at the approach of spring. Seeing you again last time was both a joy and a torment — a torment because I can’t make you feel all the love that seethes in me, because I can’t even take your hand as I should have liked, because the moment had passed almost before it had started. But happiness lifts me a thousand times higher than sadness. I felt all the strength of your love, all the marvellous vitality that you bring to me. I saw the tears in your dear eyes, and I couldn’t kiss them! But I knew they were the tears of love, not bitter tears. I can’t tell you how much I want you to feel the intensity of my love. My dear, my sweet love, my soul, there exists no limit to my love: it’s a love without boundaries, strong as death, profound as the sea. Goodbye, my beautiful dove. The time will pass, and happiness awaits you. Be happy, as I am.

Your lover

B.

- 1

[document] The letter was edited from the initialled original in BR’s handwriting in the Malleson papers in the Russell Archives. BR filled one side of a ruled sheet and folded it twice. The letter was published as #315 in Vol. 2 of BR’s Selected Letters.

- 2

[date] The date is taken from Colette’s message published in The Times Personals, 27 May 1918 (BRACERS 96082).

- 3

Buzot to Madame Roland François Nicolas Léonard Buzot (1760–1794), a far-left Girondin deputy in the French National Assembly. His love affair with Madame Roland started in 1792, a few months before she was arrested and he had to flee for his life. They smuggled letters to each other while she was in jail and he in hiding. He committed suicide to avoid arrest six months after she was executed.

- 4

James Guillaume James Guillaume (1844–1916) was a French historian (and a translator and anthologizer of Bakunin: see Letter 61). BR had evidently been reading his Études révolutionnaires (2 vols., 1908–09), which include a number of letters from the French Revolution although none by Buzot.

- 5

[Copy] [G.J.] “Copy” was part of the ruse of pretending to copy passages from a book. “G.J.” was one of Colette’s aliases.

- 6

Votre communication … de la BoismaisonColette’s message (as G.J.) appeared in The Times Personals, 27 May 1918: “G.J. — Your letter has made my whole world radiant, only living until Boismaison. Longing and longing for that. Please, please write again” (BRACERS 96082).

Textual Notes

Boismaison

Colette and BR vacationed at a house, The Avenue, owned by Mrs. Agnes Woodhouse and her husband, in the countryside near Ashford Carbonel, Shropshire, in August 1917. They nicknamed the house “Boismaison”. Agnes Woodhouse took in paying guests. Their first visit was idyllic. They returned for other vacations — in 1918 before he entered prison and in April 1919. Their plan to go soon after he got out of prison failed because their relationship faltered for a time. They discussed returning in the summer of 1919 — a booking was even made for 12–19 July — but in the end they didn’t go. See S. Turcon, “Then and Now: Bertie and Colette’s Escapes to the Peak District and Welsh Borderlands”, Russell 34 (2014): 117–30.

Brixton Prison

Located in southwest London Brixton is the capital’s oldest prison. It opened in 1820 as the Surrey House of Correction for minor offenders of both sexes, but became a women-only convict prison in the 1850s. Brixton was a military prison from 1882 until 1898, after which it served as a “local” prison for male offenders sentenced to two years or less, and as London’s main remand centre for those in custody awaiting trial. The prison could hold up to 800 inmates. Originally under local authority jurisdiction, local prisons were transferred to Home Office control in 1878 in an attempt to establish uniform conditions of confinement. These facilities were distinct from “convict” prisons reserved for more serious or repeat offenders sentenced to longer terms of penal servitude.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.

Constance Malleson

Lady Constance Malleson (1895–1975), actress and author, was the daughter of Hugh Annesley, 5th Earl Annesley, and his second wife, Priscilla. “Colette” (as she was known to BR) was raised at the family home, Castlewellan Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland. Becoming an actress was an unusual path for a woman of her class. She studied at Tree’s (later the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), debuting in 1914 with the stage name of Colette O’Niel at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, in a student production. She married fellow actor Miles Malleson (1888–1969) in 1915 because her family would not allow them to live together. In 1916 Colette met BR through the No-Conscription Fellowship and began a love affair with him that lasted until 1920. The affair was rekindled twice, in 1929 and 1948; they remained friends for the rest of his life. She had a great talent for making and keeping friends. Colette acted in London and the provinces. She toured South Africa in 1928–29 and the Middle East, Greece and Italy in 1932 in Lewis Casson and Sybil Thorndike’s company. She acted in two films, both in 1918, Hindle Wakes and The Admirable Crichton, each now lost. With BR’s encouragement she began a writing career, publishing a short story in The English Review in 1919. She published other short stories as well as hundreds of articles and book reviews. Colette wrote two novels — The Coming Back (1933) and Fear in the Heart (1936) — as well as two autobiographies — After Ten Years (1931) and In the North (1946). She was a fierce defender of Finland, where she had lived before the outbreak of World War II. Letters from her appeared in The Times and The Manchester Guardian. Another of her causes was mental health. She died five years after BR in Lavenham, Suffolk, where she spent her final years. See S. Turcon, “A Bibliography of Constance Malleson”, Russell 32 (2012): 175–90.